Task Force 6: Accelerating SDGs: Exploring New Pathways to the 2030 Agenda

Abstract

Women spend 3X more time than men on unpaid care work (UCW) globally, with significant differences across the G20 countries. For example, while Indian women spend about 8X more time on care work than men, women in Canada spend about 1.5X more. This gendered division of responsibilities manifests in market failures in labour markets, hinders women’s access to education, and prevents women from joining and remaining in the workforce.

The G20 economies have committed to reducing gender gaps in labour markets by 25 percent by the year 2025. Recognising, reducing, and redistributing UCW and addressing gender gaps in care work is essential to facilitate women’s participation in formal labour markets. This Policy Brief presents recommendations for the G20 countries to invest in building care economies, including care leave provisions, financial incentives to employers and families, care infrastructure investments such as childcare and elderly care facilities, leveraging private-public partnerships (PPPs), and incentivising investments in community-based organisations (CBOs).

1. The Challenge

Across the world, on average, women and girls deliver 70 percent of paid and unpaid care hours and 75 percent of UCW,[1] which is three times more than men.[2] The COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated the cost, risks, and gender inequities in UCW, with women performing an additional 512 billion hours of UCW in 2020.[3]

The gendered division of UCW within households hinders women and girls’ access to education and employment opportunities, denies them equitable and just wages, and consigns many to an inter-generational cycle of poverty and dependency, with high vulnerability to economic and environmental shocks.

By not valuing UCW and fully accounting for the economic contributions of women and girls in standard national accounting measures, including gross domestic product (GDP), structural inequities are perpetuated. The undervaluation and unrecognition of women’s care work has resulted in labour market failures, manifesting in at least four ways:

- Women experience time poverty, i.e., they have less time than male counterparts for paid work, leisure, education, etc.

- Women find their labour force participation options constrained. Cross-country estimates from the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) (2014) find that a two-hour increase in unpaid labour commitments correlates with a 10 percentage-point decrease in female labour force participation rates (FLFPR).[4]

- Women experience motherhood penalties while fathers experience wage premiums. In most G20 economies, mothers tend to earn less than women without children. The penalty can be as high as 10 percent in Argentina and China, and go up to 30 percent in Turkey.[5] Conversely, men with children tend to earn higher than men without children.

- Care work continues to be undervalued even when performed by service providers outside the household. Consequently, care jobs offer low pay and are often informal.

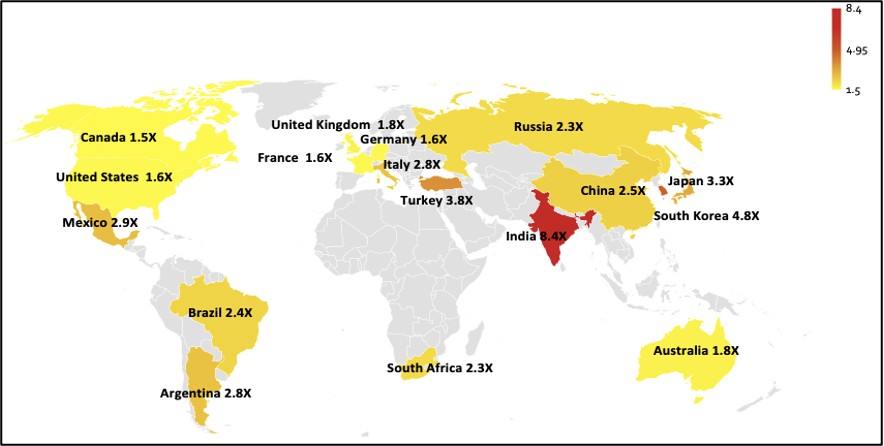

Assessing gender gaps in UCW across the G20 (Figure 1) reveals significant differences across countries, with higher gender gaps in emerging economies. For example, the disparity in UCW undertaken by men and women is 1.5X in Canada compared to 8.4X in India. One of the reasons for this is a sustained focus on investing in care infrastructure and policies, including state-sponsored parental leaves and subsidised care in developed economies. Amongst the emerging economies, Latin American countries are advancing proposals to create comprehensive care schemes.[6]

Figure 1: Gender Gaps in UCW in the G20 Countries

Note: Data for Indonesia and Saudi Arabia and disaggregated data for the European Union are not available. Data for Brazil and Russia have been derived from the World Bank and data for India is from the Government of India’s Time Use Survey 2019.

Source: ILO (2018)[7]

2. The G20’s Role

Gender gaps in UCW result in increased time poverty for women, ultimately leading to low FLFPR across the G20 economies. Globally, the lack of affordable care for children or family members leads to a decrease in women’s chances of participating in the labour market by almost 5 percentage-points in developing countries and 4 percentage-points in developed countries.[8] In Indonesia, almost 40 percent of working women do not work after marriage or childbirth, with half of them citing family-related reasons.[9] Qualitative studies from India reveal that the burden of UCW inhibits women’s ability to work. [10]

Enhancing female labour force participation in the G20 countries will foster socio-economic development. Per the World Bank’s Gender Employment Gap Index (GEGI), countries stand to increase their GDP by up to 20 percent if gender employment gaps were closed.[11]

Investments in care infrastructure and services are instruments for rebalancing the gender gap in UCW and can foster economic growth and job creation, particularly for women. In 2017, the International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC) estimated that an investment of 2 percent of the GDP in the health and care sector would generate increases in overall employment ranging from 1.2 percent to 3.2 percent, translating to approximately 24 million new jobs in China, 11 million in India, 2.8 million in Indonesia, 4.2 million in Brazil, and just over 400,000 in South Africa.[12]

A 2022 study by the International Labour Organisation (ILO) estimated that investments in universal childcare and long-term care services have the potential to generate up to 299 million jobs by 2035, of which 78 percent are expected to go to women.[13] The study showed that instituting universal childcare, paid childcare leave, breastfeeding breaks, and long-term care services would reduce the global gender gap in employment by around 7.5 percentage-points and almost completely close the gap in a third of the countries. Further, GDP would increase by 3.6 percent, with larger increases in African economies, as the employment created would increase tax revenue, ultimately reducing the total funding requirement of care policy packages.

As the G20 countries constitute a mix of advanced and emerging economies, accounting for 66 percent of the world’s population and ~85 percent of global GDP, they are well placed to address care economy challenges and generate solutions that can generate significant impact within and beyond the G20.[14]

In Brisbane in 2014, the G20 leaders pledged to reduce the gender gap in labour force participation by 25 percent by 2025.[15] In 2022, care economy challenges were taken up as a priority area by the W20 and the second G20 Ministerial Conference on Women’s Empowerment in Indonesia, where care work was declared a shared responsibility between men and women, as well as the responsibility of countries and societies. To implement these goals, the Bali G20 Leaders’ Declaration committed to address the unequal distribution in paid and UCW in November 2022, positioning care work as a priority for economic growth.[16]

Going forward, the G20 countries can reduce the existing burden of care on women by focusing on effective policies for strengthening and expanding resilient care systems and building political will and international coordination.

3. Recommendations to the G20

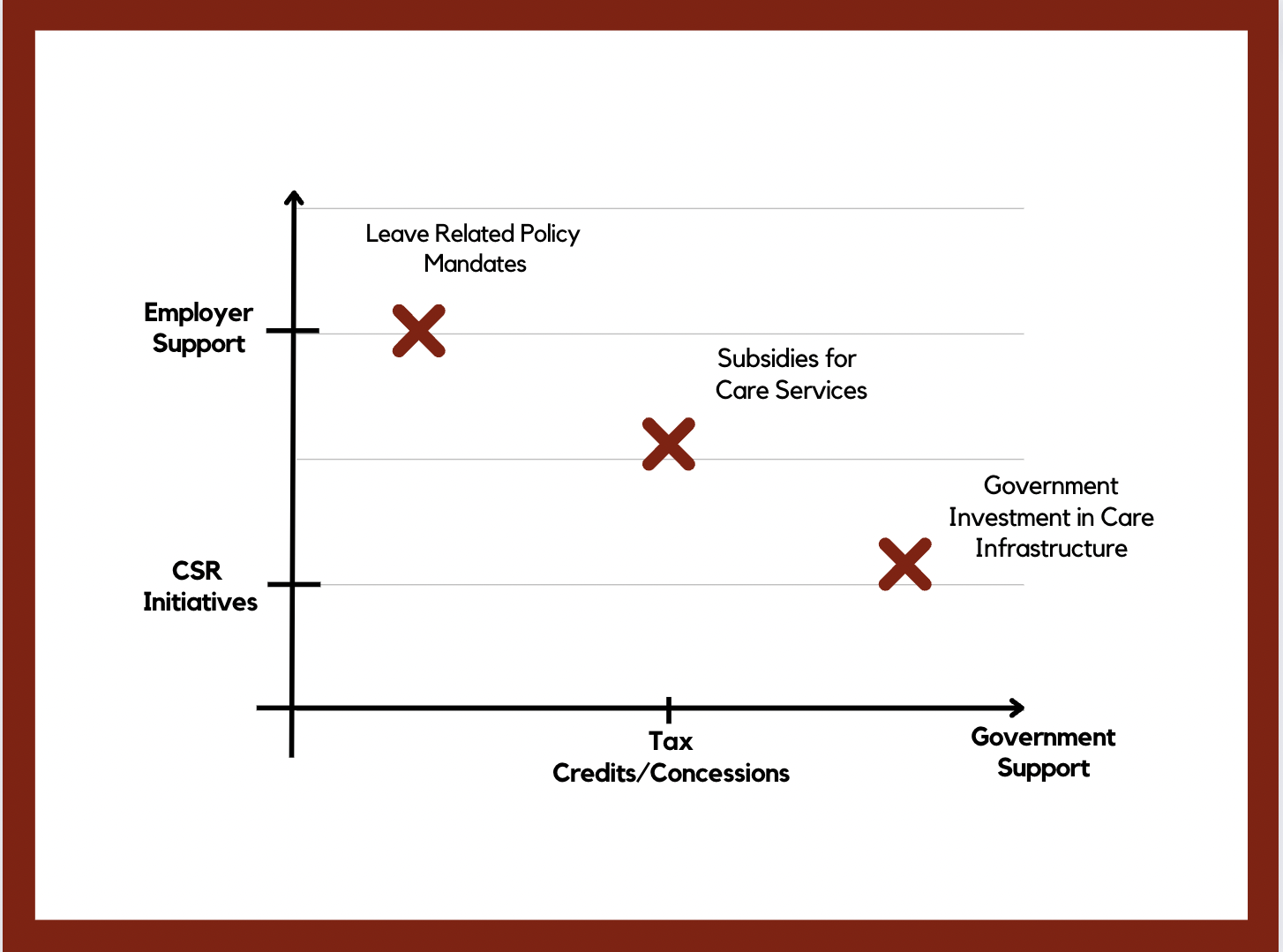

The G20 economies should commit to affirming care as “a critical social good and an essential human right.”[17] PPPs can be a key instrument in developing workable care service delivery models. Governments and the private sector can become equal partners in the care economy, playing complementary roles across three types of interventions in the care economy (Figure 2), as follows:

- Leave and benefits policies

- Subsidies for care services

- Investment in care infrastructure

Figure 2: Three Types of Care Economy Policies

Note: This figure shows government vs. private contribution in each of the three types of care economy interventions.

Source: Authors’ own

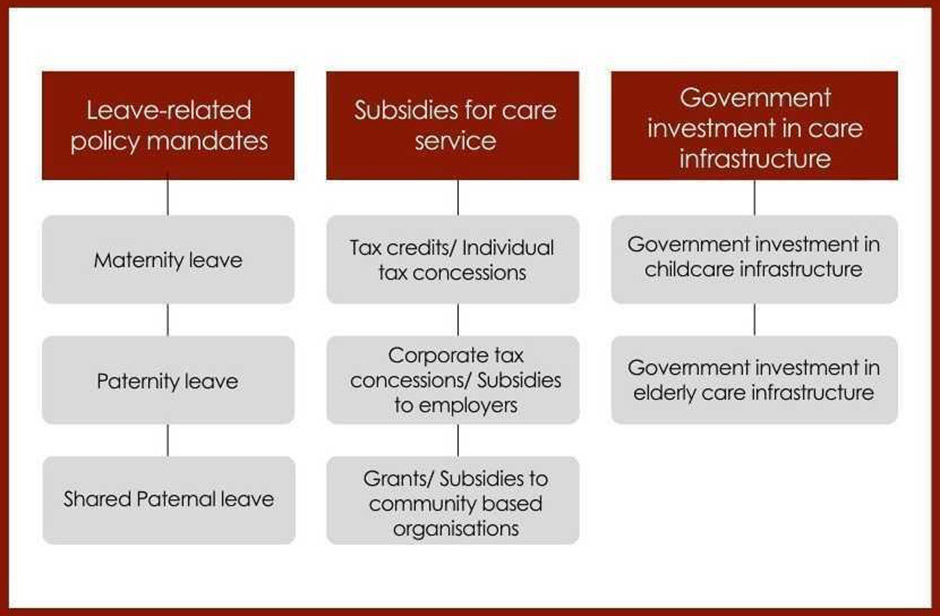

Figure 4: Framework for Care Economy Interventions

Note: This figure shows the sub-categories of each of the three types of care economy interventions.

Source: Authors’ analysis

Leave-related policies

Studies suggest that providing new parents with paid time off contributes to the healthy development of children, improves maternal health, and enhances families’ economic security.[18] For instance, a study on the impact of paid parental leave on labour market outcomes in 30 OECD countries found that extensions of paid leave increase the female-male working hours ratio (0.5-1.8 hours per week).[19]

- Maternity leave: All countries in the G20, barring the USA, have legal provisions mandating paid maternity leave. Typically, maternity leave varies between 10 and 20 weeks, with some exceptions.[a] In over 10 countries, the government also provides some level of financial support for the provision of maternity leave.

- Paternity leave: Most G20 economies (except India, USA, China,[b] Canada,[c] Russia, and Japan) also have statutory entitlements for paid paternity leave, in the range of 2-30 days.

- Shared parental leave: Less than 50 percent of the G20 countries have legal provisions that offer parental leave and partially fund benefits to the primary caregiver, regardless of their gender.

The G20 countries can move towards frameworks that favour gender-sensitive parental leaves rather than only long maternity leaves (with short paternity leaves). Ideally, gender-sensitive parental leaves should promote shared responsibility by encouraging mothers and fathers to take leave periods of equal length. Gender-sensitive parental leaves can reduce the reinforcement of stereotypes that cast the mother as the primary caregiver. The length replacement rate and the timing of leave would need to vary depending on the fiscal capacity of each country.

Countries may use a combination of employer and employee contributions, insurance, and public funding to cover childcare leave costs. Policies which place the onus of providing benefits purely on the employer may end up adversely impacting women in the labour market, as evidenced by India’s Maternity Benefit (Amendment) Act 2017.[20] Thus, the G20 countries can work to find solutions for cost-sharing with the private sector for parental leave.

Additionally, countries should explore options for extending leave coverage to informal workers, such as through parental cash transfers. This is particularly important in the Global South, where high rates of informality often limit workers’ access to traditional parental leave policies. Following the ILO’s (2021) guidelines, countries could ensure non-contributory parental benefits through cash transfers. Some countries, such as Argentina, provide cash transfers to pregnant women through the Universal Pregnancy Allowance, which offers a small sum each month to mothers. Argentina’s care policies, including cash transfers and early childhood care services, have had a strong economic impact with an associated GDP growth of 0.7 percent and 5.3 percent and an increase in total employment from 0.7 percent to 6.4 percent, according to a 2019 study.[21] These cash transfers could be raised to at least the minimum wage and be extended to both mothers and fathers.

Subsidies for care services

For the G20, subsidies for availing care services take the form of individual tax credits for parents and tax concessions to encourage businesses to offer childcare benefits to employees. For instance, parents in the USA are eligible for various tax credits and deductions depending on the child’s age.[22]

While tax subsidies are more common in developed countries, they are slowly being introduced in developing countries. In Brazil, employers have the option to offer an additional maternity leave of two months and deduct the amount paid during this period from their corporate income tax.[23] Argentina’s three-pillar system supports families facing unemployment and informality with tax concessions and cash transfers.[24]

The G20 governments can consider providing financial incentives to employers who encourage the reduction and redistribution of care work responsibilities amongst their employees through corporate tax credits. For instance, employers who provide care services such as breastfeeding/lactation rooms, parking facilities for pregnant women, offer care work leaves, and support employees by hiring care service providers for childcare and elderly care can be rewarded through tax breaks. Moreover, governments can offer higher deductions for small business owners providing support for care work.

Government investments in care infrastructure

As noted in Section 3, care economy investments can be important drivers of socio-economic growth across the G20 economies. Governments may consider public investment in care infrastructure and services to realise these socio-economic development opportunities.

a. Increase spending on childcare and elderly care facilities

The G20 countries, particularly developing economies, need to expand access to better-quality, affordable, and easily accessible care for children and the elderly, which necessitate increased government spending on care infrastructure, particularly in rural and underserved areas.

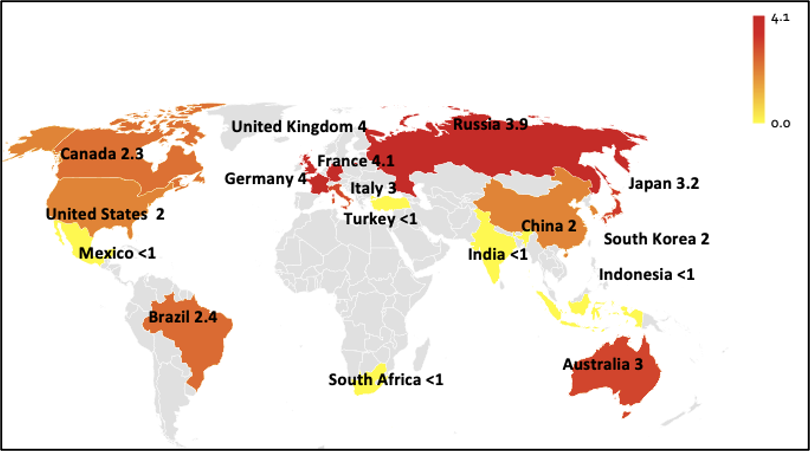

In 2018, the G20 countries were spending between 1 percent and 4.1 percent on selected care policies (Figure 3). Amongst the developed countries, investment as a percentage of GDP ranges between 2 percent and 4.1 percent, whereas for developing countries, it ranges from less than 1 percent to 3.9 percent.[25]

Figure 3: Care Expenditure as Percentage of GDP Across the G20 Countries

Source: ILO Data, 2018

Note: Expenditure includes pre-primary education; long-term care services and benefits; and maternity, disability, sickness, and employment injury benefits.

In recent years, G20 economies like Canada, Germany, China, and the United Kingdom have been actively investing in care infrastructure to build a resilient care ecosystem. The UK announced an investment of US$4.87 billion to expand free childcare for eligible working parents to address the barriers of high childcare costs.[26] Germany allocated US$590 million in 2020 and an additional US$590 million in 2021 to create new childcare facilities and refurbish existing ones.[27] Saskatchewan in Canada announced an investment of US$44 million to support early learning and childcare centres.[28] China has proposed to invest US$5.1 billion to build retirement facilities to support its elderly care system.[29] Going forward, developing economies across the G20 should strive to enhance their fiscal investments in the care economy.

b. Skill training and formalisation of current care work structures

Care work and domestic work are characterised by a high degree of informality, especially among women workers.[30]

To ensure decent and formal working conditions for care workers, the G20 member states could consider strengthening policy, legal, and regulatory frameworks, including ratifying the C189 convention.[d]

There is a need to devise better organisational frameworks with comprehensive job roles and payment bands commensurate with skills, duty hours, and experience for care workers. Skilling programs for care economy workers can be devised and work experience and skill training-based certifications can be introduced to institute seniority levels and specialisations amongst care workers and facilitate the movement of care workers between the G20 countries, as is being done in developed economies like the UK and Canada. Skilling programs for care economy workers can be devised and work experience and skill training-based certifications can be introduced to institute seniority levels and specialisations amongst care workers and facilitate the movement of care workers between the G20 countries, as is being done in developed economies like the UK and Canada. In the UK, private employers can provide training to care workers to obtain entry-level certifications and for further qualifications. In Ontario, Canada, a comprehensive registry has been created to ensure greater public protection and personal care worker accountability. The registry only accepts workers who are deemed qualified to provide competent and safe care.[31]

c. Leveraging public-private partnerships

For sustained and gender-inclusive post-pandemic recovery, G20 countries can devise policy and regulatory frameworks to operationalise PPPs for the provision of care services, as well as for greenfield/brownfield care infrastructure on a pilot basis, including model concession agreements for care infrastructure facilities such as childcare facilities or elderly care facilities. These frameworks should identify risk mitigation mechanisms and financing models relevant to the care sector and define key performance indicators. Following pilots, sufficient evidence may be generated to assess the impact and effectiveness of these models.

d. Incentivising investing in community-based organisations and social enterprises

Multiple G20 countries have provisions which direct grants towards local CBOs, particularly in the informal and rural sectors. For example, Australia supports approved providers of aged care with financial support.[32]

Governments can prioritise investments in rural and underserved areas to support CBOs providing innovative care solutions. A successful example of community-run care services (CCCs) comes from India which, if provided government funding, could scale and replicate its solution. Nikore Associates’ consultations with Apnalaya, a CBO run by women in Mumbai’s informal settlements, revealed how CCCs increased women’s workforce participation and provided many women with a source of employment.[33]

Private enterprises can also provide CBOs with financing as part of their Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) budgets. Through partnerships with formal sector enterprises, these CBOs may provide in-situ care facilities to workers in factories and other work locations. Such collaborations can allow CBOs to scale up their operations, helping them become financially viable social enterprises and increase access to care services in the rural and informal sectors. An example is Tata Trusts’ initiative to improve nutritional outcomes for children by supporting the maintenance of existing anganwadis (childcare centres) in rural India.[34]

e. Collect gender-disaggregated data on care work

Regular gender disaggregated Time Use Surveys (TUS) are essential across the G20 countries, which include wide national and local coverage, more descriptive questions, and improvements in methodology to capture different types of UCW activities.

In addition, governments can track the quantum of fiscal investments in care infrastructure and the number of care jobs being generated. The G20 countries can also consider working together to establish common frameworks for data collection that may be actively tracked on an annual basis and discussed at G20-supported workshops and conferences.

An example of such a methodology is from Mexico, which has a system of data collection using Household Satellite Accounts which measures the time use characteristics of various demographics and has been used to formulate policies on care.[35]

4. Conclusion

The disproportionate burden of UCW has resulted in a market constraining women’s workforce participation. Correcting these market failures requires a coordinated effort from key stakeholders across the G20.

Appendix A

To supplement the recommendations provided in this Brief, five global best practices have been presented as case studies in this appendix.

| Case Study 1 | Community Childcare Centres (CCCs) by Apnalaya in India |

| Country | Mumbai, India |

| Year started | 2014

|

| Implementing agency | Apnalaya, a community-based organisation |

| About the model | A community-based organisation supporting childcare infrastructure in Mumbai’s informal settlements. |

| Key features | Apnalaya empowers women by building capacity for financial independence and entrepreneurship. In 2014, as an alternative to Anganwadi services (which were unavailable for long hours in urban areas), Apnalaya supported women entrepreneurs across several informal settlements in Mumbai to launch CCCs. Based on a social enterprise model, CCCs provide affordable childcare services, enable mothers to work, keep children safe, and generate employment opportunities for women in the community. |

| Impact of the program

|

Consultations with Apnalaya revealed that CCCs improve women’s workforce participation: 79 percent of users were working mothers, and following the closure of CCCs during the pandemic, 14 percent of all users were forced to quit their jobs owing to an increased burden of childcare. Additionally, CCCs serve as a source of employment. For 50 percent of CCC operators, this was their first job. It is seen that women micro-entrepreneurs gained control of their income and could thus make decisions with regard to household expenditure. |

Source: Nikore Associates[36]

The Indian government has launched a number of programs and schemes to provide care services across the country. The National Health Mission by the Government of India envisages universal access to equitable as well as affordable and quality healthcare services in both urban and rural areas.

Accredited Social Health Activist (ASHA) and Anganwadi Workers (AWW) are honorary volunteer community health workers working under the National Health Mission. Their role includes providing maternal and childcare services and creating awareness and mobilisation for immunisation and nutritional care.[37]

The Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS) Scheme, launched on 2 October 1975, is one of the flagship programmes of the Government of India, focusing on children and nursing mothers. Under ICDS, anganwadi centres are the focal point for implementation of all the health, nutrition, and early learning initiatives.

| Case Study 2 | Australia’s Dad and Partner Pay Policy |

| Country | Australia |

| Year started | 2013 |

| Implementing agency | Australian Government Department of Social Services |

| About the model | To increase fathers’ participation in child-rearing, Australia’s paid parental leave scheme was changed in 2013 to include a ‘Dad and Partner Pay’ for up to two weeks (in addition to the existing Parental Leave Pay for 18 weeks for the primary carer), paid at the rate of the national minimum wage. |

| Key features | Eligibility: To be eligible for Dad and Partner Pay, the person must be the child’s biological or adoptive father, or the partner of the child’s mother, and have worked for at least 10 of the 13 months prior to the birth or adoption of the child.

Payment amount: The payment is currently set at A$719.35 per week (as of September 2021), before tax, for a maximum of two weeks. The payment is taxable income and subject to normal tax deductions. Timing of payment: The payment can be claimed at any time within the first 52 weeks after the child’s birth or adoption, but it must be claimed within 52 weeks of the birth or adoption of the child. Work restrictions: The person must not be working or taking paid leave during the period they receive Dad and Partner Pay. Impact on other entitlements: Receiving Dad and Partner Pay may impact a person’s eligibility for other government payments, such as Family Tax Benefit, and may also affect their employer-provided entitlements. |

| Impact of the program | · Financial support to take leave at the time of a child’s birth can give fathers a greater role that extends beyond the financial, encouraging them to engage immediately in care tasks. The leave can also give fathers the chance to develop a co-parenting relationship early, to enable a lived experience that reshapes the notions of fatherhood, and to increase their practical and emotional investment in their infant’s care.

· Additionally, private organisations which supplement this leave with their own shared parental leave policies report positive uptake. · Deloitte has reported an increase in the proportion of male users of its parental leave scheme, from 20 percent to 40 percent. PwC also reported an increase in the percentage of men using its parental leave scheme, to more than 45 percent. |

Source: Grattan Institute, 2021[38]

Apart from this, the Department of Health and Aged Care, Government of Australia, is providing aged care subsidies for approved providers of home care, residential care, and flexible aged care. Subsidies are paid on behalf of each person receiving government-subsidised aged care. The policy also includes funding for the provision of training and education to aged care workers to improve their skills and knowledge in providing care to older Australians. According to the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW), in the financial year 2019-20, over one million people were accessing aged care services in Australia.[39]

| Case Study 3 | Parental Benefits in Sweden |

| Country | Sweden |

| Year started | 1995 |

| Implementing agency | Swedish Social Insurance Agency |

| About the model | Each parent in Sweden is entitled to 90 personal days (or more than 12 weeks) of leave with 80 percent of their wages and also entitled to 480 shared days, out of which both parents have 240 days each. |

| Key features | During the child’s first year, there is an opportunity for both parents to take parental leave benefit during the same period for no more than 30 days (so-called ‘double days’). 384 days of parental benefit must be taken before the child’s fourth birthday. The remaining 96 days can be saved and taken, at the latest, before the child turns 12 or until the child finishes the fifth grade. |

| Impact of the program | · For children born in 1995 onwards, 77 percent of fathers have used parental leave before the child reached 4 years of age.

· Through such policies, Sweden has been able to combine relatively high fertility levels with high female labour force participation rates and low child poverty. |

Source: Institute for Future Studies, 2005[40]

| Case Study 4 | Expansion of Day Centres for Children in Germany |

| Country | Germany |

| Year started | 2020-21 |

| Implementing agency | Government of Germany |

| About the model | As part of Germany’s Investment Programme, known as Childcare Financing, the federal government is investing billions in the expansion of child day care facilities. |

| Key features | · In 2021, 1 billion euros were allocated for the programme to create new childcare facilities and enhance existing ones.

· 90,000 new childcare facilities to be established. · In addition, further funds amounting to 1.5 billion euros were allocated for the expansion of space for all-day care in grades 1 to 4 and 0.5 billion euros as an investment in the digital equipment of schools. |

| Impact of the program | · Promotes better childcare and parental outcomes

· Promotes increased access to childcare facilities and increases productivity · A report by the OECD found that the expansion of childcare services has contributed to reducing the gender employment gap in Germany by increasing the participation of women in the labour force. |

Source: European Commission[41]

| Case Study 5 | Maternity Leave Policy in Argentina |

| Country | Argentina |

| Year started | Regulated under provisions in the 1974 National Laws on Contact of Employments, with amendments in subsequent years |

| Implementing agency | Government of Argentina – National Social Security Organisation |

| About the model | · The government fully funds the maternity leave cash benefits and provides 13 weeks of maternity entitlement.

· After the maternity leave period, mothers can also take an unpaid leave of absence of three to six months. · There are also provisions for disabilities. In case of children with Down Syndrome, the paid maternity leave is extended by 6 months. |

| Impact of the program | · Funded maternity leave policy enables mothers to maintain job security as well as improves quality of life for the mother and the child.

· Collective bargaining and private sector initiatives have enhanced the efficacy of the law, for example under the Agrarian Labour law, temporary workers are also covered under the same conditions. · The Family and Business Conciliation Centre (CONFyE) has reported multiple innovative solutions such as reduced working hours for returning mothers for full pay, and support for flexible working arrangements. |

Source: Leave Network, 2021[42]

Attribution: Mitali Nikore et al., “Leveraging Care Economy Investments to Unlock Economic Development and Foster Women’s Economic Empowerment in G-20 Economies,” T20 Policy Brief, June 2023.

Endnote

[a] The UK mandates 52 weeks of statutory maternity leave, but maternity pay entitlements are only provided for 39 weeks.

[b] Statutory entitlement nationally does not exist; however, some provinces choose to give 10-30 days of paternity leave.

[c] There is no statutory paternity leave in Canada, except in Québec. Paternity leave in Canada is a part of the parental leave, which means that both parents can use this time off together, but at least 5 weeks are reserved for “daddy days”.

[d] The C189 convention is an ILO convention setting labour standards for domestic workers.

[1] “Not all Gaps are Created Equal: The True Value of Care Work,” Oxfam International , 2023.

[2] Laura Addati et al., Care Work and Care Jobs for the Future of Decent Work (Genèva: International Labour Organisation (ILO), 2018).

[3] “Progress on the Sustainable Development Goals,” UN Women, 2022.

[4] Gaëlle Ferrant, Luca Maria Pesando, and Keiko Nowacka, “Unpaid Care Work: The Missing Link in the Analysis of Gender Gaps in Labour Outcomes,” OECD, December 2014.

[5] International Labour Organization (ILO), “Global Wage Report 2018/19: What Lies Behind Gender Pay Gaps,” 2018.

[6] INMujeres and UN Women, “Bases Para Una Estrategia Nacional de Cuidados,” 2018.

[7] Addati et al., Care Work and Care Jobs for the Future of Decent Work

[8] ILO, World Employment Social Outlook (Geneva: International Labour Organisation (ILO), 2017).

[9] Anna O’Donnell, “How Investing in Childcare Drives Economic Growth for Indonesia,” World Bank Blogs, 2023.

[10] Nikore et al., “India’s Missing Working Women: Tracing the Journey of Women’s Economic Contribution Over the Last Seven Decades, and During COVID-19”

[11] Steven Michael Pennings, “A Gender Employment Gap Index,” 2022.

[12] Jérôme De Henau, Susan Himmelweit, and Diane Perrons, “Investing in the Care Economy,” ITUC, 2017.

[13] Laura Addati, Care at Work: Investing in Care Leave and Services for a More Gender Equal World of Work (Geneva: International Labour Organization, 2022).

[14] Government of India, “The Group of Twenty (G20),” accessed 2023.

[15] “Women at Work in G20 Countries: Progress and Policy Action Since 2018: International Labour Organization (ILO),” International Labour Organization (ILO),2019.

[16] G20 Bali Leaders’ Declaration, November 2022.

[17] Clare Coffey et al., “Time to Care: Unpaid and Underpaid Care Work and the Global Inequality Crisis: Oxfam,” Oxfam International, 2020.

[18] Christopher J. Ruhm, “The Economic Consequences of Parental Leave Mandates: Lessons from Europe,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 113, no. 1 (Feb 1, 1998): 285-317. doi:10.1162/003355398555586.

[19] Olivier Thévenon and Anne Solaz, “Labour Market Effects of Parental Leave Policies in OECD Countries,” OECD.

[20] Purna Banerjee, Shreya Biswas, and Debojyoti Mazumder, “Maternity Leave and Labour Market Outcomes,” July 4, 2022.

[21] Gala Diaz Langou and Florencia Caro Sachetti. “Achieving “25 by 25”: Actions to Make Women’s Labour Inclusion a G20 Priority,” CIPPEC, 2018.

[22] “Child Tax Credit,” The White House, accessed April 2023.

[23] “Consolidation of Laws of Work and Related Standards,” Federal Senate, 2017, (senado.leg.br)

[24] “Argentina’s Universal Child Allowance,” UNESCAP, accessed April 2023.

[25] Addati et al., Care Work and Care Jobs for the Future of Decent Work

[26] “30 Hours Free Childcare,” Government of United Kingdom, accessed April 2023.

[27] “Childcare Financing 2020-2021,” Federal Ministry of Family Affairs, accessed April 2023.

[28] “Government Announces $44 Million in New Grants for Child Care Facilities,” Government of Saskatchewan, January 31, 2023.

[29] Marion F. Krings et al., “China’s Elder Care Policies 1994-2020: A Narrative Document Analysis,” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 10 (May 18, 2022): 6141, doi:10.3390/ijerph19106141.

[30] International Labour Organization (ILO), “Formalizing Domestic Work,” 2016.

[31] OECD, “Who Cares? Attracting and Retaining Care Workers for the Elderly,” 2020.

[32] “Aged Care Subsidies and Supplement,” Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care, April 2023.

[33] Coffey Clare et al., “Time to Care,” Oxfam, 2020.

[34] “Centres for Care,” Tata Enterprises, accessed April 2023.

[35] National Institute of Statistics and Geography, “Unpaid Household Work Satellite Account of Mexico,” UN Stats, 2022.

[36] Mitali Nikoreet al., “India’s Missing Working Women: Tracing the Journey of Women’s Economic Contribution Over the Last Seven Decades, and During COVID-19,” Journal of International Women’s Studies 23, no. 4 (2022).

[37] Nikore et al., “India’s Missing Working Women”

[38] Danielle Wood, Owain Emslie, and Kate Griffiths, Dad Days (Grattan Institute Support, 2021).

[39] Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, Australian Government, 2021.

[40] Ann-Zofie Duvander, Tommy Ferrarini, and Sara Thalberg, “Swedish Parental Leave and Gender Equality,” Institute for Future Studies, 2005.

[41] European Commission, “Germany’s Recovery and Resilience – Supported Projects”.

[42] International Network on Leave Policies and Research, “Argentina,” 2021.