Task Force 7: Towards Reformed Multilateralism: Transforming Global Institutions and Frameworks

There is a growing risk that geoeconomic fragmentation will lead to real income losses across the world of about 2 percent of GDP, with the losses in the Middle East, Central Asia, and Africa more than twice those of advanced economies. In this context, multilateral cooperation is more important than ever to address the world’s growing challenges, which are transnational and beyond the capacity of any single country or organisation. This policy brief explores two recent examples of state and non-state actors being able to build cooperation in a fragmented world—the World Investment for Development Alliance (launched in May 2022), and the World Trade Organization Agreement on Investment Facilitation for Development that is about to be concluded. The brief will suggest some initial lessons from both to potentially increase G20 coordination and cooperation in other areas, arguing for the primacy of a facilitative approach (i.e. improvements in the system’s efficiency through better information, speeding up procedures, and lowering costs) in the context of significant policy divergence.

1. The Challenge

Friendshoring may go down in history as the most consequential word of 2022. In April 2022, US Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen stated, “Friend-shoring means—and you’ve seen this in action—that we have a group of countries that have strong adherence to a set of norms and values about how to operate in the global economy and about how to run the global economic system, and we need to deepen our ties with those partners”.[1]

Six months later in October 2022, Chrystia Freeland, deputy prime minister of Canada and minister of finance, echoed the view, “Replicated across the world’s democracies, friend-shoring is an historic opportunity for our workers and our communities… it is an economic opportunity to attract new investment, create more good-paying jobs, and thrive in a changed global economy. It can make our economies more resilient, our supply chains true to our most deeply held principles, and protect our workers and the social safety net they depend on from unfair competition created by coercive societies and race-to-the-bottom business practices”.[2]

The trouble with friendshoring is that it comes with costs. It is important both to acknowledge this and try to minimise them. Recent analysis by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) provides to date the best estimates of these costs, considering both trade and especially investment.

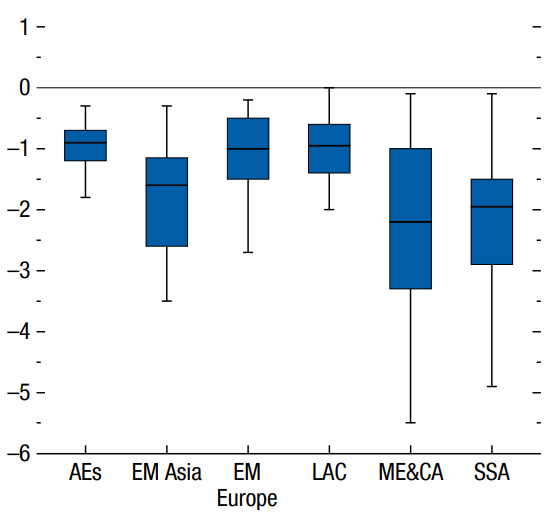

In terms of geoeconomic fragmentation and trade, real per capita income may fall by as much as 2 percentage points in a ‘tripolar’ world with a US bloc, a China bloc, and a non-aligned bloc.[a] IMF estimates find that a rise in trade barriers is more damaging to smaller economies (in terms of population and GDP), which tend to rely more on international trade; that trade barriers are more damaging to countries that import from sensitive sectors; and that fragmentation is more damaging for those countries that are non-aligned.[3] See figure 1 for the estimates of GDP loss across different economic groups.

Figure 1. Change in real per capita income due to trade fragmentation (percentage)

Source: IMF World Economic Outlook[4]

Note: The horizontal lines stand for the medians, the box represents the 25th and 75th percentiles, and the whiskers represent the extremes, excluding outliers. AEs = advanced economies; EM = emerging and developing; LAC = Latin America and the Caribbean; ME&CA = Middle East and Central Asia; SSA = Sub-Saharan Africa.

Before looking at the estimates of GDP loses from geoeconomic fragmentation through the channel of greater barriers to FDI, first consider estimates of the effect of geoeconomic fragmentation on FDI flows.

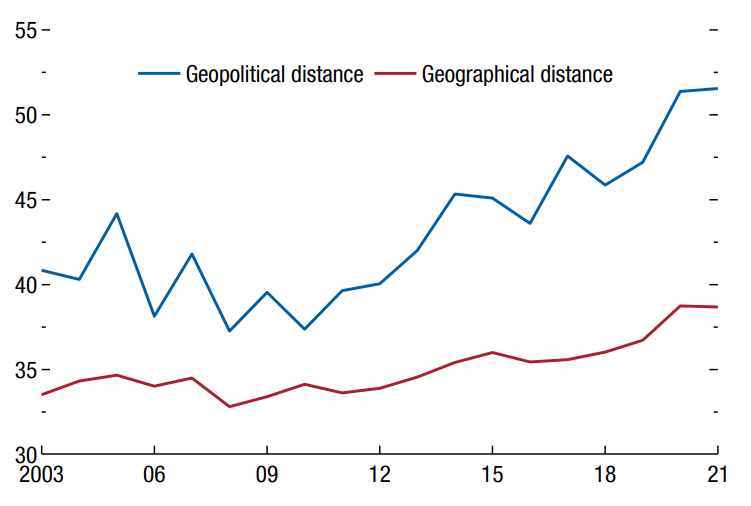

Figure 2 shows the annual share of total foreign direct investments between country pairs that are similarly distant geopolitically and geographically, from the US. The importance of geopolitical distance as a determinant of FDI received has clearly shot up over the last few years.

Figure 2. FDI between geographically and geopolitically close countries (percent)

Source: IMF World Economic Outlook[6]

Figure 3. FDI fragmentation: FDI flows in strategic sectors (number of investments received)

Source: JaeBin Ahn, Ashique Habib, Davide Malacrino , Andrea F. Presbitero[7]

Figure 4. Interest in reshoring and firm characteristics (percent of total by type of firm)

Source: IMF World Economic Outlook[8]

Note: Simple averages across firms that mentioned or did not mention reshoring, friend-shoring, and near-shoring in earnings calls. Differences across groups are statistically significant. EBIT = earnings before interest and taxes.

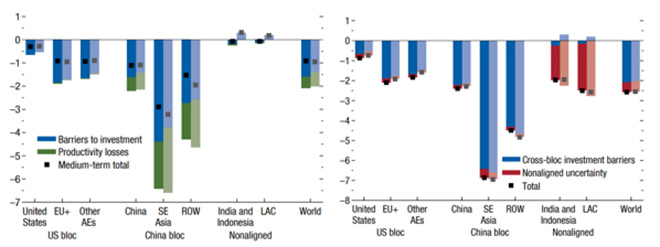

Figure 5. Impact of FDI barriers on GDP [percent deviation from no-fragmentation scenario, short-term (left figure) vs long-term (right figure)]

Source: IMF World Economic Outlook[9]

Note: AEs = advanced economies; EU+ = European Union and Switzerland; LAC = Latin America and the Caribbean; ROW = rest of the world; SE = Southeast.

Aiyar and Ilyina (2023), citing Aiyar et al. (2023), provide a review of four other studies.[10] They report that each study makes stlightly different assumptions about the nature of fragmentation, the composition of geopolitical blocs, the types of barriers imposed between blocs, and elasticities of substitution among suppliers. In each case, the authors also consider different scenarios. However, notwithstanding this heterogeneity, the authors identify some common findings:

- The costs are greater the deeper the fragmentation;

- Reduced knowledge diffusion due to technological decoupling is a powerful amplifier of the trade channel;

- Emerging markets and low-income countries tend to be most at risk from trade and technology fragmentation;

- Transition costs are likely to be considerable; and

- Estimates should not be taken as an upper-bound, since they do not reflect the possible impact through the combined effect of several geo-economic fragmentation transmission channels.

The challenge is clear and worrying. The gains from trade and investment that have helped bring about growth in prosperity over the past decades are at risk. At the same time, while lowering GDP, friendshoring may nevertheless help address issues of risk and values, with those who increasingly trade and invest with each other at a lower chance of trade and investment disruptions given their political alignment.

Is there a way to reconcile these competing objectives of growth and resilience?

This policy brief will argue that two recent examples of multilateral cooperation may provide some insight to facilitate cooperation even amidst political challenges. Nascent cooperation over investment—and how it was brought about—may hold lessons that might be useful for other efforts at fostering multilateral cooperation in a multipolar world.

2. The G20’s Role

The G20 has a long tradition of working on investment policy and practice. To cite just a few examples, the G20 has tasked international organisations with reporting on investment measures adopted by G20 economies, and these reports have appeared twice a year since September 2009, for a total of 28 editions to date. In September 2016 at the Hangzhou Summit, G20 leaders endorsed ‘G20 Guiding Principles for Global Investment Policymaking’, a significant achievement. More recently, the G20 tasked the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) with mapping G20 and other economies’ investment measures linked to sustainable development, producing the ‘G20 Compendium on Promoting Investment for Sustainable Development’, better known as the ‘Bali Compendium’. The G20 Bali Leaders’ Declaration mentions the word ‘investment’ 1,332 times.

The G20, therefore, clearly cares deeply about and has commissioned extensive work on investment policy and measures.

How can the G20 help reconcile the competing goals of resilience through friendshoring and the benefits of FDI flows for growth? At first glance, these seem to be diametrically opposed, a zero-sum game.

However, there may be a small conceptual space that reconciles the two through focusing on investment facilitation. In other words, to minimise frictional costs to policy implementation in terms of time and uncertainty, rather than focus on FDI market access directly. By focusing on facilitation—a non-political approach—efficiencies in the system can be maximised, and in so doing maintain the flows of investment as much as possible within the constraints friendshoring policy changes.

The benefits of focusing on facilitation can be seen through two successful multilateral or pro-multilateral initiatives in the area of investment that have recently emerged.

The G20 can review the lessons below that helped stand up these two initiatives and perhaps consider if these lessons could be usefully applied to other areas to foster cooperation over technical issues even amidst geoeconomic rivalry over political issues. For instance one candidate could be ‘e-commerce facilitation’. Negotiations are underway at the World Trade Organization (WTO) on a Joint Statement Initiative on E-Commerce, but have been bogged down by significant differences on policy issues. However, a way forward seems to advancing through a facilitative approach that separates the technical issues from the thorny, policy issues and tackles the former. There may be other areas related to technology, security, and science, to name just a few, where a facilitative approach may also be useful.

3. Recommendations to the G20

· World Investment for Development Alliance

On 24 May 2022, the World Investment for Development Alliance (WIDA) was launched at the World Economic Forum’s annual meeting in Davos.[11] This was the culmination of little under a year of preparatory legwork initiated by the UNCTAD and the World Economic Forum. The 10 founding organisations were the Academy of International Business, African Union Commission, International Institute for Sustainable Development, International Trade Centre, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, UNCTAD, United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific, World Association of Investment Promotion Agencies, World Bank Group, and the World Economic Forum. Organisations with similar capacity were welcomed to join, and since the International Labour Organization, the United Nations Industrial Development Organization, and the World Tourism Organization have done so, with the WTO becoming an observer.

WIDA is a global platform dedicated to promoting investment for sustainable development. WIDA pursues this overarching objective by creating synergies and maximising impact through joint advocacy, joint organisation, and joint actions among participating organisations. It meets quarterly with the aim of sharing information, coordinating activities, and fostering collaboration.

How did WIDA come to exist, and what lessons may be relevant to the G20 and other actors? A founding group was first created to allow for dialogue among a more limited group of actors, even though many organisations were relevant and active in the area of investment for development, as well as a core group to help with executive action to move things forward. At the same time, care was given to ensure that founding organisations contained representatives of different types of organisations from different geographies to create balance and ensure different perspectives would be reflected.

The group decided to adopt an initially light-touch approach that could be deepened and scaled over time if needed, minimising bureaucracy and resource needs and requests.

In addition, to determine the areas on which to focus collaboration and cooperation, the first step was to carry out a mapping of activities of participating organisations. This allowed the identification of areas where there was greatest convergence of activities and thus where cooperation might be most useful, as well as areas of relatively fewer existing activities where there were gaps that could be addressed jointly.

What emerged from the mapping was investment facilitation as the area with the greatest convergence, and so WIDA decided to include a standing agenda item on investment facilitation during its quarterly meetings, as well as to survey WIDA organisations on investment facilitation activities to develop and circulate a ‘compilation of investment facilitation activities by wida organisations’ ahead of the meeting to inform discussion.

The aim was, at a minimum, to share information so that all knew what others were doing or planned to do. This could naturally translate into better coordination, and then, into facilitating cooperation.

For instance, the ongoing aim is to support coordination in the delivery of investment facilitation country projects to avoid multiple projects in one country and some countries receiving little if no technical assistance in this area; coordinating technical assistance to help implement key investment facilitation measures to avoid multiple organisations supporting the same measures but rather—in the aggregate—helping cover many different measures; and building on each organisation’s work to not duplicate earlier outputs but rather use of these earlier outputs by other organisations, thereby stretching finite resources to cover more countries and more measures.

What lessons can the G20 learn from this new alliance to foster multilateral cooperation in a multipolar world? The takeaway is to approach things gradually, with incremental steps, and to focus on facilitation. Not only was this the area with the greatest convergence in terms of existing and planned activities, but it was also a technical area that seeks to improve efficiency in the system, rather than a policy area that seeks to provide, for instance, market access or investment protection.[c]

This is the very same principle (focusing on facilitation and not thorny, controversial topics like market access, investment protection, or investor-state dispute settlement) that has allowed for a WTO Agreement on Investment Facilitation for Development to come to a successful conclusion,.

· WTO Agreement on Investment Facilitation for Development

An Agreement on Investment Facilitation for Development (IFD Agreement) has almost been concluded by over 110 economies at the WTO, with the text-based negotiations having been completed. The new agreement will create binding disciplines on parties to adopt investment facilitation measures that will strengthen their investment climate, and in so doing should increase investment flows and their development benefits. Global welfare could increase by up to US$1.1 trillion (or by between 0.56 percent and 1.74 percent of GDP).[12]

Examples of commitments in the IFD Agreement include transparency on rules, streamlining of regulations, coordination between and within economies, and innovative instruments such as supplier development programmes and supplier databases to increase capacity and help match capital with firms.

The significance of this new agreement is that it creates a common roadmap to strengthen investment climates and a framework for cooperation, both government-to-government and government-to-investor.

It is important to clarify that the conclusion of text-based negotiations does not mean that the agreement will soon enter into force, as certain members have expressed opposition to plurilaterals, or ‘pro-multilateral’ agreements,[d] incorporated into the WTO architecture. Nevertheless, resolution of the remaining substantive issues in the negotiation process is a milestone.

The question then is, how were these negotiations successful, and what lessons may be draw from over 110 economies reaching a ‘pro-multilateral’ outcome?

Together, the examples of IFD and WIDA, show that multilateral cooperation can most fruitfully, at present, be grounded in a facilitative approach. In other words, this means removing most of the controversial issues from the scope of discussion and focusing on technical solutions to improve systemic efficiency.

Other lessons from the IFD process include collecting and amalgamating economies’ and international organisations’ experiences of important and impactful investment facilitation measures as a starting point to create a agreement, thereby drawing from experiences of practitioners; welcoming input from practitioners with real-world experience in investment facilitation, both firms and investment promotion and facilitation authorities; placing issues where there is lack of consensus on a future work programme to avoid holding back finalisation of the agreement; and creating a committee to exchange experiences regarding implementation and monitor whether the agreement is effective in practice.

These two separate initiatives in the area of investment—including some, if not all, G20 members—have shown that multilateral cooperation is still possible if a facilitative approach is adopted.

In other words, the first step to fostering multilateral cooperation in a multipolar world is to focus on improving the efficiency of the system rather than trying to change policies of leading economies. There is still a lot of multilateral cooperation that can take place when focusing on improving the efficiency of the system, including on speeding up time, lowering costs, sharing information, harmonising standards, modernising technological systems, and supporting coordination among actors.

Both WIDA and the IFD Agreement have provided real-life examples of actors coming together to coordinate and cooperate on investment facilitation. Based on these experiences, the G20 economies may wish to focus on bringing a facilitative approach to other issues whether progress may initially seem elusive. A clear candiate could be e-commerce, where negotiations at the WTO are bogged down by policy differences. Other candidates where a facilitative approach may be useful amidst thorny issues could include technology, and security and science policy.

Building some cooperative momentum through focusing on facilitation may gradually then grow to tackling the substantive issues facing out multipolar world.

Attribution: Matthew Stephenson, “Multilateral Cooperation in a Multipolar World: What Can We Learn from Investment?,” T20 Policy Brief, June 2023.

Endnotes

[a] In the model countries are assigned to blocs based on whether their current geopolitical treaties are stronger with the US, stronger with China, or equally strong with both.

[b] The list used comprises semiconductors, telecommunications and 5G infrastructure, equipment needed for green transition, pharmaceutical ingredients, and strategic and critical minerals, based on the suggestion of Hung Tran, “Our guide to friend-shoring: Sectors to watch”, Atlantic Council Issue Brief October 27, 2022.

[c] A separate effort at the United Nations Commission on International Trade Law focusing on reforming the procedural—versus substantive—aspects of investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS) provides an additional example of a facilitative approach.

[d] The process and outcome have been called ‘pro-multilateral’ by WTO Deputy Director-General Zhang Xiangchen when he was China’s ambassador and permanent representative to the WTO.

[1] “Transcript: US Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen on the next steps for Russia sanctions and ‘friend-shoring’ supply chains”, Atlantic Council, April 13, 2022.

[2] Deputy Prime Minister of Canada, Government of Canada, “Remarks by the Deputy Prime Minister at the Brookings Institution in Washington, D.C.”, October 11, 2022.

[3] International Monetary Fund, “World Economic Outlook: A Rocky Recovery”, Washington, DC., IMF, April, 2023, p. 110.

[4] “World Economic Outlook: A Rocky Recovery”, p. 111

[5] JaeBin Ahn, Ashique Habib, Davide Malacrino, and Andrea F. Presbitero. “Fragmenting Foreign Direct Investment Hits Emerging Economies Hardest”, IMF, April 5, 2023.

[6] “World Economic Outlook: A Rocky Recovery”, p. 96

[7] “Fragmenting Foreign Direct Investment Hits Emerging Economies Hardest”

[8] “World Economic Outlook: A Rocky Recovery”, p. 93

[9] “World Economic Outlook: A Rocky Recovery”, p. 104

[10] Shekhar Aiyar and Anna Ilyina, “Geo-economic fragmentation and the world economy”, VoxEU, March 27, 2023.; Shekhar Aiyar et al., “Geoeconomic Fragmentation and the Future of Multilateralism”, IMF Staff Discussion Note, January 15, 2023.; International Monetary Fund. “Regional Economic Outlook: Asia and Pacific”, IMF, October 2022.; Marijn A. Bolhuis, Jiaqian Chen, and Benjamin R Kett, “Fragmentation in Global Trade: Accounting for Commodities”, IMF Working Paper 2023/073, March 24, 2023.; Diego A. Cerdeiro et al., “Sizing Up the Effects of Technological Decoupling”, IMF Working Paper 2021/069, March 12, 2021.; Carlos Goes and Eddy Bekkers, “The Impact of Geopolitical Conflicts on Trade, Growth, and Innovation”, WTO Staff Working Paper ERSD-2022-09, July 4, 2022.

[11] Deepak Bagla, Ismail Ersahin, James X. Zhan, and Sean Doherty, “This new alliance is helping grow collaboration on international investment”, WeForum, May 24, 2022.

[12] Edward J. Balistreri and Zoryana Olekseyuk, “Economic Impacts of Investment Facilitation”, Working paper 21-WP 615, Center for Agricultural and Rural Development, Iowa State University, 2021.