Task Force 5: Purpose and Performance: Reassessing the Global Financial Order

Global climate goals need continued attention in good times and in bad. However, the effects of recent global shocks have delayed progress on the net-zero transition, climate change adaptation and wider sustainability goals. Delay will increase the economic expense of transition and environmental damages. The global community can and must embed shock-proofing and shock-responsive approaches into fiscal policies and the evolving global financial architecture so that shocks no longer inhibit progress—this is referred to as a resilient net-zero transition. The G20, through its fiscal policies, financial regulation, and the Bretton Woods institutions, has a crucial role to play in shaping the architecture for a resilient net-zero transition. This Policy Brief recommends the creation of a dedicated financing facility for emerging and developing economies to help maintain progress on climate goals during crises; and that the G20 aligns the global financial system, including fiscal and development finance, with climate-resilient development.

1. The Challenge

Since the Paris Agreement (2015), the world has faced several shocks including COVID-19, and the Ukraine crisis and concomitant food and energy crises, rapid inflation with monetary tightening, and many climate disasters. These have delayed and constrained progress on the Paris objectives and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), hindering sustainable investments and increasing debt vulnerabilities, especially in emerging and developing economies (EMDEs). The SDG financing gap grew by US$1 trillion and private investment dropped.[1] Furthermore, the Ukraine crisis prompted increased fossil fuel investment.[2]

Globally, the net-zero transition and adaptation investment should not be delayed further. Inaction raises costs and harms.[3] While global shocks are not new, they become more likely due to climate change, biodiversity loss, and economic interconnectedness. The low-carbon transition itself is vital for resilience; reducing fossil fuel-dependence enhances immediate energy resilience and reduces long-term climate effects through lowering greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. This must pair with widespread investment to strengthen climate resilience, including natural capital. Postponing investment toward the Paris goals leads to a costlier transition, thereby harming the environment, economy, and people.[4]

Today, not all fiscal policies of countries are aligned with the Paris Agreement. This is undermining progress on climate action and resulting in missed opportunities, particularly in response to crises. Gaps in countries’ wider policy and in the financial and development architectures mean regression during crises. This Policy Brief argues that a proactive approach is required to closing the gaps and ensuring that the evolving green financial architecture responds to shocks.

Fiscal policy, sustainability, debt, and resilience

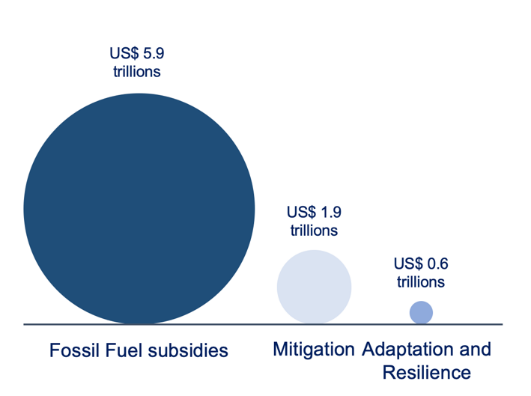

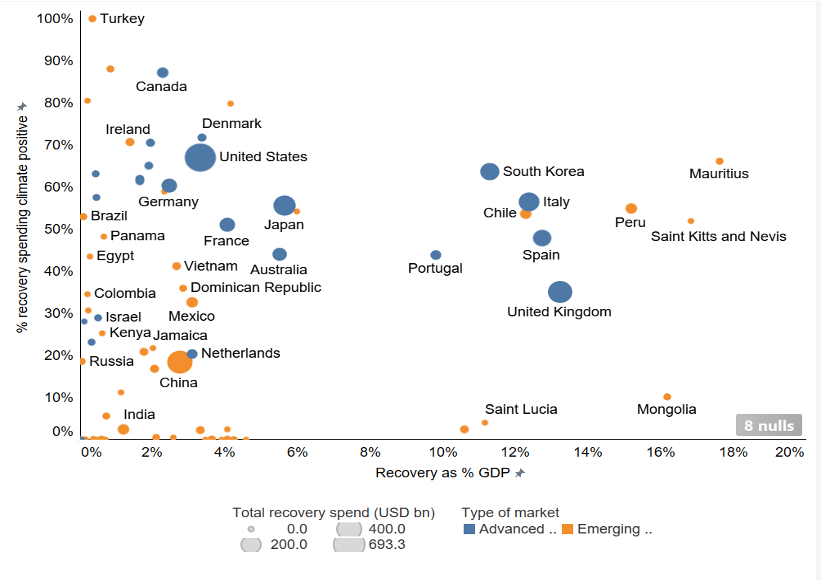

Fiscal policy affects sustainable development, both through the sectors it supports and its influence on short- and long-term resilience. In the short-term, during crises, fiscal policy can play an important role in mitigating effects through spending, taxation, and managing borrowing. Over time, it shapes investment and industrial patterns. Despite some progress, fiscal policy design in most countries does not fully account for climate risks. This leads to higher long-term costs and underinvestment in mitigation and climate change adaptation.[5] Failing to deal with externalities results in regressive policies, benefiting the wealthiest and harming the poorest. Amid crises, short-term pressures worsen the situation. Figure 1 compares global investment in climate goals during Covid-19 and fossil fuel subsidies.

Figure 1: ‘Climate-Positive’ Covid-19 Expenditures and Total Fossil Fuel Subsidies for 90 countries (2020–2021)

Source: Fiscal Affairs Department, IMF and Sadler et al. (forthcoming)[6].

Note: Fossil fuel subsidies include both explicit and implicit subsidies.

First, constrained fiscal space during and after crises hampers investment in sustainability and resilience. The compound effects of climate, pandemic, war, and high inflation have made the space for fiscal policy more uncertain and constrained. Government debt soared globally in 2020 as a result of Covid-19 and has remained high in many EMDEs.[7] Elevated debt and deficits impede long-term resilience by destabilising the economy and crowding-out sustainable investments. The finance gap has widened between advanced economies and developing countries, particularly in external sovereign debt. Advanced economies benefited from low interest rates and central bank debt purchases, while low-income countries (LICs) were unable to benefit to the same extent.[8] Rising central bank rates exacerbate debt vulnerabilities and affect net food and energy importers among EMDEs. These factors constrain fiscal space for climate resilience and net-zero investment—higher costs of finance in 2022 coincided with a drop in EMDE clean energy investment.[9]

Second, short-term crisis response policies often neglect environmental externalities, leading to harmful consequences. For example, poorly designed subsidies, meant to protect the poorest households and businesses, have resulted in unintended consequences—these are discussed in turn in the following paragraphs.

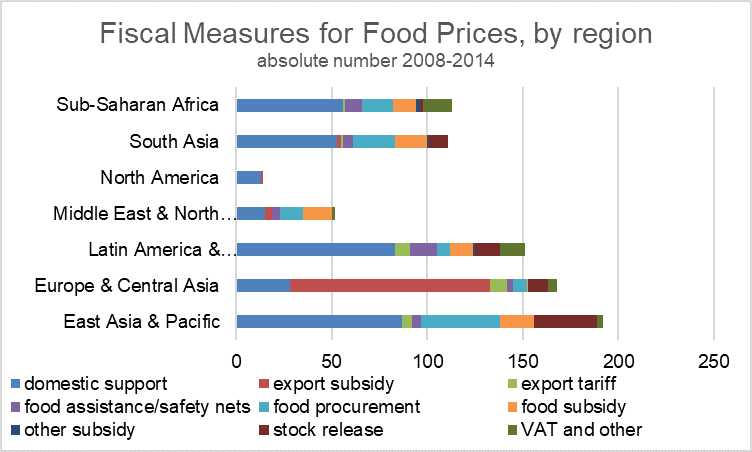

- Food. During the 2008 food price crisis, over 80 countries reduced food taxes or increased subsidies (see Figure 2). A similar pattern emerged in response to the Ukraine crisis. The environmental effects on agriculture and food, such as biodiversity loss, water insecurity, pollution, and associated economic and health effects, are not priced in the market.[10] Indeed, only 5 percent of government agricultural subsidies target conservation objectives,[11] and G20 economies’ subsidies distort the markets for LICs. This trade-off between short-term affordability and long-term sustainability hampers the green transition.

Figure 2: No. of Fiscal Measures Introduced (2008-2014) to Tackle Food Price Increases, by Type and Region

Source: Policy Monitor Dataset. Food Price Crisis Observatory, World Bank[12].

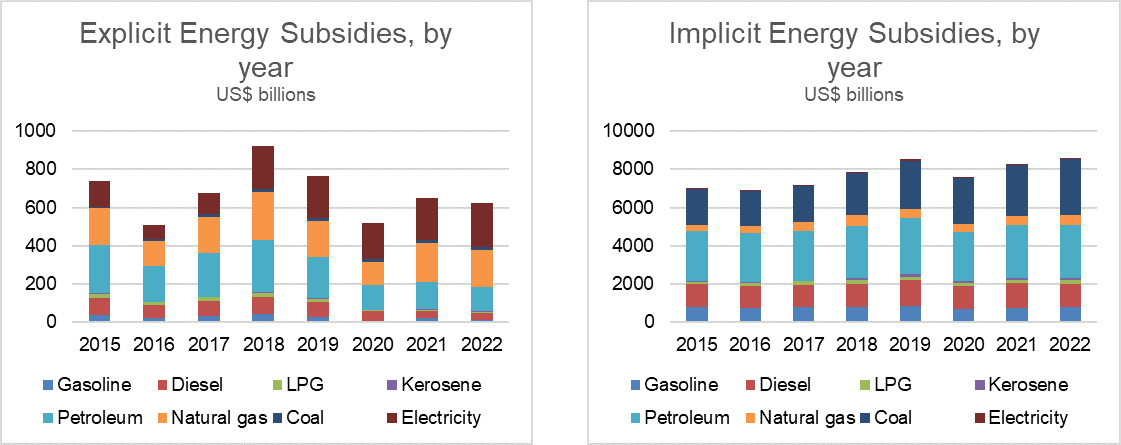

- Fuel. Despite G20 leaders’ pledge to phase out inefficient fossil fuel subsidies in 2009, both implicit and explicit subsidies have remained stagnant, with implicit subsidies surpassing explicit ones (see Figure 3). Subsidies for US crude oil producers and tax breaks have boosted profitability for new oil investments.[13],[14] However they come at a high cost, including fiscal expenses, inefficient resource allocation, pollution, and impeding investment in clean energy. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) estimates that reforming consumption subsidies could reduce emissions by up to 35 percent in some countries and save governments US$ 3 trillion by 2030.[15]

Figure 3: Total US$ Energy Subsidies (Explicit and Implicit) Adopted by Countries (2015–2022)

Source: Energy Subsidy Template. Fiscal Affairs Department, IMF[16]

The picture is particularly stark in energy and agriculture. Investments in food production and infrastructure are crucial for net-zero transition and resilience. However, when not aligned with sustainability and climate goals, they bring harm in the medium-term. Figure 4 shows minimal spending on energy and agriculture, with a higher share of ‘green’ investments in energy (88 percent) compared with agriculture (2.6 percent). Adaptation lags behind, with energy investments focused on mitigation. This suggests a high share of potentially detrimental measures to resilience, while spending on positive measures falls short of projected adaptation needs. Both G20 and the Vulnerable 20 (V20) countries face this problem (Figure 5), with varying alignment; G20 countries like Canada and the US show higher alignment, while India, China, and Russia show lower alignment.

Figure 4: Proportion of Covid-19 Spending for Climate-Positive and Non-Positive Measures

(Left) Total spending (US$, billions); (Right) Spending in energy and agriculture and fisheries. A&R = Adaptation and Resilience.

Source: Authors’ own

Figure 5. Recovery Spending (% of GDP) Vs. Recovery Spending Positive for Either Climate Change Mitigation or Adaptation and Resilience

Size of circles indicates total recovery spending (US$, billions). Coloured by type of market. Source: Sadler et al. (forthcoming)[20]

The role of private financial markets

Private sustainable finance markets continued to grow during recent crises[21] but total investment in fossil fuel technologies also increased in 2022 due to the war in Ukraine.[22] Sustainability-linked debt issuance has risen steadily in both advanced economies and EMDEs (Figure 6).[23] Although it is too early to attribute this momentum to specific climate or financial policies, the acceleration since 2015 indicates the influence of generally stronger policies. The momentum in finance is reflected in increased clean energy investment in advanced economies. However, investment in fossil fuels also rose during the Ukraine crisis, particularly in North America and the Middle East,[24] hindering progress.

Figure 6: Sustainability-Linked Debt Issuances in EMDEs

Source: Data from IMF 2022b Chapter 2[25]

2. The G20’s Role

A key part of shock-proofing climate goals is to swiftly align policy and finance with sustainability and accelerate financial mobilisation. Additionally, it is crucial to establish policies and mechanisms that shield global investment in net-zero and climate resilience, especially for EMDEs, such that shocks—natural or manmade—no longer set back progress against the Paris objectives and the SDGs. We refer to this new approach as the Resilient Net-Zero Transition.

G20 nations, through their fiscal and monetary policies, financial regulation and shareholding in IFIs, have a significant role to play in ensuring that the global financial architecture drives a stable and resilient net-zero transition in both good times and bad. Achieving a resilient net-zero transition requires coordinated policy across countries and new global mechanisms to support green recovery. Shaping the global financial architecture has been a raison d’etre of the G20 since its establishment in 1999.

The 2022 Leaders’ Declaration highlights synergies between food and energy security, climate mitigation and adaptation, and biodiversity conservation through efforts such as promoting SDG7, adopting a Post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework, endorsing the G20 Sustainable Finance Roadmap priorities, and calling for the phase-out of ‘inefficient’ fossil fuel subsidies. It also emphasises “the urgent need to strengthen policies and mobilise financing, from all sources in a predictable, adequate and timely manner” in support of climate action. The following points outline proposals for a set of principles and actions toward a resilient net-zero transition that link the Climate Goals to the core crisis response raison d’etre of the G20 and present a cohesive framework to practically advance past G20 commitments.

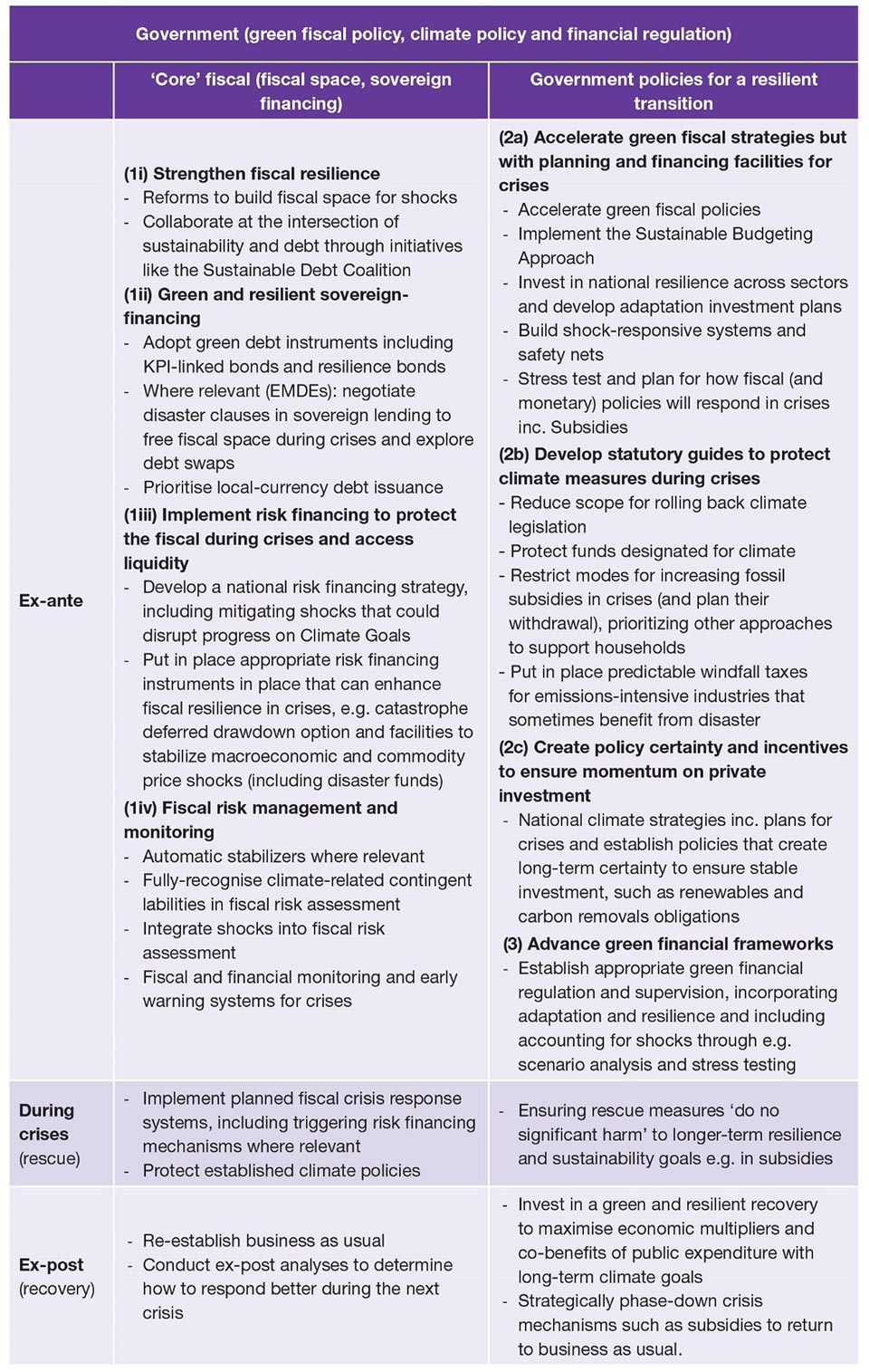

The set of principles and actions include both shock-proofing policies and establishing shock-responsive facilities and mechanisms, which draw from existing climate policies and established shock-proofing mechanisms.[28] These are summarised in Table 1. To meet the Paris goals and SDGs, the imperative is to proactively manage crisis risks within the strategies and the global financial architecture. The focus is on innovative measures beyond well-known policies like carbon taxes and scaled-up blended finance for adaptation. These include new net-zero crisis protection facilities, disaster-contingent clauses, debt-for-resilience and nature swaps, and other advancements that support the resilient transition.

Table 1a: Principles (in bold) and Actions for a Resilient Net-Zero Transition —Domestic Policies*

*The right-hand column lists policies that will support the resilient transition of the whole economy, and the left-hand column contains policies that concern the resilience of the government itself (including government spending).

Table 1b: Principles (in bold) and Actions for a Resilient Net-Zero Transition —International Policies

Green fiscal policy and the resilient transition

- Advance fiscal space, risk management, and risk financing to strengthen fiscal resilience to crises. Fiscal reforms and pre-arranged risk financing mechanisms help safeguarding the transition by enhancing fiscal resilience to crises sustaining public investment. Where appropriate, EMDE governments could explore green debt measures, including swaps and issuance of debtor-defined key performance indicator (KPI)-linked bonds to create fiscal space (and mobilise investment) and work with creditors to explore no-cost climate contingency (hurricane) clauses in sovereign lending. Developing markets for local currency denominated green debt should be prioritised to reduce the exposure of the national balance sheet to debt distress during shocks.

- Promote green fiscal strategies and ensure policy certainty for sustained private investment. Fiscal policies drive the resilient transition with significant fiscal multipliers, particularly for EMDEs.[29],[30] Environmental taxes discourage fossil fuel use, raise revenue, and foster innovation in cleaner, more efficient energy sources.[31] Policy objectives already encompass security (resilience), affordability, and clean energy and previous trade-offs fade as renewables become affordable and clean.[32] However, a resilient net-zero transition requires both accelerated green fiscal policies pre-crises and proactive plans, finance, and mechanisms to safeguard Paris goals during crises. Long-term policies like carbon taxes and carbon removal obligations ensure investment stability during crises, alongside statutory guidelines for legal enforcement. G20 countries must stress-test climate strategies for shocks, incentivise clean energy investment during crises (e.g. windfall taxes), and plan for efficient subsidy use and removal to minimise harm and provide market clarity.

Building a private financial architecture for a resilient transition

- Strengthen green financial frameworks, and incorporate resilience and adaptation. A robust green financial architecture is essential to ensure stable green financial flows during crises. More harmonised approaches across the G20 would prevent leakage and strengthen financial resilience against global shocks. Some G20 countries (Argentina, Mexico, South Africa, Indonesia, Turkey, Saudi Arabia, China and India) are yet to adopt mandatory Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures (TCFD)-aligned reporting. Gaps also exist in green prudential policies, taxonomies, green bond frameworks, and sustainability disclosures. Finance for adaptation lags behind. While net-zero approaches and coalitions exist, urgent attention is required to develop metrics and financial frameworks aligning finance with adaptation and resilience.[33]

The role of International Financial Institutions (IFIs)

- Scale-up global financial protection facilities. IFIs play a critical role in crises, including building fiscal space, enhancing resilience, and providing urgent liquidity. The G20 and IFIs should explore advantageously using existing global crisis finance like the IDA Crisis Response Window, IMF facilities, and G7 and V20 Global Shield to maintain climate and sustainability goals during crises. IFIs, including the IMF Resilience and Sustainability Trust, can assist the resilient transition by offering technical assistance, policy-based lending, and domestic green fiscal policies.

- Given the noteworthy influence and support of IFIs to countries, we must urgently close gaps in the alignment of development finance with climate and sustainability goals. We should also explicitly put in place policies, plans, and facilities to support clients throughout cycles of crises in ways that enhance long-term sustainability and resilience. IFIs should advance current work on integrating risk financing into lending operations specifically to allow finance for ‘climate goals’ to be scaled-up in crises where required. Funding from the United Nations, sovereigns, and civil society organisations can similarly be strategically targeted to support a resilient transition.

- Expand access to infrastructure and financing for climate goals during crises, including green recovery. A new multilateral green recovery facility could be established to provide pre-arranged financing to bridge gaps in clean energy and resilience investment during crises. This would help overcome fiscal constraints that can often hinder the energy transition in EMDEs during crises, as well as encourage greater preparedness for crises in fiscal policies.[34] Unlike existing concessionary mechanisms such as the Green Climate Fund, a green recovery facility would provide pre-arranged finance based upon risk financing principles, and built upon pre-agreed resilient transition plans, enabling it to more rapidly and efficiently allocate finance in crises.

3. Recommendations to the G20

- Adopt the concept of a ‘resilient net-transition’ and commit to align fiscal policy with climate and sustainability goals throughout the business cycle.

- Commit to align the global financial system, including fiscal policy and development finance, with climate-resilient development, as outlined in the 2015 Paris Agreement.

- Advance the alignment of the global financial architecture with both greenhouse gas emissions reductions and climate-resilient development, including establishing a G20 Sustainable Finance Working Group on resilience.

- Establish a task force, perhaps co-led by the G20 with IFIs, to develop a set of principles for a resilient net-zero transition and a strategy for how these can be integrated within the global financial architecture, including scoping potential facilities for shock-responsive finance.

Attribution: Nicola Ranger et al., “Reforming the Global Financial Architecture to Drive a Resilient Net-Zero Transition,” T20 Policy Brief, July 2023.

This research was supported by the ClimateWorks Foundation, the Green Fiscal Policy Network (GFPN), the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), the Oxford Martin School Systemic Resilience Programme, and the Climate Compatible Growth Programme of the United Kingdom’s Foreign, Commonwealth, and Development Office (FCDO). The views expressed in this paper do not necessarily reflect the views or official policies of any donor. We sincerely thank Christopher Adam, Stefan Dercon, Olivier Mahul, Alex Sadler, Anupama Sen, Christian Wilson, and Xiaoyan Zhou for their helpful inputs and reviews.

Endnotes

[1] OECD, Global Outlook on Financing for Sustainable Development 2021: A New Way to Invest for People and Planet (Paris: OECD Publishing, 2021), https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/sites/e3c30a9a-en/index.html?itemId=/content/publication/e3c30a9a-en.

[2] International Energy Agency, IEA Energy Investment 2022 (Paris: OECD Publishing, 2022).

[3]Vera Songwe, Nicholas Stern and Amar Bhattacharya, “Finance for climate action: scaling up Investment for climate and development,” Report of the Independent High-Level Expert Group on Climate Finance (Addis Ababa: UN, 2022), https://hdl.handle.net/10855/49154 .

[4] Hoesung Lee, Katherine Calvin, Dipak Dasgupta et al., Summary for Policymakers, in Synthesis Report of the IPCC Sixth Assessment Report – AR6 (Geneva: Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change,2023), https://report.ipcc.ch/ar6syr/pdf/IPCC_AR6_SYR_SPM.pdf.

[5] Nicholas Stern and Joseph E. Stiglitz, “Climate change and growth.” Industrial and Corporate Change 32, no. 2 (2023): 277-303, https://doi.org/10.1093/icc/dtad008.

[6]Alexandra Sadler, Nicola Ranger, Samuel Fankhauser, Fulvia Fankhauser and Brian O’Callaghan, “Did the COVID-19 Response Advance Climate Change Adaptation and Resilience?”, forthcoming.

[7] International Monetary Fund, IMF Fiscal Monitor: Fiscal Policy from Pandemic to War (Washington DC.: IMF, April 2022), https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/FM/Issues/2022/04/12/fiscal-monitor-april-2022.

[8]David Laborde, Csilla Lakatos and W.J. Martin, Poverty impact of food price shocks and policies, World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 8724 (Washington D.C.: World Bank, 2019), https://documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/863311549375011898/poverty-impact-of-food-price-shocks-and-policies.

[9] International Energy Agency, IEA Energy Investment 2022 (Paris: OECD Publishing, 2022).

[10]Timothy D. Searchinger, Chris Malins, Patrice Dumas, David Baldock, Joe Glauber, Thomas Jayne, Jikun Huang, and Paswell Marenya, Revising public agricultural support to mitigate climate change, (Washington D.C.: International Food Policy Research Institute, 2020). https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/entities/publication/7eef73a7-c4f6-590b-8e31-3a4051d875a9.

[11]David Laborde, Csilla Lakatos, and W.J. Martin, “Poverty impact of food price shocks and policies,” World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 8724 (Washington D.C.: World Bank, 2019), https://elibrary.worldbank.org/doi/abs/10.1596/1813-9450-8724.

[12] World Bank (20). Policy monitor. Food price crisis observatory. Available at: http://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/poverty/food- price-crisis-observatory#5

[13] Ronald Steenblik, “Analysing oil-production subsidies,” Nature Energy, 2, no. 11 (2017): 838-839, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41560-017-0027-6.

[14] Peter Erickson, Adrian Down, Michael Lazarus and Doug Koplow, “Effect of subsidies to fossil fuel companies on United States crude oil production,” Nature Energy, 2 (2017): 891-898, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41560-017-0009-8.

[15] Jonas Kuehl, Andrea M. Bassi, Phillip Gass and Georg Pallaske, Cutting emissions through fossil fuel subsidy reform and taxation (Geneva: International Institute for Sustainable Development, 2021). https://www.iisd.org/publications/cutting-emissions-fossil-fuel-subsidies-taxation.

[16] Parry, Ian, Mr Simon Black, and Nate Vernon. Still not getting energy prices right: A global and country update of fossil fuel subsidies. International Monetary Fund, 2021. Data available at: http://www.imf.org/external/np/fad/subsidies/index.htm.

[17] Brian O’Callaghan, “Reviewing the COVID-19 ‘Green Recovery’ for Mitigation: Rhetoric or Reality?” forthcoming.

[18] Alexandra Sadler, Nicola Ranger, Samuel Fankhauser, Fulvia Marotta, and Brian O’Callaghan, “Did the COVID-19 Response Advance Climate Change Adaptation and Resilience?” forthcoming.

[19] Barbara Buchner, Baysa Naran, Pedro Fernandes, Rajashree Padmanabhi, Paul Rosane, Matthew Solomon, Sean Stout, Costanza Strinati, Rowena Tolentino, Githungo Wakaba, Yaxin Zhu, Chavi Meattle, and Sandra Guzmán, Climate Policy Initiative- Global Landscape of Climate Finance (San Francisco: Climate Policy Initiative, 2021), https://www.climatepolicyinitiative.org/publication/global-landscape-of-climate-finance-2021.

[20]Alexandra Sadler, Nicola Ranger, Samuel Fankhauser, Fulvia Fankhauser and Brian O’Callaghan, “Did the COVID-19 Response Advance Climate Change Adaptation and Resilience?”, forthcoming.

[21] International Monetary Fund, World Economic Outlook, October 2022: Countering the Cost-of-Living Crisis (Washington D.C.: IMF, 2022), https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/Issues/2022/10/11/world-economic-outlook-october-2022.

[22] International Energy Agency, World Energy Investment 2022.

[23] International Monetary Fund, Countering the Cost-of-Living Crisis.

[24] International Energy Agency, World Energy Investment 2022.

[25] International Monetary Fund, Global Financial Stability Report, October 2022: Navigating the High-Inflation Environment (Washington D.C.: IMF, 2022) https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/GFSR/Issues/2022/10/11/global-financial-stability-report-october-2022.

[26]Xiaoyan Zhou, Christian Wilson, Anthony Limburg, Gireesh Shrimali, Ben Caldecott, Energy transition and the changing cost of capital: 2023 review, Oxford Sustainable Finance Group Report (Oxford, 2023), https://sustainablefinance.ox.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/ETRC-Report-2023_March.pdf.

[27] International Energy Agency, World Energy Investment 2022.

[28] World Bank, World Bank Global Crisis Risk Platform (Washington, D.C.: World Bank Group, 2018), https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/762621532535411008/pdf/128852-BR-SecM2018-0217-PUBLIC-new.pdf.

[29] Michele Catalano, and Lorenzo Forni, Fiscal Policies for a Sustainable Recovery and a Green Transformation, World Bank Policy Research Paper 9799 (Washington D.C.: World Bank, 2021), https://elibrary.worldbank.org/doi/abs/10.1596/1813-9450-9799.

[30] Batini, Nicoletta, Mario Di Serio, Matteo Fragetta, Giovanni Melina, and Anthony Waldron. “Building back better: How big are green spending multipliers?,” Ecological Economics 193 (2022): 107305.

[31] Nicholas Stern and Joseph E. Stiglitz, “Climate change and growth,” Industrial and Corporate Change 32, no. 2 (2023): 277-303, https://doi.org/10.1093/icc/dtad008.

[32] Rupert Way, Mathew Ives, Penny Mealy, and Doyne Farmer, “Empirically grounded technology forecasts and the energy transition”, Joule, Volume 6, Issue 9 (2022): 2057-2082, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joule.2022.08.009.

[33]Nicola Ranger and Michael Mullan, “Adaptation and resilience finance: The role of ‘alignment’ in scaling up adaptation and resilience finance in the Global South” in Scaling Up Sustainable Finance and Investment in the Global South, eds. Dirk Schoenmaker, and Ulrich Volz (London: Centre for Economic Policy Research, 2022), 133-148.

[34] International Energy Agency , World Energy Investment 2022.