Task Force 2: Our Common Digital Future: Affordable, Accessible, and Inclusive Digital Public Infrastructure

Abstract

As the COVID-19 pandemic threatened to push millions of people globally into extreme poverty, many countries worldwide, including the G20 countries, heightened their efforts to expand cash transfer and economic empowerment programs to cushion the impact of the pandemic. The surge in demand for both these programs put a tremendous strain on the pre-existing social protection programs. This Policy Brief highlights the lessons learned from Indonesia’s Kartu Prakerja Program as a case of leveraging digital public infrastructure (DPI) as a ‘technofix’ to deliver nationwide conditional cash transfers (CCT) for training provision. The authors propose a new use for DPI in G20 countries through API integration for various systems to support cash transfers, including verification with biometrics and KYC, data exchange, and payment disbursement. DPI can ensure CCTs are delivered fast, on a large scale, and to the right people, in an inclusive and secure manner.

1. The Challenge

The adverse impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic demanded a robust social protection system for all. In particular, social protection mechanisms were required to be more flexible and reach more people. This situation highlighted challenges in Indonesia’s social assistance system, particularly regarding social aid and beneficiary targeting. Additionally, the pandemic has also resulted in loss of job opportunities and a reduction in human capital accumulation. Thus, the provision of training for skilling, reskilling, and upskilling is necessary to address the issue.

In response to the shock of Covid-19, The Government of Indonesia (GoI) introduced the Kartu Prakerja Program in 2020 as a large-scale skill development program to improve workforce competence, productivity, competitiveness, and entrepreneurial skills. The program got an additional mandate from the government to act as a social assistance initiative in the form of a conditional cash transfer (CCT) program for training provision. As a CCT program, the Kartu Prakerja required beneficiaries to complete their first training before receiving post-training cash incentives. The program used an end-to-end digital mechanism and maximised the role of DPI technology to create an ecosystem with multiple stakeholders and provide nationwide benefits. As of 2022, Kartu Prakerja has reached 16.4 million beneficiaries with less than 200 operational personnel.

Challenges to Social Assistance Mechanism

a. The targeting of social assistance program beneficiaries

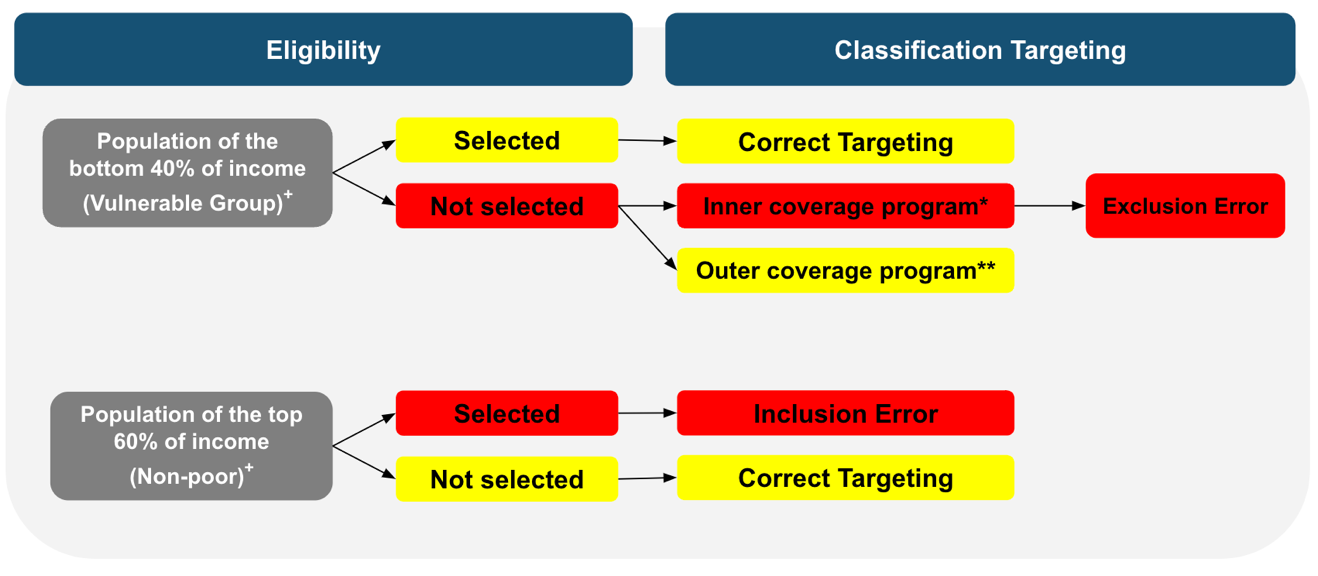

Beneficiary targeting for social assistance programs is crucial because it determines who is eligible to receive social assistance. During implementation, common issues such as exclusion and inclusion errors can lead to targeting inaccuracies. Exclusion errors occur when individuals or households eligible for social assistance do not receive the intended support due to bureaucratic inefficiencies or lack of access to essential information and services. Conversely, inclusion errors occur when those who are not eligible receive support. Figure 1 illustrates how these two types of errors occur.

Figure 1. Classification of Targeting Errors[1]

Notes: ⁺The decision on social assistance eligibility criteria and the threshold of correct targeting is based on the Indonesian Unified Database (UDB/Basis Data Terpadu).

*Inner coverage program refers to the group of people who are eligible and included within the program coverage but do not receive the program due to an error. This is considered an exclusion error.

**Outer coverage program refers to the group of people who are eligible but do not receive the program because they are not included in the program coverage. This is due to budget constraints and is not considered as an error.

Exclusion and inclusion errors in social assistance distribution remain a persistent challenge in many countries. These errors impede the effectiveness of programs in reaching the most vulnerable populations who need them most. For instance, during the pandemic, inaccuracies in data-gathering in West Java, Indonesia, led some village officials to refuse social assistance as it was deemed mistargeted. As a result, the assistance reached only some intended recipients and a misallocation occurred.[2]

b. The disbursement mechanism

Despite the implementation of an account-based social assistance payment through a state-owned bank (prior to COVID-19), Indonesia still faced challenges in disbursements during the pandemic. These included dependency on helpers for the cash-out process, underdeveloped telecommunication infrastructure, and a lack of financial access points and ATMs, which led to high transportation costs.[3] The varying development levels and uneven geographical conditions across regions exacerbated this problem.

Transparency in social assistance distribution also posed a significant issue. A rapid survey regarding the implementation of social assistance in Indonesia found that 55 percent of respondents believed there was a lack of transparency in social assistance delivery during the COVID-19 pandemic.[4] The system was ineffective in certain regions due to the potential misappropriation of funds and illegal levy practices.

The challenges of providing and delivering social assistance efficiently and effectively are not unique to Indonesia. Problems of mistargeting and unaccountable assistance delivery prior to and post the COVID-19 are also prevalent in other G20 countries, such as Argentina,[5] India,[6] Italy,[7] and Mexico.[8]

Challenges in Training Provision

Indonesia faces the challenge of high unemployment every year and closing the skill gap is a critical area that the government needs to address. A well-implemented vocational education and training (VET) system providing training relevant to the labour market can reduce unemployment, particularly among the youth.

A large majority (90 percent) of Indonesia’s workforce has never received any training.[9] For many, especially those living in remote or rural areas where access to training was laborious, traditional training was difficult to access due to their limited time and the unaffordability of training costs.[10] Another challenge was the lack of information about relevant training opportunities. Workforce need information about potential future skills needed to make decisions on which training to take to avoid mismatch between the skills acquired and the labour market demands.[11]

Lastly, financial constraints pose a significant barrier for many Indonesians. The cost of enrolling in training programs was often prohibitive, particularly for low-income individuals who needed skill development the most. Additionally, there was limited financial assistance available to support individuals to access and complete the training programs.

The training provision challenges in Indonesia are also apparent in other G20 countries. Other findings showed that skill mismatch is significant in G20 countries, with over 30 percent of people being over- or under-qualified for their job.[12] This problem of skill mismatch in G20’s advanced and emerging economies calls for further skill development.

2. The G20’s Role

Viable Opportunities for G20 Countries: DPI Utilisation

DPI is an open-source identity platform that enables access to a wide range of private and government services through the building of applications and products. The six key principles of DPI are: (1) unbundling foundational elements; (2) identifying and implementing a series of 1+ steps (or one thing that triggers another thing rapidly); (3) thinking about the ecosystem; (4) building only interoperable; (5) designing to unify; and (6) catalysing inclusive by design innovation. These six principles enable open and non-linear innovation in the ecosystem and encourage the distribution of the ability to solve problems.

Inclusive infrastructure enables inclusive innovation. By prioritising inclusion, DPI can empower people, reduce the digital divide, catalyse innovation for scale and serve all. Another study also found that countries that could leverage investments in digital public infrastructure, such as ID, payments, and data sharing, were able to implement COVID-19 response programs better and reach more beneficiaries.[13]

Many G20 countries are well aware of the importance of DPI development, though their reasons for developing DPI might vary. First, governments may aim for good governance by realising e-governance or protecting people’s data security. This is reflected in the efforts by the governments of France, Italy, and Japan, which have started creating a secure cloud environment for government agencies. Second, governments are encouraging that public services be simplified. In India, there is a digital identity called Aadhar, real-time fast payment and a platform to safely share personal data without compromising privacy.

G20 Efforts and Commitments

The G20 plays a significant role in promoting the use of digital technology to improve public services and social protection programs. G20 Saudi Arabia[14] stated that countries need to promote responsible digital payments and new technologies to support a strong, inclusive and sustainable recovery. G20 Italy[15] expressed the commitment to strengthening institutional capacities to deliver timely and effective public services to eligible people by investing in inclusive digital technologies. Commitments to Adaptive Social Protection (ASP) are also stated in the G20 Indonesia,[16] specifically stating the aim to promote policy dialogue to build and enhance the use of digital technologies for deploying ASP benefits. In 2023, G20’s discussion on this matter is further explored in the framework of DPI, providing a viable opportunity for countries to tackle their conditional cash transfer challenges.

3. Recommendations to the G20

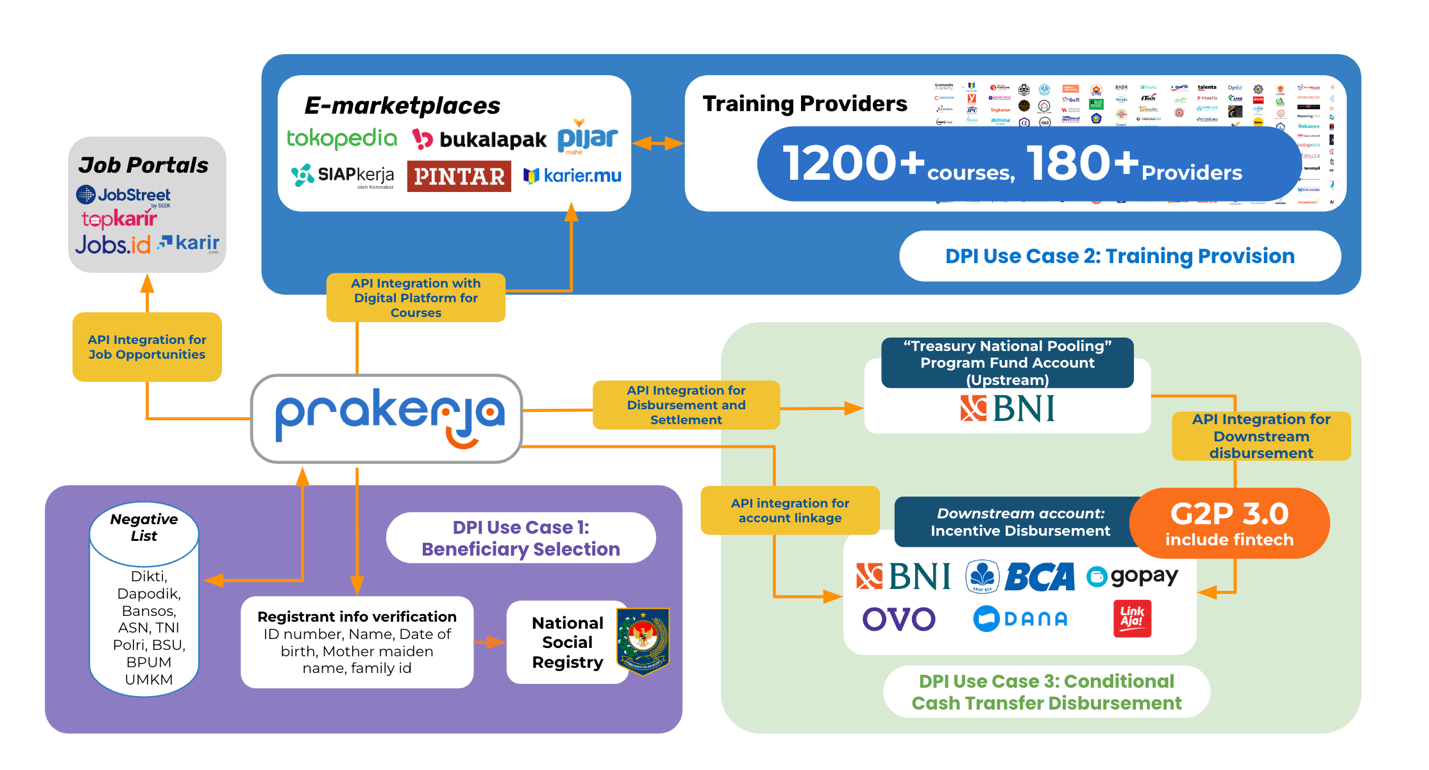

Using the case of the Kartu Prakerja program in Indonesia, this Policy Brief offers a plausible solution: to leverage DPI and use its tools in the form of Application Programming Interface (API) for registration, selection of the beneficiaries, and cash disbursement. Prakerja API is a well-structured RESTful Web Service that serves as a communication bridge between Kartu Prakerja partner (Digital Platform, Training Provider, and Payment Partner) and Prakerja system.

Figure 2. Kartu Prakerja Ecosystem

Source: PMO of Kartu Prakerja

Due to Kartu Prakerja’s unique blend of skill development and social assistance programming, its case offers specific examples of DPI utilisation in three different areas: (1) DPI use for beneficiary selection; (2) DPI use for training provision; and (3) DPI use for conditional cash transfer disbursement (see Figure 2).

DPI Use Case for Beneficiary Selection

i. Data Verification

The design of the Kartu Prakerja program is based on an on-demand application model. Individuals must register themselves digitally, which requires data verification. API Integration is beneficial for connecting the Kartu Prakerja registration platform with the Population and Civil Registration Agency to verify the national IDs of those who register.

This program leverages digital infrastructure tools in the form of biometric analysis, including face recognition and liveness-checking technology. Liveness checking enables the detection of real-time biometric data, such as facial data from a live user. Face recognition then allows the confirmation of a person’s identity directly. With this system, Prakerja can measure the uniqueness of registrants, and it provides additional verification by matching the information to the national ID.

ii. Eligibility Checking

API Integration allows Prakerja to exchange data with other ministries or government agencies and strengthen eligibility checking. By integrating Prakerja registration into the Ministry of Social Affairs database, this program ensures that the beneficiaries are not receiving double social protection programs. Enhancing the functionality of data sharing between government agencies minimises the social program targeting error.

DPI Use Case for Training Provision

As mentioned earlier, Kartu Prakerja is a conditional cash transfer program with training as the conditionality. After being identified as Kartu Prakerja beneficiaries, people can purchase and participate in training. In its implementation, Kartu Prakerja leverages DPI in at least two aspects of its training:

i. Creating an Integrated Training Ecosystem

In providing trainings, Kartu Prakerja utilises API integration with six e-marketplaces as the platform for beneficiaries to purchase training. The training institutions join the ecosystem by registering through integrated e-marketplaces and passing Kartu Prakerja’s assessment process. Each training institution can then submit as many training courses as they need, as long as they pass Kartu Prakerja’s robust assessment process.

This integrated system creates a compounding effect, in line with DPI’s key principle, which is to identify and implement as a series of 1+ steps. With the integration of six e-marketplaces, Kartu Prakerja has been able to connect beneficiaries with more than 188 training institutions that provide more than 1,200 training courses in less than two years. Based on the evaluation surveys, more than 92 percent of beneficiaries state that all partners of Kartu Prakerja are of good quality.

ii. Fostering Customer-centric Design

The issue of skill mismatch in the labour market cannot be resolved with a single type of training and therefore it is crucial to provide choices to customers. However, it is also important to avoid scattering information. Kartu Prakerja solves this problem by designing a unified selection of training courses from all training providers in its ecosystem. While accessing training options can be done in the Kartu Prakerja platform, the learning process—such as accessing the Learning Management System (LMS) or attending the online webinar—are done in each e-marketplace or on the training providers’ own platform. The beneficiaries still have the option to decide which training courses and modes are most appropriate for their needs. This implementation aligns with DPI’s key principle of ‘design to unify, not make everything uniform’.

This unification also reflects how partnerships between public and private sectors can result in a wider variety of training courses for beneficiaries. A survey from Cyrus Network in 2021[17] found that 98 percent of beneficiaries stated that Kartu Prakerja training course options are varied. On average, training courses in Kartu Prakerja received a 4.9/5 rating from the trainees. Results from the World Bank and TNP2K survey[18] show that 96,1 percent of beneficiaries were satisfied with their first training.

DPI Use Case for Conditional Cash Transfer (G2P Payment)

Upon completion of their training, Kartu Prakerja beneficiaries are eligible to receive a cash transfer. Each beneficiary can receive up to 600,000 Rupiah (US$40) per month for four months. They will also receive incentives for completing evaluation surveys, with three surveys offering incentives of 50,000 Rupiahs (US$3.40) per survey. This conditionality status is stored and updated through their 16-digit Prakerja ID number, which acts as a unique ID connecting training data from e-marketplaces and cash transfers data from payment partners.

Prakerja has implemented an integrated system with digital and cloud technology for extensive public service in the form of incentive disbursement, namely, Government-to-person (G2P) Payment 3.0. This is the first successful application of G2P Payment 3.0 in Indonesia.[19] Using the G2P payment concept, Prakerja can transfer the cash incentive directly to the beneficiaries’ virtual accounts. This fulfils the DPI principle of thinking about the ecosystem.

i. Interoperable Disbursement Mechanism

Prakerja has six payment partners in the ecosystem, including four e-wallet providers and two banks integrated via API. Prakerja provides incentive distribution channel options to beneficiaries in order to serve people, including those in the last mile. This kind of distribution mechanism changes the mode of distribution from traditional to digital. Collaborating with digital payment partners allows beneficiaries to open accounts very simply and access them only through a mobile phone, with a fee structure that is affordable and justifiable relative to the cost of manual distribution. This is confirmed by the World Bank survey[20] that stated about 96 percent of beneficiaries are satisfied with cashless incentive disbursement.

Additionally, the integration between Prakerja and payment partners via API can also prevent corruption because the beneficiaries’ accounts must have gone through the electronic Know Your Customer (e-KYC) process. This is an attempt to prevent fraud by verifying personal and account information prior to making financial transactions. Furthermore, the government incentives are fully channelled to the beneficiaries without fee deductions. Prakerja also monitors and ensures that the payment partners carry out their duties and functions.

Specific Recommendations for G20 Countries

- The G20 can facilitate the exchange of best practices and lessons from the implementation of DPI-enabled conditional cash transfer programs, such as the Kartu Prakerja model. By organising forums, workshops, and conferences, the G20 can bring together policymakers, experts, and practitioners to discuss their experiences in leveraging DPI for social assistance delivery.

- The G20 can play a crucial role in providing capacity-building and technical assistance to countries seeking to adopt or enhance DPI in their social assistance programs. The G20 can help countries establish DPI-enabled conditional cash transfer programs by providing support. This support can range from sharing expertise in digital ID systems, API integrations, and data analytics to guiding regulatory frameworks, privacy concerns, and cybersecurity measures.

- The G20 can promote research and innovation in the field of DPI for social assistance by supporting academic institutions, think tanks, and the private sector. This can contribute to a better understanding of the potential benefits and challenges of leveraging DPI in conditional cash transfer programs and inform the design of more effective and efficient initiatives.

- The G20 can advocate for the development of a global DPI framework in social assistance programs. By establishing common standards, principles, and guidelines, this framework can ensure the interoperability, security, and sustainability of DPI-enabled initiatives across countries. This can facilitate cross-border cooperation and data exchange, thus improving social assistance programs and inclusive growth worldwide.

In conclusion, this Policy Brief has underscored the tremendous potential of DPI in transforming social assistance delivery, enhancing efficiency, transparency, and inclusivity. Indonesia’s Kartu Prakerja program exemplifies the power of leveraging digital tools and systems to drive substantial improvements in the implementation of nationwide conditional cash transfer initiatives. By adopting innovative approaches like Kartu Prakerja, governments can better target and support vulnerable populations, ensuring the right beneficiaries receive prompt and secure assistance.

Attribution: Suhono Suharso Supangkat et al., “Leveraging Digital Public Infrastructure to Deliver Nationwide Conditional Cash Transfers for Training Provision,” T20 Policy Brief, June 2023.

Endnotes

[1] Annissa S. Kusumawati, “The Effectiveness of Targeting Social Transfer Programs in Indonesia.” The Indonesian Journal of Development Planning III, no.3 (December 2019), 285-286.

[2] Jimmy Daniel Berlianto Oley, “Urgency of Improving Indonesia’s Social Assistance System amid the COVID-19 Pandemic”, The SMERU Research Institute, 2020.

[3] National Team for the Acceleration of Poverty Reduction (TNP2K), Indonesia Fintech Association (AFTECH), and Lembaga Demografi Faculty of Economics and Business Universitas Indonesia (LDFEBUI). “Modernisasi Government to Person (G2P) Melalui Solusi Financial Technology (Fintech) di Indonesia”, 2020.

[4] Ministry of Social Affairs. “Pastikan Masyarakat di Kawasan 3T Terjangkau Bansos, Mensos Risma Siapkan Aturan Khusus.” Press Release of Minister of Social Affairs, 2021.

[5] OECD, “Digital Government Review of Argentina Accelerating the Digitalisation of the Public Sector”, 2018.

[6] Shagun, “Cash, on delivery: How India has taken up DBT in the times of COVID-19”, 2020.

[7] ISSA, “Social Security Responses to COVID-19: the Case of Italy”, 2020.

[8] Stephen Kidd, “The Demise of Mexico’s Prospera Programme : A Tragedy Foretold”, 2019.

[9] Denni Puspa Purbasari, Elan Satriawan, and Romora E. Sitorus. “Kartu Prakerja: A Breakthrough for Boosting Labour Market Productivity and Social Assistance Inclusiveness.” In Keeping Indonesia Safe From The Covid-19 Pandemic: lessons learnt from the National Economic Recovery Programme, edited by Sri Mulyani Indrawati, 291-317, Singapore: ISEAS Publishing, 2022.

[10] SMERU, “Accelerating Digital Skills Development in Indonesia”. The SMERU Research Institute, 2022.

[11] International Labour Office, “Anticipating and Matching Skills and Jobs”, 2015.

[12] OECD, “Enhancing Equal Access to Opportunities for All. Paris”, OECD Publishing, 2020.

[13] World Bank. “How digital public infrastructure supports empowerment, inclusion, and resilience”, World Bank Blogs, 2023.

[14] G20 Saudi Arabia, “G20 Support to COVID-19 Response and Recovery in Developing Countries Including Africa, Least Developed Countries (LDCs) and Small Island Developing States (SIDS)”, 2020.

[15] G20 Italy, “G20 Policy Principles to ensure access to adequate social protection for all in a changing world of work 2021”.

[16] G20 Indonesia, “G20 Roadmap for Stronger Recovery and Resilience in Developing Countries, including Least Developed Countries and Small Island Developing States”, 2022.

[17] Cyrus Network, “Telesurvei Persepsi Penerima Program Kartu Prakerja terhadap Penyelenggaraan Program Kartu Prakerja”, 2021.

[18] Elan Satriawan, Raden Muhammad Purnagunawan, I Gede Putra Arsana, Ekki Syamsulhakim, Nurzanty Khadijah, Eflina Sinulingga, Martha Safitri, Rachmat Reksa Samudra, and Ben Satriana. “Kartu Prakerja: Indonesia’s Digital Transformation and Financial Inclusion Breakthrough”, 2022.

[19] Meikha Azzani, Martha Hindrayani, Daniera Nanda, and Cahyo Prihadi, “Driving inclusion and resilience through multichannel government-to-person payment: lessons learned from Indonesia’s Kartu Prakerja.”, 2022.

[20] Elan Satriawan, Raden Muhammad Purnagunawan, I Gede Putra Arsana, Ekki Syamsulhakim, Nurzanty Khadijah, Eflina Sinulingga, Martha Safitri, Rachmat Reksa Samudra, and Ben Satriana. “Kartu Prakerja: Indonesia’s Digital Transformation and Financial Inclusion Breakthrough”, 2022.