Task Force-4: Refuelling Growth: Clean Energy and Green Transitions

The Indian government places high priority on the micro, small, and medium enterprises (MSME) sector because of its significance in alleviating poverty. Its goal is to raise the sector’s share of the GDP to 50 percent and create jobs for at least 150 million people. However, the MSME sector faces several challenges, such as supportive infrastructural gaps related to energy provisioning, especially clean energy. Limited access to credit for technology upgradation and absorptive capacity further constrain any efforts to make the transition to energy-efficient, low-carbon power sources for increased incomes. Mobilising finances from unitary sources becomes a challenge, impeding the functioning and growth of the sector. This policy brief outlines potential approaches and innovations by considering a few examples where some of the localised actions could offer insight on larger policy objectives and potentially increase alternative reliable financial support for the MSME sector.

1. The Challenge

India’s vibrant and diverse micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs) sector has been a key driver of the country’s socioeconomic growth. It has made significant contributions to the GDP, created employment opportunities in rural and peri-urban areas, and showcased India’s domestic manufacturing and services capabilities to the world. The sector accounts for about 45 percent of India’s manufacturing output, more than 40 percent of exports, over 28 percent of the GDP, and created employment for about 111 million people.[1] Several schemes and programmes, such as the Pradhan Mantri MUDRA Yojana and One District One Product, have been formulated and implemented to provide financial assistance, capacity building, and marketing support to the MSME sector.

The sector, however, is crippled with several challenges such as infrastructural gaps, delays in technological advancements, inability to compete in markets, failure to access and benefit from schemes, which results in hindering its growth. Despite their formalisation, MSMEs lack access to formal credit as banks face difficulties in credit risk assessment owing to lack of financial information and historical cash flow data. Furthermore, very few MSMEs are able to attract equity support and venture capital financing. As per the 4th MSME Census, only 5.18 percent of the units (both registered and unregistered) had availed finance through institutional sources, 2.05 percent from non-institutional sources, and the majority of units i.e., 92.77 percent had no finance or depended on self‐financing.[2]

In the era of Digital India, Atmanirbhar Bharat (self-reliant India), and near-universal electrification in the country, the reliability, adequacy, and quality of electricity supply, which is essential for seamless production in the MSMEs, is still a concern in rural and peri-urban areas. These issues affect the quality of the products produced, thus impacting the prices they can command in the market. Many micro and small enterprises turn to expensive-to-operate diesel generators and engines for power back-up. Such energy sources are not only expensive but also polluting. Therefore, there is a fervent need to strategise integrated actions to improve the income of micro-enterprises while following a low carbon pathway, which would add value and enhance their contribution to local and national economies. To achieve long-term growth and development of micro-industries, interventions must be multi-pronged and focus on promoting the use of renewable energy technology, ensuring availability of low-cost capital, developing human resource capacity, and enabling other institutional aspects.

In the post-pandemic situation, it has become even more vital to work closely with the micro enterprises facilitated by civil society, central and state government agencies, and financial institutions to ensure that:

- the assets are energy efficient and green,

- the overall productivity is not compromised, and

- the financial health of banks is not impacted due to stranded investments on technology.

Blended finance tools seem to be a plausible solution to address the demand and supply side problems of generating green finance for MSMEs to adopt sustainable and clean energy pathways. Blended finance is the use of catalytic capital from public or philanthropic sources to increase private sector investment in sustainable development.[3] Green financing mechanisms simultaneously focus on economic growth, environmental improvement, and the development of the finance industry. It utilises the intervention of public agencies in the market process to induce the flow of sufficient funds to the green economic activities, which would not happen organically in the autonomic market mechanisms.[4] Given that public funds are limited, blended finance is pivotal for the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) of clean energy transition (particularly SDG-7). Grants, technical assistance and guarantees, concessional/subordinate debt, and junior equity are widely used blended finance instruments, especially in sectors like MSMEs, which are characterised by uncertainties, high risks, foggy rewards, and no assurance.[5] There are multiple blended financing tools:

Grants: Grants are financial donations provided to entities by foundations, philanthropies, corporations, or even governments against a social developmental proposal to implement projects for the upliftment and welfare of target populations.[6] There are also returnable grants that entail zero interest loans, with a moral obligation to repay. Once returned, they could be utilised as part of a revolving fund for other programmes or priorities.[7]

Technical Assistance and Guarantees: Technical assistance is a non-monetary instrument that provides less developed countries with the expertise needed to promote developmental projects.

Guarantees share the risk associated with investing and lending in developing countries, so that private investors and development banks finance entrepreneurs or development projects. In the unlikely event of a loss, the guarantor will pay part of it.[8]

Concessional Debt: Concessional debts are below market rate finance provided by development banks and multilateral funds to developing countries for high impact projects that accelerate development objectives.[9]

Concessional blended finance: This combines concessional finance from donors or third parties and own-account finance from development finance institutions (DFIs) or other investors to develop private sector markets, address the SDGs, and mobilise private resources. It can also be considered a de-risking instrument, which is applied to reduce risks faced by project sponsors and improve risk/reward balance.[10]

Junior Equity: This instrument enables the philanthropist/funder to invest through buying a very small amount of the ownership of the project. It effectively re-structures higher risk for lower returns in exchange for social, environmental, and economic impact, typically in a position to take the first losses.[11]

Energy has been the most frequently targeted sector in blended finance transactions for the most active philanthropic investors, who have a higher risk appetite compared to private investors. For instance, they can issue concessional debt to private institutions or governments to bring down the cost of capital and improve the risk-reward ratio, making such projects more attractive to banks and private investors. It will also instill confidence in investors and financial institutions and nudge them towards funding risky but crucial projects necessary for long-term sustainable development that may not seem commercially viable today. At the same time, DFIs can either provide first-loss guarantees to absorb risk or technical know-how and assistance.

An innovative example of blended financing in MSMEs can be observed in the TERI-IKEA Foundation project ‘Sustainable energy in Micro-enterprises for Income & Livelihood Enhancement (SMILE)’. It is a case study of viability gap financing for implementing and replicating clean energy technologies in four selected MSME clusters. These clusters have been chosen using the approach of comparative advantage, where specialisation in one product is given preference. In these clusters, SMILE aims to use solar photovoltaic technology to partly ‘green’ their production processes and strengthen the reliability and availability of electricity. This will create awareness and capacity of these clusters to understand the benefits of embarking on green pathways. Currently, formal financial institutions for financing clean energy solutions in micro enterprises are scanty. Thus, the capital expenditure requirements will be co-funded by both the beneficiary and the philanthropy. The asset, however, will be owned by the beneficiary. Effective partnership is also critical at the local level and leveraging the strength of each partner must be strategic for the successful implementation of the project objectives. For this, SMILE would be creating bank and market linkages for the beneficiaries.

The concept of blended finance and comparative advantage can be applied to the context of the G20’s objectives of using green finance to bring about social impact. In developing nations like India, it will give a major boost to MSMEs. Investors in developed nations can consider green finance as a market-driven tool that factors in the environmental impact into risk assessment, or they can use environmental incentives to drive business decisions. According to the 2020 SDG Investor Map Report, rooftop solar, small 1-5 MW solar power plants) built around rural communities or MSME clusters to meet their immediate electricity demand, has been identified as a key investment opportunity area with an average return of 16 percent. In the larger context, this could contribute directly to achieving SDG-7 (Affordable and Clean Energy) and SDG-13 (Climate Action), and indirectly to other SDGs like SDG-11 (sustainable cities and communities) and SDG-12 (sustainable consumption and production).[12]

Figure 1: Benefits of Blended Finance to Various Stakeholders

Source: Authors’ own

2. The G20’s Role

As an innovative investment mechanism, blended finance offers the scope to meet the glaring funding gaps that often impair development initiatives, especially in developing nations, where government or civil society interventions may not suffice to meet developmental targets. At the same time, such financing mechanisms could be leveraged to deliver the sustainability and just transition objectives of countries, as climate action and economic development continually cease to be mutually exclusive. It is estimated that investments worth US$2.64 trillion would be required to achieve the SDGs in India, offering the private sector an opportunity to invest over US$1.12 trillion by 2030. According to the State of the Blended finance Report, the SDG financing gap which stood at US$2.5 trillion before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic went up by an additional US$1.7 trillion due to pandemic-related financing needs.[13] Developing nations prefer using blended finance as participating donor agencies with higher risk tolerance can make use of mechanisms like concessional debts to reduce the costs of development projects.[14]

The challenge, however, lies in the limited demonstrations of blended finance, especially in creating infrastructure for climate action, including energy transitions. This is even though amongst all the sectors that attract blended finance, energy is at the forefront. In addition, due to the limited scale of blended finance initiatives, participation of investors has been low, even though the developing nations of Southeast Asia, Sub-Saharan Africa, and South Asia, which are global focal points for climate action and energy transitions, are potential markets for implementing blended finance approaches.[15] Thus, the need to explore innovative mechanisms for investment in green infrastructure, such as renewable energy projects, assumes importance. Focus must be laid on making clean energy accessible to the very last mile, whether rural or urban, to meet household and productive energy needs, for an enhanced quality of life and better income and livelihood opportunities for communities. In this regard, blended finance could provide momentum to technology deployment and ensure that energy transition is expedited and just.[16] It is important to demonstrate the workability of blended finance tools in the context of community-centric distributed clean energy projects and present evidence-based cases to blended finance investors, especially private players, as it could facilitate the mobilisation of more private funding.[17]

In the case of MSMEs in India, it is established that accessing credit is one of the main challenges faced, especially by micro-enterprises, despite several supportive initiatives by the government. The instability and risks associated make them less lucrative to private investors. This is true even for other developing nations of Asia.[18]

Even with these challenges, the MSME sector showcases several positive aspects; for instance, non-performing assets among micro enterprises, though high, are still lower than other industries. Further, several new MSMEs and start-ups have emerged in recent times, making use of innovation, digitisation, and partnerships, to improve their production and services. Moreover, select Indian MSMEs, such as textiles, have a comparative advantage over their counterparts in other South Asian countries.[19] The approach of specialised clusters, also promoted by the government, provides a comparative advantage over certain products, and could be promoted to attract funding from various sources. One of the good examples of a successful cluster development is that of Italy. Promoting “competition by cooperation”, SMEs in Italy are categorised based on specialisation (of cluster activities), cooperation (among competing firms), and flexibility (in the type of production), leading to a distribution of production processes, each being operated by separate firms.[20] While developing nations could learn from these successful examples, they still must manoeuvre local challenges to achieve long-term impacts.

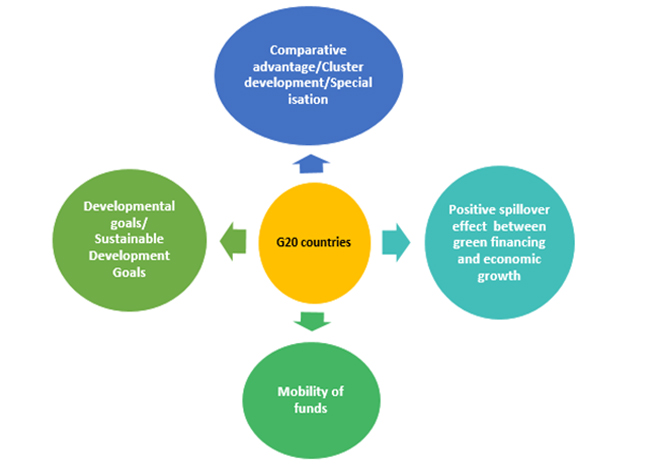

This is where the support of global institutions like the G20 could be crucial. The G20 is a body driven by the following objectives:

- policy coordination between its members to achieve global economic stability and sustainable growth,

- promotion of financial regulations that reduce risks and prevent future financial crises, and

- creation of a new international financial architecture.

The G20’s vision on sustainable growth would inevitably require financial mechanisms to ease the development journey, especially among the developing member nations, as well as to other low-income and under-developed nations globally. The G20 also recognises the financing gap for achieving SDGs and the need for innovative and blended finance mechanisms to upscale efforts. It also acknowledges the need for greater participation from the private sector, including philanthropies, to enable blended finance to achieve its full potential in reaching the last mile populations, by supporting domestic financial systems and market development.[21]

In terms of the support provided to MSMEs, financing for green infrastructure could align with the multi-faceted objectives of the various stakeholders involved. For example, provision of clean and energy efficient technologies in MSMEs could help achieve environmental objectives of the host nation, while at the micro level, it would help reduce production costs, enhance productivity, and improve income and livelihoods of the MSME actors. The potential to achieve sustainability impacts could be a justification for the financial agency, such as philanthropy or a DFI, to make the investment. Another aspect would be the evolution of various models within the ambit of blended finance. For instance, philanthropic funding directed at the development of any remote area could also be provisioned to develop partnerships with local financial agencies like banks to mobilise commercial financing for the initiative. The philanthropy backed project could also explore policy level support through credit-guarantee and such schemes of the government to contribute to the initiative to meet their own sustainability goals or venture into sustainability to support the overall national objectives. As a result, funds would be mobilised for green infrastructure and sustainable outcomes. In addition, as a spill-over effect, such blended tools would encourage domestic manufacturing in developing nations, especially when MSMEs are targeted for development. When taken up for scale, these MSMEs then contribute to the overall economic development of these countries. There is also scope for creating safety nets like distress funding for non- or underperforming MSMEs to set them on the path of success. Finally, for a successful pilot of blended finance, adequate measures could be undertaken to ensure that the beneficiary communities are equal stakeholders in these initiatives.

These aspects are being explored in the ongoing SMILE project, which represents a unique blended finance approach through a mix of philanthropic grant and community funds, while providing space for additional funding through bank financing, government schemes, and partner contributions. Similar initiatives, if taken up at much larger scales and supported by bodies like the G20, could result in developing more blended approaches in green financing, especially for distributed green energy projects. Going further, the goals of several SDGs, mainly SDG-7 (affordable and clean energy), SDG-8 (decent work and economic growth), SDG-9 (Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure), and SDG-17 (partnerships for the goals), could be achieved through initiatives supported by blended finance mechanisms.

Figure 2: Expected Outcomes from the G20’s Involvement

3. Recommendations to the G20

It is imperative for MSMEs to adopt greener technologies in their production process. However, MSMEs face enormous constraints in terms of mobilising timely and adequate finance to shift from traditional to greener technologies. This brief argues that inadequate financing options are largely a supply-side issue and there is a need to pool resources to help the MSMEs adopt new technologies. While formalisation of MSMEs is a precondition to access the formal financial sector finances, it is also pertinent to locate the sources of such formal finance. As the literature suggests, the sources of green finance could be through domestic public finance, international public finance, and private finance. In India, and other G20 countries, the support to MSMEs in providing green finance is limited except in providing some subsidies and tax rebates for adoption of green technology. However, given the scale of MSMEs, alternative sources of finance become of utmost importance.

In this regard, while MSMEs may be made to improve their ‘know your customer’ norms, from the supply side, support from the private sector as well as philanthropies need to be leveraged. In India and some other G20 countries, sovereign green bonds have been floated and the initial response to these bonds appears to be very positive. The government and its entities, those that have floated these bonds may be mandated to support the MSMEs to adopt the greener technologies which is also useful for public sector enterprises in ensuring sustainable growth.

Another way to mobilise resources could be through ‘Social Stock Exchange’.[a] Although this is new for India, it already exists in many G20 countries. These countries, as part of the G20 deliberations, need to share their best practices with other G20 countries and to countries in the Global South and encourage them to initiate such Social Stock Exchanges to mobilise specific funds from the people and entities. These funds could contribute to enhancing blended finance to the MSMEs. It is also important to understand that ensuring net-zero strategy is net-positive to all the stakeholders to enhance blended finance to needy MSMEs.

At the grassroots level, projects supported by philanthropic grants could adopt a co-funding approach from the beneficiary communities to encourage ownership and accountability. These projects could inspire and facilitate partnerships to help channelise funds from commercial banking, government agencies, and other private players. In addition, formalised processes of needs assessments, capacity building, and adequate handholding must be mandated so that the exit of the blended financial mechanism would not hamper the project’s sustainability.

Attribution: Kriti Sharma et al., “Tailoring Blended Finance to the Local Context to Support SDG-7,” T20 Policy Brief, July 2023.

[a] Social Stock Exchange is a platform that will help social enterprises raise funds from the public. It will also ensure transparency in fund mobilisation and utilisation. The Securities and Exchange Board of India has set up an advisory committee to help create the ecosystem to guide and oversee the functioning of the Social Stock Exchange.

[1] Ministry of Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises, Government of India, MSME Annual Report 2018.

[2] Chandra Sekhar Mund, “Problems of MSME Finance in India and Role of Credit Guarantee Fund Trust for Micro and Small Enterprises (CGTMSE),” IOSR Journal of Economics and Finance (IOSR-JEF) 11, no. 4, Ser. III (July – August 2020): 01-06.

[3] “Blended finance,” Convergence Finance, accessed June 14, 2023.

[4] Parvadavardini Soundarrajan and Nagarajan Vivek, “Green finance for sustainable green economic growth,” Agric.Econ – Czech 62, no. 1, (2016): 35–44.

[5] Taeun Kwon et al., “Blended Finance: When to use which instrument? Clusters and 12 key questions for decision-making,” Initiative for Blended Finance at University of Zurich, 2022.

[6] “What is a Nonprofit Grant?,” Kindful, accessed June 14, 2023.

[7] “Blended Finance – MSME Sector Supplement,” India Blended Finance Collaborative, accessed June 14, 2023.

[8] “Guarantees and blending,” European Commission, accessed June 14, 2023.

[9] “What You Need to Know about Concessional Finance for Climate Action,” World Bank, accessed June 14, 2023.

[10] Emelly Mutambatsere and Philip Schellekens, The Why and How of Blended Finance, Washington DC, International Finance Corporation, 2020,

[11] Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development and World Economic Forum, Blended Finance Vol. 1: A Primer for Development Finance and Philanthropic Funders, Cologny, OECD and WEF, 2015,

[12] UNDP India, SDG Investor Map Report for India, (Delhi: UNDP India, 2020).

[13] OECD, Making Blended Finance Work for the Sustainable Development Goals, (Paris: OECD Publishing, 2018).

[14] “Blended Finance for Climate Change Objectives,” CEEW, accessed June 14, 2023.

[15] Bella Tonkonogy et al., Blended Finance in Clean Energy: Experiences and Opportunities, (Washington DC: Climate Policy Initiative, 2018).

[16] Ben Caldecott and Rachel Kyte, “Blended finance: Unlocking renewable energy’s promise,” interview by McKinsey, McKinsey & Company Future of Asia, December 15, 2022.

[17] Bertzky, Monika, et al., The state of the evidence on blended finance for sustainable development (Bonn: German Institute for Development Evaluation, 2020).

[18] Naoyuki Yoshino and Farhad Taghizadeh-Hesary, Major Challenges Facing Small and Medium sized Enterprises in Asia and Solutions for Mitigating Them, ADBI Working Paper 564, Tokyo, Asian Development Bank Institute, 2016.

[19] “MSMEs need govt push to benefit from comparative advantage over China-made consumer goods: Report,” Economic Times, May 7, 2020.

[20] Reserve Bank of India, Report of the Expert Committee on Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises, Mumbai, RBI, 2019.

[21] G20, G20 Principles to Scale up Blended Finance in Developing Countries, including Least Developed Countries and Small Island Developing States, Bali, Indonesia, G20 Indonesia, 2022.