Task Force 5: Purpose & Performance: Reassessing the Global Financial Order

1. The Challenge

Limited private finance flowing to green infrastructure and regional disparities are holding the world back from meeting global climate targets and driving sustainable development.

Over the last few years, the COVID-19 pandemic, the war in Ukraine, and the tightening of global financial conditions have complicated an already challenging financial outlook for many EMDEs. These events threaten to cut off such markets from many key financial pathways and jeopardise financing for important development outcomes that are often linked with investment in green infrastructure. Making the global financial architecture work for green infrastructure investment in EMDEs should be an urgent priority of the G20.

Building on over 17 years with some of the largest long-term private investors in the world on mobilising funding for green infrastructure, it is clear that the bankability of deal flow is one of the key issues to scaling flows of climate finance. The authors of this Policy Brief consulted with organisations including GFANZ, GFI, the Global Infrastructure Hub, members of the Independent High-Level Expert Group on Climate Finance, the Impact Investing Taskforce and the Blended Finance Taskforce, and offer a framework to create a new highway for private financial flows into EMDEs.

These recommendations aim to help implement key action tracks identified laid out by Songwe-Stern-Bhattacharya in ‘Finance for Climate Action’ launched at COP27 in 2022.[1] The report highlights the challenge thus: “Emerging markets and developing countries other than China will need to spend around $1 trillion per year by 2025 (4.1% of GDP compared with 2.2% in 2019) and around $2.4 trillion per year by 2030 (6.5% of GDP)” on transforming the energy system, responding to the increasing vulnerability of developing countries to climate impacts, and investing in sustainable agriculture and restoration of ecosystems and biodiversity.[2] However, there is a significant gap in the amount of climate finance investments as the global total was US$1.62 trillion in 2022 according to the International Energy Agency, well short of the US$4.3 trillion required annually by 2030 to meet globally shared climate objectives as projected by Climate Policy Initiative.[3],[4]

The regional disparities in the flows of climate finance are also concerning as “more than 90% of the increase in clean energy investment since 2021 has taken place in advanced economies and China.”[5] There is a particularly acute shortfall of private climate finance outside of China and advanced economies in Western Europe and North America. Increasing capital for EMDEs is particularly important to prevent lock-in of carbon-intensive infrastructure that will be a source of both future emissions growth and transitional risk going forward. In contrast, transformative investments in clean energy systems will power growth and development.

Much of the capital required for green infrastructure that will keep the 1.5 degrees Celsius goal alive can come from private sources into sectors that are investable, or soon will be. However, this private capital is not moving fast enough nor at the scale required. Over the course of the decade from 2011-2020, “The growth rate of private climate finance was slower (4.8%) than that of the public sector (9.1%) and must increase rapidly at scale.”[6] This is due to certain well-documented challenges including a poorly understood set of investment opportunities in EMDEs, a lack of pipeline and a range of project- and country-specific risks which increase the cost of capital and raise the transaction costs of doing business. In part, this is also because risk and perceived risk in EMDEs disqualifies many investors (including asset owners with vast pools of capital), and this needs to be addressed in order to unlock the trillions of dollars of investment required. Mobilising private finance in EMDEs is also likely to become more difficult in the next few years due to the increasingly challenging macro-economic environment, with monetary policy tightening, leading to a reversal of financial flows back to rich markets and risks of debt distress in several EMDEs.

Fortunately, there is existing good work that seeks to drive real progress to develop and align stakeholders around a clear roadmap to overcome the challenges and unlock large volumes of climate/transition finance in EMDEs. This roadmap is set out in the Songwe-Stern-Bhattacharya Report launched at COP27. Multiple organisations and initiatives are working on different parts of this roadmap, including revamping the role of multilateral development banks (MDBs) as major lenders to EMDEs and tackling debt and liquidity issues faced by many of these countries.

2. The G20’s Role

The transition to a low-carbon and more inclusive global economy is both urgent and investable. Mobilising capital at the speed and scale required – especially in emerging markets – will require a coordinated and strategic plan of action led by the G20 to build a new highway to unlock private investment. Aligning around a clear narrative and priorities to manage risk, reduce the cost of capital, build high-quality pipeline and empower the right stakeholders will be critical to leveraging the growing momentum and activating leadership in 2023. This will mean utilising critical platforms including India’s G20 Presidency, COP28, the Bridgetown Agenda (Macron/Mottley Summit), the World Bank’s Annual Meetings, UNGA/Climate Week, ASEAN and other key convenings of public, private and philanthropic leaders.

The G20 has an especially important role to play as this group represents 85 percent of the global GDP and nearly two-thirds of the world’s population, and produces 80 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions. With the largest source of both wealth and emissions on the planet, it is incumbent upon the G20 to use its processes and resources towards addressing climate change. Over the last few years, G20 countries have increasingly mainstreamed climate change into the group’s agenda. For instance, in 2022, the Sustainable Finance Working Group and the Bali Declaration emphasised G20 countries’ commitment to supporting developing countries in mobilising climate finance. Under the Indonesian G20 Presidency, the Global Blended Finance Task Force outlined how blended finance can play a “pathfinder role” in bringing commercial capital into sectors and regions where the financing needs are the largest, and how the global financial architecture might optimise incentives and instruments towards increasing private investments in EMDEs.[7]

The Indian G20 Presidency can build off the momentum of previous G20 summits and shape the path forward on critical sustainable finance priorities amongst other global issues. Recognising the unique nature of this geopolitical moment and the urgent imperative to bridge global climate finance gaps, this Policy Brief highlights the need for integrated de-risking processes through and in relation to existing regional financial institutions. This could also be achieved through a purpose-built institution to promote de-risking — the creation of the Green Development and Investment Accelerator (GDIA) would streamline the flow of bankable projects by serving as a global institution to support country-specific de-risking initiatives and scale best practices globally.

Ongoing feedback and experience working with institutional investor initiatives clearly supports the need for an accelerator to help develop pipeline and more effectively channel de-risking capital by reducing transaction costs and building capacity. The GDIA will create one coherent hub that leverages and binds together individual de-risking initiatives in fragmented networks of actors working in different sectors and countries to develop and accelerate actual projects in large-scale decarbonisation infrastructure around the world. These processes can also be embedded in MDBs, DFIs, INGOs and other such institutions. While many of these institutions have de-risking processes, these could be conducted in more systematic ways through the trilateral process involving finance, governments and the private sector. This could make a significant contribution in accelerating these processes independently.

The idea would be to accelerate de-risking processes at the global scale in specific sectors and geographies. For instance, after three years of working on the zero-emissions mobility financing challenge, a large collaborative[a] launched the Collective for Clean Transport Finance (CCTF) at COP27. The CCTF, incubated by the World Business Council for Sustainable Development,[b] is aiming to reach the scale and address risks in order to attract private finance to large-scale clean transport projects.

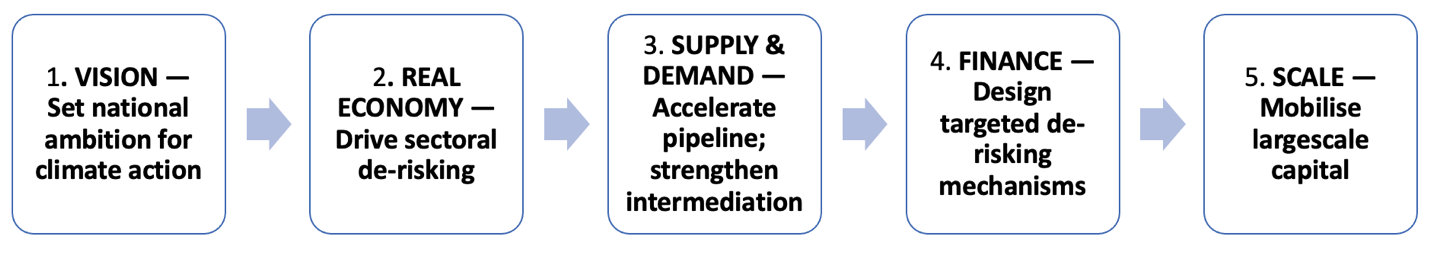

This Policy Brief proposes to complete the design for the GDIA and launch it at the G20. With the Songwe-Stern-Bhattacharya report as its intellectual pillar, the GDIA would use the following framework for action:

- VISION — Set national ambitions for climate action: Provide a clear signal for markets of policy direction; institutionalise strategic targets for action across key domestic and international stakeholders via interaction with the stakeholders.

- REAL ECONOMY — Drive sectoral de-risking: Translate economy-wide ambitions into sector-based transition planning to strengthen the enabling environment and reduce information asymmetry with investors including policy, regulation, contractual mechanisms, and data sharing. Drive multi-sectoral coordination processes involving industry, government and finance fundamentally to synchronise and de-risk individual sectors.

- SUPPLY & DEMAND — Accelerate pipeline; strengthen intermediation: Build local capacity to drive deal-flow of high-quality, transition-aligned bankable projects; leverage international expertise and scale/optimise project preparation funding; and support investor engagement and local presence to match supply and demand (e.g. through country platforms).

- FINANCE — Design targeted de-risking mechanisms: Address key risks (country, technology, currency, and customer) through efficient financial solutions including better blending of concessional and commercial capital in fit-for-purpose instruments/vehicles/platforms; optimise role of MDBs/DFIs and other contractual, policy and private sector actions to manage risk. Reducing the cost of borrowing and increasing the amount of non-sovereign lending will increase the pace of deployment of critical green infrastructure.

- SCALE — Mobilise large-scale capital: Syndicate investment opportunities to risk/return-specific pre-identified investor categories and create mechanisms that help unlock large pools of institutional investment.

Figure 1: The Green Development and Investment Accelerator’s Five-Step De-Risking Process

Source: Khemka Foundation/Blended Finance Task Force

Given the scarcity of concessional capital (concessional finance was 16 percent of total climate finance between 2011 and 2020)[8] and limited fiscal capacity of governments, a series of de-risking processes will enable more efficient use of capital. Such de-risking processes could use limited blended solutions for residual de-risking (stage 4 of the 5-step process) rather than earlier in the process. This strategy will require less units of concessional capital for investments in large-scale green infrastructure.

Working with the Global Blended Finance Alliance launched under the Indonesian G20 Presidency, the GDIA would create one coherent hub that leverages and binds together individual De-risking Centres in fragmented networks of actors working in different sectors and countries to develop and accelerate actual projects in large-scale decarbonisation infrastructure around the world.

3. Recommendations to the G20

Based on this analysis and the global imperative to accelerate the pace and scale of investments in climate action (especially mitigation-focused green infrastructure), this Policy Brief offers the following actionable recommendations to the G20:

Institutionalising the GDIA: The G20 countries could institutionalise the GDIA as a global institution that coordinates processes to reduce the transaction costs of designing and accessing risk-sharing instruments and catalytic capital – effectively becoming a hub for domestic De-Risking Centres. At the global level, the main purpose of this/these institutions would be to convene trilateral processes involving government, industry and financiers in a series of meetings to identify key challenges to the flow of capital, develop solutions to these challenges by engaging the appropriate stakeholders, and then to create the mechanisms for the syndication of this deal flow at the end of this process. At the regional and domestic level, as noted in the Songwe-Stern-Bhattacharya framework, “Country/sector platforms driven by countries can bring together key stakeholders around a purposeful strategy, scaling up investments, tackling obstacles or binding constraints, ensuring a just transition and mobilising finance, especially private finance.”[9] At the moment, no such comprehensive institutional process exists.

As such, the GDIA itself will not be a provider of capital but rather would be instrumental in reducing obstacles and friction costs to the flow of finance. Therefore, the GDIA will only require operating capital and not balance sheet capital.

Governance: The governance framework should be discussed and agreed upon by both funders and decarbonisation stakeholders in an equitable manner through the G20 process. Design principles could include:

- Thinking strategically about key decarbonisation priorities both by geography and by sector;

- Setting strategic priorities where multi-stakeholder processes, best practices, and other efforts can lead to the highest scale of potential of decarbonisation with the highest private sector capital;

- Ensuring that the ethos of the GDIA should not be of a ‘top down’ funding-style institution but rather that of a multi-stakeholder process convening, best practice sharing and facilitation organisation both at the global (especially sectoral best practice) and geographical (especially country – sectoral) levels.

Governance may be provided at two levels:

- An advisory board chosen for thought leadership and experience in this space and including representatives of G20 governments. The purpose of this board will be to set overall strategy and direction.

- A fiduciary board of directors with a strong focus on multi-sectoral representation (equal between government, private sector, civil society and long-term institutional finance). The purpose of this board will be to allocate resources correctly to allow the GDIA to play its facilitation and best practice sharing role most effectively.

Given the urgency of the climate and development challenges involved, both boards must remain nimble and meet regularly.

Location and International Structures: The physical location(s) of the GDIA may be agreed on, taking into the account the high investment expertise, convening capability and critical mass of key financial centres in the Global North and the critical importance of retaining the perspective of emerging markets in the Global South where most decarbonisation strategies and projects need to be accelerated through de-risking and funding. One idea may be to have the central organisation located in two parallel headquarters offices in G20 countries, one in a northern ‘finance hub’ and the other in a major emerging market. This would be along the lines of the ‘common but differentiated responsibilities’ of countries as recognised by the UNFCCC process.

The GDIA’s ‘best practice’ methodology: The central GDIA Secretariat would be a world-class coordination hub of best practice de-risking strategies, structures, standards, and facilities, assisting De-risking Centres that could be established in individual emerging market countries. Such De-risking Centres would be established with the support of the federal executive of the relevant country, in line with that country’s decarbonisation priorities and NDCs. (Each De-risking Centre may possibly establish an Advisory Council involving stakeholders such as planning authorities, domestic development, finance, and institutions). The GDIA would be a global hub assisting and supporting domestic De-risking Centres in a variety of possible themes often based on best practices learned from around the world:

- best practices in governmental target setting and incentive creation to decarbonisation sectors;

- contractual, policy and regulatory best practices at the sectoral level;

- coordination mechanisms and processes to crack bottlenecks across the supply chain and across multi-sectoral stakeholders in complex new sectors to enable significant scaling up;

- pipeline development best practices and resources;

- access to blended finance principals or hubs established to reduce friction costs and promote access;

- provide best practice for local deal syndication but also a global hub for such syndication.

In all cases, the local De-risking Centres would be treated as equal partners not only to benefit from the expertise of the GDIA but also to share knowledge and co-innovate. Standardisation will be balanced by localisation. For example, one of the central functions of the GDIA will be to research best practices on de-risking strategies, standards, practices and mechanisms. The GDIA will aim to contextualise world-class best practices by working with national De-risking Centres to leverage local flexibility and needs.

Coordination with MDBs, DFIs and INGOs: Both the GDIA and the local De-risking Centres would ensure thorough coordination platforms at the global and regional levels with MDBs, DFIs and INGOs. In all cases, the strategy would be to coordinate best practices and not replicate them. Such institutions are not only a source of financial de-risking support but also have considerable and rich national, sectoral and multi-stakeholder de-risking experience and expertise to share and benefit from.

Ultimately, the GDIA could play a fundamental role in addressing the key challenges to mobilising private capital in EMDEs – building on the momentum and leadership within the G20 to unlock investment for green infrastructure using fit-for-purpose de-risking tools and better project preparation. Designed and developed in partnership with EMDE leadership, there is a clear gap to be filled and the potential for outsized impact.

Attribution: Uday Khemka, Aaran Patel and Katherine Stodulka, “The Green Development and Investment Accelerator: Promoting Investable Green Infrastructure Projects,” T20 Policy Brief, June 2023.

Endnotes

[a] The Khemka Foundation, of which two authors of this Policy Brief are representatives, is a founding member of the Collective for Clean Transport Finance.

[b] Other organisations part of the Collective for Clean Transport Finance include UNEP, UITP the World Bank, the Smart Freight Centre, the ZEV-TC.

[1] Amar Bhattacharya, Vera Songwe, Nicholas Stern, “Finance for climate action: Scaling up investment for climate and development,” Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment, London School of Economics and Political Science, 2022.

[2] Bhattacharya, “Finance for climate action”

[3] International Energy Agency, “World Energy Investment 2023”, 2023.

[4] Baysa Naran, Jake Connolly, Paul Rosane, et al, “Global Landscape of Climate Finance: A Decade of Data,” Climate Policy Initiative, 2022.

[5] International Energy Agency, “World Energy Investment 2023”

[6] Naran, “Global Landscape of Climate Finance: A Decade of Data”

[7] OECD, “Tri Hita Karana Roadmap for Blended Finance: Blended Finance & Achieving the Sustainable Development Goals”.

[8] Naran, “Global Landscape of Climate Finance: A Decade of Data”

[9] Bhattacharya, “Finance for climate action”