TF-6: Accelerating SDGs: Exploring New Pathways to the 2030 Agenda

Gender equality and women’s empowerment are important targets of the Sustainable Development Goals. Boosting female participation in the workforce is necessary to achieve both these objectives. In 2014, the G20 leaders agreed to cut the gender gap in labour force participation by 25 percent by 2025. Reports show that in almost all G20 countries, female participation in the workforce increased till 2019,[1] but the COVID-19 crisis has derailed this progress. This policy brief advocates for women’s economic independence by encouraging their participation in social entrepreneurship. While acknowledging the diverse social and cultural dynamics influencing women’s participation in the labour force, this policy brief primarily focuses on addressing the crucial issue of limited funding for women social entrepreneurs across all G20 nations. In alignment with these objectives, this brief proposes the establishment of a G20-wide ‘Social Stock Exchange’ to provide logistical benefits to international investors and facilitate financial support for women-centric social enterprises. The creation of such a platform can accelerate the integration of women in the workforce and help combat the adverse effects of gender inequality on the global economy.

1. The Challenge

Empowering and providing equal opportunities to women while fostering an inclusive work environment are crucial for achieving sustainable economic growth. This is highlighted in goals 5 and 8 of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) Currently, the rate of women’s participation in the global labour force is slightly below 47 percent, while for men, it is 72 percent.[2] Women’s labour force participation rate in some G20 countries is alarmingly low. For instance, India’s rate is 23 percent, Saudi Arabia’s is 28 percent, Türkiye’s is 33 percent, and Italy’s is 40 percent.[3] Looking at it economically, reducing gender disparities in labour force participation has the potential to significantly increase the global GDP.[4],[5] The underrepresentation of women in the labour force can be attributed to a complex interplay of social and cultural factors, which shape and constrain opportunities for women’s economic engagement. However, certain major challenges persist across many G20 countries, including:

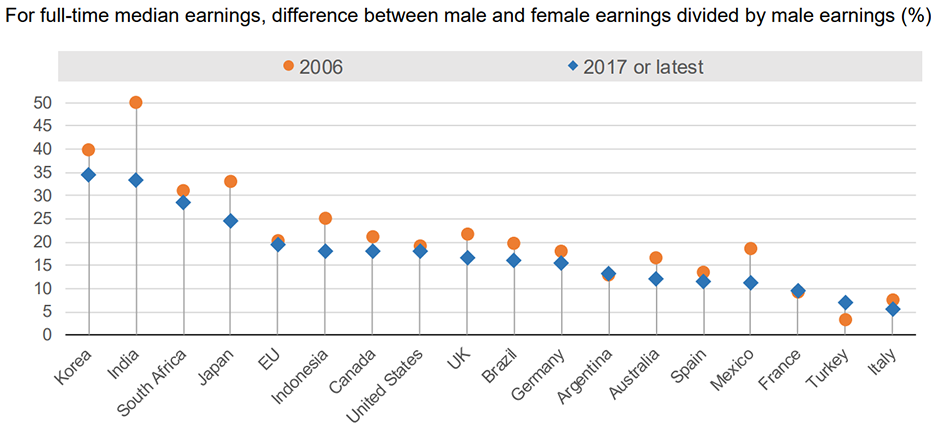

- Unequal pay: In all the G20 economies, women are paid less than men on average. When it comes to the median earnings of full-time workers, women earn between 30-35 percent less than men in India and Korea.[6] However, in France, Turkey, and Italy, the pay gap is much smaller i.e., 10 percent or less (see Figure 1). Moreover, in many nations, the difference in pay between men and women is even more significant when adjusted for gender-based differences in paid work, such as educational attainment[7] (see Figure 2). This becomes a major impediment to ensuring female participation in the workforce. Reducing the pay gap is crucial for improving female participation in the workforce as it would provide women with greater economic security and incentivise them to participate more actively. It would also promote gender equality, leading to a more diverse and inclusive workforce.

Figure1: Gender pay gaps in G20 nations (2006 to 2017)

Note: The earliest available data for South Africa is from 2008. The most recent available data for India is from 2012; for EU, France, Spain, and Türkiye is from 2014; for Brazil and South Africa is from 2015; and for Italy and Germany is from 2016. Data for China and Russia is not provided.

Source: ILO and OECD.[8]

Figure2: Gender pay gaps in G20 nations (2012 to 2019)

Note: The earliest available data for France, Germany, Italy, Spain, and Türkiye is from 2010; for South Africa is from 2013, and for South Korea is from 2014. The most recent available data for France, Germany, India, Italy, South Africa, Spain, and Türkiye is from 2018. Data for China and Russia is not provided.

Source: ILO and OECD.[9]

- Gender disparity in employment: Gender disparity in employment refers to the difference in employment rates between men and women. Women routinely experience unequal opportunities and treatment in the work market. Barriers to entry and progress are more likely to affect women. Women who want to work often struggle more than men to find gainful employment.[10] The unemployment rate for women is still higher than the rate for men in about half the G20 economies.[11] The gender gap in employment rate is at 4.2 percent in Argentina, 5.8 percent in Brazil, 2.5 percent in Italy, 3.9 percent in South Africa, 3.3 percent in Turkey and a whopping 17.9 percent in Saudi Arabia.[12]

- Impact of COVID-19 crisis: Substantial progress was reported in the participation of women in the workforce across the G20 nations before the COVID-19 pandemic. However, gender inequality in the workforce was exacerbated as a result of the pandemic. For women, the loss in income was around US$800 billion, which equals to the combined GDP of more than 98 countries.[13] Women’s jobs were seen to be 1.8 times more vulnerable during this crisis as compared to men.[14] Globally, even though women make up 39 percent of employment, they accounted for 54 percent of all job losses during the COVID-19 crisis.[15] After the pandemic, one in four women are contemplating leaving the workforce as compared to one in five men.[16] Globally, women lost 64 million jobs in 2020, a 5 percent loss in employment as compared to 3.9 percent for men.[17] Even in most G20 nations, women were disproportionately hit by job and working-time losses.[18] In countries like Canada, Mexico, Spain, and the UK, employment of women in the workforce in 2021 remained well below pre pandemic levels .[19] Similarly, in terms of number of hours worked, women faced a greater shortfall than men in many G20 nations, especially in Canada, Mexico and Spain.[20]These alarming statistics reflect that the economic fallout of the pandemic is harsher on women than men. This could be because of a number of reasons. Women are majorly employed in informal and precarious sectors like retail, tourism, and food services and often receive much lower salaries. These sectors have been hit more severely by the pandemic as compared to the rest. In said sectors, women not only experienced job losses but also reductions in working hours and income.[21] It is, therefore, evident that even though significant progress was reported by G20 nations in closing the gender gap in workforce participation in the pre-pandemic era, the COVID-19 pandemic and its effects threaten to reverse the gains achieved.

- Challenges faced by social enterprises: Women social entrepreneurs face multi-faceted challenges. Female owned businesses are generally smaller, grow less rapidly, and close down during the initial years due to lack of funding.[22] This problem also stems from the fact that there is lack of financial services and initiatives geared towards women. Less than 40 percent of women in G20 countries have access to bank accounts, which makes access to credit difficult for them.[23] The Covid-19 crisis has further aggravated the problem of credit for women-led enterprises due to bankruptcies. Attracting investment is one of the major problems faced by social entrepreneurs.[24] Both male and female social entrepreneurs worry about having access to sufficient financing, but there do appear to be extra obstacles for women.[25] According to a WeStart study, which focusses on women social entrepreneurs in Europe, the most significant obstacle they face is the lack of access to funding.[26]

2. The G20’s Role

The G20 is a significant forum that works to address global economic concerns. The countries that make up the G20 represent 85 percent of global GDP, over 75 percent of global commerce, and around two-thirds of the world’s population.[27] As a result, the G20 has a special chance to lead initiatives that raise female labour force participation, lessen gender inequality, and accelerate economic growth. The G20 has already taken certain measures to promote greater gender equity in the workforce. The G20 leaders agreed to close the gender gap in labour force participation by 25 percent by 2025 at their Brisbane summit in 2014.[28] A roadmap was then requested at the Riyadh summit in 2020 to ensure success in both lowering the gender gap in labour force participation as well as raising the standard of women’s employment. Consequently, several G20 nations have enacted more lenient parental leave policies, pay transparency regulations, increased minimum wages, and policies to stop and address workplace harassment and violence against women. However, most of the emergency measures implemented in response to the COVID-19 pandemic have been gender-neutral, necessitating further interventions to hasten the process of meeting the Brisbane objective and enhancing the quality of jobs for women.[29]

India’s G20 presidency comes at a very crucial time when the world economy is recovering from the ill effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and there is an increased need for women to enter the labour force. The G20 countries could work together on policy initiatives to address the unique difficulties faced by women in various situations, such as those who have young children, have worked in pandemic-affected industries in the past, are in poor mental health, and experience physical and verbal abuse or harassment. Ultimately, increasing women’s participation in the labour force and improving the quality of their employment are essential for achieving sustainable economic growth and meeting the UN’s SDGs. The G20 countries have a special chance to lead international efforts in this area. Policy measures and collaboration on tackling issues encountered by women can help speed up progress towards attaining the Brisbane target and improving employment opportunities for women.

3. Recommendations to the G20

The challenge of gender disparity in workforce participation can be mitigated by promoting the participation of women in social entrepreneurial activities. However, as mentioned earlier, funding and outreach remains a major issue in this regard. To tackle this, the establishment of a G20-wide ‘Social Stock Exchange’ (SSE) can be a potential solution. By bridging the gap between capital providers and businesses pursuing social welfare goals, the SSE allows for socially conscious investing.[30] An SSE’s purpose is to serve as a forum for both social enterprises and investors whose goals and interests are similar to one another.[31]

Essentially, a social enterprise is a business that places as much importance on achieving social good as it does on generating profits. Its overall goal is to create a more equitable economy. Reports suggest that self-employment can be a useful way to boost employment opportunities for women. According to the World Bank, women-lead social enterprises can contribute towards sustainable development and poverty reduction.[32] Studies also suggest that the global economy could be boosted by US$5 trillion by closing the gender gap that exists in entrepreneurship.[33] Promotion of social entrepreneurship among women can create workplaces that are more equitable and supportive of women employees. It will help women gain equal pay and access better work conditions. It will also help create businesses that provide training and development opportunities so that women can acquire the skills and knowledge needed to succeed in high-paying industries. By providing women access to such opportunities, G20 nations can help bridge the skills gap between men and women and enable women to access better-paying jobs. Women-led social enterprises can also encourage female employees to learn by example and take on leadership roles.

Social enterprises not only help women gain economic independence but also help them overcome many social and cultural barriers. By becoming social entrepreneurs, women also gain respect within their families.

For example, a woman from Maharashtra faced domestic violence and demands for dowry. However, after she became an entrepreneur through wPOWER India Project, she was able to overcome her financial and domestic struggles running a profitable business selling solar products in her community.[34]

Therefore, to promote the establishment of women-centric social enterprises, a G20-wide SSE needs to be formulated. By establishing it as per the specific needs and mechanisms of the member countries, the G20 can finance swomen-led ocial enterprises and/or those that provide livelihood to women. Social enterprises present a huge opportunity to support women’s empowerment. According to research, there is also great potential to enhance the quantity and effectiveness of social enterprises that prioritise women’s empowerment.[35] Although numerous autonomous social enterprises are already operating in this field, they lack exposure and networking opportunities

Financing women entrepreneurs

Financing remains a significant issue for women-led enterprises. Raising funds is routinely hindered by social and cultural biases against women. Women-led social enterprises are often denied funding as they are considered riskier investments, and this is especially true in case of women who are from underprivileged socio-economic backgrounds, with lower levels of education.[36]

For example, a women entrepreneur in Jaipur was denied a loan by a private bank until her husband co-signed her application. Similarly, a woman entrepreneur in Bhopal was criticised by potential funders for wearing Western clothes rather than Indian.[37] Thus, lack of access to funds remains a major problem for women entrepreneurs.

This challenge can be solved by financing women-centric social enterprises through the G20-wide SSE. Gender segmentation strategy can be adopted to finance such social enterprises under an SSE. This would make it easier for investors to identify social enterprises that align with their investment goals. Moreover, member nations of the G20 can play a vital role in promoting and raising awareness about women-centric social enterprises. Promotional programmes could include media coverage, seminars, workshops, and conferences to showcase the work of these social enterprises. Apart from gender, segmentation could also be based on type of enterprise, industry, size of enterprise, and location.

With the availability of funds, social enterprises that focus on women can experience substantial expansion in their business operations, leading to the development of more employment opportunities for women and their economic empowerment. Additionally, this expansion could entice a larger pool of investors and financing to the SSE, thereby building a sustainable ecosystem for women-centric social enterprises.

Working mechanism

The G20’s Sustainable Finance Working Group can take up the task of investigating and proposing suggestions regarding potential systems and methods that fall under the securities market category, which could assist social enterprises and voluntary organisations in gathering funds. Since India recently launched its national SSE under the regulatory ambit of the Stock Exchange Board of India, it can guide the establishment of a G20-wide SSE.

- Definition of ‘social enterprise’: An organisation should be classified as a social enterprise only if it engages in the business of creating a positive social impact in society. Both non-profit organisations (NPOs) and for-profit organisations (FPOs) should be eligible to be recognised as asocial enterprises as long as they fulfil the same criteria. To ensure that only genuine organisations are able to join the SSE, it is suggested that the G20 countries, in consultation with the Sustainable Finance Working Group, develop a mechanism for evaluating the credentials as well as social impacts of different organisations.

- Differential treatment of non-profit and for-profit organisations: Since NPOs and FPOs raise different kinds of capital, it is advisable for them to be treated differently. This will also help investors manage their portfolio accordingly.

- Mandatory registration and monitoring of organisations: Registration of all organisations in the SSE should be mandatory to avoid any form of violation of the SSE’s provisions. Additionally, the organisations should be monitored so that their social impact (as advertised by them) is duly measured and ascertained. To tackle this, the SSE should conduct yearly social audits. This exercise should only be undertaken by independent auditing bodies called a self-regulatory organisations (SRO).

- Identification and establishment of self-regulatory organisations: The Sustainable Finance Working Group can play a key role in identifying and establishing SROs in all G20 member nations. This would ensure that independent auditing organisations are in place to conduct social audits and monitor the organisations’ compliance with social impact standards. It is pertinent to ensure that the SROs audits are limited only to cross-country social enterprises that lack similar mechanisms. This would make the implementation far more transparent and accountable.

Attribution: Priyanshu Agarwal and Aaiysha Topiwala, “Promoting Women’s Participation in the Labour Force: The Case for a G20-Wide Social Stock Exchange,” T20 Policy Brief, July 2023.

Endnotes

[1] International Labour Organization and Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Women at Work in G20 countries: Progress and policy action since 2019, Saudi Arabia, ILO and OECD, 2020.

[2] “ILO Modelled Estimates and Projections database (ILOEST),” International Labour Organisation, accessed February 21, 2023.

[3] ILO, ILOEST.

[4] “World Employment and Social Outlook: Trends for women 2017,” International Labour Organisation, accessed February 21, 2023.

[5] ILO, World Employment and Social Outlook: Trends for women 2017.

[6] ILO and OECD, Women at Work in G20 countries

[7] ILO and OECD, Women at Work in G20 countries

[8] ILO and OECD, Women at Work in G20 countries

[9] ILO and OECD, Women at Work in G20 countries

[10] “The gender gap in employment: What’s holding women back?,” International Labour Organisation, accessed February 21, 2023.

[11] ILO and OECD, Women at Work in G20 countries

[12] “ILO Modelled Estimates (ILOEST database), November 2021,” International Labour Organisation, accessed February 21, 2023.

[13] “COVID-19 cost women globally over $800 billion in lost income in one year,” OXFAM International, accessed March 30, 2023.

[14] Anu Madgavkar, Olivia White, Mekala Krishnan, Deepa Mahajan, and Xavier Azcue, “COVID-19 and gender equality: Countering the regressive effects,” McKinsey & Company, March 30, 2023.

[15] Madgavkar, White, Krishnan, Mahajan, and Azcue, “COVID-19 and gender equality: Countering the regressive effects”

[16] “Seven charts that show COVID-19’s impact on women’s employment,” McKinsey and Company, last modified March 8, 2021.

[17] OXFAM International, “COVID-19 cost women globally over $800 billion in lost income in one year”

[18] ILO and OECD, Women at Work in G20 countries

[19] ILO and OECD, Women at Work in G20 countries

[20] ILO and OECD, Women at Work in G20 countries

[21] Courtney Connley, “In 1 year, women globally lost $800 billion in income due to Covid-19, new report finds,” CNBC, March 30, 2023.

[22] ILO and OECD, Women at Work in G20 countries

[23] Beena Pandey, “Moving Ahead for Women Empowerment in G20,” G20 Digest, 39-50.

[24] Svetlana Boguslavskaya and Ilyana Demushkina, “Social stock exchange a new socio-economic phenomenon,” Paper presentation, 2013.

[25] British Council, Activist to entrepreneur: The role of social enterprise in supporting women’s empowerment, British Council, 2023.

[26] “We are changing the way Europe does business. We are women social entrepreneurs,” WEstart, accessed March 30, 2023.

[27] “The Group of Twenty (G20),” india.gov.in, accessed March 30, 2023.

[28] “Brisbane, Australia, 15-16 November 2014,” OECD, accessed March 30, 2023.

[29] ILO and OECD, Women at Work in G20 countries

[30] “Framework for Social Stock Exchange,” Securities and Exchange Board of India, accessed March 30, 2023.

[31] Charles Ambrose et al., “A Study on the Scope of Implementation of Social Stock Exchange in India,” Turkish Online Journal of Qualitative Inquiry (TOJQI) 12, no. 8 (July 2021): 323-339.

[32] Eliana Carranza, Chandra Dhakal, and Inessa Love, “Female Entrepreneurs: How and Why Are They Different?” WBG JOBS WORKING PAPER, no. 20 (Washington, DC: World Bank Group, 2018).

[33] Shalini Unnikrishnan and Cherie Blair, “Want to boost the global economy by $5 trillion? Support Women as Entrepreneurs,” Boston Consulting Group, March 30, 2023.

[34] “How to Support Women Social Entrepreneurs in India,” Stanford Social Innovation Review, modified March 14, 2018.

[35] British Council, Activist to entrepreneur

[36] British Council, Activist to entrepreneur

[37] Stanford Social Innovation Review, How to Support Women Social Entrepreneurs in India.