TF-4: Refuelling Growth: Clean Energy and Green Transitions

Women have been shown to be disproportionately affected by the climate crisis as well as the recent COVID-19 pandemic, yet their role in enhancing climate resiliency, post-pandemic recovery, and socio-economic stability has often been overlooked. This policy brief focusses on the G20’s role in future-proofing law and governance for climate resilience through a human rights-based approach that enhances women’s entrepreneurship. It recommends targeted measures for women entrepreneurs to freely access finance, markets, and networks where their efforts towards climate resilience enhance smart and efficient green transition pathways. The International Monetary Fund expects one-third of the world economy to experience recession in 2023—exacerbating inequality divides. The World Bank notes that the global labour force participation rate for women is just over 50 percent compared to 80 percent for men. With 85 percent of global GDP, 75 percent of global trade, and two-thirds of the world population, the G20’s role in bolstering climate resilience through women’s entrepreneurship is crucial.

1. The Challenge

The G20 Bali Leaders’ Declaration observed that women are disproportionately affected by the COVID-19 pandemic as well as the climate crisis.[1] The need for law and governance to not just be responsive but also proactive in responding to the scientific, socio-economic, and political uncertainties associated with climate crises is key to enhancing climate resiliency. ‘Resilience’ refers to “the ability of a system, community, or society exposed to hazards to resist, absorb, accommodate, adapt to, transform, and recover from the effects of the hazard in a timely and efficient manner, including through the preservation and restoration of its essential structures and functions through risk management.”[2]

Such proactivity makes policy measures ‘futureproof’. A low-carbon, climate resilient economy is the only way to meet development imperatives and ensure progress towards the United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).[3] This policy brief, therefore, will highlight the role the G20 can play in enhancing women’s entrepreneurship, creating smart and efficient green transition pathways and enabling climate resiliency across diverse nations. Empowering women will mean educating families/communities about their socio-economic rights and refuelling growth en route to the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development[4] and beyond, through gender-responsive measures.

In order to achieve the target of limiting global warming to 1.5°C, as outlined in the Paris Agreement,[5] a 45 percent reduction in emissions from their 2010 levels is required by 2030. Additionally, complete carbon neutrality must be attained by 2050.[6] In thirty-three years of international climate negotiations, it has been observed that the governments’ inability to effectively carry out their treaty commitments and the insufficient response of the business sector primarily obstruct climate action and ambition.[7] The G20’s role is crucial in reimagining multilateralism and ensuring nations’ commitment to climate resiliency and net zero goals. This reiterates what the UN Secretary-General António Guterres proposed to the G20—a Climate Solidarity Pact,[8] emphasising the need for international solidarity and support to assist developing countries in transitioning to low-carbon and climate-resilient economies.

At the same time, embedding green transitions ought to encompass societal and behavioural norms, as women play an integral part in families, communities, and other wider spheres of influence. Businesses led by women make significant contributions to the global economy, particularly in developing countries, where Small and Micro Enterprises are estimated to create 70 percent of employment opportunities and generate 40 percent of economic growth.[9] Further, closing the gender gap in entrepreneurship is predicted to potentially boost the global economy by US$5 trillion.[10] However, women entrepreneurs in G20 countries, often face considerable hurdles, like access to capital and labour markets, cultural, regulatory and administrative barriers, gender pay gap, and lack of funding opportunities, to name a few.[11] The challenge remains in addressing the inadequacy of existing governance frameworks and hence, putting forward an enabling policy environment for women entrepreneurs to pursue climate resiliency in societies and nations.

2. The G20’s Role

Women’s economic empowerment remains at the heart of India’s G20 agenda—where, not just women’s development, but women-led development of economies, is prioritised.[12] By looking at a few G20 countries and beyond, one can identify the key opportunities and challenges encountered while enhancing women’s entrepreneurship. India has an increasing number of women-owned enterprises with an estimated 13.5 million to 15.7 million MSMEs (Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises) and agribusinesses.[13] By enhancing female workforce participation in the country and bridging its gender equality gap, India has the potential to boost its Gross Domestic Product by up to 18 percent, equivalent to approximately US$770 billion.[14] Saudi Arabia has showcased progress with respect to women’s participation in the labour market, achieving an increase of 35.6 percent during the second quarter of 2022, surpassing the initial baseline of 17 percent in 2017, and exceeding the targeted rate of 31.4 percent by 2025[15]—as a result of the National Transformation Program.[16]

In Russia, the female labour force was largest in 2010 and smallest in 2021[17]—a decline that has been concerning for women in entrepreneurship. In Germany, according to the German Start-up Monitor, an increase in start-ups founded by women, from 15.1 percent in 2018 to 20.3 percent in 2022, can be observed.[18] In Mexico, female labour force participation is lowest in the Latin America and Caribbean region,[19] and the gender gap remains significantly high,[20] albeit an increase in women entrepreneurs has also been observed.[21] In the United Kingdom, the number of all-women-led companies has risen significantly, with over 150,000 new companies founded in 2022, and 20.5 percent of new incorporations in 2021 being all-female led, up from 16 percent in 2018.[22] Beyond the few G20 countries mentioned above, the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor 2022/2023 Global Report notes that at least one in five women were observed to be involved in starting a new business, in seven countries, with Guatemala and Colombia having the highest levels observed. Conversely, in eight countries, fewer than one in 20 women were engaged in similar entrepreneurial activities. However, the lowest levels of women’s entrepreneurship were found in Poland, Morocco, and Greece.[23]

Across different geographies, the successes and challenges involved in creating a favourable environment for women entrepreneurs can be observed, and although most nations are showing an upward trend, the challenges for women entrepreneurs are still manifold:

- Female-owned businesses are often smaller and grow less rapidly than male-owned businesses.[24] They need more networks and educational/training programs to support their businesses and navigate (developed and emerging) markets.

- Labour market security needs to be monitored in areas where employees with open-ended contracts and temporary contracts are common (e.g., Argentina and the Republic of Korea), and the prevalence of informal employment (e.g., India and Mexico) is rampant.[25]

- Access to capital remains key to enhancing women’s entrepreneurship.[26] Women encounter barriers in accessing business financing, including bank credit and private investment. Studies show that banks are observed to discriminate against women[27] and investors tend to prefer entrepreneurial ventures led by men in comparison to women.[28]

- Gender biases and stereotypes need to be tackled[29] and such myth-busting must be prioritised across sectors.[30]

How can the G20 create viable opportunities to address these challenges:

By mainstreaming human rights (with emphasis on socio-economic rights): While the Global North frames climate change as an issue of reducing greenhouse gas emissions,[31] the Global South primarily frames it as a human rights issue.[32] However, an interconnected collective ambition encompassing both these priorities across the globe, is important. A report by Ian Fry, special rapporteur on the protection of human rights in the context of climate change, states that the G20 members, account for 78 percent of emissions over the last decade.[33] The G20 has the potential to push for greater international solidarity for climate action, while also tackling issues of global food security, water scarcity, and post-pandemic recovery, to name a few of the socio-economic challenges across the globe. The need to, therefore, address all programmes of development co-operation, policies, and technical assistance in such a way that it will further the realisation of human rights standards and norms, as laid down in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights[34] is important. Further, it is crucial to emphasise economic social, and cultural rights, as enshrined in the International Covenant on Economic Social Rights.[35] In such efforts, women’s involvement in ‘greentech’ will enhance green pathways forward.[36] Women entrepreneurs, after all, are more inclined to address social issues through innovation, as compared to their male counterparts. This use of innovation to further social agendas is seen in ‘purpose-driven enterprises’ that challenge the status quo by developing innovative solutions that address crises that communities face.[37] Mainstreaming human rights will give law and governance frameworks of justice, protection, and remedies, where the protection and promotion of rights is prioritised and radical implementation is executed. For instance,

- Ensuring worker welfare—e.g., maternity benefits, zero-tolerance policies for harassment or sexual violence, flexible work arrangements, crèche facilities, equal pay and pay transparency, access to educational opportunities and so on.

- Providing financial inclusion—e.g., access to credit, financial literacy, security and educational programmes, collateral-free loans, access to microfinancing opportunities, policy and regulatory support, government grants and subsidies, opportunities for peer lending and crowd funding, market access and export assistance, to name a few.

Framing policies under a human rights-based approach through the G20 can help implement targeted legal and political measures to sustain and develop women in greentech—where entrepreneurship and innovation meet climate action.[38]

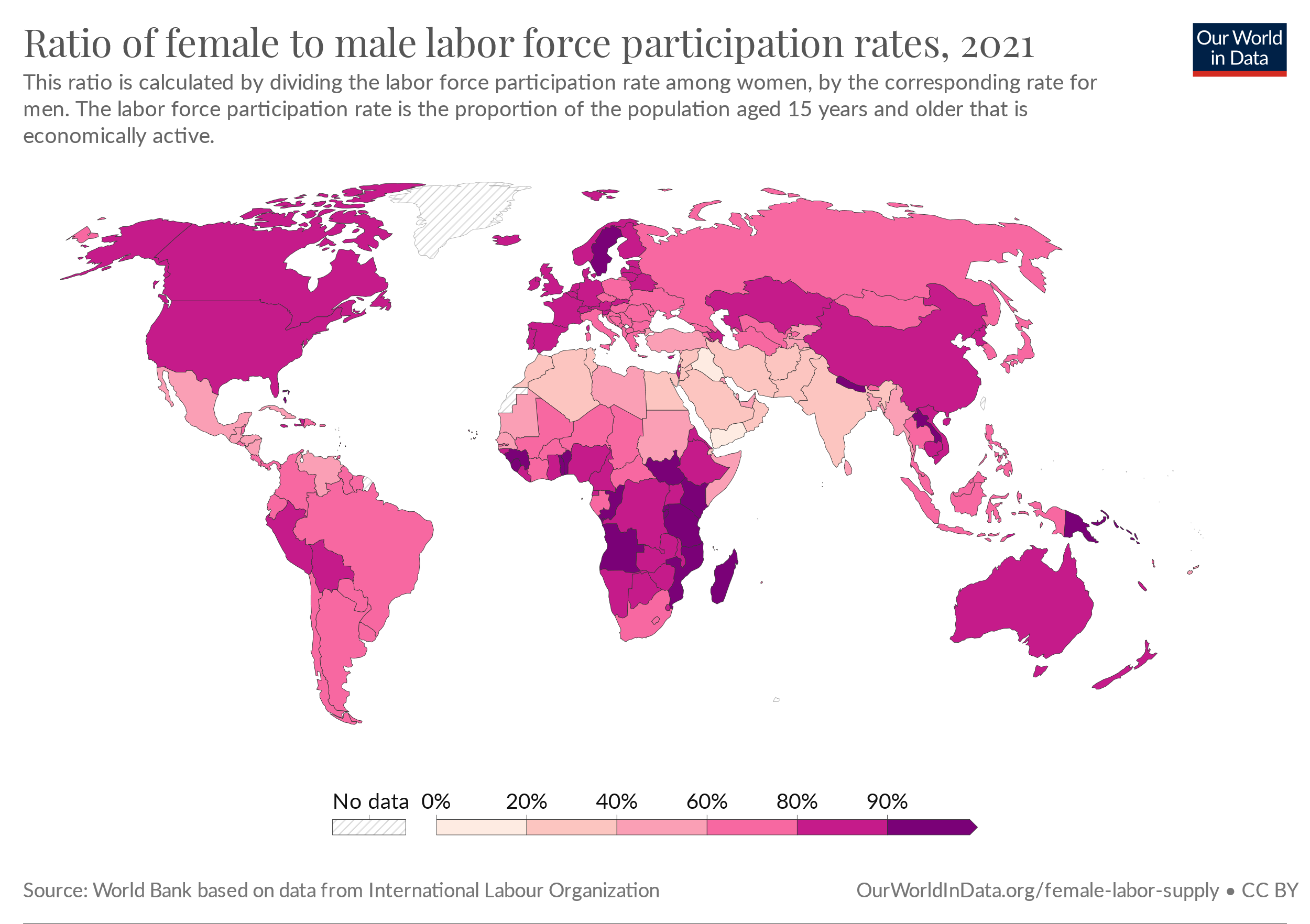

Figure 1: Female and male labour force participation as of 2021

Source: Our World in Data[39]

The G20 leaders, in the Bali Leaders’ Declaration, welcomed a new workplan—the Data Gaps Initiative (DGI). It should be noted that the International Monetary Fund (IMF) staff, in collaboration with the Financial Stability Board Secretariat and the Inter-Agency Group on Economic and Financial Statistics, have formulated a comprehensive workplan for the DGI aimed at generating data that is most urgently required for policy purposes. This workplan contains 14 recommendations that focus on addressing pressing policy requirements in key areas such as climate change, household income and wealth distribution, fintech and financial inclusion, and access to private sources of data and administrative data for improving the precision and immediacy of official statistics.[40] The policymakers of the G20 have acknowledged the necessity of acquiring superior data to tackle the increasingly intricate challenges they encounter and hence the DGI came to force.[41] Such advanced data acquisitions can be channelised to create an enabling policy environment specifically to tackle women’s entrepreneurship issues. For instance, data can be used to take empirical decisions about what enables women to start businesses efficiently, how they can embed climate resilient pathways in their projects, how governments can best track their progress, and how they can help women entrepreneurs collaborate with other entrepreneurs at national and international levels. Monitoring women’s entrepreneurship by collecting disaggregated data, will help understand the prevailing challenges women entrepreneurs face, build redressal schemes, and initiate efficient tracking of implementation of already existing laws and policies.

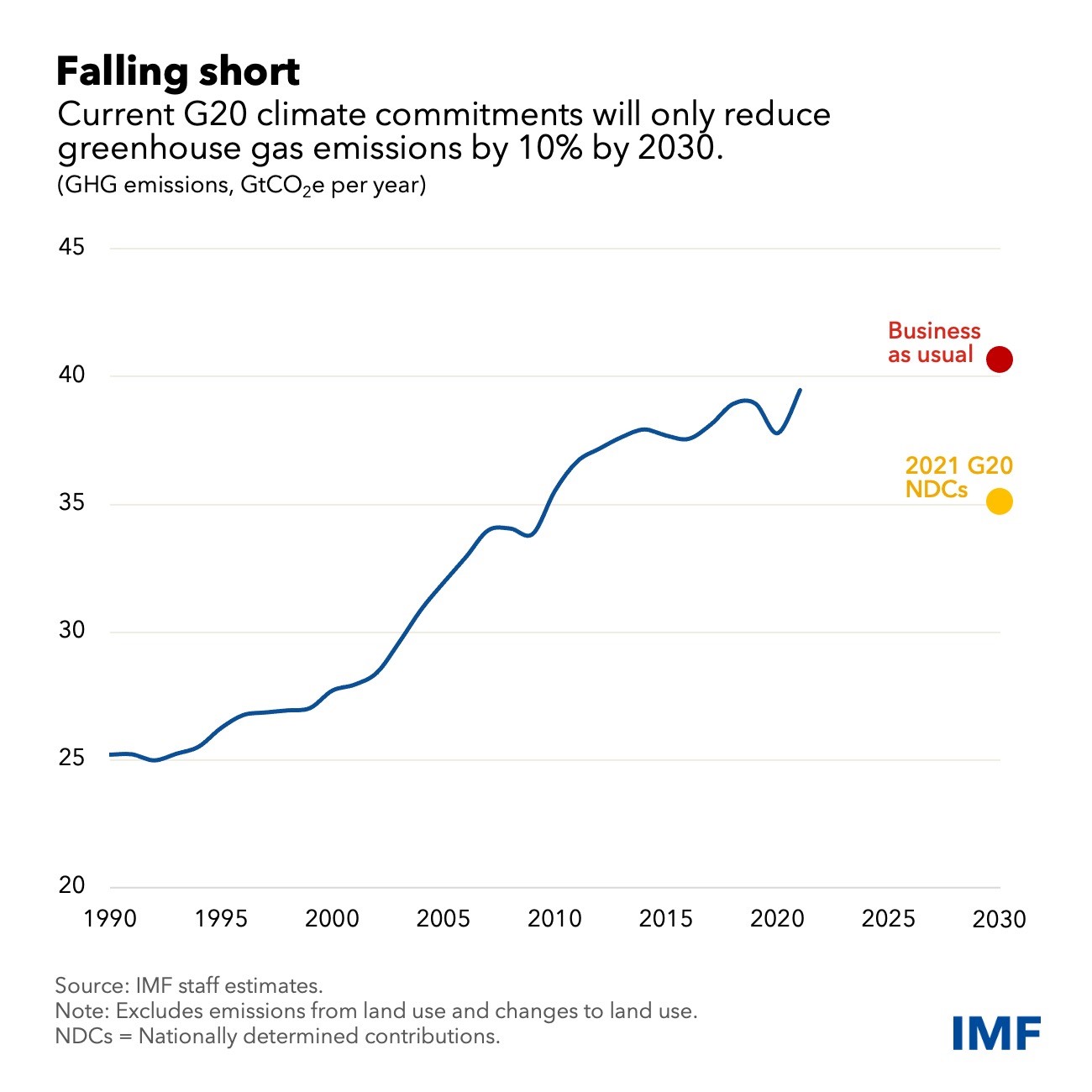

Further, the IMF has observed that bridging data gaps can help tackle the climate crisis. It has also noted that under the current G20 climate commitments, greenhouse gas emissions will only reduce by 10 percent by 2030[42] (Figure1) therefore, empowering women to embrace climate resilient business practices is crucial. Moreover, climate resilience monitoring can be done across specific sectors where women-led businesses are common, including their target markets—thereby evoking urban, rural, and coastline resilience pathways[43]—and aligning with the three pillars of the Race to Resilience campaign.[44]

Figure 2: How G20 Climate Commitments is Falling Short

Source: IMF[45]

- Government schemes to fund consultancies or private sector services that deliver free or subsidised climate risk assessment and adaptation planning to women-led businesses. Examples include the Small Business Innovation Research and Small Business Technology Transfer programs in the United States,[46] Women Entrepreneurship Strategy in Canada,[47] Acceleration Program in Tokyo for Women in Japan,[48] and the Stand-Up India Scheme.[49]

- Enabling easy access to technology for women entrepreneurs (especially from low- and middle-income countries, as well as rural and urban societies)[50]—thereby, bridging the digital-divide.

- Policy recommendations on assessing and enhancing the resilience of supply chains to climate-related risks including, diversifying suppliers, establishing alternative transportation routes, and implementing climate risk management strategies across supply chains.

- Social protection measures for women-led enterprises, prioritising social impact and financial sustainability.

3. Recommendations to the G20

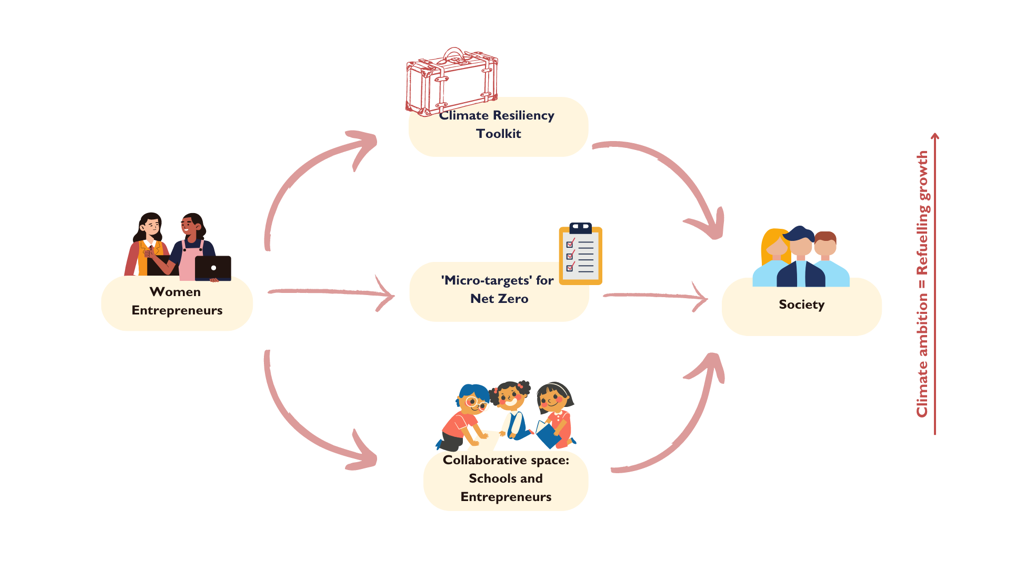

Figure 3: Women entrepreneurs and their impact to society

Source: Authors’ own

The G20 should endeavour to create a Climate Resiliency Toolkit for women entrepreneurs

The G20 leadership can create a Climate Resilience Toolkit (CRT) to help entrepreneurs (and specifically, women entrepreneurs) discover and utilise tools, information, and expertise regarding climate resilience pathways. Such a toolkit could benefit from monitoring and evaluation tools framed around gender-based disaggregated data, and a concrete vision to tether the private sector, through collective political will, to the cause of national and transnational women’s entrepreneurship. A CRT can also support enterprises by identifying collaborators, keeping track of carbon foot-prints, contributions to the circular economy, effective social protection measures available to endure shocks, legal assistance (even pro bono) that could be availed, and the government’s policy measures. This will particularly benefit women-led MSMEs, sustainable and green businesses focusing entirely on environmental objectives, and social enterprises that emphasise social impacts and pro-poor economic growth. Further, women entrepreneurs from rural and urban-rural backgrounds can benefit highly since the toolkit offers access to free and secure information, as well as opportunities to research and collaborate voluntarily. Further, the toolkit establishes authority for best practices in competitive market environments in the G20 countries. For instance, Climate Policy Radar, through the use of data science and Artificial Intelligence, offers tools that unlock global climate law and policy data.[51] Though it is based on law and policy alone, the not-for-profit start-up’s innovation and methodology offers best practices to use in developing a CRT and can be used to scale it up across the G20.

This can also lead to a G20-initiated app that enables cooperation from the private sector, to empower women entrepreneurs. This can create an enabling environment for peer-to-peer exchanges and advocacy initiatives to strengthen mutual commitments and be accountable to one another. Moreover, cooperation will lead to efficient cross-fertilisation of best practices related to climate resilient pathways for enterprises and effective advocacy of normative frames for socio-economic rights.

Setting net-zero micro-targets

The determination to achieve net-zero targets will have a significant impact on re-fuelling growth. Both, the post-pandemic recovery and climate ambition are important in this regard. The G20 can guide non-state actors (like, businesses and institutions) in setting short-term goals or ‘micro-targets’ to achieve net-zero emissions voluntarily. Such measures are necessary to avoid dangerous climate tipping points.

However, to ensure the effectiveness and credibility of these short-term goals, it is crucial to establish a science-based approach that filters out greenwashing practices. As such, it is important to define clear criteria and metrics for measuring progress. This could involve relying on reputable scientific research and consulting experts. The G20 can play a role in helping governments develop a transnational policy framework for reporting and monitoring these goals, which could provide transparency and comparability across businesses. Such a framework could enhance accountability and reduce the risk of misleading claims since reporting on progress is a voluntary decision of an enterprise.

Overall, a science-based approach to the reporting and monitoring framework, can enhance the credibility of climate related micro-targets that align with net-zero goals. In addition, such micro-targets can progressively compound to short, medium, and long-term targets, helping businesses take plausible steps towards the reduction of global emissions.[52]

Establishing a G20 initiated collaborative space for climate education for school children and women entrepreneurs

Article 6 of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change promotes collaborative and innovative approaches to climate change education and training, encouraging people to take initiative. Education is thus, key to building a sustainable future.[53] Nearly half (i.e., 47 percent) of the national curriculum frameworks of 100 countries is observed to have no reference to climate change.[54] The countries that do mention climate change in their documents, however, fail to explore it in depth.[55] The G20 leadership can play a huge role in creating a collaborative space that enables both climate-related education and women’s entrepreneurship. Further, developing best practices with respect to education, training, and sustainability can help Global North-South relations.

Attribution: Susan Ann Samuel, “Enhancing Women’s Entrepreneurship: Future-Proofing Law and Governance for Climate Resilience,” T20 Policy Brief, July 2023.

Endnotes

[1] “G20 Bali Leaders’ Declaration, 15-16 November 2022.” G20 Indonesia, https://www.g20.org/content/dam/gtwenty/gtwenty_new/about_g20/previous-summit-documents/2022-bali/G20%20Bali%20Leaders%27%20Declaration,%2015-16%20November%202022.pdf.

[2] United Nations Secretary-General, “Report of the open-ended intergovernmental expert working group on indicators and terminology relating to disaster risk reduction (A/71/644),” New York, United Nations, December 1, 2016, https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/852089?ln=en

[3] Richard Kinley, Michael Zammit Cutajar, Yvo de Boer, and Christiana Figueres, “Beyond Good Intentions, to Urgent Action: Former UNFCCC Leaders Take Stock of Thirty Years of International Climate Change Negotiations,” Climate Policy 21, no. 5 (May 28, 2021): 593–603, https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2020.1860567.

[4] United Nations, “Resolution Adopted by the General Assembly on 25 September 2015—Transforming Our World: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development”, New York, United Nations, October 2015, https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N15/291/89/PDF/N1529189.pdf?OpenElement

[5] United Nations, “Paris Agreement on Climate Change,” UN, 2015, https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/english_paris_agreement.pdf

[6] “The Evidence Is Clear: The Time for Action Is Now. We Can Halve Emissions by 2030,” IPCC, April 4, 2022, https://www.ipcc.ch/2022/04/04/ipcc-ar6-wgiii-pressrelease/

[7] Kinley, Cutajar, de Boer, and Figueres, “Beyond Good Intentions, to Urgent Action,” 593–603.

[8] “Secretary-General Calls on States to Tackle Climate Change ‘Time Bomb’ through New Solidarity Pact, Acceleration Agenda, at Launch of Intergovernmental Panel Report,” United Nations, March 20, 2023, https://press.un.org/en/2023/sgsm21730.doc.htm.

[9] Jessica Schnabel and Charlotte Keenan, “Initiatives Can Help Counter Coronavirus’ Impact on Women-Owned Businesses,” World Bank, November 23, 2020, https://blogs.worldbank.org/psd/initiatives-can-help-counter-coronavirus-impact-women-owned-businesses.

[10] Shalini Unnikrishnan and Cherie Blair, “Want to Boost the Global Economy by $5 Trillion? Support Women as Entrepreneurs,” BCG Global, January 8, 2021, https://www.bcg.com/publications/2019/boost-global-economy-5-trillion-dollar-support-women-entrepreneurs.

[11] Deepanshu Mohan et al., “What Are the Challenges Women Entrepreneurs Face in G20 Nations Despite Gender-Based Govt Reforms,” The Wire, May 3, 2023, https://thewire.in/women/what-are-the-challenges-women-entrepreneurs-face-in-g20-nations-despite-gender-based-govt-reforms.

[12] “India’s G20 Presidency Focuses on Women Empowerment,” The Print, February 14, 2023, https://theprint.in/world/indias-g20-presidency-focuses-on-women-empowerment/1371952/.

[13] Bain & Company and Google, Women Entrepreneurship in India: Powering the Economy With Her, Bain & Company and Google, 2019, https://www.bain.com/contentassets/dd3604b612d84aa48a0b120f0b589532/report_powering_the_economy_with_her_-_women_entrepreneurship_in-india.pdf

[14] Jonathan Woetzel et al., “The Power of Parity: Advancing Women’s Equality in Asia Pacific,” McKinsey & Company, April 23, 2018, https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/gender-equality/the-power-of-parity-advancing-womens-equality-in-asia-pacific.

[15] “Saudi Women Making Major Progress in Workplace,” Arabian Business, April 7, 2023, https://www.arabianbusiness.com/gcc/saudi-arabia/saudi-women-making-major-progress-in-workplace.

[16] “National Transformation Program,” Vision 2030, accessed June 8, 2023, https://www.vision2030.gov.sa/v2030/vrps/ntp/.

[17] Mohan et al., “What Are the Challenges Women Entrepreneurs Face in G20 Nations Despite Gender-Based Govt Reforms.”

[18] “Home,” Deutscher Startup Monitor, accessed June 7, 2023, https://deutscherstartupmonitor.de/.

[19] Emilia Cucagna, Leonardo Iacovone, and Eliana Rubiano-Matulevich, “Women Entrepreneurs in Mexico: Breaking Sectoral Segmentation and Increasing Profits” World Bank Policy Brief, October 2020, https://doi.org/10.1596/34697.

[20] Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, “Women at Work in G20 Countries: Progress and Policy Action,” OECD, 2019, https://www.oecd.org/g20/summits/osaka/G20-Women-at-Work.pdf.

[21] Mohan et al., “What Are the Challenges Women Entrepreneurs Face in G20 Nations Despite Gender-Based Govt Reforms.”

[22] “The Rose Review 2023 Outlines New Initiatives to Help More Women to Start and Build Thriving Businesses,” NatWest Bank, February 22, 2023, https://www.natwest.com/business/insights/business-management/leadership-and-development/rose-review-2023-new-initiatives-to-build-thriving-businesses.html.

[23] Global Entrepreneurship Monitor, Global Entrepreneurship Monitor 2022/2023 Global Report – Adapting to a ‘New Normal,’ London, GEM, 2023, https://gemconsortium.org/report/20222023-global-entrepreneurship-monitor-global-report-adapting-to-a-new-normal-2.

[24] OECD, “Women at Work in G20 Countries: Progress and Policy Action”

[25] OECD, “Women at Work in G20 Countries: Progress and Policy Action”

[26] European Commission and Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Policy Brief on Women’s Entrepreneurship, European Union and OECD, 2017, https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2767/50209.

[27] Mohammad Amin, “Do Banks Discriminate against Women Entrepreneurs?,” World Bank, April 30, 2009, https://blogs.worldbank.org/psd/do-banks-discriminate-against-women-entrepreneurs.

[28] Alison Wood Brooks, Laura Huang, Sarah Wood Kearney, and Fiona E. Murray, “Investors Prefer Entrepreneurial Ventures Pitched by Attractive Men,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 111, no. 12 (March 25, 2014): 4427–31, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1321202111.

[29] European Union and OECD, Policy Brief on Women’s Entrepreneurship.

[30] Cherie Blair Foundation for Women, “Resilience & Determination in the Face of Global Challenges: 2022 Audit of Women Entrepreneurs in Low and Middle Income Countries,” Cherie Blair Foundation for Women, 2022, https://cherieblairfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/Resilience-and-Determination-in-the-Face-of-Global-Challenges-2023-1.pdf.

[31] Jack Wrigley, “It’s Time for the Global North to Take Responsibly for Climate Change,” Global Social Challenges, July 16, 2022, https://sites.manchester.ac.uk/global-social-challenges/2022/07/16/its-time-for-the-global-north-to-take-responsibly-for-climate-change/.

[32] Valerie Hase, Daniela Mahl, Mike S. Schäfer, and Tobias R. Keller, “Climate Change in News Media across the Globe: An Automated Analysis of Issue Attention and Themes in Climate Change Coverage in 10 Countries (2006–2018),” Global Environmental Change 70 (September 1, 2021): 102353. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2021.102353.

[33] “Climate Change the Greatest Threat the World Has Ever Faced, UN Expert Warns,” United Nations, October 21, 2022, https://www.ohchr.org/en/press-releases/2022/10/climate-change-greatest-threat-world-has-ever-faced-un-expert-warns.

[34] “Universal Declaration of Human Rights 1948,” United Nations, accessed July 3, 2023, https://www.un.org/en/about-us/universal-declaration-of-human-rights.

[35] “International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights 1966,” United Nations, accessed July 3 2023, https://www.ohchr.org/en/professionalinterest/pages/cescr.aspx.

[36] Talal Rafi, “Why the World Needs to Invest in Female Climate Entrepreneurs,” Climate Champions, January 17, 2022, https://climatechampions.unfccc.int/why-the-world-needs-to-invest-in-female-climate-entrepreneurs/.

[37] United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, “Women in Business: Building purpose-driven enterprises amid crises,” New York, United Nations, November 2022, https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/diaeed2022d1_en.pdf

[38] Rafi, “Why the World Needs to Invest in Female Climate Entrepreneurs”

[39] Esteban Ortiz-Ospina and Sandra Tzvetkova, “Working women: Key facts and trends in female labor force participation,” Our World in Data, October 16, 2017, https://ourworldindata.org/female-labor-force-participation-key-facts.

[40] “G20 Leaders Welcome New Data Gaps Initiative to Address Climate Change, Inclusion and Financial Innovation,” IMF, November 28, 2022, https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2022/11/28/pr22410-g20-leaders-welcome-ndgi-to-address-climate-change-inclusion-financial-innovation.

[41] Bo Li and Bert Kroese, “Bridging Data Gaps Can Help Tackle the Climate Crisis,” IMF, November 28, 2022, https://www.imf.org/en/Blogs/Articles/2022/11/28/bridging-data-gaps-can-help-tackle-the-climate-crisis.

[42] Li and Kroese, “Bridging Data Gaps Can Help Tackle the Climate Crisis.”

[43] Global Climate Action UN Climate Change and Marrakech Partnership, “Climate Action Pathway-Climate Resilience: Vision and Summary,” Global Climate Action UN Climate Change and Marrakech Partnership, 2021, https://cdn.climatepolicyradar.org/navigator/XAA/1900/resilience-pathway-vision-and-summary_c06d91c81ec9e76cc71e2f423585f42e.pdf.

[44] “Race to Resilience,” Climate Champions, January 25, 2021, https://climatechampions.unfccc.int/race-to-resilience-launches/.

[45] Li and Kroese, “Bridging Data Gaps Can Help Tackle the Climate Crisis.”

[46] “About,” Small Business Innovation Research-United States, accessed June 10, 2023, https://www.sbir.gov/about.

[47] “Women Entrepreneurship Strategy,” Government of Canada, accessed May 3, 2023, https://ised-isde.canada.ca/site/women-entrepreneurship-strategy/en/women-entrepreneurship-strategy.

[48] “Home,” APT Women, accessed June 10, 2023, https://apt-women.tokyo/.

[49] “Standup India Scheme Features,” Standupmitra, accessed June 10, 2023, https://www.standupmitra.in/Home/SUISchemes.

[50] “Empowering Women Micro-Entrepreneurs through Mobile,” Mobile for Development, last modified February 21, 2023, https://www.gsma.com/mobilefordevelopment/resources/empowering-women-micro-entrepreneurs-through-mobile/.

[51] “Home,” Climate Policy Radar, accessed June 8, 2023. https://www.climatepolicyradar.org/.

[52] United Nations’ High-Level Expert Group on the Net Zero Emissions Commitments of Non-State Entities, “Integrity Matters: Net Zero Commitments by Businesses, Financial Institutions, Cities and Regions,” United Nations, 2023, https://www.un.org/sites/un2.un.org/files/high-level_expert_group_n7b.pdf.

[53] United Nations, “United Nations Framework Convention On Climate Change,” New York, United Nations, 2012, https://unfccc.int/resource/docs/convkp/conveng.pdf

[54] United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, “Getting Every School Climate-Ready: How Countries Are Integrating Climate Change Issues in Education,” Paris, UNESCO, 2021, https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000379591.

[55] UNESCO, “Getting Every School Climate-Ready”