The theme of India’s G20 Presidency—“One Earth, One Family, One Future” spotlights LiFE (Lifestyle for Environment), both at the level of individual lifestyles as well as national development, leading to globally transformative actions that could result in a cleaner, greener, and bluer future. This theme directly echoes with the SDGs adopted by the UN member states in 2015, which was a universal call to action to end poverty, protect the planet, and improve the lives and prospects of everyone, everywhere, recognised that sustainable development cannot be achieved without access to education for broad sectors of society, including ethnic minorities. The purpose of this article is to share the experience of Georgia’s experience as a multinational and multilingual state in: a) providing access to higher education to young members of certain ethnic minority groups on the example of the state programme “1+4”. Since it is well-recognised that sustainable development cannot be achieved without access to education for broad sectors of society, including ethnic minorities.

According to the State Civic Equality and Integration Strategy 2021-2030 (Georgia, 2022) adopted by the Government of Georgia (GoG) in July 2021, the government reaffirmed the contribution of ethnic minorities to the sustainable development of the country as one of the most significant factors. However, the negative Soviet legacy—ignorance of the state language among ethnic minorities compactly living in the border areas—remains the main obstacle in the way of full integration of ethnic minorities in the state’s economic and political life. Over the last 30 years some successful reforms have been carried out in the educational system (e.g., integration into the Bologna system in 2004, development and promotion of English language learning through “Teach and Learn with Georgia” project, etc.), nevertheless “1+4” programme remains the single most successful programme for solving the problem of ethnic minority education in Georgia.

The Constitution of Georgia, the Law of Georgia on General education and the National Curriculum guarantee the right of ethnic minorities to receive full general education in their native language. However, it turned out that the negative historical legacy that the Georgian state inherited after independence—the lack of knowledge of the Georgian language in regions densely populated by the two main ethnic minorities, Armenian and Azerbaijani—not only creates barriers to consolidation of the entire population but also prevents these large minorities from receiving the higher education that is possible only in Georgian and from being fully integrated into building a sustainable economy and society. Solving the problem required exceptional efforts and a comprehensive approach from the government, not only involving strengthening the teaching of the state language, which itself is a rather long and time-consuming process but also overcoming the prejudices and resistance of both ethnic minorities and the titular people.

Therefore, in response, in 2009, the Ministry of Education and Science of Georgia (MoES) started to implement an ambitious 1+4 programme.

The idea behind the 1+4 programme is to make it easier to pass unified state exams by taking only general skills tests in their native (Azerbaijanian and Armenian) language (instead of state exams in 3 compulsory subjects), after which students have the opportunity to take a 1-year preparatory course to study the Georgian language intensively and further continue their studies at a department of their choice.

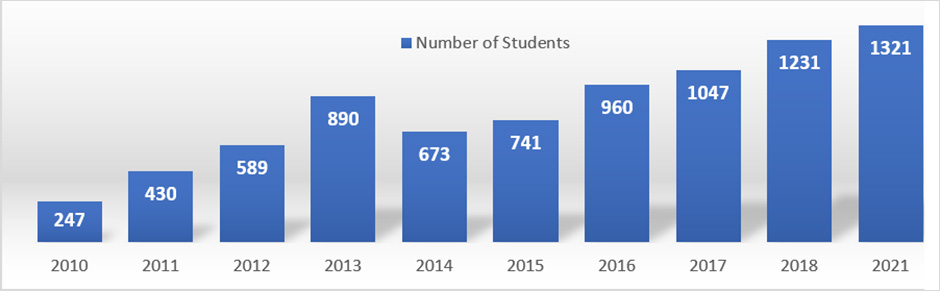

At the beginning of the incentive, only a few Azeri and Armenian minority students enrolled in the 1+4 programme. although the situation has improved significantly in subsequent years. Now annually about 1,300 students across the country use this programme to enrol in higher education. According to “A Study of Multilingual Education in Georgia” (2015), commissioned by the OSCE High Commissioner on National Minorities (HCNM), “young people from ethnic minority communities in Georgia [are also] increasingly interested in learning the Georgian language as a means of improving their socio-economic opportunities.”

Even though the number of programme beneficiaries has increased significantly since 2010, it still has room for improvement. The figures clearly show that the percentage of “1+4” beneficiaries is about 5 percent of the total student-applicant population. To compare, according to the General Population Census of Georgia (2014), 13.2 percent of the population of Georgia is ethnically non-Georgian citizens, among them Azerbaijani (6.3 percent), Armenian (4.5 percent) nationalities.

The number of enrolled non-Georgian speaking students year-wise:

As the next step, the HEIs cooperate with various state agencies to allocate vacancies for internships for students of the 1+4 programme. For example, the leading public HEI in Georgia Iv. Javakhishvili Tbilisi State University offers from one to six months of internships (a total of 500 places are provided annually) in state agencies, local self-government bodies, and legal entities of public law .

As studies show that the participation/employment of ethnic minorities in the civil service (especially at the local level) slowlyincreasing, since the start of the 1+4 programme, although it still does not fully reflect the percentage ratio with the dominant population in the respective regions.

Despite the considerable success demonstrated by the 1+4 programme—the positive impact of the programme has been noted by numerous international organizations, such as ECRI, ACFCNM, and others—based on 12 years of experience gained, it can be summarised that the main goal to be achieved and the main challenge to be addressedrequires a multifaceted approach and a simultaneous response to different types of challenges, which in turn requires additional financial and intellectual efforts on the part of government agencies. The 1+4 programme still needs to be updated and developed, tailored to the current realities and address the ongoing challenges, especially those related to developing employment policies for “1+4” graduates.

Finally, while we are referring to the Soviet legacy, althoughbe interesting to also refer to the practice of other former Soviet Republics, in this brief, we limit ourselves to an observation of the practice of the South Caucasian Republics – Georgia, Azerbaijan, and Armenia. It should be noted that in the Republic of Armenia, the issue of education for national minorities is not on the agenda, since Armenia is a mono-ethnic state; as for Azerbaijan, where historically ethnic Georgian minority lives, there is an opportunity to receive a certain amount of education in the Georgian language within the secondary school, while there is no special programme in the context of higher education.

(This essay is a part of the commentary series on G20-Think20 Task Force 3: LiFE, Resilience, and Values for Well-being )