Task Force 6: Accelerating SDGs—Exploring New Pathways to the 2030 Agenda

Abstract

Gender gaps and female employment barriers have long been a prominent concern for countries around the world. One effective strategy to address these challenges involves narrowing the gaps and eliminating the barriers that prevent women from acquiring the skills they need to effectively participate in the labour market. The Indonesian government respond to the need for adequate training access for all, including women, through the ‘Kartu Prakerja’ programme, which provides thousands of relevant training modules to the labour force. Kartu Prakerja promotes end-to-end digital implementation, a customer-centric approach, and on-demand videos that facilitate easy access to training, and creates personalised learning journeys. These unique features provide women with the flexibility to take the training at their preferred time and place. Similar programmes can be replicated in other G20 countries.

1. The Challenge

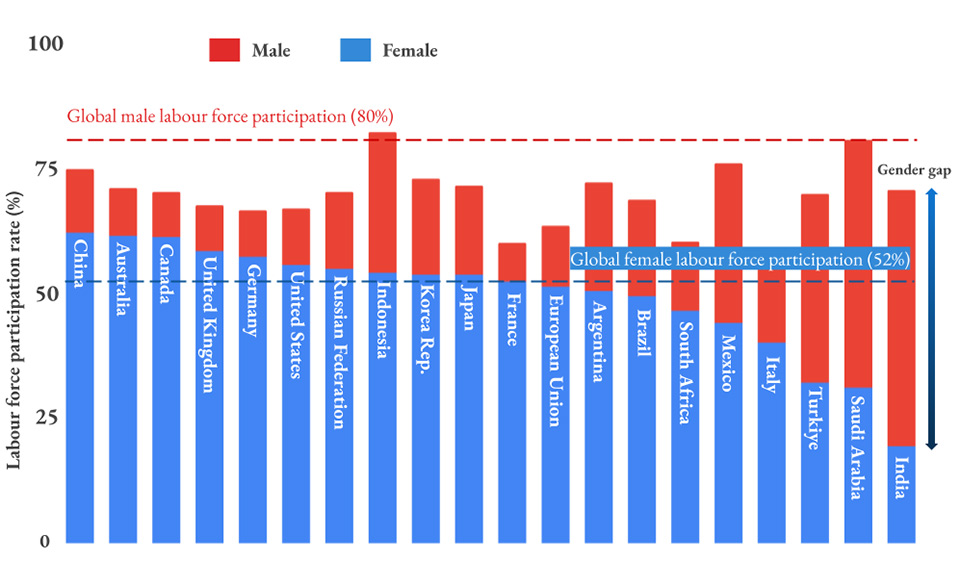

Low female labour force participation (FLFP) has been a concern in many countries. In Indonesia, FLFP is only 53.7 percent, which is 27.9 percent lower than male labour force participation (see Figure 1). Global data (up to 2019) shows that FLFP only touches 52.4 percent, compared to 80 percent for male labour force participation.[1] This stands true for several G20 countries as well. G20 developing economies, such as India, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, Italy, Mexico, South Africa, and Brazil, still have FLFP rates below 50 percent, as illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Labour Force Participation Rate in G20 Countries in 2021 (by gender)

Source: World Bank.[2]

The COVID-19 pandemic affected women disproportionately. In various Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries, on average, women spent 35 minutes more—twice as much as men—caring for children before the pandemic.[4] The situation has worsened since the pandemic. As primary caregivers, women were the family’s foundation in caring for children and family members during the pandemic. These additional family care responsibilities limited their participation in the labour market, forcing many to quit. Now, after withdrawing from the labour market, women will find it more difficult to re-enter, and may consequently remain outside the labour force.[5]

More than two years into the COVID-19 pandemic, most schools have reopened, yet the significant impact on learning loss persists. These effects are even more notable among marginalised and vulnerable groups of women. Around 54 percent of 130 million girls without formal education worldwide reside in crisis-affected countries.[6] Furthermore, a study of 193 countries found that women were up to 1.21 times more likely to drop out of school than men.[7] The pandemic also placed women at a greater risk of gender-based violence, mental health disorders, and food and economic insecurity. Therefore, non-formal education and social assistance are urgently needed.

There are several strategies to address the challenges of female employment, including providing training to prepare them for entry into the labour market. Skill development programmes have proven to positively impact the FLFP rate.[8] In the context of Indonesia, the government needs to invest in the labour force to resolve labour market challenges and build a better employment market with middle-income jobs.[9] Access to formal education can help strengthen the future workforce, while skilling, reskilling, and upskilling can keep the current workforce productive and adaptable to new high-skilled employment.

2. The G20’s Role

The G20’s role in amplifying women’s empowerment has been evident since 2014, marked by the Brisbane Target aiming to reduce the gender gap in labour force participation by 25 percent by 2025 in each G20 country, relative to its value in 2012. The commitment of G20 member countries to accelerate the achievement of this goal is reflected in their policies. Several G20 countries, such as France, Mexico, Australia, Canada, Japan, Singapore, Turkey, and the US, offer facilities or compensation for childcare services for working mothers or parents with toddlers. Others, such as South Korea, Saudi Arabia, Canada, and Italy, allocate subsidies for employers who hire women. In countries like Brazil, France, the UK, Canada, Germany, and Spain, support is also provided for specific groups of women, such as those in economically vulnerable situations, migrant women, and women experiencing long-term unemployment.[10]

Despite various initiatives to empower women within the working age population, the journey to achieving the Brisbane Target remains challenging. The challenge is exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, which has had a more severe impact on women. However, several G20 members have made progress in narrowing the gender gap in participation (see Appendix 1). As of 2021, several countries including Germany, the UK, Belgium, Luxembourg, Malta, the Netherlands, Portugal, the Slovak Republic, Slovenia and Sweden have notably met the target of reducing the gender participation gap by 25 percent compared to 2012. Apart from these, almost half of G20 member countries have seen improvements in reducing the gap. However, according to Appendix 1, several countries have not witnessed any progress (Canada, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Latvia, and Poland) and many others have experienced negative growth in gender gap participation (Bulgaria, Russia, Hungary, Lithuania, and Romania). These trends indicate that significant efforts need to be undertaken to ensure the Brisbane Target is achieved by 2025.

To intensify their efforts, in 2021, the G20 member states have formulated a G20 Roadmap Towards and Beyond the Brisbane Target to enhance the quality of women’s employment.[11] This roadmap includes six objectives: enhancing the quantity and quality of women’s employment; guaranteeing equal opportunities and achieving better outcomes in the labour market; promoting a more balanced representation of women and men across sectors and occupations; addressing the gender pay gap; encouraging a more equitable distribution of paid and unpaid work between women and men; and confronting discrimination and gender stereotypes in the workplace.

The momentum continued into 2022, when G20 members approved the Bali G20 Leaders Declaration, which, among other aspects, addressed initiatives to empower women.[12]

Empowering women: The role of Kartu Prakerja

As one of the G20’s emerging economies, Indonesia has provided empirical evidence on how large-scale skill development and social assistance initiatives can eliminate women’s barrier to develop their skills, thus improving their situation during the pandemic. A novel initiative, the Kartu Prakerja Programme, also known as Prakerja, offers training vouchers to beneficiaries, allowing them to select from thousands of available training topics within the Prakerja ecosystem. Upon completing the training and obtaining a skills certificate, they also receive post-training incentives. The programme is open to all Indonesian workers, particularly those impacted by COVID-19, men or women aged between 18 and 64 years. Prakerja removes the selection bias that often plagues government programmes by applying a rigorous randomisation method to all applicants.

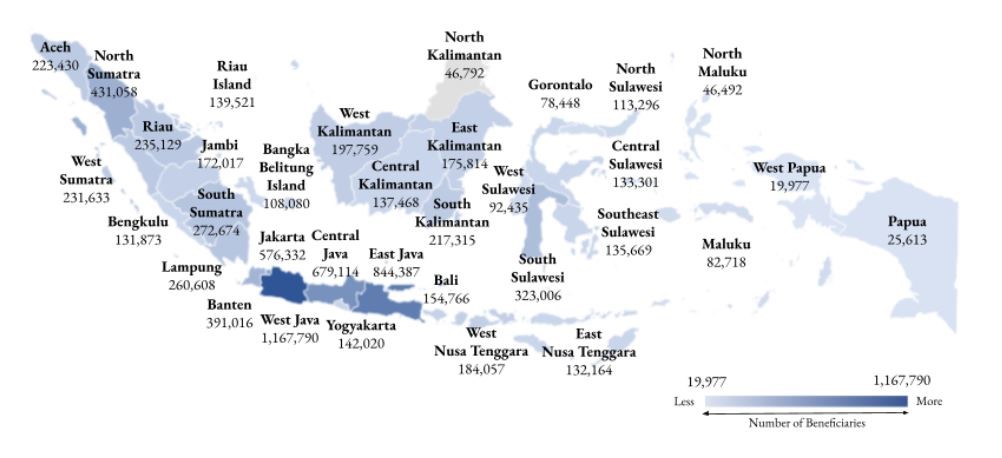

Since the beginning of 2020, Prakerja has increased Indonesian workforces’ exposure to adult learning. Through an end-to-end digital approach and public-private partnership (seven assessor teams, 11 monitoring teams, 188 training institutions, six digital platforms, six payment partners and four job portals), Prakerja successfully reached 16.4 million beneficiaries in less than three years, including 8.3 million female beneficiaries from 514 districts and cities in Indonesia (see Figure 2). Prakerja’s female beneficiaries come from all groups of society and backgrounds—around 66 percent of these women were unemployed before participating in the programme, 87 percent had never attended any training, 12 percent were over 50 years old, and 65 percent lived in rural areas. Additionally, 47 percent hailed from extremely poor districts, and three percent were people with disabilities. Most female beneficiaries (around 83 percent) have lower educational attainment (senior high school or below).[13]

Figure 2: Female Beneficiaries Distribution Across Provinces in Indonesia

Source: Prakerja Management Office Administrative Data 2020-2022.[14]

Outcomes of the Kartu Prakerja programme

Evaluation survey by the Prakerja Management Office (PMO) indicate that Prakerja successfully benefits women in several aspects: skills development, labour market outcomes, well-being and financial inclusion. These surveys were sent to all beneficiaries, with responses from 7.2 million female beneficiaries. More than 91 percent female beneficiaries stated that Prakerja’s training increased their competence through skilling, reskilling, and upskilling. A substantial percentage of female beneficiaries stated that Prakerja’s training improved their cognitive (82 percent), interpersonal (81 percent), leadership (84 percent) and digital (82 percent) skills. As a result, around 22 percent of female beneficiaries, previously unemployed before participating in Prakerja, have now found work as employees (9 percent) or entrepreneurs (13 percent).

Not only does Prakerja offer skills development and improved employment opportunities, it also provides beneficiaries with post-training incentives as social assistance. About 87 percent of female beneficiaries use their post-training incentive to buy staple food, and 68 percent also use it as business capital to start businesses or finance their daily operation. Furthermore, another positive externality from Prakerja is financial inclusion. Since joining the programme, 30 percent of female beneficiaries who previously did not have a bank account or an e-wallet, now have one of the accounts.[15]

Evidence from impact evaluation research indicates that Prakerja improved women’s skills and labour market outcomes. Female beneficiaries have reported higher competencies (2.9 percent), productivity (3.3 percent), competitiveness (3.8 percent), entrepreneurial skills (40.9 percent), and increased income (33 percent) compared to female non-beneficiaries.[16] Higher training intensity at Prakerja (number of training taken and training duration in minutes) also positively impacted women’s employment, including the probability of having a business, working as an employee, getting formal work, income, working hours, and productivity.

Among other groups, unemployed women benefitted the most as they have the highest probability of achieving labour market outcomes. Moreover, completing the training with excellence (finishing the training and passing the standard for the post-training test score) imposed a more significant impact on female beneficiaries (see Appendix 2).[17]

3. Recommendations to the G20

Several key factors that underlie the success of Prakerja in scaling up women’s empowerment in Indonesia can be replicated in other G20 countries. These include:

Implementing an end-to-end digital programme

Prakerja implements an end-to-end digital programme that reduces the time and effort required to operate a programme. At Prakerja, all activities are digitally recorded, which enables implementers to gain valuable insights related to its operation, make data-driven decisions, and continuously improve the service quality by iteration. Moreover, this approach helps the programme reach millions of people in archipelagic Indonesia. Eligible participants, including women with training barriers (such as having family care responsibility, living in rural areas, having limited time to travel, etc), are able to register independently from anywhere on the programme’s website.

Empowering women through voice and choice

A women’s empowerment programme should emphasise ‘voice and choice’ principles. The ‘choice’ principle means the programme should provide women with various choices that allow beneficiaries to make decisions based on their needs, as demonstrated by Prakerja. Individuals can register on the Prakerja’s website, join the recurring batch, and choose tailor-made trainings best suited to their positions. During the pandemic, Prakerja provided online training (through on-demand video and synchronous webinar, or combinations of both) with a variety of schedule options to ensure time and place flexibility for those who needed to adjust their working hours and domestic activities. Additionally, the programme allowed women to attend male-biased trainings. For instance, women may now attend electricity installation, computer assembly, and smartphone repair training sessions that are generally chosen by men as their occupation. Similarly, men can participate in traditionally female-dominated training like make-up, tailoring, salon, and beauty services.

Moreover, the ‘voice’ principle means the programme should facilitates the women to voice their needs and suggestions. As this principle is implemented in Prakerja through a review and rating system, this programme can collect input from beneficiaries at every training. This programme design will help the PMO monitor and impose sanctions on training providers that do not comply with the regulations. Therefore, ratings and reviews act as indicators of the quality of each training session, signalling the PMO, and helping maintain the standards of training.

Establishing collaboration with multiple Stakeholders

Public–private partnerships are the key to building a well-functioning ecosystem, where all participants share responsibilities and risks. A successful example of this is the Prakerja programme, which has created a large-scale online training ecosystem. Such partnerships can foster a more inclusive approach for all groups, including women. The PMO plays a critical role in maintaining seamless operation and interoperability within the ecosystem by providing an application programming interface and acting as the principal, host and regulator. As the principal, the PMO designs the programme and integration system, provides the server as the host and sets operational rules as the regulator.

Fostering a user-centric programme approach

A programme should prioritise the needs of beneficiaries and user-centric value on its implementation, thereby enhancing the experience of beneficiaries through faster, more convenient, and personalised services. The PMO’s evaluation survey has proved Prakerja’s high-quality service. About 90 percent of female beneficiaries stated that Prakerja’s application process is easy or simple. Moreover, 95 percent of female beneficiaries who used Prakerja’s contact centre services said it is reliable.[18]

Facilitating female beneficiaries to establish networks

Supporting women through networks may help them gather relevant and accurate information to improve their employment and well-being. Prakerja’s ecosystem provides female beneficiaries with plenty of information channels and networks between class members and instructors. About 42 percent of women have access to online forums on websites or communication channels, such as WhatsApp, Telegram and LINE, through their training classes. Among those with access, 71 percent participated in the online forum by asking questions or engaging in discussions. Interestingly, 74 percent of female beneficiaries used the online forum to keep in contact with their training classmates, and 71 percent to stay connected with their training instructor.[19]

Designing appropriate incentives for women

Incentive plays a crucial role in enhancing enrolment in government programmes. Policymakers need to understand social and economic contexts, and make careful calculations to design effective incentives that motivate people. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the Indonesian government gave Prakerja an additional mandate to maintain people’s purchasing power, even though the programme’s primary purpose is to develop skills. Hence, the post-training incentives of Prakerja serve two essential roles: social assistance and opportunity cost coverage, which is delivered after the beneficiaries complete the training, receive their skill certificates, and submit their ratings and reviews. The post-training incentives is IDR600,000 (US$41) per month (disbursed within four months) with IDR1,000,000 (US$68) training vouchers. For women who need to support their families, the post-training incentive is beneficial as it can cover 63 percent of the female beneficiaries’ average monthly food expenses.[20] The post-training incentives can also, on average, cover 37 percent of women’s monthly wage. PMO calculations using the National Labour Force Survey data show that monthly wages on average amount to IDR1,608,942 (US$109) (see Appendix 3).[21]

Implementing government-to-person payment 3.0 for disbursing social assistance

Government-to-Person (G2P) Payment 3.0 enables the government to disburse cash transfers through various channels, such as bank accounts and e-wallets, allowing beneficiaries to choose the most suitable disbursement channel. During the pandemic, this G2P 3.0 system successfully made large-scale incentive disbursements with high accuracy, speed and transparency. It also circumvented the time and costs associated with a single-channel G2P, allowing beneficiaries to maximise their benefits. Prakerja has demonstrated that a multichannel G2P also can also accelerate financial inclusion and promote financial deepening as positive externalities. Lastly, effective and prompt payment through this mechanism have been shown to prevent poverty and foster economic resilience.[22]

Attribution: Bambang Brodjonegoro et al., “Scaling Up Women’s Empowerment During the Pandemic and Beyond: Lessons from Indonesia’s ‘Kartu Prakerja’ Programme,” T20 Policy Brief, June 2023.

Appendices

Appendix 1

Table 1: Progress of the G20 in Reducing the Gender Participation Gap

| Country | Labour Participation Rate in 2012 (%) | Labour Participation Rate in 2021 (%) | Progress on Gap (%) |

||||

| Male | Female | Gap | Male | Female | Gap | ||

| Argentina | 74 | 48 | – 26 | 72 | 50 | – 22 | 15 |

| Australia | 72 | 59 | – 13 | 71 | 61 | – 10 | 23 |

| Austria | 67 | 55 | – 12 | 66 | 56 | – 10 | 17 |

| Belgium | 60 | 47 | – 13 | 59 | 50 | – 9 | 31 |

| Brazil | 74 | 51 | – 23 | 68 | 49 | – 19 | 17 |

| Bulgaria | 59 | 48 | – 11 | 63 | 49 | – 14 | – 27 |

| Canada | 71 | 62 | – 9 | 70 | 61 | – 9 | 0 |

| China | 78 | 64 | – 14 | 74 | 62 | – 12 | 14 |

| Croatia | 59 | 45 | – 14 | 59 | 46 | – 13 | 7 |

| Cyprus | 70 | 57 | – 13 | 69 | 57 | – 12 | 8 |

| Czechia | 68 | 50 | – 18 | 68 | 52 | – 16 | 11 |

| Denmark | 67 | 58 | – 9 | 67 | 58 | – 9 | 0 |

| Estonia | 68 | 55 | – 13 | 70 | 57 | – 13 | 0 |

| Finland | 64 | 56 | – 8 | 64 | 56 | – 8 | 0 |

| France | 62 | 52 | – 10 | 60 | 52 | – 8 | 20 |

| Germany | 66 | 54 | – 12 | 66 | 57 | – 9 | 25 |

| Greece | 61 | 44 | – 17 | 58 | 43 | – 15 | 12 |

| Hungary | 59 | 45 | – 14 | 67 | 52 | – 15 | – 7 |

| India | 78 | 23 | – 55 | 70 | 19 | – 51 | 7 |

| Indonesia | 83 | 51 | – 32 | 82 | 54 | – 28 | 13 |

| Ireland | 69 | 55 | – 14 | 69 | 57 | – 12 | 14 |

| Italy | 59 | 40 | – 19 | 58 | 40 | – 18 | 5 |

| Japan | 71 | 48 | – 23 | 71 | 53 | – 18 | 22 |

| South Korea | 73 | 50 | – 23 | 72 | 53 | – 19 | 17 |

| Latvia | 66 | 54 | – 12 | 67 | 55 | – 12 | 0 |

| Lithuania | 63 | 53 | – 10 | 68 | 57 | – 11 | – 10 |

| Luxembourg | 66 | 52 | – 14 | 66 | 58 | – 8 | 43 |

| Malta | 66 | 39 | – 27 | 71 | 53 | – 18 | 33 |

| Mexico | 78 | 44 | – 34 | 75 | 44 | – 31 | 9 |

| Netherlands | 71 | 59 | – 12 | 71 | 62 | – 9 | 25 |

| Poland | 64 | 48 | – 16 | 65 | 49 | – 16 | 0 |

| Portugal | 66 | 55 | – 11 | 62 | 54 | – 8 | 27 |

| Romania | 64 | 46 | – 18 | 62 | 43 | – 19 | – 6 |

| Russian Federation | 71 | 56 | – 15 | 70 | 54 | – 16 | – 7 |

| Saudi Arabia | 78 | 20 | – 58 | 80 | 31 | – 49 | 16 |

| Slovak Republic | 68 | 51 | – 17 | 66 | 55 | – 11 | 35 |

| Slovenia | 63 | 52 | – 11 | 62 | 54 | – 8 | 27 |

| South Africa | 60 | 45 | – 15 | 60 | 46 | – 14 | 7 |

| Spain | 66 | 53 | – 13 | 62 | 53 | – 9 | 31 |

| Sweden | 67 | 60 | – 7 | 68 | 62 | – 6 | 14 |

| Türkiye | 71 | 29 | – 42 | 69 | 32 | – 37 | 12 |

| UK | 69 | 56 | – 13 | 67 | 58 | – 9 | 31 |

| US | 69 | 57 | – 12 | 66 | 55 | – 11 | 8 |

Sources: Authors’ calculations using World Bank data in 2012 and 2021.[23]

Notes: The gap indicates the percentage point difference between male and female labour participation rate in each year. Whereas “Progress on Gap” is the percentage of gap reduction between 2012 and 2021.

Appendix 2

Table 2.1: Estimates of the Numbers of Completed Training Effects on Labour Market Outcomes

| Dependent Variables: Labour Market Outcomes | Independent Variable: Numbers of Completed Trainings | |||

| I: All sample | II: Unemployed | III: Entrepreneur | IV: Employee | |

| Having a business | 0.152*** | 0.0547*** | – | – 0.284*** |

| Working as an employee | 0.243*** | 0.126*** | – 0.00612 | – |

| Income | 170,746*** | 67,485*** | 205,992*** | 140,674** |

| Working hours | 4.312*** | 1.517*** | 2.668*** | 3.165*** |

| Productivity | 2,584*** | 1,728*** | – 10,833*** | – 14,326** |

Sources: Authors’ calculations using 2021 and 2022 PMO’s administrative and survey data.

Notes: The signs ***, **, * indicate 0.01, 0.05 and 0.1 significance levels. Having a business, working as an employee, and becoming a formal employee are expressed in probability. Income is in IDR, working hours in hours, and productivity is in IDR/hour.

Table 2.2: Estimates of the Training Completed with Excellence Effects on Labour Market Outcomes

| Dependent Variables: Labour Market Outcomes | Independent Variable: Numbers of Training Completed with Excellence | |||

| I: All sample | II: Unemployed | III: Entrepreneur | IV: Employee | |

| Having a business | 0.268*** | 0.0956*** | – | – 0.508*** |

| Working as an employee | 0.444*** | 0.233*** | -0.0094 | – |

| Income | 300,836*** | 116,461*** | 408,747*** | 322,550** |

| Working hours | 7.598*** | 2.619*** | 5.294*** | 7.258*** |

| Productivity | 4,553*** | 2,982*** | – 21,495*** | – 32,847** |

Sources: Authors’ calculations using 2021 and 2022 PMO’s administrative survey data.

Notes: The signs ***, **, * indicate 0.01, 0.05 and 0.1 significance levels. Having a business, working as an employee, and becoming a formal employee are expressed in probability. Income is in IDR, working hours in hours, and productivity is in IDR/hour.

Table 2.3: Estimates of the of Training Duration (in Minutes) Effects on Labour Market Outcomes

| Dependent Variables: Labour Market Outcomes | Independent Variable: Training duration in minutes | |||

| I: All sample | II: Unemployed | III: Entrepreneur | IV: Employee | |

| Having a business | 0.0281*** | 0.0102*** | – | – 0.0510*** |

| Working as an employee | 0.0457*** | 0.0243*** | – 0.0010 | – |

| Income | 31,796*** | 12,716*** | 37,132*** | 25,548** |

| Working hours | 0.803*** | 0.286*** | 0.481*** | 0.575*** |

| Productivity | 481.3*** | 325.5*** | -1,953*** | – 2,602** |

Sources: Authors’ calculations using 2021 and 2022 PMO’s administrative and survey data.

Notes: The signs ***, **, * indicate 0.01, 0.05 and 0.1 significance levels. Having a business, working as an employee, and becoming a formal employee are expressed in probability. Income is in IDR, working hours in hours, and productivity is in IDR/hour.

Table 2.4. Estimates of the Training Intensity Effects on Probability of Becoming a Formal Employee

| Independent Variables | Dependent Variable: Becoming a formal employee | ||

| I: All sample | II: Unemployed | III: Informal Employee | |

| Numbers of Completed Trainings | 0.366*** | 0.364*** | 0.307** |

| Numbers of Training Completed with Excellence | 0.679*** | 0.656*** | 0.597** |

| Training duration in minutes | 0.0698*** | 0.0708*** | 0.0539** |

Sources: Authors’ calculations using 2021 and 2022 PMO’s administrative and survey data.

Notes: The signs ***, **, * indicate 0.01, 0.05 and 0.1 significance levels. Having a business, working as an employee, and becoming a formal employee are expressed in probability. Income is in IDR, working hours in hours, and productivity is in IDR/hour.

Appendix 3

Table 3: Monthly Wage and Hourly Earnings for Indonesian Female Workforce in 2022

| Work Status | #People | Education

(years) |

Monthly wage

(IDR) |

Work hours | Earnings per hour (IDR) |

| Total Workforce | 55,157,803 | 9.12 | 1,608,942 | 32.15 | 10,056 |

| Self-employed | 11,007,705 | 7.86 | 1,086,491 | 32.90 | 6,791 |

| Self-employed + temporary worker | 6,520,299 | 7.56 | 1,268,105 | 37.94 | 7,926 |

| Self-employed + permanent worker | 818,521 | 10.23 | 3,054,486 | 37.84 | 19,091 |

| Employee | 17,928,450 | 12.78 | 2,206,993 | 34.31 | 13,794 |

| Freelance agriculture | 1,834,384 | 6.14 | 719,436 | 28.68 | 4,496 |

| Freelance non-agriculture | 1,062,926 | 7.35 | 806,076 | 29.51 | 5,038 |

| Work without pay | 12,614,924 | 7.50 | – | 26.90 | – |

| Unemployed | 3,370,594 | 10.41 | – | – | – |

Sources: Authors’ calculations using The National Labour Force Survey, February 2022 (Sakernas BPS).

Endnotes

[1] World Bank, Female Labour Force Participation, August 9, 2022.

[2] World Bank, Labor force participation rate (% of population), 2022.

[3] Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development and International Labour Organization, Women at Work in G20 Countries: Progress and Policy Action, OECD and ILO, 2019.

[4] Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Women at the Core of the Fight against COVID-19 Crisis, OECD, 2020.

[5] Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development and International Labour Organization, Women at Work in G20 Countries: Policy Action Since 2020, OECD and ILO, 2021.

[6] Department of Economic and Social Affairs, United Nations, The Progress on the Sustainable Development Goals: The Gender Snapshot 2022, UN, 2022.

[7] Rosemary Morgan, Denise N. Pimenta and Sabina Rashid, “Gender Equality and COVID-19: Act Now Before It Is Too Late,” Lancet 399, no. 10344 (2022): 2327–2329.

[8] Indrajit Bairagya, Tulika Bhattacharya, and Pragati Tiwari, “Does Vocational Training Promote Female Labour Force Participation? An Analysis for India,” Margin: The Journal of Applied Economic Research 15, no. 1 (2021).

[9] Denni Purbasari, Elan Satriawan, and Romora E. Sitorus, “Kartu Prakerja: A Breakthrough for Boosting Labour Market Productivity and Social Assistance Inclusiveness,” in Keeping Indonesia Safe from the COVID-19 Pandemic: Lessons Learnt from the National Economic Recovery Programme, edited by Sri Mulyani Indrawati, 291–317, Singapore: ISEAS Publishing, 2022.

[10] OECD and ILO, Women at Work in G20 Countries: Policy Action Since 2020.

[11] G20 Labour and Employment Ministerial Declaration, Fostering an Inclusive, Sustainable, and Resilient Recovery of Labour Markets and Societies, G20 Italy, 2021.

[12] G20 Bali Leaders’ Declaration, 2022, https://www.g20.org/content/dam/gtwenty/gtwenty_new/about_g20/previous-summit-documents/2022-bali/G20 Bali Leaders%27 Declaration, 15-16 November 2022.pdf

[13] PMO Kartu Prakerja, Administrative Data 2020–2022 (17 April 2020 – 10 December 2022), 2022.

[14] PMO Kartu Prakerja, Administrative Data 2020–2022.

[15] PMO Kartu Prakerja, Evaluation Surveys 2020–2022 (5 August 2020 – 10 December 2022), 2022.

[16] “Impact Evaluation of Kartu Prakerja as a COVID-19 Recovery Program,” Presisi Indonesia, February 2022.

[17] Bambang Brodjonegoro, Romora E. Sitorus, Amirah J. Dhia, Daniera N. Ariefti and Rizki F. Pangestu, Dampak Intensitas Pelatihan Pada Penerima Perempuan: Studi Program Skala Besar Indonesia Di Masa Pandemi COVID-19 (Working Paper), 2023.

[18] PMO Kartu Prakerja, Evaluation Surveys 2020–2022.

[19] PMO Kartu Prakerja, Evaluation Surveys 2020–2022.

[20] PMO Kartu Prakerja, Evaluation Surveys 2020–2022.

[21] Statistics Indonesia, The National Labour Force Survey, February 2022.

[22] Meikha Azzani, Martha Hindriyani, Daniera Nanda, and Cahyo Prihadi, “Driving Inclusion and Resilience through Multi-channel Government-to-Person Payment: Lessons Learned from Indonesia’s Kartu Prakerja,” T20 Policy Brief (2022).

[23] World Bank, Labor force participation rate (% of population).