Abstract

Despite strides in healthcare innovation, information technology, and delivery systems, global health systems continue to face complex challenges. Health Systems Strengthening (HSS) with Universal Health Coverage (UHC) is a priority for the G20 countries. Adopting the sustainability lens to analyse the current crisis, this Policy Brief argues that the existing UHC model requires a rethink. Advancing the Astana Declaration’s proposition that Primary Health Care (PHC) be brought together with UHC (UHC-with-PHC), this Brief suggests applying the tenets of the PHC approach to a continuum of healthcare (from home to tertiary care), i.e., PHC-with-UHC. Deepening and pluralising primary-level care and transforming the structure and functioning of secondary and tertiary services can make health systems sustainable and holistic. Additionally, PHC-with-UHC would include non-medical preventive action through whole-of-society and whole-of-government approaches. This Brief further offers alternate systems design principles to deliberate on how the G20 priority of HSS can become a reality.

- The Challenge

The world is facing a healthcare crisis, widely acknowledged even prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. While life expectancy has risen considerably over the 20th century, even in the low-and-middle-income countries (LMICs),[1] over 80 percent of this has been due to improved conditions of life, whereas 10–20 percent is attributable to health services specifically.[2] This rise in human longevity is now plateauing in high-income countries (HICs), even dipping in countries like the UK[3] and the USA.[4] Despite strides in healthcare and information technology, health systems are facing complex challenges globally with ballooning healthcare costs, growing health disparities, emerging illnesses and epidemics, and increasing fragility of ecosystems.[5] Be it socio-economic development or health services development, the world cannot continue with a ‘more of the same’ approach to find sustainable and holistic solutions to these challenges.

Considering the multi-dimensionality of the crisis, this Policy Brief examines the contemporary status of health services development (its cost and content) drawing from the three pillars of sustainability as outlined in the SDG discourse—economic viability, social justice, and environmental integrity.

Sustainability challenges of present health systems

Economic viability

Comparing available health expenditures (HE) data across selected countries (see Annexure 1), it is observed that:

- Of their total public expenditure, HICs are spending 13–24 percent on health services, while upper middle-income countries (UMIC) are spending between 9–18 percent, and lower middle- and low-income countries (LMIC, LIC) are spending between 3–9 percent of total public expenditure on health services.

- In per capita PPP dollar terms, the gaps increase manifold. Across the selected countries, on an average, public spending on health per capita (PPP dollars) by HICs is ten times more than that by UMICs and 66 and 202 times more than that spent by LMICs and LIC respectively.

- Taking public plus private in HE in PPP dollar terms, the selected HICs on an average had spent eight times more than UMICs, and 59-105 times more than LMICs and LIC. This means that the HE of countries such as Germany, the UK, Norway, and the USA in PPP dollar terms is more than or close to the national GDP per capita (in PPP dollars) of countries with low GDP such as India, Ghana, and Rwanda (e.g., US per capita HE is 1.6 times that of India’s GDP per capita, UK per capita HE is 9 times that of Rwanda’s GDP per capita).

HICs with older populations have higher care needs, albeit with marginal impact on overall cost.[6] Yet, the gaping differences and the projected continuing escalation of HICs HE[7] beg the question of whether it is possible for the whole world to spend the equivalent of HICs on healthcare in the visible future.

Even health outcomes in terms of life expectancy (LE) graded from 84 years in HICs to 66 years in LICs are not commensurate with financial inputs. Thailand, for instance, has only a two-year difference in LE with the UK, even as HE per capita differential is seven times and has the same LE as the USA despite fifteen times lower HE, raising serious questions about the health systems design of HICs.

Evidently, the high expenditure with debatable cost-effectiveness renders the universalisation of the healthcare systems of HICs questionable. It indicates that healthcare systems must be redesigned to remain fiscally sustainable while responding holistically to people’s healthcare needs for all countries, including HICs.

Countries with low public spending on health must increase their allocations for a viable universal healthcare system, but they will likely get better outcomes if they adopt more cost-effective designs.

Value, effectiveness, and safety of healthcare

Given the centrality of health for human wellbeing, high expenditures on health services may be justified and desirable if they create welfare benefits for health, economic, and social development goals.

The normative structure of the HIC design of health services is predominantly institutional care focused, with biomedical pharmaceuticalisation, medical procedures, and lifestyle change for impact on biomedical parameters.[8] Diagnostic technologies, pharmaceutical products, medical procedures, and hospital-based services have become increasingly costlier. Insurance and third-party arrangements add to these expenses.[9] Commercialisation of healthcare[10] by the medical-industrial complex, privatisation, and the weakening of publicly provisioned systems have created over-medicalisation, with unnecessary interventions on a large scale[11] making healthcare inaccessible to most.[a]

Besides adding to the direct financial costs of healthcare, over-medicalisation leads to an increase in iatrogenesis, i.e., medical intervention-generated ill health.[12] This creates ill health and unaffordability for patients as well as causing suffering among medical providers who are pressurised to go against their clinical judgement and over-prescribe or cut corners. This has resulted in many physicians leaving clinical practice due to ‘moral burnout’.[13]

Additionally, LMICs suffer from lower public expenditure on healthcare which, in imitating HICs, gets disproportionately channelled to secondary and tertiary care rather than to the more cost-effective primary-level care.[14] Inadequate public services and limited access lead to malpractice nexuses that increasingly promote corruption.[15]

Social justice

The unaffordable design of health services leads to widening inequalities in access. Unjust distribution of material resources and services (e.g., livelihoods, food, housing, safe water and air, education) and cultural capital results in inequalities of health status, creating greater healthcare needs among the most disadvantaged. Social hierarchies based on gender, race, caste, etc., as well as social ‘othering’ leads to discriminatory policies, institutional systems, and behaviours of healthcare providers. This prevents access to services by socially marginalised groups.[16]

Delegitimisation of more ecological and holistic health knowledge is another dimension of social and cultural injustice that has further limited the ability to address these challenges effectively. On the other hand, information asymmetry and mutual distrust between patients and providers results in poor behaviour towards patients and communities as well as violence against doctors.[17]

International injustice is equally important when health resources such as vaccines are in short supply, and HICs are able to hoard them while LMICs suffer.

Environmental integrity

The pharmaceutical industry, on which the modern practice of medicine is completely dependent, is one of the biggest polluters of water, soil, and air.[18] Without adequate regulations and guidelines, modern production methods of herbal medicines fail to include the ethics of conserving/restoring raw materials, begetting the extinction of several medicinal plants.

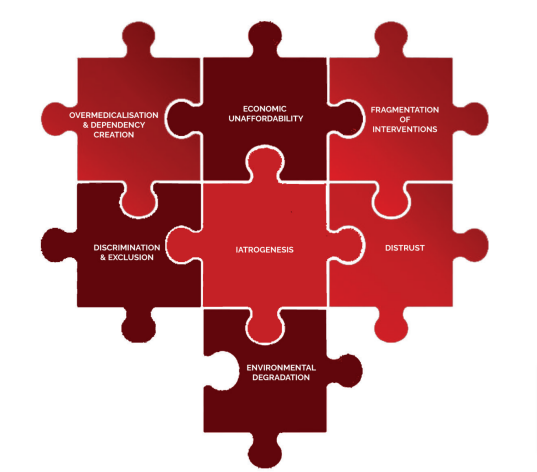

Thus, present health systems design is counter to the requirements of sustainable healthcare, violating all its three pillars (Figure 1). What makes medical services—an essential human need and right of each individual—unaffordable and inaccessible is the systems design, its infrastructural models, and its mechanism for production, distribution, and choice of technologies.

Figure 1: Components of the Healthcare Crisis

Source: Authors’ own

- The G20’s Role

SDG-3, “healthy lives for all at all ages”, explicitly focuses on health services and proposes the UHC as the strategy for meeting the goal. UHC involves continuing and spreading doctor-hospital-centred healthcare throughout the world, with a proposed decrease in catastrophic health expenditures through insurance systems, public or private. However, as discussed earlier, if the doctor-hospital model of healthcare is to be universalised with the standards set by HICs, it may prove to be a mirage for most LMICs. This is neither a desirable nor a cost-effective model for HICs themselves. The pandemic demonstrated that primary-level services are critical for effective healthcare[19] and diagnosis, highlighting the need for a more nuanced approach to the universalisation of healthcare.

Global vision documents that underscore the need for strengthening primary-level care for UHC[20] fail to address the design issues underlying the dominant hospital-based healthcare model, which is becoming increasingly unviable, unsustainable, unfair, and even unhealthy. Primary-level services developed in several countries as PHC remain subservient to the secondary and tertiary services (See Annexure 1.2). The linking of the primary with the secondary and tertiary in the UHC-with-PHC formulation of the Astana declaration (2018),[21] without the explicit adoption of PHC principles, will only bring the over-medicalised approach into primary-level services with all its unaffordability, iatrogenesis, and dependency-creating features.

However, if the positive intent of UHC in universalising access to hospital services is viewed as a measure to extend the Health for All agenda of the Alma Ata declaration[22] (see Appendices), a PHC-with-UHC approach would mean strengthening primary-level care linked to non-medical preventive action (food security and safety, safe water and air, healthy workspaces, etc.) through whole-of-society and whole-of-government approaches and extending the PHC principles to secondary and tertiary care services. Extending PHC principles to overall healthcare would entail a rethink of the organisational structure, financing, and clinical content of secondary and tertiary services. Thus, for sustainable and holistic healthcare, a PHC-with-UHC approach needs to be adopted with the following features:

Integration across levels of care, between institutions, sectors, and sub-populations/communities

- Create structures and practices that make health central to development in all sectors through an optimum whole-of-government approach for Health in All Policies (HiAP);

- Maximise synergies between different sectors dealing with human, animal, and ecological health;

- Centre the perspective of the marginalised and address social determinants of health (which is not only fair but also cost-effective)[23] by preventing health inequities, associated complications, and subsequent requirements of expensive care; adopt a whole-of-society approach with attention to the hierarchy of power and access to resources within ‘the community’; address differential healthcare needs such as those of gendered healthcare, indigenous peoples, occupational health, mental health and wellbeing, and healthy ageing;

- Equip and facilitate people for better self-care; capacitate professionals and communities for implementing the principles of preventive and clinical care, including how to draw the line between the need for medical intervention and when it is not required or when it should be stopped.

Extension of PHC principles to all levels of care

The principles of PHC enshrined in the landmark Alma Ata declaration to be applied to the secondary and tertiary levels include the following:

- People-centredness

- Proximity to home

- Available, affordable, and accessible

- Fulfilling epidemiologically assessed ‘need’ for healthcare, especially of the most vulnerable sections

- Respecting traditional healers for their relationship of trust with communities

- Community participation and self-reliance

- Prioritising the use of appropriate technology that is cost-effective, affordable, easily deliverable, and promotes self-reliance

Adoption of appropriate technology, including plural epistemologies

- Adopt appropriate technologies as a norm by strengthening health technology assessments based on the ethics of healthcare, equitable access to pharmaceutical products and vaccines, integrative health systems using plural knowledge systems rationally, and determining the appropriate level (from community-based to primary/secondary/tertiary institutions) for locating the use of optional technologies based on cost-effectiveness and expertise.

- Acknowledge and enable epistemological diversity[b] across various health knowledge systems and their legitimacy and relevance as knowledge and as practices, and build evidence for integrative practice using multiple methodological approaches, including systems biology, bio-psycho-social, and practice-based evidence.

- Decolonise and democratise health knowledge with contextualised prevention and patient-centred healthcare in opposition to the dominant one-size-fits-all uniform techno-centric hospital-based care.

A discursive shift towards holistic health systems thinking

Such a shift aims to reverse the fragmentation between the following:

- Conventional biomedical interventions and upstream public health

- Intended outcomes of health and other sectors

- Secondary and tertiary level, separated from primary level structurally in their values and functional principles

- Conventional biomedical and other health knowledge systems, as well as the biomedical and social sciences

- Clinical care and social support services

As the example of Thailand[24] shows, best practices[25], [26] from across the world may be analysed and appropriate lessons incorporated towards developing context-appropriate PHC-with-UHC designs.

Against this backdrop, the G20 theme of Health System Strengthening (HSS) with UHC requires deliberation on the various approaches offered as solutions to the healthcare crisis. As this Brief suggests, the world needs to take a further leap towards a shift in paradigm from the present articulation of the UHC-with-PHC approach to the PHC-with-UHC approach, which provides multiple pathways to the multi-dimensional crisis (Figure 2 for operational implications).

Figure 2: Comparison of UHC-with-PHC and PHC-with-UHC Systems Design with Respect to Solutions for Addressing the Healthcare Crisis

Source: Authors’ own, adapted from previous research[27],[28],[29]

- Recommendations to the G20

The G20 is well placed to facilitate a global dialogue towards:

- Creating a public policy discourse for sustainable and people-empowering healthcare systems;

- Making the health of humans, animals, and plants in their ecosystems (the One Health conceptualisation) the centre of all socio-economic development; adopting HiAP as the conceptualisation of governance structures and processes to identify negative consequences of public policy (e.g., industrial pollution), and driving positive contributions for health (e.g., agriculture to prioritise food security and safety);

- Working towards a global declaration on the principles for PHC-with-UHC at a global conference by initiating wide consultative national and regional processes involving public institutions, civil society, and social movements and drawing from global best practices;

- Supporting health systems research and policy studies through priority funding and institutional strengthening to generate PHC-with-UHC systems designs for diverse contexts.

Reiterating the principles of PHC and generating context-appropriate PHC-with-UHC systems designs is essential. The rationalisation of institutional design at all levels based on the principles of PHC will allow for a more sustainable operational reconceptualisation[30] of the WHO’s six building blocks. With this conceptual shift, the utilisation of digital health for PHC-with-UHC, robust pandemic preparedness, rational R&D in health technology sectors, and equitable distribution of products would be more suited to meet people’s needs and ensure effectiveness. It could be the win-win approach for everyone in the healthcare system, including users, care providers, administrators, and policymakers.

Appendices

Alma Ata Report: https://www.unicef.org/media/85611/file/Alma-Ata-conference-1978-report.pdf

Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/ottawa-charter-for-health-promotion

Astana Declaration: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/primary-health/declaration/gcphc-declaration.pdf

WHO-UNICEF Vision for Primary Health Care in the 21st Century: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/328065/WHO-HIS-SDS-2018.15-eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

Walking the Talk: Reimagining Primary Health Care after COVID-19: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/36005695-0123-5ecf-88c9-043559c21479/content

The Convention on Biological Diversity: https://www.cbd.int/convention/

Sustainable Development Goals: https://sdgs.un.org/goals

The WIPO Intergovernmental Committee on Intellectual Property and Genetic Resources, Traditional Knowledge and Folklore (IGC): https://www.wipo.int/tk/en/igc/

Annexures

Annexure 1

Table 1presents an assessment of country-level health expenditures, UHC service coverage index, and life expectancies at birth (figures rounded to the nearest whole number). All G20 countries (except in the EU) and selected others that have made strides towards UHC have been included.[31] These countries are listed in descending order of their GDP per capita in Purchasing Power Parity (PPP) terms.

Table 1 : Levels of Health Expenditures, UHC Service Coverage Index, and Total Life Expectancy of G20 and Other Countries That Have Made Strides Towards UHC

| Country

(1) |

GDP Per Capita PPP for 2019 (Constant 2017 International $)

(2) |

Domestic General Government Health Expenditure

|

Current Health Expenditure (Public + Private) per capita in US $ for 2019 (Constant 2020, PPP $)

(6) |

UHC Service Coverage Index for 2019 (Scale: 0-100)

(7) |

Total Life expectancy at Birth in 2019

(Years)

(8) |

||

| as % of GDP for 2019

(3) |

as % of General Government Expenditure for 2019

(4) |

per capita for 2019 (Constant 2020, PPP $)

(5) |

|||||

| High Income Countries* | |||||||

| Norway | 64983 | 9 | 18 | 6864 | 8007 | 86 | 83 |

| USA | 62471 | 9 | 22 | 5495 | 10661 | 85 | 79 |

| Denmark | 56814 | 8 | 17 | 5072 | 6059 | 82 | 81 |

| Iceland | 56584 | 7 | 16 | 4856 | 5865 | 89 | 83 |

| Germany | 53874 | 9 | 20 | 4227 | 5478 | 88 | 81 |

| Sweden | 52851 | 9 | 19 | 4812 | 5653 | 85 | 83 |

| Australia | 49379 | 8 | 17 | 4100 | 5555 | 87 | 83 |

| Canada | 49176 | 8 | 19 | 3547 | 5084 | 91 | 82 |

| Finland | 48583 | 7 | 14 | 3577 | 4460 | 85 | 82 |

| UK | 47088 | 8 | 20 | 3422 | 4265 | 87 | 81 |

| Saudi Arabia | 47025 | *** | *** | *** | *** | 72 | 77 |

| France | 45923 | 8 | 15 | 3389 | 4508 | 84 | 83 |

| Republic of Korea | 42759 | 5 | 14 | 1545 | 2595 | 89 | 83 |

| Italy | 42739 | 6 | 13 | 2146 | 2911 | 85 | 83 |

| Japan | 41654 | 9 | 24 | 3682 | 4379 | 83 | 84 |

| Upper Middle-Income Countries | |||||||

| Turkiye | 28150 | 3 | 9 | 309 | 397 | 77 | 78 |

| Russian Federation | 27255 | 3 | 10 | 400 | 654 | 79 | 73 |

| Argentina | 22072 | 6 | 16 | 613 | 959 | 78 | 77 |

| Mexico | 20065 | 3 | 10 | 272 | 553 | 74 | 74 |

| Thailand | 17997 | 3 | 14 | 213 | 294 | 82 | 79 |

| China | 15978 | 3 | 9 | 302 | 540 | 81 | 78 |

| Brazil | 14685 | 4 | 10 | 346 | 850 | 75 | 75 |

| Colombia | 14616 | 6 | 18 | 372 | 523 | 80 | 77 |

| South Africa | 13852 | 5 | 15 | 322 | 550 | 71 | 66 |

| Cuba | 8042.9** | 10 | 16 | 902 | 1013 | 83 | 78 |

| Lower Middle-Income Countries | |||||||

| Sri Lanka | 13639 | 1 | 7 | 58 | 142 | 66 | 76 |

| Indonesia | 11858 | 1 | 9 | 59 | 121 | 56 | 71 |

| Philippines | 8732 | 2 | 8 | 142 | 58 | 60 | 72 |

| India | 6617 | 1 | 3 | 20 | 61 | 64 | 71 |

| Ghana | 5346 | 1 | 7 | 30 | 74 | 46 | 65 |

| Low Income Country | |||||||

| Rwanda | 2191 | 3 | 9 | 20 | 51 | 47 | 66 |

* Countries are classified based on the World Bank’s latest income classification [https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519]

** In GDP per capita (constant 2015 US$) terms, as later data is not available.

*** Data unavailable

Note: Table 1 is developed by the authors from existing databases.

Sources: Columns 2, 7, and 8 from World Bank, https://data.worldbank.org/; Columns 3-6 from WHO Global Health Expenditure Database, https://apps.who.int/nha/database/Select/Indicators/en

Annexure 2

Diverse interpretations of UHC and PHC

Universal Health Coverage has been defined as “the desired outcome of health system performance whereby all people who need health services (promotion, prevention, treatment, rehabilitation, and palliation) receive them, without undue financial hardship”.[32] It was to be implemented as a Health Systems Strengthening design that would protect people from ‘catastrophic expenditures’ on medical care through incremental increase in: (i) the population covered with medical insurance so as to get free healthcare at the point of service, (ii) the health problems and medical interventions included in the cover, starting with a minimal essential package of services, and (iii) the proportion of total healthcare expenditures covered.

The initial UHC design creates affordability by ‘risk pooling’ to “prevent catastrophic medical expenditures”,[33] thereby universalising more of the same biomedicine-based hospital systems through insurance-based financing. Its model of making healthcare affordable is by either getting people to buy private insurance to pay for private-sector provisioning of services in response to their anxiety about unaffordable medical care or using public tax or cess funds for social insurance.

However, the design adopted for UHC in various countries differs from the definition. In Thailand, India, and Cuba, hospital and primary-level services are provided free through state provisioning, which has led to the strengthening of primary-level services in the public system and social insurance cover for secondary and tertiary care. However, implementation has been much more effective in Thailand and Cuba (where public systems have been substantially strengthened at all levels) than in Brazil and India (which have more fragmented systems between public and private sectors and the various levels). In Brazil’s Universal Health System, there is no essential package of services, but all services are to be provided as per need. In India, there is some strengthening of the public services package at the primary level under the UHC rubric and social insurance for the poorest 40 percent for hospital services through the public or private sector, with some states providing social insurance cover to all citizens.

These countries also reflect the diverse interpretations of PHC. “There are three versions of PHC itself: (i) Primary level care with a feasible, affordable, ‘essential healthcare’ package that has become known as Selective Primary Health Care, based on primary level care and ‘community mobilisation’ through the campaign mode, as adopted for the RCH and Polio Eradication programmes. (ii) Comprehensive Primary Health Care (CPHC) with primary level care as central to HSD (health systems development) and appropriate secondary and tertiary care to support it, including medical and non-medical interventions that are preventive, promotive, curative and rehabilitative. (iii) CPHC that includes the local folk knowledge-based home and community care at primary level, backed up by the institutional primary, secondary and tertiary levels.”[34] The designs for the third version have been articulated in various ways, such as by adding a ‘fourth tier’ to the three tiers of the Alma Ata pyramidal design[35] or a five-layer design visualised as concentric circles with the individual, family, and community at the centre.[36]

Attribution: Ritu Priya et al., “Universalising Health Coverage or Crisis? Contours of the Challenges and Solutions,” T20 Policy Brief, July 2023.

Endnotes

[a] The USA experience with private insurance demonstrates its inadequacy in preventing catastrophic expenditures and ensuring access while also adding to the costs of the system. Relative to other HICs, the USA spends almost double per capita PPP dollars on health but has attained the least coverage and life expectancy among them. 41 percent of US adults carry medical debts, with one in every eight individuals owing more than US$10,000 (Donald M. Berwick, “Salve Lucrum: The Existential Threat of Greed in US healthcare”, JAMA Network 329, no.8 (January 2023): 629-30, doi:10.1001/jama.2023.0846).

[b] Diverse health knowledge systems have addressed the healthcare needs of populations through cost-effective and value-based, contextualised approaches for generations. Due to their inherent design, they balanced positive health (through preventive and promotive approaches) at the individual level through ideas such as svasthya (a Sanskrit term denoting optimal health, literally meaning “to be established in one’s self or own natural state”) with the community, nature, and ecosystems. Significantly, such practices, despite their long existence in LMICs (through either codified system such as ayurveda, unani, and traditional Chinese medicine or diverse local health traditions) have been marginalised through the techno-centric, biomedicalised, and institution-centred care by a dominant reductionist approach. Instead, creating empowered self-reliant communities in primary healthcare; emphasising localisation; preserving natural resources; and protecting the interrelation between human, animal, and local ecosystems by integrating holistic approaches such as One Health and Planetary Health, not with a risk perception and surveillance approach, but with a positive health view, should be the way forward.

1 Josephine Moulds, “Chart of the Day: How Life Expectancy has Changed Over 200 Years,” World Economic Forum, November 30, 2017, https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2017/11/chart-of-day-life-expectancy-200-years.

[2] Truman Du, “Charted: Healthcare Spending and Life Expectancy, by Country,” Visual Capitalist, accessed April 05, 2023, https://www.visualcapitalist.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/Top-30-countries-by-life-expectancy-increase-since-1960-Full.html.

[3] Louise Marshall et al., “Mortality and Life Expectancy Trends in the UK,” Health Foundation, November 2019, https://www.health.org.uk/publications/reports/mortality-and-life-expectancy-trends-in-the-uk.

[4] “CDC Director’s Media Statement on U.S. Life Expectancy,” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, last reviewed November 29, 2018, https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2018/s1129-US-life-expectancy.html.

[5] “Urgent Health Challenges for the Next Decade,” World Health Organization, January 13, 2020, https://www.who.int/news-room/photo-story/photo-story-detail/urgent-health-challenges-for-the-next-decade.

[6] “The Long-Term Outlook for Health Care Spending,” Congressional Budget Office, December 13, 2007, https://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/cbofiles/ftpdocs/87xx/doc8758/maintext.3.1.shtml.

[7] Luca Lorenzoni et al., “Health Spending Projections to 2030: New Results Based on a Revised OECD Methodology,” OECD Health Working Paper 110 (May 23, 2019), https://one.oecd.org/document/DELSA/HEA/WD/HWP(2019)3/En/pdf.

[8] Robert Kuttner, “Market-Based Failure — A Second Opinion on U.S. Health Care Costs,” The New England Journal of Medicine 358, no.6 (February 2008): 549, https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/nejmp0800265.

[9] Kuttner, “Market-Based Failure”

[10] David McCoy, “Commercialisation is Bad for Public Health,” British Medical Journal 344 (January 2012), https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.e149.

[11] “Understanding the Opiod Overdose Epidemic,” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, last reviewed June 1, 2022, https://www.cdc.gov/opioids/basics/epidemic.html.

[12] Martin A. Makary and Michael Daniel, “Medical Error—The Third Leading Cause of Death in the US,” British Medical Journal 353, i2139 (2016), https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i2139.

[13] Eric Reinhart, “Doctors aren’t Burned Out from Overwork. We’re Demoralized by Our Health System,” The New York Times, February 5, 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/02/05/opinion/doctors-universal-health-care.html.

[14] Kara Hanson et al., “The Lancet Global Health Commission on Financing Primary Health Care: Putting People at the Centre,” The Lancet 10, no. 5 (May 2022): e717, https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(22)00005-5.

[15] Emily H. Glynn. “Corruption in the Health Sector: A Problem in Need of a Systems-Thinking Approach,” Frontiers in Public Health 10, no. 910073 (August 2022): 7, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.910073.

[16] Rama Baru et al., “Inequities in Access to Health Services in India: Caste, Class and Region,” Economic and Political Weekly 45, no. 3 (September 2010): 49, http://www.jstor.org/stable/25742094.

[17] Dinesh C. Sharma, “Rising Violence Against Health Workers in India,” Lancet 389, no. 10080 (2017): 1685, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31142-X.

[18] “Drugged Waters – How Modern Medicine is Turning into an Environmental Curse,” UN Environment Programme, August 06, 2018, https://www.unep.org/news-and-stories/story/drugged-waters-how-modern-medicine-turning-environmental-curse.

[19] Katherine E. Bliss, “Promoting Primary Health Care during a Health Security Crisis,” Centre for Strategic & International Studies, April 29, 2022, https://www.csis.org/analysis/promoting-primary-health-care-during-health-security-crisis.

[20] World Health Organization, “Declaration of Astana,” 2018, https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-HIS-SDS-2018.61.

[21] World Health Organization, “Declaration of Astana”

[22] World Health Organization, “Declaration of Alma-Ata,” 1978, https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-EURO-1978-3938-43697-61471.

[23] Melanie Bush, “Addressing the Root Cause: Rising Healthcare Costs and Social Determinants of Health,” North Carolina Medical Journal 79, no. 1 (2018): 28, https://doi.org/10.18043/ncm.79.1.26.

[24] Suriwan Thaiprayoon and Suwit Wibulpolprasert, “Political and Policy Lessons from Thailand’s UHC Experience,” Issue Brief No. 174, Observer Research Foundation, 2017, https://www.orfonline.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/ORF_IssueBrief_174_ThailandUHC.pdf.

[25] Tony Delamothe, “Founding Principles,” British Medical Journal 336, no.7655 (May 2008):1216-18, https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.39582.501192.94.

[26] Ashoka J. Prasad, “Primacy of Primary Healthcare: Cuban Experience and Lessons for India,” The Indian Practitioner 73, no.9 (September 2020): 9-10, https://articles.theindianpractitioner.com/index.php/tip/article/view/1049.

[27] Mahesh Madhav Mathpati et al., “Population Self-Reliance in Health’ and COVID-19: The Need for a 4th Tier in the Health System,” Journal of Ayurveda and Integrative Medicine 13, no.1, (January-March 2022): 3-6, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaim.2020.09.003.

[28] Prachinkumar Ghodajkar et al., “Towards Re-Framing Operation Design for HFA 2.0: Factoring in Politics of Knowledge in Health Systems,” Medico Friend Circle Bulletin 380 (February 2019): 23-24, http://www.mfcindia.org/mfcpdfs/MFC380.pdf.

[29] Ritu Priya et al., “Questioning Global Health in the Times of COVID-19: Re-imagining Primary Health Care Through the Lens of Politics of Knowledge,” Humanities and Social Sciences Communication 10 (May 2023): 3-8, https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01741-8.

[30] Priya et.al., “Questioning Global Health in the Times of COVID-19”

[31] “Chapter 4 Health Finance Indicators,” in National Health Profile – 2017 (New Delhi: Central Bureau of Health Intelligence, 2017), 206, https://www.cbhidghs.nic.in/WriteReadData/l892s/Chapter%204%20Health%20Finance%20Indicators.pdf.

[32] World Health Organization, “Tracking Universal Health Coverage: First Global Monitoring Report,” 2015, https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241564977

[33] World Health Organization, “The World Health Report: Health Systems Financing: The Path to Universal Coverage,” 2010, https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/44371.

[34] Ritu Priya, “State, Community, and Primary Health Care: Empowering or Disempowering Discourses,” in Equity and Access: Health Care Studies in India, ed. Purendra Prasad and Amar Jesani (New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2018), https://www.researchgate.net/publication/334512643_State_Community_and_Primary_Health_Care_Empowering_or_Disempowering_DiscoursesEmpowering_or_Disempowering_Discourses.

[35] Mathpati et al., “Population Self-Reliance in Health”

[36] Ghodajkar et al. “Towards Re-Framing Operation Design for HFA 2.0”