It is now a trope of economic discourse that before Adam Smith became widely known for his “invisible hand” theories, he had long been a moral philosopher at the University of Glasgow, chiefly concerned about the impulse of virtue in the actions of human agents.

There is, thus, some appreciation that the worlds of finance and economics are not congenitally coded to the “greed is good” logic in the minds of its principal shapers. The rise of Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) themes as the organising philosophy for restoring ethics and social trust into the architecture of global finance has, therefore, encountered little analytical friction. Those who object do so mostly on political-ideological grounds. And, at any rate, the tide seems to be against them.

The European Union’s Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR) represents, in this vein, a high watermark in the journey of ESG in the financial sector so far. As we have witnessed with General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), what Europe promotes inevitably becomes “global” in matters of regulatory best practice.

For the asset and funds management industries, the prospect of clear regulation aiming to reconfigure the capital allocation process in favour of the socially desirable amounts to a bar of ethics way beyond traditional compliance.

It is a trite fact that the allocative function of the asset and fund management companies (“funds”) of the world is the principal shaper and driver of the entire global financial architecture. Analysts have argued that the embrace of SFDR in its most expansive sense is inevitable because the value of “virtue premium” today far supersedes the “brand premium” logic of yesterday, and, is thus, somewhat more resistant to greenwashing. That is to say, there is a shift to “virtue ethics” beyond mere consequentialism (i.e. fear of regulatory enforcement).

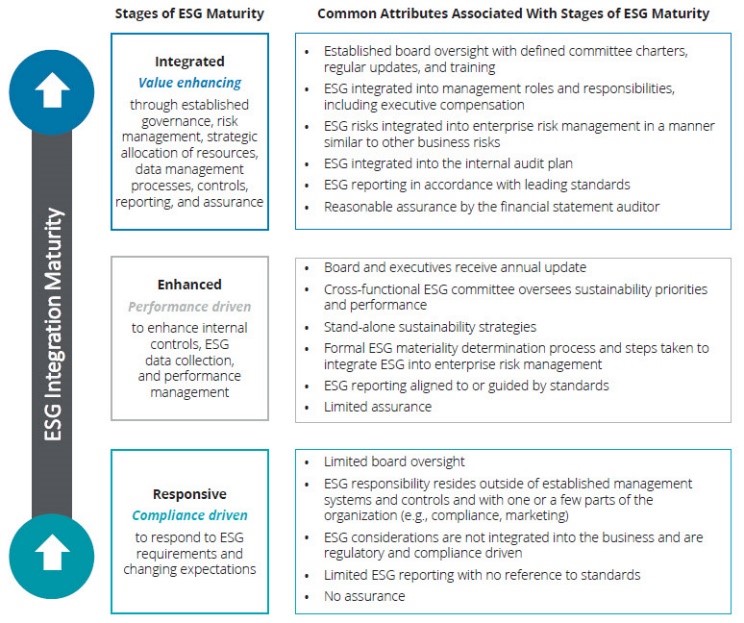

Funds, we are told, crave the clear “virtue signal amplitude” required to sustain the virtue premium that is conferred by the enhanced ESG compliance derived from “opting up” for SFDR Articles 8 and 9 status. In this framing, funds have been said to have a strong willingness to invest in enhanced compliance beyond the bare regulatory demands (or to attain what Deloitte calls “value enhancing” ESG alignment) provided the signal amplitude is high enough (appendix 1).

Lenhard offers three main reasons for why venture capital (VC) funds, for instance, might be keen to opt for “enhanced compliance”. The first is that enhanced ESG compliance can “add value” to the actual process of building and running a successful fund or financial entity. The second is that those who inject money into VC funds (the so-called “limited partners”) are demanding more substantive compliance. In fact, some major sources of capital in Europe such as development finance institutions (DFIs)—the likes of KfW Development Bank and the European Investment Bank, among others—make it a minimal bar for investment. And the third focuses on the need to stay ahead of the regulatory curve, presumably for risk management reasons.

Together, these material factors determine the “virtue signal amplitude” of ESG action. Virtue amplitude is, thus, self-evidently even more vital for ESG to be effective in serving as any form of differentiator in the marketplace and social arena than is the case for “more material” business metrics, such as the various financial accounting ratios.

For any of these three reasons to embed natively in financial institutions, however, the fraught issue of sound accounting must be confronted.

ESG accounting has a number of features that militate against some of the momentum behind virtue-based compliance (or the nativist approach) whilst incentivising “checkboxing”.

Despite the emergence last year of the International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB), there is still a considerable gap between the mere popularity, or even global legitimacy, of reporting frameworks and the regulatory clarity about what to do when reported ESG measures vary.

To the extent that no major market regulator has been able to endorse an overarching framework, direct comparability of ESG scores across different operational categories and companies is not possible today with any degree of confidence.

The decision by the capital markets regulator (SEC) of the United States to go after Goldman Sachs for apparent ESG misreporting creates the erroneous impression that standardisation is at a point where clear regulatory enforcement against material misstatements is now routine as in the case of traditional financial accounting.

In actual fact, the SEC action was predicated on factual mismatches between Goldman’s marketing materials and the operations of the funds in question, and not the ESG measures, indicators or any fundamental disclosure integrity elements.

As in the BNY Mellon enforcement action, the concern was about whether ESG was in fact a criterion for investment across a substantive enough proportion of the fund to allow blanket ESG branding in the way Goldman had done. The concern was thus less about the integrity of the ESG accounting done at the firms, and more for the seemingly fraudulent marketing. So, fundamentally consequentialist.

The lack of standardised, easily comparable, metrics furthermore makes it hard for companies today to effectively use ESG to bolster their competitive edge and reduces the attractiveness of going beyond checkboxing. It does not encourage greenwashing so much as it does green-hustling. The following factors are key in understanding how to improve the situation.

- To the extent that in traditional investing, prevailing metrics play up the importance of one-dimensional comparability, ESG accounting’s growing complexity reduces the attractiveness of using ESG metrics for signalling authenticity.

- Unlike in traditional financial accounting, the ESG accounting load does not necessarily scale down in line with an enterprise’s reducing scope and size. ESG accounting is subject-specific. A small enterprise operating in a particular geography, industry, or supply chain can see dramatic increases in their reporting burden without a corresponding growth in revenues or operational scope.

- McKinsey estimates that only 2 percent of enterprises have visibility beyond the second tier of their supply chain. In the financial technology space, for instance, tiers can multiply at whim. Data-centre emissions, API-entanglements with nefarious cyber players, hardware component origins, product addiction levels, and a host of the emerging ESG issues in fintech investing are literally unfathomable regardless of size and operational scope.

All this heavy complexity and interdependency interfere with the capital allocation decision-maker’s preference for simple, sharp-edged, metrics for competitive advantage and encourages minimal compliance and green-hustling instead of “opting up” and “nativist compliance”.

What is required, therefore, is not more elaborate ESG schemas, but a far more pragmatic framework addressing the above-stated requirements:

- Enterprise-fitting

- Data-driven due diligence

- Ratings baselining

Until these much more concrete developments take place, instruments like the SFDR amount to little more than, in the words of Zetzsche & Anker-Sorenson, “regulating in the dark” and the path to nativist compliance will remain murky.

Appendix 1

Source: Deloitte (2020)