Abstract

For over a decade, India’s digital public infrastructure (DPI) has been harnessed for cash transfers to citizens through the Direct Benefit Transfer (DBT) programme. The DBT programme has grown exponentially since the COVID-19 pandemic. Recent studies show that in India and the developing world, government-to-person (G2P) transfers have become a significant factor in women’s adoption of financial services. Women’s decision-making powers within their homes improve due to digital G2P payments, which also has a positive impact on their employment, health, and education. But women continue to face barriers in digital access and usage, along with adverse norms, which impacts their digital financial inclusion.

Aligning with G20 priorities of financial inclusion and women’s economic empowerment, this policy brief reviews the use of digital technology in G2P payments to women in India, analyse the gaps, and draw lessons for emerging economies. It offers recommendations to the G20 to strengthen digital G2P payment programmes.

- The Challenge

In 2013, the Indian government introduced Direct Benefit Transfer (DBT), a government-to-person (G2P) payments programme for social benefits. The programme had a few stated objectives: to reduce fiscal leakages, eliminate corruption, reduce costs, and increase efficiency in the delivery of welfare. It would simultaneously accelerate financial inclusion and social empowerment through transfers made directly into citizens’ bank accounts.

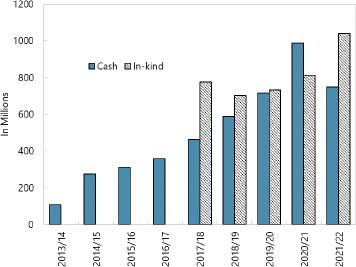

The DBT programme, which has led to savings of INR 2.73 trillion between 2013 and 2022,[1] has grown to cover nearly all welfare schemes by the government, ranging from pensions and wages, to health, education, rural development, housing, and subsidies in food, fuel, and agricultural. More than INR 6.9 trillion was transferred in 2022-23 compared to INR 3.8 trillion in 2019-20, an increase of over 80 percent in cash transfers as cash transfers became a lifeline during the COVID-19 pandemic (see Figure 1).[2] India is not alone in this; the pandemic led to the largest scale-up of cash transfers for social protection globally, which were planned or implemented in 186 countries.[3]

Figure 1: Direct Benefit Transfer Beneficiaries in India (in millions, by type)

Source: IMF Working Papers[4] and Government of India[5]

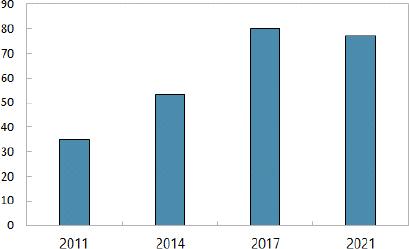

DBT has been built on the back of the robust digital public infrastructure (DPI) framework, which has helped India advance its development goals, fast-track financial inclusion, and enable efficient delivery of public services. DPI, which allows for exponential outcomes, has helped India accelerate financial inclusion by four decades (see Figure 2).

This feat can be credited to Aadhaar, the foundational building block of DPI, and the largest biometric identification programme in the world. Aadhaar is the central element of the ‘Jan Dhan, Aadhaar, and mobile’ (JAM) trinity, which integrates bank accounts (Jan Dhan) with unique identity (Aadhaar) and mobile technology to form the core structure for direct transfers.[6] Through DPI-based solutions, the gender gap in access to bank accounts has been closed and there has been considerable progress in addressing credit gaps to women entrepreneurs, by prioritising lending to women.[7]

Figure 2: Financial Inclusion in India (financial institution account %)

Source: IMF Working Paper,[8] Global Findex 2021, World Bank[9]

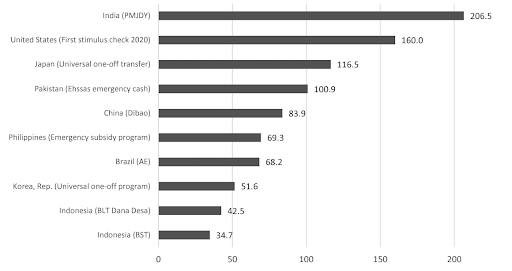

From April to June 2020, India leveraged its existing DPI to undertake the largest COVID-19-related cash transfer worldwide to 206 million female beneficiaries (see Figure 3). It demonstrated that digital cash transfers can promote macroeconomic resilience and, at the same time, cushion the impact of shock on households by providing a sound social safety net.[10]

Figure 3: Top 10 COVID-19 related cash transfer programmes in the world by actual coverage (million people)

Source: World Bank, 2021[11]

Government-to-person (G2P) payments have driven up the financial inclusion of women in developing countries worldwide. In 2021, 423 million women in developing countries opened their first account at a financial institution to receive government payments, like pensions, wages, welfare, and subsidies.[12] Receiving digital payments from the government is a catalyst for financial inclusion, and those who receive payments are more likely to save and borrow money as well.[13]

Barriers to Women’s Access

Even though India has a lead in G2P payments through a responsive and inclusive digital system, there is evidence that female beneficiaries of DBT are at greater risk of unintended exclusion.[14] This is down to the social and economic barriers that women face.

Less than 54 percent women in India own a mobile phone, a gender divide that is among the highest in the world.[15] Women are likely to lack identification and access to mobile phones, and face barriers to developing digital literacy and restrictive norms that impede their usage of mobile phones.

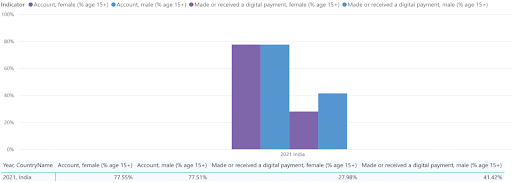

Mobile phones are critical for accessing information. Without access to digital devices, women are cut off from knowledge, employment opportunities, and networks to make full use of government benefits. A 2019 study on DBT found that women were in many cases unaware of their entitlements, the timing of disbursements, and how to use their accounts.[16] An assessment of cash transfers to women during the COVID-19 pandemic corroborates these findings. Female beneficiaries struggled to access information on transfers and access payments through cash-out facilities (like bank branches or banking agents) in conditions where women’s dependence on cash-out facilities is higher than men (see Figure 4).[17]

Figure 4: Gender Gap in Bank Account Ownership versus Digital Payments in India

Source: Global Findex 2021[18]

To address women’s exclusion, care must be taken to ensure that the programme design has a target beneficiary approach and accounts for norms that impact their digital financial inclusion, like a vast majority of women not being in paid work, more likely to work in the informal sector, to take on the burden of care work, and face mobility constraints.[19]

Source: Assam Orunodoi Scheme[20]

The G20’s Role

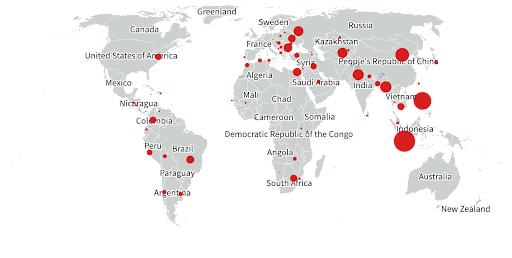

The pandemic underscored the importance of DPI in providing social assistance. It enabled governments to reach an unprecedented number of new beneficiaries, bringing them into social protection and financial systems for the first time (see Figure 5).

Figure 5: Government payments in cash to unbanked adults

Source: Global Findex 2021[21]

Note: Adults without an account received government payments in 2021 in cash only. Shifting these payments to accounts could create an entry point among the unbanked for financial inclusion.

India’s DBT programme has achieved significant success, and other countries can learn from its outcomes and challenges. The G20 can play a crucial role in the coordination among relevant stakeholders, governments, and the private sector to ensure inclusive systems worldwide for G2P payments.

Financial inclusion has been a priority for the G20. There have been multiple initiatives that have taken forward this agenda, including the Global Partnership for Financial Inclusion (GPFI), the G20 High-Level Principles for Digital Inclusion, and the G20 Financial Inclusion Action Plan 2020. The 2020 communiqué by G20 Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors supported the GPFI’s emphasis on the digital financial inclusion of women.[22] In 2022, under the Indonesian presidency, ‘closing the digital gender gap’ was discussed as a top priority at the Ministerial Conference on Women’s Empowerment. The Digital Economy Task Force was upgraded to a Digital Economy Working Group, which identified ‘digital financial inclusion’ and ‘payment system in the digital era’ as key priorities under the G20’s finance track for 2022.[23]

Women’s participation in the labour market is lower than men’s in all G20 member countries.[24] At the 2014 summit, G20 leaders pledged to reduce the gap in labour force participation rates between men and women by 25 percent by 2025. There is evidence that cash transfers into bank accounts of women improve their labour force participation, which can serve as a roadmap to the Brisbane Commitment.[25]

It is estimated that nearly 60 percent of global GDP relied on digital technologies in 2022 and this is likely to increase further, putting at risk those who are unable to participate in the digital economy, especially women.[26] Digital G2P payments are a pathway to bring women into the digital economy. Increasing women’s participation in the digital economy could potentially increase the global GDP by US$5 billion.[27]

The gender digital divide is most prevalent in low and middle-income countries. The G20 initiative #eSkills4Girls, established under the Germany presidency in 2017, aims at tackling the gender digital divide in low income and developing countries to boost education and employment opportunities for women and girls. As emerging economies hold the grouping’s presidency there is a unique opportunity for the G20 to consider a range of solutions and coordinate global efforts for investing in women’s digital financial inclusion.

Source: World Bank, December 2021; Women’s World Banking, October 2020[28]

- Recommendations to the G20

The experience with the pandemic has shown that countries with advanced DPI and payment systems are better equipped to extend social protection and enhance financial inclusion. This brief recommends putting women at the centre of digital G2P payment programmes to help countries mitigate exclusion risks, increase impact on women’s empowerment and improve social protection systems.[29] With the rapid expansion of G2P payments there is an opportunity to catalyse necessary reforms and address gender gaps through the G20, which can facilitate knowledge exchange and capacity-building of G2P payment systems for improved outcomes for women.

- Optimise the DPI approach for financial inclusion

The G20 can support a knowledge exchange platform for countries to share expertise and best practices on DPI for financial inclusion. It can foster capacity-building to improve G2P payment systems, which could encompass the development of inclusive DPI and digital payment systems, identification and targeting of beneficiaries, and data management and data protection mechanisms.

The G20 can further promote collaboration among stakeholders in G2P programmes, such as governments, financial institutions, technology and payment service providers, and civil society organisations. It can set frameworks for countries to track and measure financial inclusion through DPI. In addition, India’s MOSIP (Modular Open Source Identity Platform) and the World Bank’s Identity for Development, which are helping countries build their national digital identification systems, could encourage partner countries to create tracking mechanisms for financial inclusion in tandem with their identification programmes.

- Prioritise gender-responsive design and targeting

The G20 can encourage countries to adopt gender-responsive design and targeting in G2P payments to maximise impact on female beneficiaries with the following approaches:

- i) Collect and analyse gender-disaggregated data: The pandemic exposed the gaps in existing social registry systems. The precision with which social programmes can be targeted increases with the granularity of data that is available to governments about individuals and households.[30] The G20 can establish a common framework for data collection and support initiatives by national statistical offices and financial institutions to collect and analyse gender-disaggregated data and share anonymised data among stakeholders for evidence-based policy actions.[31]

- ii) Targeted communication and awareness campaigns: Awareness campaigns are essential for female beneficiaries who are more likely than men to lack access to information on benefits. One study in India found that 65 percent of women preferred in-person interactions to understand programme objectives and resolve queries on direct transfers.[32] The G20 can create guidelines for financial institutions and civil society organisations to improve awareness initiatives on G2P programmes.

iii) Mobilise women’s networks: Incorporating women’s collectives (such as savings groups, producer cooperatives, self-help groups, and community-based organisations) at every stage of programme implementation is an effective strategy. These groups can be mobilised for enrolling female beneficiaries, improving awareness, and for creating access to digital devices and digital literacy. These networks can also play a role in creating a feedback loop between beneficiaries and the local government.[33] The G20 can devise policies to support local governments and NGOs to create capacities for women’s groups to work on this.

- Reduce barriers for female beneficiaries

Women face tech-related and social barriers. The following approaches can be considered to resolve these issues:

- i) Facilitate universal access to mobile phones: In a paper under the Saudi Arabia presidency in 2020, the GPFI outlined policy options for the G20 to advance women’s digital financial inclusion through universal access to mobile phones.[34] However, across low- and middle-income countries, women are still seven percent less likely than men to own a mobile phone, and 15 percent less likely to use mobile internet.[35] The G20 can facilitate women’s universal ownership of mobile phones to close the mobile phone ownership gap. Governments can work with the private sector to provide incentives to promote access, affordability, and use of mobile phones.

- ii) Bridge the gender skills divide: Digital financial literacy is critical for beneficiaries of G2P payments. The digital gender divide is aggravated by the literacy gap. Since women are less likely to own a mobile phone, it further limits their learning of digital financial skills. The G20 countries can develop a common framework for public-private partnerships to enhance digital and financial literacy.

iii) Create cash withdrawal networks: Women depend the most on accessible cash-out facilities, including ATMs and agents, to convert digital money into cash. A study of DBT in India found female beneficiaries faced barriers in the last mile of banking services, which hindered them from accessing benefits.[36] The business correspondents programme in India for cash-out agents is a successful example of how introducing more women as agents can lead to far greater financial inclusion of female beneficiaries as they find women easier to approach and more trustworthy.[37] The G20 can foster efforts of governments and financial institutions to create cash-out networks to support women.

- iv) Gender-responsive grievance redressal systems: Beneficiary feedback and grievance redressal systems should address the needs of female beneficiaries and the challenges and concerns they face. The systems should be broadly publicised, easily accessible, and ensure complaints are handled in a timely manner. The G20 can lay down principles to address vulnerability to errors and ensure maximum inclusion.

Attribution: Sunaina Kumar, “Strengthening Digital Financial Inclusion in Government-to-Person Payments to Women: Lessons for Emerging Economies,” T20 Policy Brief, June 2023.

[1] ”Direct Benefit Transfer,” Government of India, last modified 2023 https://dbtbharat.gov.in/

[2] Government of India, “Direct Benefit Transfer.”

[3] Ugo Gentilini et al., Social Protection and Jobs Responses to COVID-19: A Real-Time Review of Country Measures (World Bank, 2021), https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/281531621024684216/pdf/Social-Protection-and-Jobs-Responses-to-COVID-19-A-Real-Time-Review-of-Country-Measures-May-14-2021.pdf

[4] Cristian Alonso, Tanuj Bhojwani et al., “Stacking up the Benefits: Lesson from India’s Digital Journey,” IMF, March 31, 2023, https://www.elibrary.imf.org/view/journals/001/2023/078/article-A001-en.xml

[5] Government of India, “Direct Benefit Transfer.”

[6] Shamika Ravi, “Is India Ready to Jam,” The Brookings Institution, August 27, 2018, https://www.brookings.edu/research/is-india-ready-to-jam/

[7] Debosmita Sarkar and Sunaina Kumar, “Women-centric Approaches Under MUDRA Yojana: Setting G20 Priorities for the Indian Presidency,” Observer Research Foundation, October 25, 2022, https://www.orfonline.org/research/women-centric-approaches-under-mudra-yojana/

[8] Alonso et al., “Stacking up the Benefits”

[9] Asli Demirguc-Kunt et al., The Global Findex Database 2021, Financial Inclusion, Digital Payments, and Resilience in the Age of COVID-19 (Washington, DC: The World Bank, 2021), https://www.worldbank.org/en/publication/globalfindex

[10] Alanso et al, “Stacking up the Benefits”

[11] Gentilini et al., “Social Protection and Jobs Responses to COVID-19: A Real-Time Review of Country Measures,”

[12] Demirguc-Kunt et al., “The Global Findex Database 2021.”

[13] Demirguc-Kunt et al., “The Global Findex Database 2021.”

[14] Abhishek Jain et al., A review of the effectiveness of India’s direct benefit transfer (DBT) system during COVID-19: Lessons for India and the world (Lucknow: MicroSave Consulting, 2020) https://www.microsave.net/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/Covid-publication-Effectiveness-of-Indias-DBT-system-during-COVID-19-1.pdf

[15] “National Family Health Survey-5” , Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, last modified 2021 http://rchiips.org/nfhs/NFHS-5_FCTS/India.pdf

[16] Zimmerman et al, Digital Cash Transfers in the Time of Covid 19: Opportunities and Considerations for Women’s Inclusion and Empowerment (World Bank, 2020), https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/378931596643390083/pdf/Digital-Cash-Transfers-in-Times-of-COVID-19-Opportunities-and-Considerations-for-Womens-Inclusion-and-Empowerment.pdf

[17] Gelb et al, Beyond India’s Lockdown: PMGKY Benefits During the COVID-19 Crisis and the State of Digital Payments (Washington, DC: Centre for Global Development, 2022), https://www.cgdev.org/sites/default/files/beyond-indias-lockdown-pmgky-benefits-during-covid-19-crisis-and-state-digital-payments.pdf

[18] Demirguc-Kunt et al., “The Global Findex Database 2021.”

[19] Zimmerman et al, “Digital Cash Transfers in the Time of Covid 19.”

[20] “Assam Orunodoi Scheme,” Assam State Portal, last modified June 16, 2023, https://assam.gov.in/scheme-page/154

[21] Demirguc-Kunt et al., “The Global Findex Database 2021.”

[22] GPFI, Women’s World Banking and the World Bank, Advancing Women’s Digital Financial Inclusion (G20 Global Partnership for Financial Inclusion by the Better Than Cash Alliance, Women’s World Banking, World Bank Group, 2020), https://www.gpfi.org/sites/gpfi/files/sites/default/files/saudig20_women.pdf

[23] Shruti Jain, “Harnessing digital financial inclusion under the G20 Digital Economy Agenda 2023,” Observer Research Foundation, February 8, 2022, https://www.orfonline.org/expert-speak/g20-digital-economy-agenda-2023/

[24] OECD, Gender equality in the G20 – Additional analysis from the time dimension, (Tokyo: OECD, 2019) https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—dgreports/—cabinet/documents/publication/wcms_713376.pdf

[25] Reena Ninan, “How Cash Transfers Bring More Women Into the Workforce”, Foreign Policy, March 10, 2022, https://foreignpolicy.com/2022/03/10/how-cash-transfers-bring-more-women-into-the-workforce/

[26] “Bridging the digital divide with innovative finance and business models,” International Telecommunication Union, last modified November 19, 2021, https://www.itu.int/hub/2021/11/bridging-the-digital-divide-with-innovative-finance-and-business-models/

[27] ITU, UNESCO, Doubling Digital Opportunities Enhancing the Inclusion of Women & Girls In the Information Society, (Geneva: ITU, UNESCO, 2013), https://www.broadbandcommission.org/Documents/working-groups/bb-doubling-digital-2013.pdf

[28] “Brazil´s Auxilio Emergencial: How digitization supported the response to COVID-19,” The World Bank, last modified December 15, 2021, https://www.worldbank.org/en/events/2021/12/15/Brazils-Auxilio-Emergencial;

Sophie Theis et al., “Indonesia’s largest cash transfer program pivoted quickly in response to Covid-Can beneficiaries keep up?” Women’s World Banking, October 7, 2020, https://www.womensworldbanking.org/insights/indonesias-largest-cash-transfer-program-

pivoted-quickly-in-response-to-covid-19/

[29] Greta L Bull, et al, “Building back better means designing cash transfers for women’s empowerment,” The World Bank, August 10, 2020, https://blogs.worldbank.org/voices/building-back-better-means-designing-cash-transfers-womens-empowerment

[30] Gentilini et al., “Social Protection and Jobs Responses to COVID-19.”

[31] GPFI, Women’s World Banking, The World Bank Group, Advancing Women’s Digital Financial Inclusion (GPFI, Women’s World Banking, The World Bank Group, 2020), https://www.gpfi.org/sites/gpfi/files/sites/default/files/saudig20_women.pdf

[32] “Does the initiative to increase awareness of DBT cater to female beneficiaries?” MicroSave Consulting, last modified November 7, 2022, https://www.microsave.net/2022/11/07/does-the-initiative-to-increase-awareness-of-dbt-cater-to-female-beneficiaries/

[33] Zimmerman et al, “Digital Cash Transfers in the Time of Covid 19.”

[34] The World Bank Group, “Advancing Women’s Digital Financial Inclusion.”

[35] Dominica Lindsey, “Top 10 recommendations for reaching women with mobile,” GSMA, April 1, 2021, https://www.gsma.com/mobilefordevelopment/blog/top-10-recommendations-for-reaching-women-with-mobile/

[36] “Exclusion from Social Protection Cash Transfers: Citizen Challenges and Administerial Perspectives,” Dvara Research, last modified December 2021, https://www.dvara.com/research/social-protection-initiative/exclusion-from-social-protection-cash-transfers-citizen-challenges-and-administerial-perspectives/

[37] Alreena Renita Pinto and Amit Arora, “Digital Doorstep Banking: Female Banking Agents Lead Digital Financial Inclusion Through The Pandemic and Beyond,” Asian Development Bank Institute, August 2021, https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/736831/adbi-wp1285.pdf