TF-6: Accelerating SDGs: Exploring New Pathways to the 2030 Agenda

The conversation around multidimensional gender inequalities across education, care economy, economic security, safety, and investment in social development at the G20 is key to accelerating progress towards achieving all Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and building a net-zero world. This policy brief focuses on these issues, examining the impact of COVID-19 on the lives of women and girls and gender-related SDGs. It subsequently identifies policy measures to build resilient, fair, and inclusive societies.

1. The Challenge

Education: Pandemic-induced dropouts

The multifaceted repercussions of withdrawing adolescent girls from school during lockdowns are significant. School closures in low-literacy contexts, where girls are typically inaugural learners, induce profound societal strain. Past epidemics demonstrate the heightened susceptibility of adolescent girls to discontinue education permanently.[1]

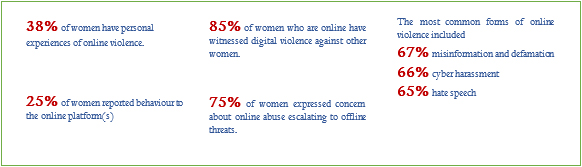

Figure 1: Interlinkages between SDG 5 and other SDGs

Source: Authors’ own

In the context of the pandemic, increased demands on unpaid and invisible care work that is foundational to households worsened gender-based inequalities. Without significant social support systems, the responsibility of unpaid care and domestic chores falls on women and girls. Pre-pandemic, women’s share in unpaid work ranged from 55.3 percent to 92 percent, with no country having achieved equal sharing of unpaid care work.[2] The International Labour Organisation (ILO) estimates that unpaid care work is amongst the most critical barriers preventing women from joining and remaining in the workforce.[3]

Unpaid care work: Have we devalued Women’s Labour?

Indian women consistently dedicate significantly more time to unpaid care work than men. Pre-COVID-19, women spent around eight times more hours on care work than men surpassing the global average of three times.[4]

Figure 2: Time spent daily in unpaid care work and paid work

Measuring unpaid care work

Time-use surveys are, till date, the best tool available to measure the amount of time spent by people within a national or sub-national region on various activities such as paid labour, education, unpaid care work, or leisure. In India, the National Statistical Organisation (NSO) conducted the first time-use survey in 2019 covering ~83,000 rural and ~53,000 urban households.[6]

Opportunity cost of women’s labour

The opportunity cost approach to women’s labour assumes that time spent on unpaid labour is at the cost of earning a market wage. Based on estimates by the ILO, unpaid care and domestic work amount to an aggregate 9 percent of global GDP, equivalent to US$11 trillion in purchasing power parity terms. This approach estimates the value of women’s unpaid work (globally) to represent 6.6 percent of GDP or US$8 trillion while men’s contribution equals 2.4 percent of GDP or US$3 trillion.[7]

Gender-based violence: The shadow pandemic

Lockdowns triggered surges in domestic violence, sexual assaults, and child abuse, especially among young girls. Gender-based violence escalated notably in areas with persistent poverty and existing violence, worsened by pandemic-induced disruptions to education, health, and social support systems.[8]

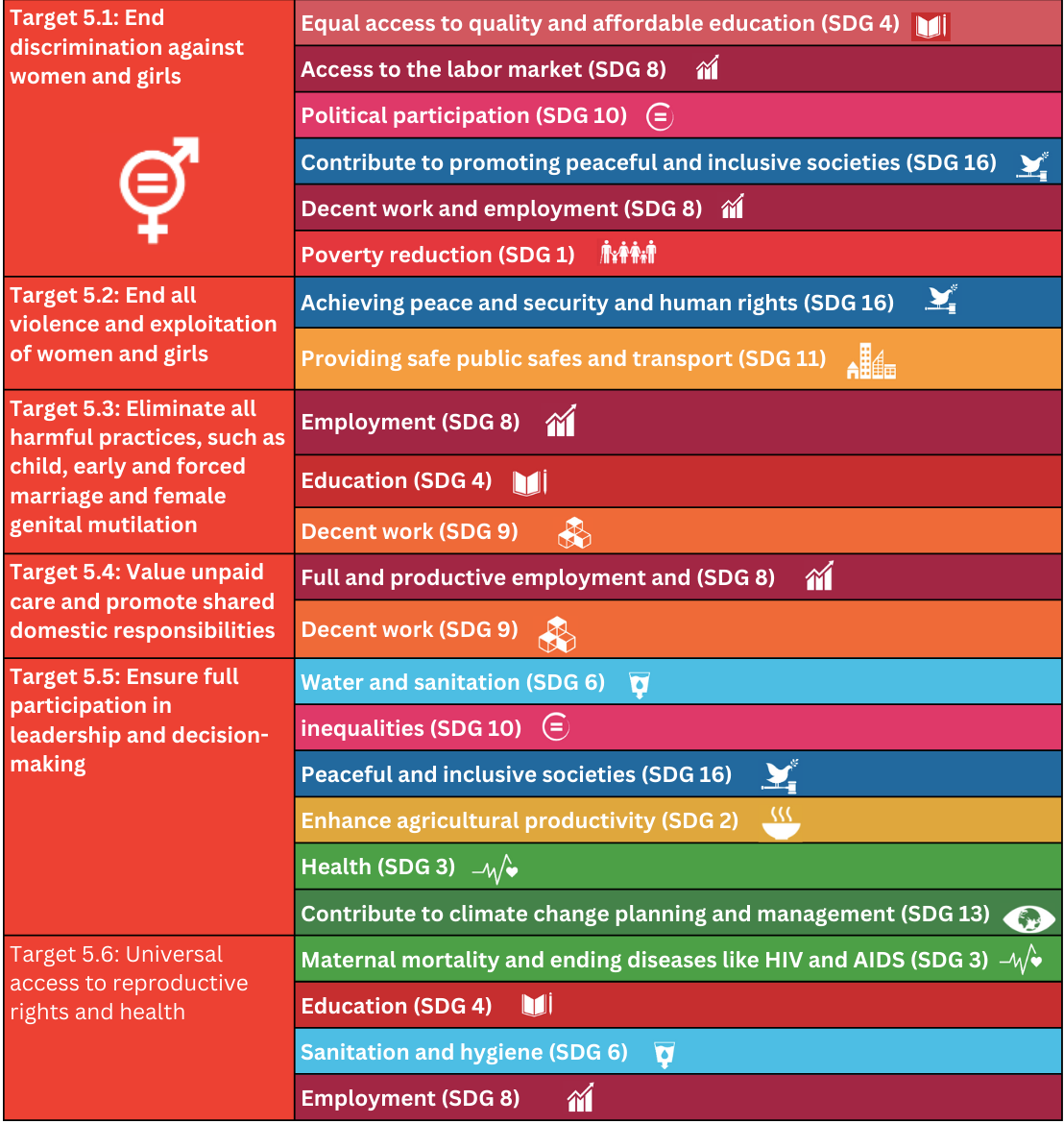

Figure 3: Gender-based violence at a glance

Source: UN Women, 2020 [9]

Poverty: Mind the gap

The pandemic intensified multidimensional poverty. Women’s employment dipped by 5 percent in 2020, far more than men which dropped by 3.9 percent.[10] 90 percent of jobless women anticipated prolonged disruption. The gender poverty gap could have widened due to resource shifts within poor households. An estimated 388 million women and girls lived on under $1.90/day in 2022.[11]

2. The G20’s Role

The 2021 Rome Declaration and 2022 Bali Declaration recognise the amplified toll the pandemic has taken on women. They’ve pledged to prioritise gender equality (SDG 5) in the G20’s pursuit of all-encompassing post-pandemic revival and enduring progress. Within this context, the G20’s guidance could propel global advancement through women-led initiatives. Research from India underscores that unpaid care work’s burden curbs women’s workforce engagement.

At the Brisbane G20 summit in 2014, a commitment was made to shrink the gender gap in workforce participation by a quarter before 2025. Progressing from this, the Women 20 group at the G20 and the second G20 Ministerial Conference on Women’s Empowerment (2022) highlighted the care economy’s challenges.

The “Women at Work in G20 Countries” paper prepared for 2023 by the ILO and the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) presents a G20 dashboard of gender gaps in labour market outcomes in 2022 and notes changes since 2012, depicting a positive change towards closing the gap in multiple job roles across G20 countries.[12]

The Government of India also planned a G20 Ministerial Conference on Women’s Empowerment[13] which was held at Gandhinagar, Gujarat from 2nd to 4th August, 2023, focusing on women-led development for accelerating progress towards gender equality, women’s empowerment, and achieving SDG 5.

3. Recommendations to the G20

Recognising, reducing, and redistributing unpaid care work; rewarding paid care work[14]

- Recognising unpaid care work: To create gender-sensitive policies, it is important to collect data on unpaid care work, which should be linked with migrant population data and labour policies to create gender and context-sensitive policies.

- Reducing unpaid care work burden: This can be done by providing services and utilities to help women, social protection to those caring for dependent populations, and care-friendly employment terms like sick leave, flexible working arrangements, and contributory social protection schemes to employed women.

- Redistribution of unpaid care to men, market, state[15]: Shift unpaid care work from women to men, as well as to other stakeholders. States and markets can offer institutional care services and prioritise investments in social infrastructure.[16]

- Rewarding paid care workers: Women are majorly employed in occupations that are usually low-paying, lack social protection, and have poor working conditions.[17] Such sectors have been ravaged by the Covid-19 pandemic, increasing risk-laden extra work and job losses. Policies should reward and respect paid care workers, establish minimum wages, define social protection, and improve working conditions for women.

Figure 4: Occupations with the largest share of women’s employment (in %)

Source: COVID-19 and the Unpaid Care Economy in Asia and the Pacific, UNESCAP, 2021[18]

Ensuring education for all

- Grasping the context-specific causes of non-participation in education is critical to formulating targeted interventions: Sub-national quantitative and qualitative surveys are important to identify reasons for low enrolment and dropouts (especially with regard to girls) from both the demand and supply perspectives of education.

Supply-side variables (inter alia) include poor infrastructure, lack of gender-segregated toilets and menstrual hygiene management tools, and cost of education.[19], [20]

Demand-side variables include restrictive socio-cultural norms, time spent on chores and care work, and performance-related factors.[21] The survey design should capture the role of pandemic-triggered factors in changing the educational trajectories of female students.

- Involving parents and community leaders in education campaigns: Education-seeking behaviour can be encouraged when parents and community leaders value education.[22] Engaging school management committees, religious and political leaders, and Parent Teacher Associations to raise community awareness about the importance of girls’ education can be an effective way to boost enrolment.[23]

Mapping out relevant stakeholders to ensure community buy-in for interventions can promote greater programmatic acceptance. - Timely identification of potential dropouts’ signals and corrective interventions can reduce drop-out rates: Signals such as long-term absenteeism,[24],[25] disengagement with learning, and repeated poor performance can be used to identify children at risk of dropping out.[26] Special learning programmes can be designed to retain them.

- Conditional incentive programmes have proved successful in attracting and retaining children, especially girls in schools: Linking incentives with attendance and performance has positively contributed to retaining girls in schools and enhancing their academic performance.[27] To encourage attendance, the cost of education could be reduced, and direct transition pathways from education to employment could be built.

- Enabling access to technology for girls has become a prerequisite for their integration into educational and employment networks: Lack of technological access has constrained girls’ access to education online, disadvantaging them and impacting future participation in labour markets. The goal of bridging the digital gender divide should be adopted in the National Action Plans on Digital Education.

Preventing and ending violence against women:

- Implementing laws and solutions to address violence against women effectively: Inadequate data hampers tracking gender-based violence and achieving gender equality. States must partner with women’s groups, follow global frameworks, reinforce laws, and provide intervention tools for eliminating violence against women.

- Addressing socio-economic stressors that may lead to violence: Food insecurity, extreme poverty, and the absence of any income source for women are risk factors that can trigger violence. These can be reduced by creating social safety nets and gender-differentiated cash transfers.[28]

- Encouraging cross-country and multi-sectoral cooperation on ending digital violence against women: Widespread digitalisation has increased cyber violence against women, which takes many forms and is connected to offline violence. Laws lack definitional clarity and consistency and fall behind technological developments.[29] Addressing this requires cooperation across countries and sectors. The G20 can encourage its member countries to establish common definitions, legal frameworks, roles, responsibilities, and standards of accountability for intermediaries.

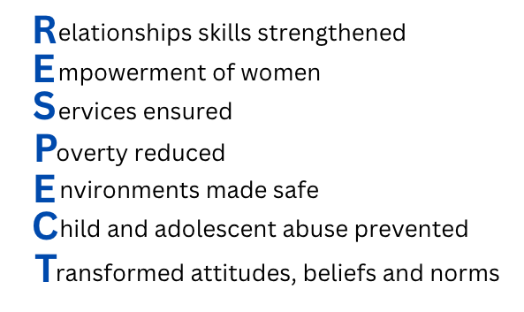

- Promoting long-term investment in transforming entrenched gender biases: To prevent violence against women, we need long-term efforts to change gender stereotypes that involve men in promoting gender equality and include gender-sensitive education. By investing in national strategic plans for gender equality and empowerment, the G20 can use the UN Women’s RESPECT Policy Framework to assess policies and implementation to address this challenge.[30]

Figure 5: Women’s RESPECT Policy Framework

Source: UN Women, 2020 [31]

Policy options for poverty alleviation among women and children

- Making laws gender-sensitive: Because over 2.4 billion women are restricted in their job choices by legalities and have inferior land, resource, and property rights, women and children are at greater risk of experiencing poverty than men.[32] If consensus can be reached on doing away with gender-biased laws in a time-bound manner, progress can be made in eliminating relative poverty for women and children.

- Providing equal opportunities for women to participate in the labour market: Completing school education, skill development, and adapting to digital technology and labour market demands can help women achieve equal participation in the labour market. This can help lift women out of poverty. Bridging the wide gender wage gap of 23 percent[33] through legislation will help improve women’s socio-economic status.

- Development of the care economy: Women tend to spend around 2.5 times more time on unpaid care and domestic work than men, which adversely impacts women’s labour force participation rate.[34] Making this care work remunerative will have a direct impact on reducing poverty.

- Introducing gender-sensitive social protection policies: Gender gaps in job access hinder women’s social security, heightening poverty and debt risks. Gender-sensitive policies are essential to countering socio-economic uncertainties.

- Providing basic infrastructure and protection from climate change and environmental degradation: Safe water and sanitation gaps disproportionately affect women. Insufficient sanitation facilities impede menstrual hygiene and hinder physical and socio-economic progress. Without social security, women and children face heightened challenges from environmental shocks, displacement, and deforestation.

Marshalling insight into action

To prioritise gender equality and empowerment, G20 leaders can create a group of women parliamentarians from G20 countries, tasking them with developing policy pathways to accelerate these goals into action. This will help bridge ‘the long road ahead’ on SDG 5.C that focuses on adopting and strengthening ‘sound policies and enforceable legislation for the promotion of gender equality’. Gender equality and care-burden-related targets are areas where the distance to attaining gender-related SDGs is farthest.[35]

G20 women parliamentarians can propose policy pathways to gender equality and empowerment

The G20 EMPOWER initiative aims to enhance women’s private sector leadership. A subgroup of women political leaders in the G20 countries can propose strategies to counter the pandemic’s socioeconomic setbacks for women. By engaging stakeholders, the group can highlight pandemic-induced gender disparities in policies and expedite pathways to global gender parity.

Addressing the acute dearth in quantity and quality of data to monitor progress on indicators related to SDG5 and all interlinked SDGs

In addition to medium to long-term recommendations, the group can recommend short-term response strategies, including quantitative and qualitative ways in which national statistical systems can collaborate with grassroots women’s organisations. It can also shed light on the intersectional data required on different vulnerable groups within the category of women.

- Developing social protection and social security policies providing coverage to women with differential needs, particularly in times of crises.[36]

- Recognising, reducing, and redistributing unpaid care loads and rewarding paid care workers.

- Assessing whether it is time to revise the right to free and compulsory primary education to include free, compulsory secondary education for all, which can be coded into the educational policies of G20 countries so that dropped-out girls can be brought back to education by law in a rights-based framework.

- Developing a framework for policies including budgets to assess where they stand on a continuum of gender-discriminatory—gender-blind—gender-neutral—gender-sensitive—gender-responsive approaches and revising policies along the spectrum on a graded basis at least or designing plans for a galloping leap if their context allows.

- Establishing innovative ways to finance the formulation and implementation of new policies that empower women on the socio-economic aspects of education, employment, preventing and addressing violence, care economy, health, and social protection.

A G20 digital platform for preventing and ending cyber violence against women

Addressing the escalating transnational, anonymous violence against women demands a targeted multinational effort. Led by G20 technology ministers, this subgroup should include technocrats, specialised women’s organisations, major tech intermediaries, and the UN. Incorporating women’s perspectives to address the gender imbalance in the Information and Communications Technology sector, the subgroup must collaboratively establish standards, laws, and solutions to combat evolving digital violence against women.

Figure 6: Digital violence against women at a glance

Employing a gender-focused approach and harnessing multidimensional strategies to address intricate cross-cutting challenges through precise yet harmonised interventions offer a promising route towards achieving not only SDG 5 but also interconnected SDGs. Within the G20 framework, prioritising interventions in the care economy, along with gender equality policies and legislation, becomes imperative, given the substantial shortfall in meeting targets (target 5.4, 5.C) within SDG 5. The urgency of combating transnational digital violence against women requires dedicated multilateral endeavours.Social protection schemes to alleviate gender inequality

Worldwide, over half the population lacks social protection, with only under 30 percent receiving comprehensive coverage.[39] Women face further setbacks in these systems, encountering reduced coverage and benefits. Factors contributing to this include flawed schemes built on male-centric models, women’s limited presence in formal job markets (coupled with overrepresentation in unprotected informal sectors), the burden of unpaid care work, and gender pay disparity.

Funding social protection schemes

SDG credits: In simple terms, SDG-based credit strategies encourage investors to invest in companies that help them achieve SDG goals. This can mean buying bonds for companies that contribute to one or more SDGs and avoiding companies that break SDG norms.

Robeco’s measurement framework for SDGs follows a three-step evaluation process- product assessment (positive/negative impact), production procedures analysis, and a study of the company’s involvement in litigations and controversies. Such frameworks enable investors to analyse corporate bonds, favouring those aligning with SDGs and excluding those conflicting with them.

SDG bonds: Bond markets provide cost-effective capital for SDG implementation. With a US$6.7 trillion global annual bond issuance, SDG bonds can help meet rising investor interest in social impact.[40] These bonds, such as corporate, bank, asset-backed, project, sovereign, or municipal SDG bonds, can help shape socially conscious investing.

Domestic fiscal measures for gendered budgeting

Domestic fiscal strategies encompass two paths: one, channelling funds for gender-sensitive social protection; and two, shaping fiscal policies that incentivise gender-equitable industries. Yet, India’s annual budget has shown inadequate gender-focused allocations, declining from 4.72 percent (FY21) to 4.4 percent (FY22) and 4.3 percent (FY23) of total expenditure.[41]

Gig economy

The World Economic Forum defines the gig economy as an “exchange of labour for money between individuals or companies via digital platforms that actively facilitate matching between providers and customers, on a short-term and payment-by-task basis.”[42] The OECD reports that globally gig workers largely experience job satisfaction, suggesting their participation is voluntary and not due to limited alternatives. In India, digital platform freelancing allures women with flexible work arrangements, reducing reliance on fixed locations, aiding in balancing paid and unpaid responsibilities.

A McKinsey study [43] categorised independent workers into four segments:

- Free agents (who choose independent work and derive their primary income from it),

- Casual earners (who use independent work by choice for supplemental income),

- Reluctant workers (who make their primary living from independent work but would prefer traditional jobs), and

- Financially strapped (who do supplemental independent work out of necessity).

Gig work, characterised by its flexibility and digital platforms, has rapidly expanded as an employment option. However, it is essential to recognise that this form of work is not without its fair share of problems. Workers engaged in gig work often face challenges such as inconsistent income, limited access to traditional employment benefits, and potential exploitation due to the absence of regulatory frameworks. Additional concerns include a lack of job security and uncertain employment status. According to a study conducted by the Observer Research Foundation and the World Economic Forum in 2018, 35 percent of surveyed women were disinterested in joining the gig economy due to similar reasons.[44]

Globally, lower- and middle-income nations witness 7 percent mobile ownership gap and 15 percent mobile internet gap between the genders.[45] These disparities in access to mobile technology can impact various aspects of the gig economy, potentially further marginalizing certain groups and hindering their participation in this evolving employment ecosystem.

The challenges posed by the pandemic present a unique chance to reshape societal dynamics towards a just, equitable, and nurturing world, where women lead development rather than passively benefitting from it. Grasping this moment is a pressing necessity.

Attribution: Nitya Mohan Khemka, Soma Das, and Suraj Kumar, “Tackling Multidimensional Gender Inequality in G20 Countries,” T20 Policy Brief, October 2023.

Endnotes

[1] Muhammad Jehangir Khan and Junaid Ahmed, “Child Education in the Time of Pandemic: Learning Loss and dDropout,” Children and Youth Services Review 127 (2021): 106065.

[2] Judith Derndorfer et al., “Home, Sweet Home? The Impact of Working from Home on the Division of Unpaid Work during the COVID-19 Lockdown,” PLOS ONE 16, no. 11 (2021): e0259580.

[3] Laura Addati et al., “Care Work and Care Jobs for the Future of Decent Work”, International Labour Organization, 2018.

[4] Mitali Nikore et al., “Building India’s Economy on the Backs of Women’s Unpaid Work: A Gendered Analysis of Time-Use Data,” Observer Research Foundation, 2022.

[5] United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific, “COVID-19 and the Unpaid Care Economy in Asia and the Pacific”, UNESCAP, 2021.

[6] Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation, “NSS Report: Time Use in India- 2019 (January – December 2019).” Press Information Bureau, 2020.

[7] Laura Addati et al., Care Work and Care Jobs for the Future of Decent Work.

[8] UN Women, “Gender-Based Violence: Women and Girls at Risk“, UN Women.

[9] UN Women, “The Shadow Pandemic: Violence against Women during COVID-19,” UN Women, 2020.

[10] International Labour Organization, “World Employment and Social Outlook: Trends, 2021”, ILO, 2021.

[11] UN Women, UNDP and Pardee Center for International Futures, “Poverty Deepens for Women and Girls”, UN Women, UNDP and Pardee Center for International Futures, 2022.

[12] International Labour Organization and Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, “Women at Work in G20 Countries: Progress and Policy Action in 2022”, ILO and OECD, 2023.

[13] Ministry of Women and Child Development, “G20 Ministerial Conference on Women’s Empowerment to Be Held at Gandhinagar, Gujarat from 2nd to 4th August, 2023,” MWCD, August 1, 2023.

[14] Diane Elson, “Recognize, Reduce, and Redistribute Unpaid Care Work: How to Close the Gender Gap,” New Labor Forum 26, no. 2, (2017), 52–61.

[15] ILO and OECD, Women at Work.

[16] Rania Antonopoulos, “The Unpaid Care Work – Paid Work Connection”, International Labour Organization, 2009.

[17] Diane Elson, Recognize, Reduce, and Redistribute Unpaid Care Work: How to Close the Gender Gap.

[18] UNESCAP, COVID-19 and the Unpaid Care Economy.

[19] Jacques Charmes, “The Unpaid Care Work and the Labour Market. An Analysis of Time Use Data Based on the Latest World Compilation of Time-Use Surveys”, International Labour Organization, 2019.

[20] Deepta Chopra and Elena Zambelli, “No Time to Rest: Women’s Lived Experiences of Balancing Paid Work and Unpaid Care Work”, Institute of Development Studies, (2017).

[21] Sunita Chugh, “Dropout in Secondary Education: A Study of Children Living in Slums of Delhi,” Semantic Scholar, (2011).

[22] Mausam Kumar Garg, Poulomi Chowdhury, and Illias Sheikh, “Determinants of School Dropouts in India: A Study through Survival Analysis Approach,” Journal of Social and Economic Development (2023).

[23] Maki Nakajima, Yoko Kijima, and Keijiro Otsuka, “Is the Learning Crisis Responsible for School Dropout? A Longitudinal Study of Andhra Pradesh, India,” International Journal of Educational Development 62 (2018).

[24] G.V JayaLakshmi, J.E Merlin Sasikala, and T. Ravichadran, “Parental Attitude Towards Girl’s Education,” RESEARCH REVIEW International Journal of Multidisciplinary 6, no. 5 (2021).

[25] Ronak Paul, Rashmi Rashmi, and Shobhit Srivastava, “Does Lack of Parental Involvement Affect School Dropout among Indian Adolescents? Evidence from a Panel Study,” PLOS ONE 16, no. 5 (2021): e0251520.

[26] Elaine Allensworth and John Q. Easton, “The On-Track Indicator as a Predictor of High School Graduation”, Chicago, UChicago Consortium on School Research, (2005).

[27] Jeanne Gubbels, Claudia E. van der Put, and Mark Assink, “Risk Factors for School Absenteeism and Dropout: A Meta-Analytic Review.” Journal of Youth and Adolescence 48, no. 9 (2019): 1637–67.

[28] Donna J. Dockery, “School Dropout Indicators, Trends, and Interventions for School Counselors,” Virginia Commonwealth University.

[29] Nobuhiko Fuwa, “The Net Impact of the Female Secondary Stipend Program in Bangladesh,” Social Science Research Network, (2006).

[30] UN Women, “RESPECT Women: Preventing Violence against Women – Implementation Package”, UN Women, 2020.

[31] UN Women, RESPECT Women: Preventing Violence against Women – Implementation Package.

[32] World Bank Group, “Women, Business and the Law 2022”, World Bank Group, 2022.

[33] UN Women, “Equal Pay for Work of Equal Value”, UN Women.

[34] International Labour Organization, “World Employment Social Outlook: Trends for Women 2017”, ILO, 2017.

[35] UN Women, “Turning Promises into Action: Gender Equality in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development”, UN Women, 2023.

[36] International Labour Organization, World Employment and Social Outlook: Trends for Women.

[37] Economist Intelligence Unit, “Measuring the Prevalence of Online Violence Against Women”, The Economist.

[38] UN Women, “Intensification of Efforts to Eliminate All Forms of Violence against Women: Report of the Secretary-General”, UN Women, 2022.

[39] International Labour Organization, “World Social Protection Report 2020–22: Regional Companion Report for Asia and the Pacific”, ILO, 2021.

[40] United Nations Global Compact, “SDG Bonds and Corporate Finance”, UN Global Compact, 2018.

[41] Mitali Nikore, “Budget 2022: Did It Deliver on #NariShakti and Women-Led Development?” SheThePeople, February 4, 2022.

[42] World Economic Forum, “The Gig Economy: What Is It, Why Is It in the Headlines and What Does the Future Hold?,” World Economic Forum, 2023.

[43] James Manyika et al., “Independent Work: Choice, Necessity, and the Gig Economy”, McKinsey Global Institute, 2016.

[44] Terri Chapman et al., “The Future of Work in India: Inclusion, Growth and Transformation: Inclusion, Growth and Transformation”, Observer Research Foundation and The World Economic Forum, 2018.

[45] Matthew Shanahan, “The Mobile Gender Gap Report 2022”, GSMA, 2022.