Task Force 7: Towards Reformed Multilateralism: Transforming Global Institutions and Frameworks

Abstract

This policy brief examines the growing coordination between China and Russia within the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) and its implications for the rules-based international order. Driven by a desire to counterbalance the US, the ‘Dragonbear’ alliance poses significant challenges to the effectiveness of the UNSC and other multilateral institutions, including the G20. The primary recommendations for the G20 are to reassess the China-Russia relationship, fortify the rules-based international order, encourage dialogue and cooperation, advocate for UNSC reform, and reinforce alliances and coalitions with likeminded partners. India’s unique position in various multilateral structures and its leadership role in the G20 this year make it a key player in balancing diverging interests and fostering collaborative efforts to address the challenges posed by the rise of the Dragonbear.

1. The Challenge

The United Nations (UN) was established 75 years ago to maintain international peace and security and encourage multilateral diplomacy. However, global power competition between the US and China, along with Russia’s growing assertiveness, has diminished the effectiveness of the UN Security Council (UNSC). The rise of the ‘Dragonbear’[a] and the bifurcation[b] of the global system pose significant geopolitical challenges to the rules-based international order.

Currently, global diplomacy is undergoing a considerable shift. The UNSC, tasked with upholding international peace and security, has been deeply affected by the power shift from the Atlantic to the Pacific, and the emerging systemic conflict between the US and China. The COVID-19 pandemic has further accelerated these changes, with regional actors forming ad hoc alliances based on their geopolitical and geoeconomic interests in a world marked by a growing bifurcation of the global system and disintegrating multilateral structures.[1]

This evolving landscape has led to the ‘bilateralisation’ of international relations, generating a monumental shift that places tremendous pressure on international organisations and institutions.[2] The systemic rivalry between the US and China, spanning various spheres of competition—from trade and economics to technology, diplomacy, and international organisations—has significantly increased uncertainty within the UNSC, as Russia’s war against Ukraine has revealed most recently.[3] Consequently, the international body now confronts escalating pressure from both Beijing and Moscow, signalling the necessity for policymakers to adapt to this changing global context.

In recent years, the context of global power competition has undergone a profound shift, as the UNSC grapples with challenges stemming from China’s rise and Russia’s resurgence. The growing competition between democratic and authoritarian models of governance has disrupted the international rules-based order.[4] Moreover, the US’ retreat from its international commitments under Trump’s administration has led to increasing disunity within the transatlantic community. This has paved the way for the Dragonbear to increase the pressure on the US-led global order as well as promote alternative forms and narratives of multilateralism.[5]

The weakening of the UNSC is linked to the decline of Washington’s international role, especially during Trump’s tenure, and the rising assertiveness of China and Russia as diplomatic powers. The latter has created a two-fronts scenario for the West centred around Ukraine and Taiwan.[6] As Western democracies re-evaluate their foreign and security policy stances on China and Russia following Moscow’s invasion of Ukraine and Beijing’s subsequent diplomatic support, it is crucial to understand this changing global landscape and explore ways to strengthen the rules-based international order while addressing the challenges posed by the Dragonbear.

Dragonbear’s veto behaviour as a balancing act against the West

The Sino-Russian relationship has become increasingly multifaceted and complex over the past fifteen years, with both nations seeking to disrupt the US-led global order on many occasions. They have found common ground in their shared understanding of a transforming global landscape and its potentially dangerous consequences. Increasingly, coordinating their diplomatic, military, and strategic efforts to counterbalance American influence in global affairs, the Dragonbear has adopted the principle of “not always with each other, but never against each other.” [7] This approach has achieved complementarity at the highest political levels, leading to a comprehensive strategic partnership centred on international law and organisations.

The Dragonbear’s strengthened role within the institutional framework enables Russia and China to exert greater influence in their relations with third countries and impose their solutions to conflicts based on a shared understanding and common interest. Their increased prestige, authority, and leadership, along with the powerful tool of their veto in the UNSC, allow them to navigate intricate geopolitical situations and secure long-term benefits. As the US’ interest in various international organisations, such as the World Health Organization, the UN Human Rights Council, and the Paris Accords has been fading away, Russia and China have been capitalising on the opportunity to advance their vision of multilateralism and further solidify their position on a broad range of international topics within organisations of their choosing.[8]

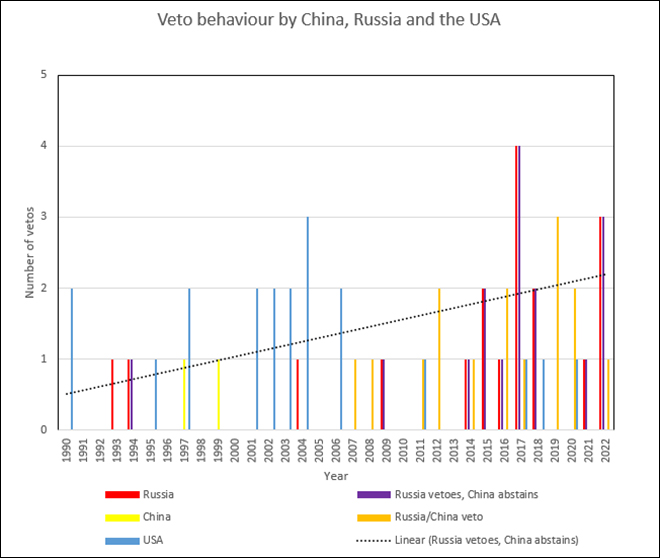

China and Russia advocate a conservative and statist interpretation of non-interference within the UNSC. Their normative collaboration is characterised by a convergence rooted in shared principles, worldviews, and threat perceptions. The voting behaviour of China and Russia within the UNSC, since 2007, illustrates an increasing degree of coordination between the two nations.[9]

The position of Russia within the UNSC as well as the UN umbrella of institutions has experienced a significant transformation following the commencement of its full-scale war against Ukraine on 24 February 2022.[10] Earlier in 2015, Russia had utilised its veto power in the UNSC to block a Western resolution condemning the annexation of Ukrainian territory.[11] On 25 February 2022, the UNSC dismissed a draft resolution, proposed by Albania and the US, which sought to terminate Russia’s military offensive against Ukraine. The draft secured support from 11 members but faced a veto by Russia, while China, India, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) abstained from voting.[12] The draft aimed to denounce Russia’s aggression as a violation of Article 2, paragraph 4 of the UN Charter and demanded its immediate withdrawal of all military forces from Ukrainian territory. China has frequently demonstrated compliance with Russian vetoes through abstention.[c]

The unsuccessful attempt to pass the draft resolution underscores the difficulties in achieving a durable diplomatic resolution to an ongoing conflict when a permanent member is directly implicated. Russia’s veto power hampers the adoption of resolutions that criticise its actions, and the abstentions by China, India, and the UAE indicate a lack of consensus among the Council’s members. The draft resolution sought to reinforce the principles of sovereignty, territorial integrity, and international law; however, its failure to pass conveys a message that these principles can be contested without repercussions.

Empirical data from the UN reveals a distinct correlation in the voting behaviour of the Russian Federation and China within the UNSC. Both nations have frequently employed vetoes on various subjects, often in synchrony. Their shared interests and analogous positions on specific international matters have fostered a pattern of collaboration and mutual backing in the UNSC. For example, Russia and China have consistently exercised their veto power in relation to the Middle East, especially concerning the Syrian war. They have jointly vetoed numerous resolutions on this issue. Furthermore, they have also cast coordinated negative votes on other occasions, such as the situations in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Iran, and Libya.[13]

Between 2008 and 2018, the UNSC adopted 657 resolutions, of which 601 (91.5%) were unanimously approved.[14] A total of 35 vetoes by Russia, China, and Russia-China were issued between 1990 and 2022 (in comparison, the US imposed 20 vetoes within the same timeframe), with the highest number of vetoes occurring in 2017, 2019, and 2022 (Figure 1).[15] Russia and China account for the majority of these vetoes, often submitting counter-draft resolutions that are subsequently vetoed by other permanent and elected members. Furthermore, the Dragonbear has been the leading source of abstention of votes in the UNSC. Moreover, China has abstained in almost all cases of Russian veto.

Figure 1: Veto behaviour by China, Russia, and the US within UNSC

Source: Author’s own research

A vastly changing geopolitical environment

Meanwhile, China continues to position itself as a powerbroker, mediating Iran-Saudi rapprochement, unveiling a Twelve-Point Peace Plan in Ukraine, and hosting Belarusian President Lukashenko, Brazilian President Lula and French President Macron.[16] As Russia becomes more isolated from the West, China is likely to further assume the role of mediator in peace efforts in Ukraine. Russia is currently facing the most comprehensive Western sanctions, while President Putin once again is relying on China to provide the main lifeline and key defence-technological cooperation to sustain the war of attrition against Ukraine. Putin’s gamble on China has so far proven correct, and a Russian victory in Ukraine would serve China’s interests in simultaneously confronting the US on two fronts in the upcoming systemic conflict.[17]

The West’s response has been to portray Russia as China’s junior partner. Should however Russia subjugate Ukraine and dismantle the European security order of the past thirty years, this dynamic may turn Europe into a geopolitical backyard of global affairs. We are now witnessing a Cold War 2.0[18] between the West and the DragonBear, which could escalate into a proxy war if China decides to provide military aid to Russia on an industrial scale.

India’s positioning as a leader of the G20 and the Global South

During the upcoming months, numerous multilateral meetings are scheduled, with the G20 summit highlighting India’s growing diplomatic role in global affairs. Given the collected data and empirical evidence, India must remain vigilant of the modus vivendi of coordination between China and Russia concerning common positions and actions within leading institutions. Both countries have already blocked a joint declaration at the G20 Foreign Ministers Meeting in Delhi, so India should be mindful of their sensitivities regarding topics such as Ukraine and Taiwan.

However, there is an upside to the modus vivendi of coordination between China and Russia as well. The possibility of resolving hostilities in Iraq, Yemen, Lebanon, and other proxy conflicts has become more realistic with China’s engagement in the Middle East. Following the Saudi-Iran agreement, the normalisation of relations between Syria and Saudi Arabia as well as the settlement of Saudi-Yemen conflict seem more realistic than before. This development signifies the rise of Chinese influence and the simultaneous decline of Western influence in Western Asia with diplomatic spill-over effects towards other regions.

Chinese leader Xi Jinping’s first international visit to Moscow, immediately after consolidating power at home, demonstrated his reaffirmed close and personal relationship with Putin. Both countries emphasised their support for the “no limits” friendship from the previous year, despite Russia’s war against Ukraine, and embarked on a “new era” of comprehensive ties that will be “a role model for major power relations.”[19] They also noted the need to prevent multipolar organisations from becoming polarised, indicating that the current deadlock at the G20 may persist and that they may project their UNSC modus vivendi of coordination onto the G20.

India is also hosting the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) summit in July, with Saudi Arabia moving towards membership, while Iran, another SCO member, participated in naval drills with China and Russia in the Gulf of Oman. The strengthening of China-Russia ties is detrimental to India’s interests, given that the former is a traditional partner, and the latter is a traditional foe. This new front will make reaching consensus at G20 more challenging and complicated, necessitating further diplomatic manoeuvring. Moreover, the International Criminal Court’s warrant for Putin does not directly affect India, as it is not a signatory, but hosting Putin in September could create an image problem.

India’s diplomatic manoeuvres can be understood as part of a balancing act, aimed at preserving its strategic autonomy while avoiding alignment with any single power bloc. By engaging with multiple power centres, such as Russia, China, the US, and the Quad members, India seeks to protect its national interests, which include maintaining regional stability, enhancing economic growth, and ensuring its territorial integrity.

India’s commitment to maintaining relations with Russia, despite Western sanctions, has raised concerns among the US and EU. However, both sides recognise India’s unique geopolitical position and historical ties with Russia. India has adopted a cautious approach, striving to balance its relations with Russia and the West. This is evident in the US’ decision not to impose sanctions on India for its defence deals with Russia, demonstrating an understanding of India’s position.

India’s argument for keeping Russia neutral with respect to China and countering Chinese influence in Central Asia through participation in organisations like the SCO is valid. By engaging with Russia, India can help prevent Moscow from fully aligning with Beijing, thus avoiding a further imbalance in regional power dynamics. Additionally, India’s presence in the SCO enables it to monitor and influence regional developments, mitigating the risk of the organisation becoming a solely anti-US/West platform. Through engagement in dialogue with Russia and China in external multilateral formats such as the BRICS and SCO, India seeks common ground to promote constructive cooperation on international security issues.

Navigating multiple relationships is a complex balancing act for India, but it can be viable if managed carefully. India must maintain a delicate equilibrium between its relationships with different global powers. Potential challenges include:

- India’s approach to abstaining from voting in situations when Russia exercises a veto could become increasingly problematic in the future when attention to the modus vivendi of coordination between Russia and China is diverted to more pressing issues.

- India’s defence ties with Russia could trigger US sanctions under Countering America’s Adversaries Through Sanctions Act. To avoid this, India should continue diversifying its defence suppliers and maintain open lines of communication with the US.

- India may face situations where it must choose between supporting its partners in the Quad or siding with Russia and China. To navigate this, India should remain committed to its principles of strategic autonomy and prioritise its own national interests.

- Balancing trade and investment between the West and Russia/China may become difficult if tensions escalate. India should focus on economic diversification and pursue multilateral trade agreements to mitigate risks.

By carefully navigating these challenges, India can maintain a delicate balance among its various strategic relationships and protect its national interests.

2. The G20’s Role

China and Russia have been increasingly coordinating their efforts within the UNSC to counterbalance the positions of the other three permanent members, the US, France, and the UK. Driven by the desire to avert diplomatic isolation and undermine US influence, this coordination has been achieved both within the UNSC and through the establishment of alternative multilateral structures outside the UNSC (such as the BRICS and SCO). Their voting behaviour in the UNSC reveals the escalating level of coordination between China and Russia as a balancing act against the West. Graham-Harrison et al. encapsulate this dynamic: “Russia and China are the common denominators in much of today’s geopolitics. The UN Security Council, APEC, the G20 – Russia and China are the ever-presents, a powerful pairing whose interests coincide more often than not.”[20]

The shifting global landscape presents significant challenges to the rules-based international order, and concretely, the UNSC. By adopting the policy recommendations outlined below, the risks associated with the growing “bilateralisation” of international relations and the rise of the Dragonbear could be mitigated, whilst preserving the principles of multilateralism and global peace and security.

Given the shift in UNSC voting patterns and the growing influence of the Dragonbear, it is crucial for policymakers and stakeholders at the G20 to acknowledge and understand the motivations behind Russia and China’s voting behaviour, particularly their focus on the non-interference doctrine while interpreting international law in accordance with their interests. The G20 countries should encourage transparency and accountability within the UNSC when it is their turn as non-permanent members, particularly regarding the use of vetoes and abstention votes. Moreover, they should monitor and analyse the implications of the Dragonbear’s growing influence on the UNSC and its impact on the international security landscape. India’s presence within the BRICS, SCO, and leadership role within the G20 this year give New Delhi the responsibility to act as a balancer between the West on the one hand, and China and Russia on the other. Finally, India will play a key role in this year to accommodate the diverging interests within the G20 as the DragonBear has already shown similar patterns of coordinating positions and actions within the upcoming summit.

The evolving dynamics of the China-Russia relationship hinge critically on the trajectory of the ongoing war in Ukraine, which appears poised on the brink of its next phase. As Ukraine has officially started its next counter-offensive, Russia is grappling with the domestic and military strain of what is likely the most formidable Ukrainian military operation to date. Concurrently, Ukraine is leveraging a unique diplomatic window, involving engagements with the G7 and Prime Minister Modi in Hiroshima, the Arab League, and the South African mediation initiative. The potential outcomes of this war – Russian victory, defeat, or an enduring stalemate with continued sanctions – each carry distinct implications for Russia’s geopolitical strength and its relationship with China. A victorious Russia could maintain an autonomous voice, while defeat or drawn-out stalemate could reduce Russia to a strategically weakened vassal largely beholden to China. These possibilities inevitably influence India’s approach to this geopolitical nexus. If Russia’s strategic autonomy diminishes, India’s interests in engaging with it might wane, unlike in a scenario where Russia emerges victorious and robust, maintaining the multipolarity of the region.

3. Recommendations to the G20

Fortify the rules-based international order

It is essential not only for the US and its allies, but also for the Global South, to reaffirm their commitment to the rules-based international order and collaborate to address the challenges posed by the Dragonbear. This can be accomplished through heightened diplomatic engagement and coordination among like-minded nations.

Encourage dialogue and cooperation

Foster dialogue and cooperation between the US, China, and Russia to address shared challenges and prevent further deterioration of the UNSC’s effectiveness. Potential initiatives include confidence-building measures and the establishment of working groups on specific issues such as nuclear non-proliferation, climate change, or global hunger and energy crisis.

Advocate for UNSC reform

Promote reforms within the UNSC to make it more representative, transparent, and effective. Possible measures could encompass expanding the number of permanent and non-permanent members, revising the veto power, and enhancing the decision-making process.

Reinforce alliances and partnerships

Strengthen alliances and partnerships with like-minded countries to collectively address the challenges posed by the Dragonbear and the evolving global landscape. This may entail deepening cooperation within existing alliances and exploring new partnerships with emerging powers. India’s participation in both Western and China-led organisations and institutions positions it as a key player in these efforts.

Attribution: Velina Tchakarova, “The UNSC and the Balancing Act Between the US and the ‘Dragonbear’: Lessons for the G20,” T20 Policy Brief, June 2023.

Endnote

[a] The author coined the term ‘Dragonbear’ in 2015 to point to developments indicative of the possibility of systemic coordination between China and Russia in key sectors and fields.

[b] The author defines the bifurcation of the global system as a comprehensive decoupling between the US and China encompassing all socioeconomic networks.

[c] China has abstained in almost all cases of Russian veto since 1990, see Figure 1.

[1] Velina Tchakarova, “COVID19 and the Indo-Pacific Decade,” Observer Research Foundation, July 2020.

[2] Velina Tchakarova and Sofia Satanakis, “EU – NATO Relations: Enhanced Cooperation Amidst Increased Uncertainty,” AIES Fokus 4, 2020.

[3] Alex J. Tarquinio, “The U.N. Has Turned Turtle on the Ukraine War: A paralyzed Security Council and a toothless General Assembly can’t come to grips with Russia’s challenge to the international order,” Foreign Policy, March 2023.

[4] Lo Bobo, “Global Order in the Shadow of the Coronavirus: China, Russia, and the West,” Lowy Institute, 2020.

[5] Deep Pal and Vir Sing, “Multilateralism With Chinese Characteristics: Bringing in the Hub-and-Spoke,” The Diplomat, 2020.

[6] Raphael Cohen, “Ukraine and the New Two War Construct” War on the Rocks, January 5.

[7] Velina Tchakarova, “The Dragonbear: An Axis of Convenience or a New Mode of Shaping the Global System?” The Institute for Development and International Relations, May 14, 2020.

[8] Gardiner Harris, “Trump Administration Withdraws U.S. From U.N. Human Rights Council,” The New York Times, June 19, 2018.

[9] Dag Hammarskjöld Library, “Security Council – Veto List (in reverse chronological order),” United Nations 2022.

[10] UN News, “The UN and the war in Ukraine: key information“.

[11] UN Security Council, “7498th meeting,” July 29, 2015.

[12] UN Security Council, “9143rd meeting,” September 30, 2022.

[13] Dag Hammarskjöld Library, “Security Council – Veto List (in reverse chronological order)”.

[14] United Nations,”Highlights of Security Council Practice 2018,” 2018.

[15] Dag Hammarskjöld Library, “Security Council – Veto List (in reverse chronological order)”.

[16] Jo Inge Bekkevold, “China’s ‘Peace Plan’ for Ukraine Isn’t About Peace: Beijing’s diplomatic overture has three ulterior motives.” Foreign Policy, April 4, 2023.

[17] Velina Tchakarova, “Enter the ‘DragonBear’: The Russia-China Partnership and What it Means for Geopolitics,” Observer Research Foundation, ORF Issue Brief No. 538, April 2022.

[18] Velina Tchakarova,”Is a Cold War 2.0 inevitable?” Raisina Debates, April 23, 2021.

[19] Xinhua, “Highlights of Xi and Putin’s talks in Russia,” State Council Information Office, March 23, 2023.

[20] Emma Graham-Harrison, Alec Luhn, Shaun Walker, Ami Sedghi, and Mark Rice-Oxley ,”China and Russia: the world’s new superpower axis?” The Guardian, July 7, 2015.