Task Force 4: Refuelling Growth: Clean Energy and Green Transitions

Abstract

Acting on climate change and the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) requires significant investment and innovation and the right scale of finance. The world needs a new roadmap on climate finance that can mobilise the US$1 trillion per year in external finance that will be needed by 2030 in developing countries (Songwe, Stern, and Bhattacharya 2022). There is great potential and need to increase private sector investment and finance for climate. Momentum is growing among mainstream investors, driven in part by the commitment to ‘net zero’. However, cross-sectional risks impede the mobilisation of private climate finance at scale. This Policy Brief proposes a framework of solutions for the G20 to make blended finance work for the SDGs and to undertake actions in three areas: (i) enabling environments; (ii) instruments; and (iii) institutions. In doing so, the G20 can take the lead in supporting enhanced and concerted action between the public sector, private investors, Multilateral Development Banks (MDBs), and International Financial Institutions (IFIs) from both developed and developing countries to provide solutions for systemic and transaction-level constraints.

1. The Challenge

The world needs an investment push to achieve a transition to sustainability and thereby drive strong and inclusive growth and progress on the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). A focus on developing countries is required, as they account for the majority of global investment needs, particularly in infrastructure; they are also projected to account for more than three-quarters of future greenhouse gas emissions. A new roadmap on climate finance to mobilise US$1 trillion per year in external finance by 2030 in developing countries is required (Songwe, Stern, and Bhattacharya 2022).

Delivering the co-joint agenda of climate and the SDGs requires significant mobilisation and alignment of finance. The overall solution will imply mobilisation of the full array of development finance sources, including substantial increases in concessional finance. At the same time, there is broad recognition of the need to unlock private finance for investments in developing countries. For a rapid scaling up of investments, the largest increase in financing will have to come from the private sector (Songwe, Stern, and Bhattacharya 2022). Against this backdrop, expectations have been pinned on enhanced mobilisation of private climate finance through the development of finance interventions and instruments, broadly captured under the concept of ‘blended finance’.

Despite growing momentum, the required volumes of private climate finance to close the climate and SDG financing gaps far outstrips the supply. From 2016 to 2021, US$120.8 billion was mobilised from the private sector by official development finance interventions. The bulk of private climate finance mobilised—US$97.7 (representing 81 percent of the total)—targeted only climate change mitigation. US$13.7 billion (11 percent) was mobilised for adaptation, and US$9.5 billion (8 percent) for both mitigation and adaptation objectives (OECD, 2023). Furthermore, mobilised private climate finance focused on developing countries with lower-risk profiles, i.e., middle-income countries (85 percent), and economic infrastructure and services (60 percent). Only 15 percent of country-allocable mobilised private climate finance benefitted low-income countries, and 4 percent was in support of social infrastructure and services (OECD, 2023). The discrepancy between the amounts needed and supplied, especially in low-income countries, is largely explained by a set of risks and impediments which, if not managed properly, will lead to a significant escalation of the cost of capital, further hindering the mobilisation of private finance.

The end goal, therefore, of market creation and exit of public development finance should drive the approach to mobilisation for the investment push for climate and sustainable development objectives. In this regard, mobilisation alone, as a transaction-based approach, has inherent limitations. To contribute effectively to the objective it is meant to serve, mobilisation needs to be situated in a broader context of support to developing countries—notably the creation of a broader enabling environment, both through regulatory and policy measures as well as enhanced capacities, skills, and institutional development. Most importantly, the starting point for a big investment push must be strong country ownership and actions. This Policy Brief proposes an architecture of solutions to be endorsed by the G20 to overcome the underlying causes of insufficient private climate finance mobilisation in developing countries.

2. The G20’s Role

While the climate crisis is accelerating, private climate finance mobilisation is lagging behind expectations. The G20 is invited to consider a framework of solutions to make blended finance work for the SDGs and to undertake actions in three areas: (i) enabling environments, (ii) instruments, and (iii) institutions.

- Provide capacity building to developing countries to strengthen the investment climate, tackle systemic risks, and enhance the development of a pipeline of bankable projects;

- Help design risk-mitigation instruments to achieve scale, including through portfolio approaches to de-risking;

- Support multilateral development bank reform, involve the private sector, and develop emerging sustainable finance hubs into gateways to the Global South.

3. Recommendations to the G20

Developing countries: Strengthen the enabling environment and tackle systemic risks.

A significant portion of private climate finance is needed in developing countries, where the enabling environment—including real and perceived policy risks, as well as the scarcity of well-identified investment opportunities—remain key barriers to attracting capital.

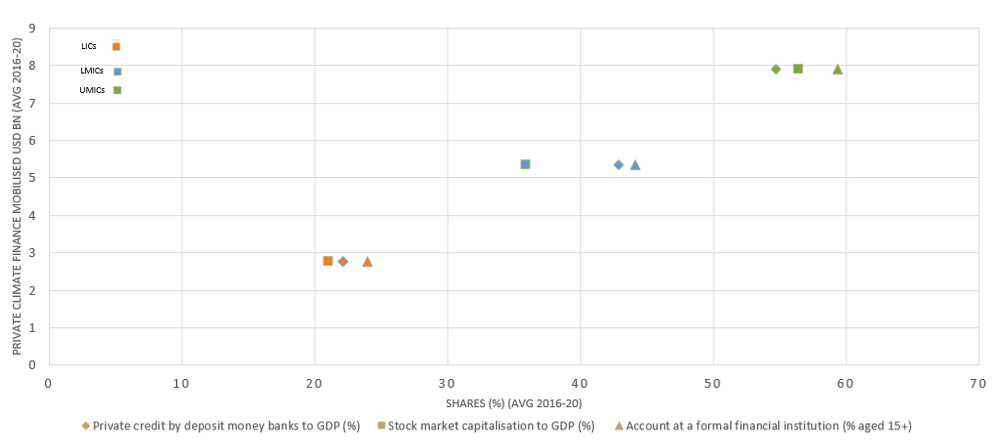

Financial development, as a fundamental dimension of the overall development process, is a key determinant of how effectively countries mobilise and allocate finances to investment needs and priorities. There is ample research stressing the importance of financial depth and access to finance (Cull and Demirgüç-Kunt 2013; Kendall 2010). Corroborating this, plotting volumes of mobilised private climate finance relative to key indicators of financial sector development consistently yields a strong positive correlation (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Mobilised private climate finance and financial sector development

Left axis: Avg. 2016–2020 private climate finance mobilised (US$ billions). Bottom axis: The depth of financial institutions is proxied by the share of private credit by deposit money banks to GDP over the period 2016–2020. The depth of financial markets is proxied by stock market capitalisation as a share of GDP over the period 2016–2020. Access to financial institutions and services is proxied by a country’s accounts at a formal financial institution (as a share of people aged 15 and more) over the period 2016–2020. Values are 2016–2020 averages.

Source: OECD data on mobilised private finance, oe.cd/mobilisation; World Bank Global Financial Development database.

Lack of financial sector development is both a symptom and a cause of the scarcity of finance. It translates to high cost of capital, which is a key feature of a country’s development status and associated financing constraints. Notwithstanding its inherent link to the overall development process, constraints that limit the scope for private financing and contribute to keeping the cost of capital high can be categorised into three dimensions: the enabling environment, intermediation, and generation of concrete investment opportunities. These can be further broken down into a number of key constraints, identified by Songwe, Stern, and Bhattacharya (2022) as:

- Weakness of investment climate, highlighting off-take risk and creditworthiness risk of key players in the energy sector.

- Exchange rate risk, which arises invariably if international finance needs to be mobilised, as local financial markets do not have the required depth to service domestic needs.

- Pipeline and associated limits to scale, where lack of sufficient high-quality investable projects and high upfront costs make initial investments non-economical, while financing volumes and liquidity profiles result in a mismatch between the way in which cross-border finance is supplied, and local demand.

- Asymmetric information on developing countries, leading to high-risk premia global private sector financiers and investors required for new, frontier markets.

- Lack of data for investors to assess risk, including through standardised taxonomies and accessibility.

- Lack of risk-mitigation instruments for risks that are unmanageable to investors.

- Mobilisation constraints, in the form of incentive structures of development finance institutions against mobilising and unlocking private investment and financing.

In the long term, the solution to scale up investment comes through sustainable economic growth and development, driven by country ownership and action, with enhanced support from international partners. In the short term, a big investment push is required to enable developing countries to maintain sustainable development and a growth trajectory. At the same time, undertaking the investments required for net-zero transitions is far more urgent (Songwe, Stern, and Bhattacharya 2022). The success and viability of such an investment push will hinge on the ability to identify systemic solutions that can strengthen the enabling environment and overcome the aforementioned constraints to private investment and financing in developing countries.

Country ownership must be at the centre of these systemic solutions. There has been increasing momentum around the establishment of country or sector platforms that bring together key stakeholders in support of country-led investment and transition strategies to foster higher ambitions around climate action and investment, with a focus on energy transition, both within the official sector (G7 and G20) and the private sector,[a] such as the Just Energy Transition Partnership model.[b] Such platforms can incentivise a country to set out clear strategies and investment programmes, tackle policy impediments, put in place structures for scaling up project preparation, and create replicable and scalable models of financing.

Tackling systemic constraints calls for more concerted action to generate common direction and momentum and scale systemic solutions. The assets, capacities, and resources of international public development finance providers, together with the private sector and philanthropic organisations, can muster solutions to overcome systemic constraints. Aligning behind a common effort and approach magnifies the scope for overcoming systemic bottlenecks and unlocking market creation through solutions for key priorities such as enhanced pipeline development, standardisation of data and project features for improved cost-effectiveness and scalability, systemic risk mitigation solutions at scale to tackle foreign exchange risk and policy risk, and moving blended finance from a transaction to a portfolio approach (Songwe, Stern, and Bhattacharya, 2022).

Instruments: Deploy blended finance more strategically and develop risk-mitigation solutions at scale.

When engaging in developing countries’ markets, the private sector often faces several transaction and systemic risks, such as exchange rate risks, policy risks, and intermediation costs which, if not managed properly, will raise capital costs significantly (OECD, 2023). To better manage these risks, investors need to gain access to fit-for-purpose and simple risk-mitigation instruments. Blended finance solutions such as development guarantees, insurance, and hedging provided by donor agencies and development banks can be used to mitigate these risks and improve the credit rating of a project.

Blended finance has been broadly defined as the strategic use of development finance for the mobilisation of additional finance towards sustainable development in developing countries (OECD 2018). It can play a key role in unlocking and financing climate investments given the risks and the long-term nature of returns. So far, however, efforts have not yielded the expected and required trajectory or increases. In 2021, only US$1.9 billion, or 1.2 percent of Official Development Assistance (ODA), were directed towards development-oriented private-sector instrument vehicles or blended finance instruments (OECD 2022).

By deploying development finance in a way that addresses investment barriers and improves the risk-return profile of investments, blended finance operates as a market-building instrument that helps attract commercial finance for climate and development (OECD, 2020). Situating transaction-level mobilisation within a broader context of catalysing private finance flows through more systemic solutions towards climate and other SDG uses in developing countries is a central principle of good practice for blended finance (OECD DAC 2017; OECD 2018). Potential solutions to improve the strategic use of blended finance include building on successful models and initiatives, scaling up portfolio approaches, aiming for both impact and volume, strengthening governance to ensure value for money, and tackling the public-private culture gap (Songwe, Stern, and Bhattacharya 2022).

Balancing risk allocation in blended finance can be achieved through scaling up portfolio approaches. The IFC Managed Co-Lending Portfolio Program (MCPP) and the proposed Global Clean Investment Risk Mitigation Mechanism (GCI-RMM) are examples of replicable structures that adopt a portfolio approach to mobilise new sources of capital for sustainable infrastructure. Successfully implemented structures (e.g., MCPP) benefit from identifying a clear and precise problem, securing the commitment of an asset owner/manager to tackle it by allocating internal resources, mobilising seed money, and developing a solution that can be replicated by other investors (Songwe, Stern, and Bhattacharya 2022). New proposals (e.g., GCI-RMM) could help lower the cost of risk mitigation by collectively de-risking large, geographically diversified project portfolios (Ghosh and Harihar 2021).

There is great potential to smoothen the public-private culture gap and accelerate the implementation of risk-mitigation solutions through knowledge sharing, as the Blended Finance Taskforce has sought to do over the last few years (Songwe, Stern, and Bhattacharya 2022). Accordingly, the Egypt COP27 presidency-mandated Sharm El-Sheikh Guidebook for Just Financing is a good example of a successful multi-stakeholder initiative that intends to capture opportunities to leverage and catalyse finance and investments to support the climate agenda (Egypt Ministry of International Co-operation 2022).

Institutions: Support the reform of development banking, involve the private sector, and facilitate the transition of emerging sustainable finance hubs into gateways to the Global South.

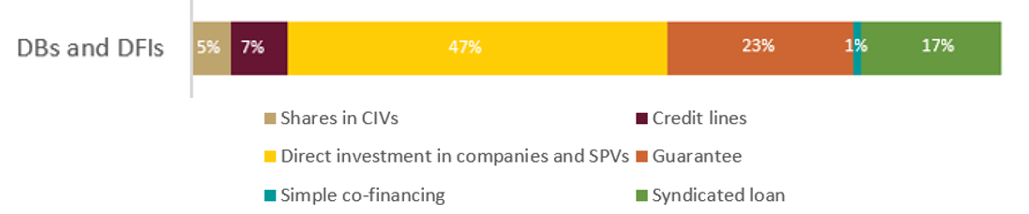

Mobilising private finance has typically fallen to the private sector arms of multilateral development banks (MDBs) and development finance institutions (DFIs) which, alongside ODA providers, develop the projects, portfolios, and ultimately, the SDG markets to crowd in commercial capital. As they understand both risk and development, these institutions benefit from structures, instruments, and skills that allow them to engage in financial transactions with varying levels of risk and returns. Besides, many MDBs and DFIs have a credit rating that allows them enhanced fundraising and credit support. Yet, MDBs remain insufficiently focused on mobilisation and their incentive structures create a risk of ‘crowding out’ private capital instead of driving co-investment and mobilisation of additional private capital (Songwe, Stern, and Bhattacharya 2022). This pattern is even more striking when considering the leveraging mechanisms used by MDBs and DFIs to mobilise private climate finance (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Leveraging Mechanisms Used by MDBs and DFIs to Mobilise Private Climate Finance (2016-2021)

2016–2021 average. Leveraging mechanisms are shares (in percentage) of total mobilised private climate finance. OECD data on mobilised private climate finance are collected for the following instruments: syndicated loans, guarantees, shares in collective investment vehicles, direct investment in companies, credit lines, project finance, and simple co-financing arrangements. The methodologies for reporting on amounts mobilised are defined by instrument (OECD, 2020), based on the principles of causality and pro-rated attribution.

Source: OECD data on mobilised private finance, oe.cd/mobilization

From 2016 to 2021, MDBs and DFIs mobilised 85 percent of the total climate finance mobilised from the private sector through official development interventions. While being critical actors in the ecosystem, over half of their mobilisation came from direct investment in companies and SPVs (47 percent), followed by guarantees (23 percent) and syndicated loans (17 percent). Conversely, they hardly made use of simple co-financing (1 percent) or shares in CIVs (5 percent) (OECD, 2023). The low share of co-financing is noteworthy, given that these institutions would appear most naturally suited to co-finance alongside private financial institutions, with relatively clear scope for synergies and complementarity. Together with their high share of direct financing, it may point to continued constraints to operations or institutional incentives to go beyond traditional approaches in enhancing a focus on mobilisation (OECD, 2023).

The ongoing reform discussion of the international development finance system has revealed a growing recognition of the need for a change in the mandate, operating models, and scale and mix of financial support required from MDBs to enable them to respond to current pressing global and development challenges, including climate change. Research points to three main areas of action for both institutions and their shareholders to fully tap into the potential of MDBs and DFIs to mobilise private capital, including for climate action (OECD, World Bank, and UN Environment 2018; OECD 2021).

First, broaden the use of development banking. To date, direct financing is at the core of development banks’ business model. Conversely, blended finance approaches to mobilise private resources for development are a small part of development banks’ financing toolkits (OECD, 2021). Second, support stronger focus on mobilising additional private finance. Shareholders need to back development banks and DFIs to focus their institutional objectives on crowding-in new investors and sources of finance to climate investments. This, in turn, will facilitate the development of future-proof markets and country-owned catalytic activities such as domestic resource mobilisation. Such a shift of business models towards additional mobilisation calls for shareholders to reduce their expectations for Return on Equity (ROE) and to rethink their allocation of concessional resources (OECD 2023). Third, target performance indicators towards mobilisation and impact. Integrating mobilisation indicators in corporate scorecards and considerations of the career advancement paths of individual officers will be key to aligning incentive systems with mobilisation objectives.

To close the climate and SDG financing gap, the reform of the financial architecture for development must go beyond MDBs and DFIs and involve private stakeholders. Several private-sector led initiatives have been launched to scale up finance for sustainable investments in developing countries. For example, the Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net-Zero (GFANZ), the Sustainable Markets Initiative (SMI), and the Global Investors for Sustainable Development Alliance (GISD) provide frameworks and platforms for private sector commitment and action. Likewise, asset owners and other stakeholders such as the Africa50 platform and the Amundi Green Bond Fund are among the most promising innovations to learn from when it comes to blending public and private sector funding and guarantees to mobilise institutional capital. These initiatives should work together proactively and in partnership with the MDBs and countries for the identification and development of projects and the reduction, sharing, and managing of risks to bring down the cost of capital (Songwe, Stern, and Bhattacharya 2022).

Lastly, emerging sustainable finance hubs in large developing economies, such as the GIFT IFSC in India, could play a key role in linking international capital with investment opportunities in the Global South. Developing such initiatives as conduits of capital to countries beyond their immediate jurisdictions can help bridge the gaps in the financial systems of developing countries. Thus, these initiatives should be encouraged to expand their focus beyond vanilla debt and equity to blended finance.

Attribution: Manon Fortemps et al., “The Myth of Mobilising Private Finance for Climate Action and Pivoting to Scale,” T20 Policy Brief, May 2023.

Bibliography

Cull Robert, and Demirgüç-Kunt. Banking the World: Empirical Foundations of Financial Inclusion. 2013.

Egypt Ministry of International Co-operation. Sharm El Sheikh Guidebook for Just Financing. Sharm El Sheikh, 2022.

Ghosh Arunabha, Nandini Harihar. Coordinating Global Risk Mitigation for Exponential Climate Finance. Stockolm: Global Challenges Foundation. Récupéré sur. 2021.

IEA. Financing Clean Energy Transitions in Emerging and Developing Economies. Paris: IEA, 2021.

Kendall Jake, and Nataliya Mylenko. “Measuring Financial Access around the World.” World Bank Policy Reserach Working Paper Series, 2010.

OECD. Investing in the Climate Transition: The Role of Development Banks, Development Finance Institutions and their Shareholders. Paris: OECD Publishing, 2021.

OECD. Making Private Finance Work for the SDGs. Paris: OECD Publishing, 2022. Making private finance work for the SDGs (oecd.org)

OECD. Making Blended Finance Work for the Sustainable Development Goals. Paris: OECD Publishing, 2018. doi:10.1787/9789264288768-en.

OECD. OECD DAC Blended Finance Principles. Paris: OECD Publishing, 2018.

OECD. OECD DAC BLENDED FINANCE PRINCIPLE 2 Guidance, 2020.

OECD. Private Finance Mobilised by Official Development Finance Interventions. Paris: OECD Publishing, 2023.

OECD DAC. Blended Finance Principles for Unlocking Commercial Finance for the SDGs, Annex to the DAC High Level Communiqué of 31 October 2017. Paris, 2017.

OECD, World Bank, and UN Environment. Financing Climate Futures: Rethinking Infrastructure. Paris: OECD Publishing, 2018.

Songwe Vera, Stern Nicholas, and Bhattacharya Amar. Finance for Climate Action: Scaling Up Investment for Climate and Development. London: LSE, 2022.

World Bank. Global Financial Development Database. 2022.

[a] See, for example, the call by Mark Carney, UN Special Envoy on Climate Action and Financing, to use enhanced country platforms to mobilise private finance at scale for developing countries.

[b] Just Energy Transition Partnerships have been established between donor countries comprising France, Germany, the UK, US, the EU, and beneficiaries which include South Africa, Indonesia, Senegal, and Vietnam.