Task Force 1: Macroeconomics, Trade, and Livelihoods: Policy Coherence and International Cooperation

The digital economy has revolutionised the world of work, and the care and domestic work sector is no exception. Less regulated than traditional labour markets, online platforms can offer new opportunities for care and domestic workers (CDWs). Yet, although some companies around the world have improved working standards, most platforms perpetuate poor conditions and erode labour rights. While the gig economy of care flourishes, opportunities emerge for a more just and inclusive world of on-demand work. Investing in the care economy, while tackling the challenges and seizing the opportunities of technology-enabled labour markets, should be a priority for the G20. This Policy Brief proposes a three-pillar strategy to advance the rights of CDWs in the gig economy: advancing comprehensive care systems, implementing social protection floors, and rethinking labour schemes for platform workers.

1. The Challenge

The digital economy has revolutionised the world of work, including the care and domestic work sector. There are 76 million domestic workers globally, of whom 76 percent are women and 17 percent are migrants.[1] In recent years, the share of CDWs in the gig economy has been rising[2] as technological developments lead to a proliferation of digital platforms, connecting care and domestic work providers with recipients.

Less regulated than traditional labour markets,[3] online platforms can offer new opportunities with lower entry costs for CDWs. In some cases, platforms may repackage opportunities already available in informal networks. Gig work is often presented as more flexible and autonomous than offline labour in terms of when, where, and how to work.[4] Yet, while some companies have improved the work standards for CDWs,[5] in most cases, platforms perpetuate poor conditions and erode labour rights.[6]

Lack of transparency is one of the primary challenges in the digitally enabled care and domestic work economy. A platform’s algorithm defines the working relationship’s conditions, such as job assignments or permanence on the platform, without disclosing the decision criteria. Workers are often unaware of the parameters that determine biases, rewards, and penalties.[7]

Box 1: Unpacking Care and Domestic Work

Additionally, the online economy replicates the precarious working conditions of CDWs offline. Workers often experience informality, insecure incomes and weakened protections.[8] Concerns also exist regarding safety and security, while opportunities for learning and professionalisation are limited.[9] Lack of protection is worsened due to the undefined labour scheme of platform workers.[10] Applying standard employment regulations and social protection schemes to platform jobs has offered few improvements.[11] In most countries, specific labour schemes for technology-mediated occupations are lacking and workers cannot access representation.

Even though the platform economy may offer flexibility, which can accommodate women’s needs, this view takes distribution of unpaid care and domestic work as a given while increasing the demand for ‘a casual, informal, on-demand workforce.’[12] The potential benefits of apps are often only an illusion as flexibility is determined by customer demand.[13] Women are more likely to be recruited through platforms as CDWs; this offers lower earnings, compared with the more lucrative location-based gig work.[14] The sector is particularly relevant for the employment of economically disadvantaged populations and migrants.

Additionally, the intimate and home-based nature of care and domestic work, along with the lack of protection offered by platforms, exposes women to higher risks of abuse.[15] Workers tolerate poor behaviour from clients or perform unexpected tasks out of fear of receiving low ratings or losing work.[16]

Box 2: Different Regions, Similar Challenges for CDWs in the Platform Economy

Despite the challenges, there are opportunities. Often, workers have leveraged their bargaining power to negotiate better conditions through private agreements with the platform.[17] While collective bargaining remains elusive, platform cooperatives, co-owned by workers, have shifted the focus from technology to people. Yet these enterprises are small-scale promises, compared with big tech companies.

Principio del formulario

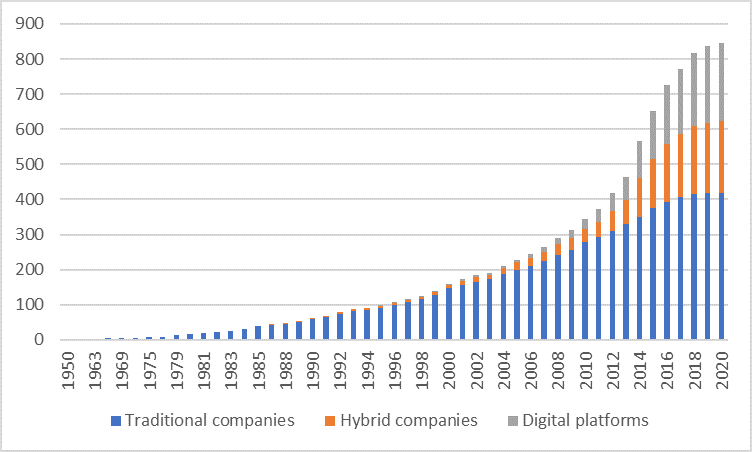

The care crisis is deepening worldwide, fuelled by ageing societies in the Global North, growing populations in the Global South, and insufficient policies to tackle families’ burden of unpaid care and domestic work. The heightened crisis of social reproduction and increased inequalities drive both demand and supply for care and domestic work. During the past decade, the number of platforms offering CDWs’ services has increased eightfold.[18]

Figure 1: Active Domestic Work Platforms, Global, 1950–2020

Source: ILO (2021), based on Crunchbase

While the gig economy of care flourishes, opportunities emerge for a more just and inclusive world of on-demand work. Online labour markets should not deepen the gender and structural inequalities existing offline in care and domestic work, where poor labour standards are the norm. Better policies and regulations in the digitally enabled care and domestic work economy can create new opportunities with improved working conditions, reduce the share of unpaid work carried out by women and girls, and increase access to quality care, enhancing well-being and economic development of society.

2. The G20’s Role

The G20 has made progress in prioritising the care agenda. In 2014, leaders committed to reducing the gender gap in labour participation by 25 percent by 2025.[19] The G20 Roadmap Towards and Beyond the Brisbane Target, introduced in 2021, also highlighted the role of care policies in creating job opportunities for women.[20]

Parallel to these efforts, Italy’s G20 presidency introduced the G20 Policy Options to Enhance Regulatory Frameworks for Remote Working Arrangements and Work through Digital Platforms, building on previous agreements reached in Saudi Arabia (2020), Argentina (2018), and Germany (2017). These commitments, along with India’s prioritisation of the topic, create an opportunity to advance the rights of workers in the digitally enabled economy.

The G20 represents a unique platform to address the care crisis, build a fair gig economy, and improve livelihoods. By incentivising decent work, advancing data collection and research, fostering alliances, and rethinking labour schemes, the G20 countries can deliver on gender equality and workers’ well-being.

Three points summarise the potential of the G20 to deliver on these aspects:

- Global leadership: Being home to two-thirds of the global population and given its role as a donor, the G20 can impact virtually every individual in the world. The G20 countries can lead by example, setting targets and policies to inspire interventions worldwide. Furthermore, the G20 has the economic power to coordinate investments in the care economy and anticipate technology’s challenges. Through cross-country cooperation, these investments can create decent jobs in care and domestic work, developing positive innovations through digital platforms.

- Convening role: Digitally mediated care and domestic labour represents the changing nature of work in a digitised and global world, requiring new frameworks and policy approaches across borders. Care and domestic work platforms are often run by multinational firms, with far-reaching implications for international finance, taxation, and laws. The G20 can foster multilateral discussions and encourage global agreements, gathering stakeholders to explore ways to profit from the possibilities that digital labour markets bring while guaranteeing CDWs’ rights.

- Peer learning: Limited data on CDWs, especially those employed through digital platforms, create barriers to implementing evidence-informed policies.[21] The G20 offers positive prospects to implement peer-learning mechanisms that inform country decisions. Governments and other stakeholders can gather in ministerial meetings and engagement groups, and through the Development Working Group to discuss solutions to common problems, sharing knowledge and best practices.

3. Recommendations to the G20

Investing in the care economy while tackling the challenges and seizing the opportunities that technology-enabled labour markets bring, should be a priority for the G20. Maintaining the status quo can result in digital platforms exacerbating deficits in decent work and dignified livelihoods that CDWs currently experience.

This Policy Brief proposes a three-pillar strategy to advance gig workers’ rights in the care and domestic work sector, mitigating risks and maximising the positive impact of the digital transformation of labour markets, while adopting a care economy lens in the G20 and beyond.

Proposal 1: Advancing comprehensive care systems

In most countries, care policies have proved to be insufficient for supporting families’ care needs and ensuring workers’ decent labour conditions. Comprehensive care schemes can yield multiple benefits, including supporting the development of capabilities of the new generations, promoting gender equality, and ensuring human rights. Investing in the care economy can also lead to economic returns through job creation and GDP growth.[22]

To accomplish this, care policies should shift from siloed interventions to articulated and coherent policy systems that recognise care’s value, reduce the burden of unpaid care, and redistribute it among genders and across society.[23] This policy approach should also enable collective representation for care workers and reward them fairly. This 5R Framework promotes rights-based, gender-sensitive and transformative impact on society through reducing gender and socioeconomic inequalities and guaranteeing quality care.[24]

The G20 countries should implement systemic care policies, in line with the commitments established on the G20 Roadmap Towards and Beyond the Brisbane Target, and foster cooperation mechanisms to facilitate their implementation in other economies. This policy scheme should contemplate the following interventions.

Recognising, reducing, and redistributing unpaid work involve:

- developing standard methodologies to measure the economic contribution of unpaid work and estimate a basic care basket;

- investing in quality care infrastructure for children, the elderly and people with disabilities, and prioritising care investments through donor schemes in the Global South; and

- enacting policies that promote work-family balance and shared responsibility within households, including gender-sensitive parental leaves.

Rewarding and representing CDWs involve:

- ratifying the International Labour Organization’s Domestic Workers Convention and enacting labour schemes that ensure CDWs’ labour rights and protection; to date, only 36 countries, mostly in the Global South, have ratified the convention;

- guaranteeing freedom of association and offering support in countries where participation is limited due to restricted unionisation or civil society operations; this action should include cooperation between unions among migrant CDWs’ countries of origin and destination;

- fostering social dialogue among care workers, unpaid caregivers, care recipients, and businesses; and

- providing training opportunities to CDWs, particularly for those in the informal economy; these opportunities should consider skills portability and recognition for migrant CDWs and seek to attract more men to the sector. Principio del formulario

Box 3: Innovative Solutions for Migrant CDWs

Proposal 2: Implementing social protection floors

The fast-paced changes in the world of work, driven by technology and demographic shifts, demand rethinking of social protection schemes. New non-standard employment relationships, such as those created by the platform economy, pose challenges to providing full coverage to all workers, especially to CDWs. Effective and sustainable social protection for all workers can promote their well-being and mitigate the negative effects of a ‘race to the bottom’ in the platform economy while fostering productivity.

Many countries have made progress on extending social protection to workers in the digitally enabled economy, including to CDWs, through contributory and non-contributory mechanisms. This progress is in line with the G20’s intentions established in the last three Leaders’ Declarations to expand social protection and protect platform workers.

The following proposals can contribute to building social protection systems that are inclusive, sustainable, and adequate for all, including for platform CDWs:

- ensuring access to social protection entitlements and their portability, regardless of changes in employment status, sector, country of residence or the combination of dependent and independent work;

- establishing universal social protection floors, based on national contexts, guaranteeing access to essential healthcare services and basic income security as a minimum; and

- the G20 exploring social protection alternatives that combine contributory (social security-based) and non-contributory (tax-financed) entitlements, which can include taxation of platform corporations, to ensure ample coverage, fiscal viability, and sustainability.

Proposal 3: Rethinking labour schemes for gig workers

Countries must re-examine their legal frameworks to protect platform workers’ rights. Understanding and defining employment relationships in the digitally enabled economy is essential to achieve this goal. The employment status of platform workers determines the type of social protection they can access and their labour rights.[25] Currently, ‘misclassification’ leads to relationships between employees and employers, often being disguised as independent work.

In 2020, the G20 Labour and Employment Ministerial Declaration committed to ensuring universal social protection, regardless of employment status, underscoring the importance of identifying the nature of employment relationships. The Declaration outlined several commitments that require further action from the G20 countries:

- facilitating information on existing regulations to correctly classify employment relationships and workers’ and employers’ rights and responsibilities;

- reducing incentives to disguise employment relationships as self-employment while providing alternatives for workers, who choose self-employment;

- implementing easy procedures for challenging decisions on employment status and ensuring that authorities take rapid and fair decisions on the matter;

- making public services available that facilitate social insurance registration; and

- promoting labour inspections and interventions to monitor and detect breaches while ensuring social protection for everyone, regardless of location or employment status.

Furthermore, the G20 provides a unique platform for convening tripartite meetings to rethink labour regimes and how they reflect the reality of platform workers. These discussions should consider labour rights, algorithms, data governance, and multiple employment relationships. Unions and workers’ collectives should have a space to advocate and negotiate for workers’ rights in these forums.

For the digitally enabled care economy, these conversations can consider the opportunities for promoting care delivery models through innovation and employer-supported care.

4. Conclusion

The rise of digital platforms has created both new opportunities and challenges in the care and domestic work economy. While platforms may offer flexible work arrangements and access to job opportunities, they can also perpetuate poor working conditions and exacerbate inequalities. To ensure their positive impact, the G20 countries need to act through coherent regulations and effective policies that prioritise the well-being of caregivers and care recipients.

While governments must play a leading role, a whole-of-society approach is needed to move forward. This framework should acknowledge the contribution of all stakeholders and promote coordination as multisectoral actions can incorporate diverse perspectives and better respond to social needs. Mainstreaming gender and a human rights approach across the design of these policies is also vital to ensure that women, who represent the largest share of CDWs, are appropriately benefitted.

Crucially, to enhance these policy proposals, the G20 should gather gender-sensitive, quality data to inform decision-making. This information can contribute to diagnosing the situation, evaluating impact, and monitoring progress. It can also help understand workers’ experiences and the functioning of algorithms.

To this end, governments and platforms should engage in data-sharing agreements, particularly with regard to the care economy, wherein women’s work has long been invisible. The G20 can also partner with international organisations to collect data and expand collaboration with G20 engagement groups to produce evidence, supporting the Global South in this endeavour.

Through these approaches, the G20 can foster a more equitable and sustainable care and domestic work economy for all, which profits from the opportunities enabled by technology.

Attribution: Florencia Caro Sachetti, “Mitigating Risks and Harnessing Opportunities for the Digitally Enabled Care Economy,” T20 Policy Brief, June 2023.

Endnotes

[1] ILO, ‘Making Decent Work a Reality for Domestic Workers. Progress and Prospects Ten Years after the Adoption of the Domestic Workers Convention, 2011 (No. 189)’, 2021.

[2] Abigail Hunt and Fortunate Machingura, ‘The Rise of On-Demand Domestic Work’, Working paper, Development Progress (London: ODI, 2016).

[3] Anna Ilsøe, Trine P. Larsen, and Emma S. Bach, ‘Multiple Jobholding in the Digital Platform Economy: Signs of Segmentation’, Transfer: European Review of Labour and Research 27, no. 2 (1 May 2021): 201–18.

[4] Sabina Dewan, ‘Women, Work, and Digital Platforms: Enabling Better Outcomes for Women in the Digital Age’ (UN Women, 2022).

[5] Olivia Blanchard, ‘Las plataformas digitales de cuidados y sus servicios workertech en América Latina y el Caribe’ (Banco Interamericano de Desarrollo, 7 February 2023).

[6] Julia Ticona and Alexandra Mateescu, ‘Trusted Strangers: Carework Platforms’ Cultural Entrepreneurship in the on-Demand Economy’, New Media & Society 20, no. 11 (1 November 2018): 4384–4404.

[7] Niels van Doorn, Stepping Stone or Dead End? The Ambiguities of Platform-Mediated Domestic Work under Conditions of Austerity. Comparative Landscapes of Austerity and the Gig Economy: New York and Berlin, Working in the Context of Austerity (Bristol University Press, 2020).

[8] Hunt and Machingura, ‘The Rise of On-Demand Domestic Work’.

[9] Abigail Hunt et al., ‘Women in the Gig Economy. Paid Work, Care and Flexibility in Kenya and South Africa’ (ODI, 2019).

[10] Valerio De Stefano, ‘The Rise of the “Just-in-Time Workforce”: On-Demand Work, Crowdwork, and Labour Protection in the “Gig-Economy”’ 37 (2016): 35; Hunt et al., ‘Women in the Gig Economy. Paid Work, Care and Flexibility in Kenya and South Africa’.

[11] Paul Schoukens, Eleni De Becker, and Alberto Barrio Fernandez, ‘Platform Economy and the Risk of In-Work Poverty: A Research Agenda for Social Security Lawyers’, in A Research Agenda for the Gig Economy and Society, ed. Valerio De Stefano et al. (Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing Ltd., 2022), 93–112.

[12] Bama Athreya, ‘Bias in, Bias out : Gender and Work in the Platform Economy’, Working Paper (IDRC, 21 May 2021).

[13] Hunt et al., ‘Women in the Gig Economy. Paid Work, Care and Flexibility in Kenya and South Africa’.

[14] Shamira Ahmed et al., ‘Future of Work in the Global South (FOWIGS): Digital Labour, New Opportunities and Challenges (Working Paper)’ (Research ICT Africa, 2021).

[15] Athreya, ‘Bias in, Bias Out’.

[16] Alexandra Mateescu and Aiha Nguyen, ‘Algorithmic Management in the Workplace’ (Data & Society, 2019).

[17] Erica Smiley, ‘Domestic Workers Are Using the Gig Economy Against Itself’, 25 June 2021.

[18] ILO, ‘Making Decent Work a Reality for Domestic Workers. Progress and Prospects Ten Years after the Adoption of the Domestic Workers Convention, 2011 (No. 189)’.

[19] G20, ‘G20 Leaders’ Communiqué’ (Brisbane Summit: G20, 2014).

[20] G20, ‘G20 Roadmap Towards and Beyond the Brisbane Target: More, Better and Equally Paid Jobs for Women’ (Italy: G20, 2021).

[21] Florencia Caro Sachetti et al., ‘Women in Global Care Chains: The Need to Tackle Intersecting Inequalities in G20 Countries’, Global Solutions Initiative | Global Solutions Summit (blog), 2020.

[22] Jerome de Henau, Costs and Benefits of Investing in Transformative Care Policy Packages : A Macrosimulation Study in 82 Countries, vol. 55, ILO Working Paper (International Labour Office, 2022).; Gala Díaz Langou et al., ‘Empleo, crecimiento y equidad. Impactos económicos de tres políticas que reducen las brechas de género’, CIPPEC, 2019.

[23] Florencia Caro Sachetti et al., ‘Migrant Care and Domestic Workers during the Pandemic and beyond: The G20’s Role in Tackling Inequalities and Guaranteeing Rights’, T20, 2022.

[24] ILO, Care Work and Care Jobs for the Future of Decent Work (Geneva: International Labour Organization, 2018).

[25] ILO, ISSA, and OECD, ‘Providing Adequate and Sustainable Social Protection for Workers in the Gig and Platform Economy. Technical Paper Prepared for the 1st Meeting of the Employment Working Group under the Indian Presidency’, 2023.