Task Force -1: Macroeconomics, Trade, and Livelihoods: Policy Coherence and International Coordination

In recent years, financial inclusion (in terms of its dimensions of access, usage, and quality of products, and services) has increased significantly across nations and regions. However, financial exclusion of certain groups based on gender, age, income, education, and occupation is still rampant in developing economies. These economies, already vulnerable to economic shocks and climate change-related risks due to fragile social, institutional, and regulatory structures, find their resilience further compromised by disparities in financial access and usage. This policy brief draws on the World Bank’s Global Findex Database (2011-2021) to identify and address such gaps within developing economies. It asserts that developing economies require innovative policy interventions, such as enhancing digital infrastructure, introducing novel financial services, fostering financial literacy, consolidating institutions, and strategically leveraging these policies to close gaps in financial inclusion, and adapt to and mitigate climate change-related risks.

1. The Challenge

Financial inclusion is the process of ensuring that people and businesses have affordable, transparent, and sustainable access to the right financial goods and services. It can be incorporated into the broad macroeconomic framework across its three dimensions, that of access, usage, and quality, The last two decades have witnessed rapid development in financial inclusion initiatives across the globe.

Despite progress, about 1.2 billion adults worldwide remain unbanked, lacking an account at a financial institution or access to a mobile money provider.[1],[2] Data also suggest existing gaps in financial access and usage, which are more pronounced in developing economies than in advanced economies.

The gaps in financial inclusion define a state where certain individuals or groups lack universal access to essential financial services such as savings accounts and credit, predominantly due to socioeconomic and individual factors like location, gender, ethnicity, and age. This issue is particularly prominent among certain demographics in developing economies, including those defined by gender, age, income, education, and occupation. For example, women are more likely to be unbanked than men due to limitations in mobility, societal norms, and a lack of official identification. Similarly, younger cohorts may be more unbanked than adults because of lower asset accumulation, fewer opportunities for economic advancement, and increased risk of disengaging from or dropping out of formal education. Significantly, existing gaps can impede the effectiveness of government initiatives aimed at promoting financial inclusion.[3]

Addressing gaps in financial inclusion with strategic policy interventions is crucial, as they hinder financial and social well-being at the individual, household, and macroeconomic levels. Below are outlined the consequences of various forms of financial exclusion:

- Women’s exclusion from the financial ecosystem compromises their empowerment and equality of opportunity.

- Financial exclusion affects the poor and underserved, impacting their educational investment, earnings potential, and economic mobility. This can also impede medium and small enterprises’ access to credit or insurance services, potentially harming start-ups and increasing the levels of unemployment.

- The gap in financial inclusion among younger and older adults restricts the former’s access to government aid during financial distress and complicates decisions on education, employment, and entrepreneurship.

- Adults who have obtained primary education or less face challenges in accessing credit and insurance services or saving for financial uncertainties due to their lack of financial literacy.

- The exclusion of voluntarily or involuntarily unemployed adults adds to their vulnerability and impedes future income and job creation opportunities.

Thus, exclusion based on any individual characteristic compounds the vulnerabilities of those with low income, low resilience, inequality of opportunity, and heightened financial stress. This undermines the objective of financial inclusion.

On a macroeconomic scale, gaps in financial inclusion can impede economic participation of people, exacerbating inequality, poverty, and gender disparities.[4] In addition to these impediments, climate change can increase vulnerability in low-income countries, contributing to increased financial stress.

Climate change-related disasters affect individual livelihoods through the destruction of physical infrastructure, the spread of diseases, loss of income in natural resource-reliant occupations, disruption in educational systems, and rise in food and energy insecurity. The impact is especially severe in vulnerable groups within developing countries (as per the Notre Dame Global Adaptation Initiative index), as they lack the resources to prepare for and recover from extreme weather events.[5] Developing countries also experience inequalities in the impact of climate change-related disasters on marginalised groups, including women, the elderly, ethnic and religious minorities, indigenous people, and refugees.[6]

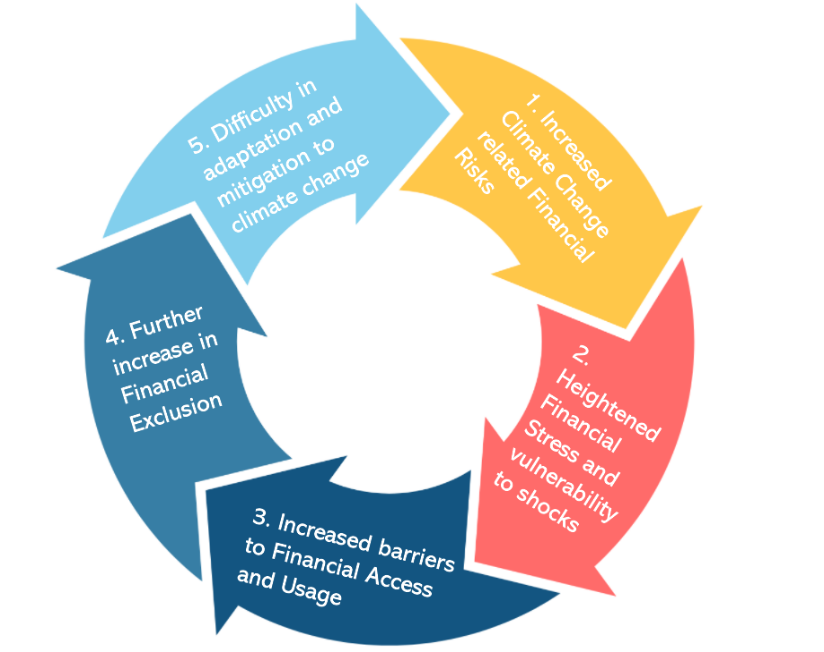

To create an all-inclusive climate-resilient future, it is important to redesign social protection measures such as public works programmes, cash transfers, and social safety nets.[7] Hence, financial services such as insurance, savings, or credit provision assume importance which helps communities build resilience against unexpected shocks and adapt to cleaner technologies.[8] Wide gaps in financial access and usage make it increasingly difficult for low-income countries to adapt to a warmer world.[9] Therefore, it is crucial to close financial inclusion gaps based on demographics and individual characteristics for better adaptation to and mitigation of climate change. The vicious cycle of climate change-related risks and financial inclusion is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Climate Change and Financial Inclusion

Source: Authors’ contribution

Disparities in financial inclusion: Stylised facts

The share of adults with a financial account in the world has increased from 51 percent in 2011 to 76 percent in 2021, thus giving people a safe and convenient way to pay, save, and borrow. This helps build resilience to financial shocks. In developing economies,[a] over the same time period, there has been a 30-percentage point gain in account ownership, bringing the overall adult account ownership rate to 71 percent. Despite improvements, a large proportion of adults in developing economies either do not own an account or also own inactive accounts. In addition, disparities exist in the access, usage, and quality of financial products and services in terms of income, region, gender, education level, and age. These differences are not only significant between developed and developing economies but also among the latter. Financial inclusion gaps are defined in Table 1.

Table 1: Definition of financial inclusion gaps

| Gaps | Definition (adults are defined as the percentage of the population who are 15+) |

| Gender Gap | Percentage difference between female and male adults in financial access, usage, and quality |

| Age Gap | Percentage difference between young (age 15-24) and older (age 25+) adults in financial access, usage, and quality |

| Education Gap | Percentage difference between adults with primary education or less and adults with secondary education or more in financial access, usage, and quality |

| Income Gap | Percentage difference between the poorest 40 percent of adults and the richest 60 percent of adults in financial access, usage, and quality |

| Occupation Gap | Percentage difference between adults out of the labour force and those in the labour force in financial access, usage, and quality |

Source: Authors’ contribution

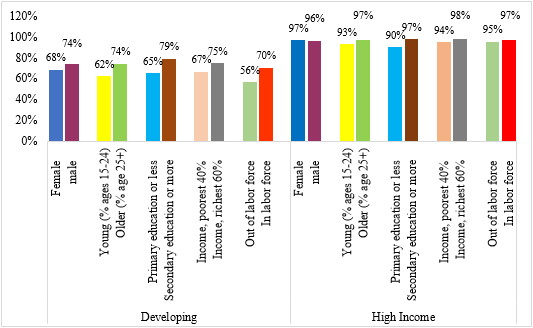

To represent the financial inclusion gaps in access and usage, the chosen parameter of interest is percentage of adults who own an account and the percentage who make or receive digital payments. Figure 2 reveals that 68 percent of women as compared to 74 percent of men own an account in developing economies. 65 percent of adults who obtain primary education or less own an account in comparison to 75 percent of adults who obtain secondary education or more. There is about an eight percent gap between the poorest 40 percent of adults and the richest 60 percent of adults owning an account. A far lesser percentage of unemployed adults in developing countries own an account compared to those who are in the labour force.

Figure 2: Gaps in account ownership among adults (%) by different categories (2021)

Note: The data in the figure refer to the percentage of respondents who report having an account (by themselves or together with someone else) at a bank or another type of financial institution or report personally using a mobile money service in the past year.

Source: Authors’ compilation using Global Findex Database, 2021

Mobile money accounts have been the most important enablers influencing account access and usage in these countries, where the percentage of mobile money accounts has increased from 5.2 percent in 2017 to 12.5 percent in 2021,[10] but only 10 percent of women in developing countries own such an account compared to 15 percent of men.

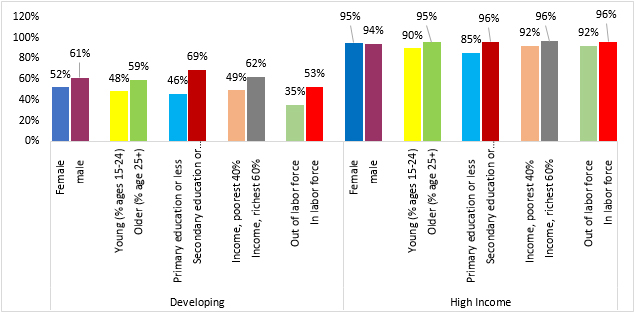

In terms of usage, one of the most popular financial services used is digital payments. The use of digital payments helped small businesses and governments transfer money to the needy in their accounts during the pandemic. Although the share of adults making or receiving digital payments in developing countries increased by 22 percentage points from 2014 to 2021, large variations existed in terms of gender, age, income, education, and occupation between advanced and developing countries and within the latter (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Adults who made or received a digital payment (%) by different categories (2021)

Note: The percentage of respondents who say they have used mobile money, a debit or credit card, a mobile phone, or the internet to pay bills or make purchases online or in stores in the last year is shown in the figure.

Source: Authors’ compilation using Global Findex Database, 2021

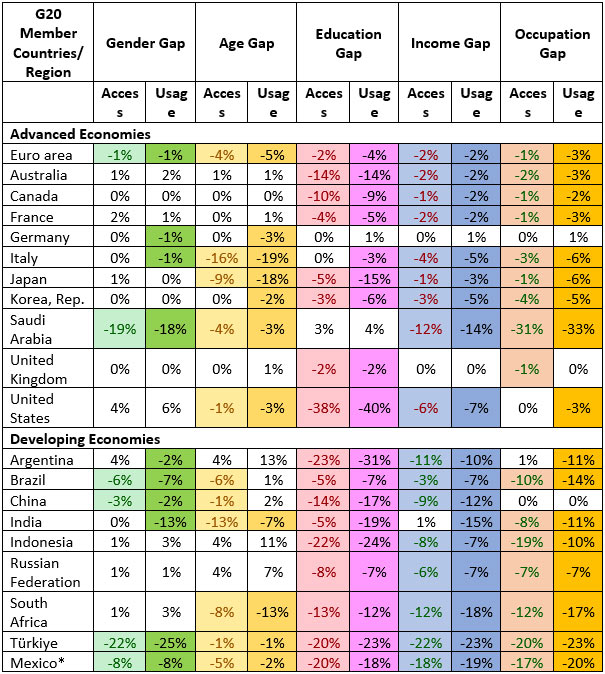

Financial inclusion variations are also analysed by calculating the gaps in the individual characteristics for the G20 countries, as shown in Table 2. For example, Türkiye and Saudi Arabia exhibit large gender gaps in financial access and usage. India exhibits significant gender gap in usage of financial services. Education-based gaps for both financial access and usage exist in both advanced and emerging countries, but percentages are significantly high in Australia, Canada, the US, South Africa, Argentina, China, Indonesia, India, South Africa, and Türkiye (see Table 2). Income-based gaps are visible in most developing and advanced countries, such as Saudi Arabia and the US. There are also significant variations in both access and usage between people not employed in the workforce and those in the labour force, with significantly higher percentages in developing countries.

Table 2: Variations in financial access and usage between advanced and developing economies (2021)

Note: For financial access the parameter of interest chosen is account ownership and for usage the chosen parameter is digital payments made or received. Highlighted cells with different colours represent the different financial inclusion gaps.

* Data for Mexico pertains to 2017 as 2021 data is not available.

Source: Authors’ calculations from the Global Findex Database, 2021.

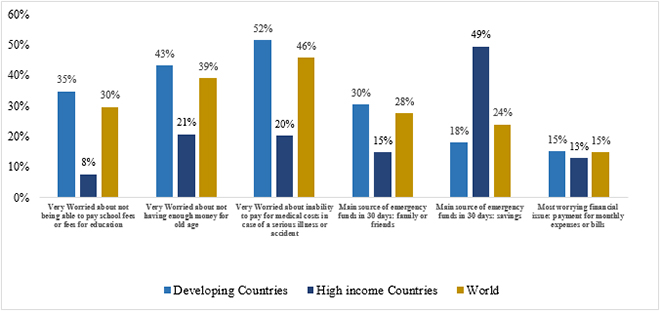

The quality indicator of financial inclusion[b] also suggests lower financial resilience in developing countries. Data reveal that 35 percent of women and 42 percent of the poor in these countries are most likely to be least resilient to economic shocks, as they find it difficult to come up with emergency funds in 30 days (see Figure 4).

Figure 4: Quality indicators of financial inclusion (2021)

Note: The data in the figure refer to the percentage of respondents who reported their primary financial worry about different expenses and also their source of emergency funds.

Source: Authors’ compilation using Global Findex Database, 2021

Developing countries have lower financial resilience than advanced economies, facing greater risk of rising food and fuel prices and more frequent climate shocks. The Notre Dame Global Adaptation Initiative (ND-GAIN)[c] values for the G20 countries show that developed economies have a high degree of readiness and less vulnerability to climate change, while emerging economies exhibit higher vulnerability and lower readiness for climate resilience.

Hence, these disparities highlight the need for customised climate-resilience strategies, with financial inclusion playing a crucial role in empowering vulnerable populations and emphasising the responsibility of more developed nations in supporting global climate resilience efforts.

2. The G20’s Role

The Global Partnership for Financial Inclusion, established in 2010 under the leadership of the G20, along with its implementing partners, aims to enhance coordination for promoting financial inclusion. In 2016, the G20 introduced High-Level Principles to foster digital financial inclusion, tailoring them to individual country contexts. The G20’s commitment to global financial inclusion is also evident through initiatives like the G20 2020 Financial Inclusion Action Plan. Therefore, this group offers a suitable platform to address the financial inclusion gaps in emerging economies.

The G20’s policy toolkit for financial service innovations targeting micro, small, and medium enterprises, coupled with efforts to gather gender-specific data, demonstrates a focused strategy to tackle diverse layers of financial exclusion. This nuanced approach expands financial access to marginalised segments, including women entrepreneurs.

Addressing climate change-related risks and heightened vulnerability requires unified global policy actions to build financial resilience and ensure better adaptation and mitigation to climate-related disasters. The G20’s strategic position facilitates collaborative efforts in this domain.

India’s financial inclusion endeavours, exemplified by the Pradhan Mantri Jan-Dhan Yojana, Stand-up India Scheme, Kisan Credit Card initiative, and the Unified Payments Interface, are founded on a comprehensive approach. These initiatives provide essential public infrastructure and policies that can be adapted to different regulatory and cultural contexts. This adaptability underscores the G20’s capacity to discern financial exclusion nuances and guide policy formulation while also presenting the feasibility of implementing Indian solutions in diverse G20 countries.

3. Recommendations to the G20

To address persistent financial exclusion among certain demographics and to bolster resilience against climate change-related risks in developing economies, a multifaceted approach is needed. Each of the following recommendations provide a direction to the G20 countries to simultaneously address one or multiple financial inclusion gaps.

Strengthening digital financial infrastructure

- Democratising financial access is viable through digitalisation, which enhances ease of transaction, deepens service reach, and reduces providers’ physical barriers.

- Addressing the digital divide in developing economies will include the vulnerable groups in benefits of financial inclusion.

- Promoting competition in the telecom and internet industries can effectively extend the reach of low-cost digital infrastructure.

- Ensuring a responsible digital ecosystem with technical standards, secure cybersecurity, and R&D in digital solutions can strengthen the digital financial infrastructure.

Setting up of better institutions

- Boosting the efficiency of public sector banks will preserve consumer confidence during economic distress.

- Collaboration with private banks, non-profit organisations, and bilateral and multilateral partners will expedite financial inclusion.

- Frameworks for data collection and financial data protection is required for effective policy design, monitoring, and coordination among agencies.

- To address the issue of documentation shortage, a digital national identity such as Aadhaar in India can serve as a bedrock for digital finance.

- An efficient, stable political, and legal system for efficient financial development and citizen participation is required.

- Coordination at regional, national, and international levels must be strengthened to address the issue of financial exclusion.

Fostering innovation in financial products and services

- Tailor-made innovative financial products, which are aligned with community needs, demographics, and regional specificities must be promoted.

- The integration of financial inclusion programmes with health and education priorities can help reduce group disparities.

- Innovative practices such as branchless banking must be utilised to reach the lowest strata.

Enhancing financial literacy

- Digital media such as mobile apps, online courses, and virtual reality should be utilised for more effective financial education programs.

- Information, education, and communication campaigns should be implemented to spread awareness of government schemes aimed at financial inclusion.

- Public education infrastructure can assist targeted groups in understanding the importance of savings and available products.

Addressing affordability and implementation issues

- To combat financial exclusion among women, initiatives should focus on increasing their income by increasing female labour force participation and promoting microfinance.

- Public infrastructure investment in underserved areas can foster private investments in digital finance.

Innovative, inclusive policy interventions to adapt to and mitigate climate change

- Tailored green financial services made accessible to the vulnerable, can encourage environment-friendly practices. This includes green finance for MSMEs and small farmers, regulatory enablers for pay-as-you-go solar and water models[d],[11],[12] and incentives for inclusive green FinTech innovation.

- Access to affordable insurance products for farmers and MSMEs will help cope with income shocks caused by extreme weather conditions.

- Effective public-private partnerships can ensure low-risk and high-impact green financial products for the poor.

- Developing economies can use community service workers model (e.g., Anganwadi workers in India) to educate people to use financial solutions for risks.

Attribution: Pami Dua et al., “Reducing Financial Inclusion Gaps: A Policy Roadmap for Developing Economies,” T20 Policy Brief, August 2023.

Endnotes:

[a] For the current 2024 fiscal year, as per the income classification by World Bank, low-income economies are defined as those with a Gross national Income (GNI) per capita, of US$1,135 or less in 2022; lower-middle-income economies are those with a GNI per capita between US$1,136 and US$4,465; upper-middle-income economies are those with a GNI per capita between US$4,466 and US$13,845; high-income economies are those with a GNI per capita of US$13,846 or more. Low- and middle-income countries are referred to as developing economies.

[b] Financial inclusion is measured in three dimensions: (i) access to financial services; (ii) usage of financial services; and (iii) the quality of the products and the service delivery.

[c] ND-GAIN is a programme of the University of Notre Dame’s Environmental Change Initiative. T This Country Index ranks 181 nations each year according to their vulnerability as well as readiness for successful adaptation using data from two decades across 45 indicators High values of this index represent high degree of readiness of a country to improve resilience and hence lesser vulnerability to climate change and vice versa.

[d] Pay as you go (PAYGO) services give customers access to environment-friendly technologies such as solar and other alternative power sources where they can take a small loan to buy power from an off-grid solar panel, and then pay it off in instalments through mobile money accounts.

[1] Asli Demirgüç-Kunt, Leora Klapper, Dorothe Singer, and Saniya Ansar, The Global Findex Database 2021: Financial Inclusion, Digital Payments and Resilience in the Age of COVID-19 (World Bank: Washington, DC).

[2] World Bank, The Little Data Book on Financial Inclusion 2022, World Bank, 2022, Washington DC.

[3] Peterson K. Ozili, “Theories of Financial Inclusion,” in Uncertainty and Challenges in Contemporary Economic Behaviour, ed. Ercan Özen, and Simon Grima, (Emerald Publishing, 2020), 89-115.

[4] Cyn-Young Park and Rogelio Mercado, Financial Inclusion, “Poverty, and Income Inequality in Developing Asia,” ADB Economics Working Paper Series, No. 426, (Asian Development Bank, Manila).

[5] Sophie Sirtaine and Claudia Mckay, “In an Era of Urgent Climate Risk, Does Financial Inclusion Matter?”, CGAP Leadership Essay Series, June 2022.

[6] Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability, IPCC, 2022, Geneva.

[7] Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report, IPCC, 2023, Geneva.

[8] Innovations for Poverty Action, Climate Change and Financial Inclusion, IPA, 2017,

[9] Pierpaolo Grippa, Jochen M. Schmittmann, and Felix Suntheim, “Climate Change and Financial Risk,” Finance & Development, December 2019.

[10] Demirguc-Kunt, Klapper, Singer, and Ansar, The Global Findex Database 2021.

[11] B. Kelsey Jack and Grant Smith, “Pay as You Go: Prepaid Metering and Electricity Expenditures in South Africa,” The American Economic Review 105, no. 5 (2015), 237-241.

[12] Gerge Adwek et al., “The Solar energy access in Kenya: a review focusing on Pay-As-You-Go solar home system,” Environmental Development and Sustainability 22 (2020),3897–3938.