Task Force – 6: Accelerating SDGs: Exploring New Pathways to the 2030 Agenda

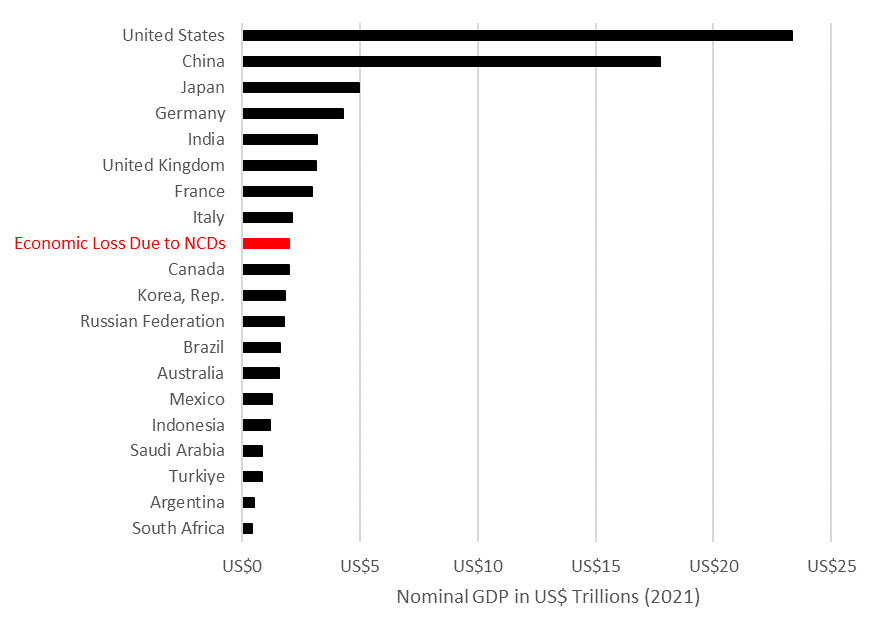

Non-communicable diseases (NCDs) cause 41 million preventable deaths each year,[1] approximately six times the number of people who have died from COVID-19 so far. The estimated economic loss resulting from the five most common NCDs is US$2 trillion annually,[2] more than the nominal GDP of most countries in the G20. With NCDs accounting for the leading causes of death in most G20 countries, the group has an imperative to do more to protect its populations from this problem. It also has the power to make a difference.

The interventions needed are clear—including cross-sectoral public policies to prevent NCDs, earlier diagnosis and treatment to improve patient outcomes, and healthcare system sustainability—but action has been slow. This policy brief considers the magnitude of the NCD problem, the threat it poses to the G20, and how G20 leadership can protect population health and economic development by acting on this issue.

1. The Challenge

The lack of prioritisation and investment in non-communicable diseases (NCDs) is allowing a silent crisis to undermine health and well-being, exacerbate inequities and poverty, and impede economic growth and development.

Cost of underinvestment in NCDs is substantial

Every two seconds a person dies prematurely from an NCD.[3] NCDs are estimated to be responsible for nearly three-fourths of all deaths globally, killing 41 million people every year. In contrast, COVID-19 is thought to have caused 6.9 million deaths since the start of the pandemic.[4] NCDs account for approximately 70 percent of all deaths per year in most G20 countries.[5] About 40 percent of NCD deaths are premature (i.e., they occur before the age of 70) and the impact of losing individuals in their prime productive years reverberates across their families, societies, and economies.[6] The burden of NCDs, which include cancer, cardiovascular disease (CVD), chronic respiratory diseases (CRD), diabetes, and mental illnesses goes beyond death, causing significant morbidity and disability as well. One-fifth of the world’s population is living with an NCD,[7] and up to 94 percent of people who died from COVID-19 were living with NCDs.[8] NCDs are considered among the greatest threats to the resiliency and sustainability of healthcare systems.[9] The burden of NCDs extends beyond mortality, morbidity, and healthcare, also undermining economic growth and development. Treatment for and outcomes from the top five most common NCDs are estimated to cost over US$2 trillion annually, greater than the median of individual G20 country GDPs (see Figure 1).[10] NCDs impede achievement of universal health coverage (UHC) by exacerbating inequities and driving catastrophic health expenditure. In low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) more than 60 percent of patients with cancer, cardiovascular disease, and stroke experience catastrophic health expenditure,[11] and out of pocket (OOP) spending per visit is estimated to be twice as high for NCDs than for communicable diseases.[12]

Figure 1: Comparison of Total World Economic Loss Due to NCDs Per Year to and Nominal GDPs of G20 Countries (2021)

Source: World Bank Data

Underfunded healthcare systems struggle to adopt and deliver cost-effective interventions

NCDs are caused by a combination of genetic, physiological, environmental, and behavioural factors, many of which are preventable, treatable, or manageable. There is broad consensus and an extensive body of literature on cost-effective, feasible interventions that all countries can undertake to prevent and address the burden of NCDs (see Box 1).[13] These interventions, endorsed by the World Health Organization (WHO), include 13 cross-sectoral public policies to reduce risk factors such as tobacco and alcohol use and promote healthy diets and physical activity, as well as clinical interventions delivered at the primary healthcare and hospital levels, such as the prevention, early screening, diagnosis, and treatment of cancers.[14] Prioritising this set of NCD interventions this decade could avert 39 million deaths and yield US$2.7 trillion in economic benefits, with benefits outweighing costs 19-to-1.[15]

Box 1: NCD Best Buy Interventions[16]

|

Several global policy commitments made through the UN High Level Meetings on UHC, the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, and other platforms underscore the importance of addressing NCDs and set tangible, attainable goals.[17] Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 3 includes target 3.4, which calls for the reduction of premature mortality from NCDs by one-third by 2030 through prevention and treatment, and target 3.8, which calls for UHC. Moreover, achieving SDG 3 and NCD targets can help stimulate progress towards other SDGs, including SDG 8 to promote decent work and economic growth and SDG 9 to foster innovation, and create further cyclical progress in health (i.e., a positive feedback loop). Yet progress towards these commitments is slow. For example, less than two-thirds of countries globally have breast and cervical cancer screening programmes, and those that do are reaching less than 50 percent of their target populations.[18] Similarly, less than two-thirds of countries have early detection programmes or guidelines to strengthen early diagnosis of cancer symptoms at the primary healthcare level.[19] Further, the COVID-19 pandemic has set back progress towards SDG 3. More than 40 percent of countries reported increased backlogs for screening, diagnosis, and treatment of cancers and other NCDs due to service disruptions during the pandemic.[20] The impact of later detection and treatment (i.e., poorer health outcomes, higher costs, and resource utilisation) on already overstretched healthcare systems and communities will persist for decades.

How to sustainably invest in NCDs

The lack of funding for NCDs is unacceptable given the billions of people impacted.[21] It is estimated that achieving SDG 3.4 worldwide requires US$140 billion in new spending over 2023 to 2030 (equivalent to US$18 billion per year).[22] The WHO has estimated that an additional investment of just US$0.84 per person per year to cover the 16 most cost-effective interventions could greatly reduce the burden of NCDs in low- and lower-middle income countries.[23] However, despite the link between NCDs and pandemic preparedness, health security, and economic development, efforts to secure investment for NCDs and the future health of communities and economies is falling short.[24]

Data on public sector investment in NCDs is limited,[25] and available data indicates that current levels of investment are insufficient. For example, in Australia, Japan, South Korea, and countries in Europe spending on prevention and public health is less than 3 percent of total health spending.[26] [27] When governments fall short, individual patients carry the burden of paying for NCD services. Available data indicates that private or OOP spending is higher for NCD services at the primary care level than for areas such as infectious diseases and reproductive health.[28] Global development assistance for health (DAH) also reflects the lack of prioritisation and funding for NCDs – ranging from just 0.6 percent to 1.6 percent of total DAH over the last three decades.[29] Governments must ensure that the burden of paying for healthcare does not fall on individual patients and exacerbate inequities and poverty. They need to find ways to continue to increase investment in NCDs, accounting for a higher proportion of GDP and total government spending.

2. The G20’s Role

The G20 leadership is critical to accelerate collective action on the most pressing global health needs. The G20 leadership and action can shine a light on the significant underinvestment in NCDs and catalyse action in its member countries. Representing 70 percent of NCD deaths worldwide,[30] the G20 can signal and encourage governments to take the following three critical actions:

Prioritise investment in NCDs

The G20 can encourage national recognition of NCDs as a political and fiscal priority that should be translated into robust national policies with secured funding. There is still much work to be done in establishing evidence-based policies, targets, and operational plans across the G20 member countries. For example, recent data from the WHO NCD Progress Monitor indicates that seven G20 countries still do not have any or only partial time-bound targets for NCDs to guide their national policies and plans, and 10 G20 countries still do not monitor all key risk factors for the four most common NCDs (including tobacco use, raised blood pressure and total cholesterol, overweight and obesity).[31] Globally, implementation of WHO-recommended policies is stagnating with countries implementing less than 50 percent of policies to address NCDs as of 2021.[32] While more countries have implemented policies to reduce tobacco use and salt consumption, there has been a decline in policies to address other risk factors and in the setting of national NCD policies with targets.[33] Notably, India was the first country to develop specific national targets and indicators aimed at reducing the number of global premature deaths from NCDs by 25 percent by 2025.[34] Countries across the European Union (EU) are currently developing or enhancing national policies, in part reflecting aspirations and guidance set by the EU Beating Cancer Plan (see Box 2).[35] The G20 provides a platform for promoting the use of evidence-based targets (e.g., percentage of eligible population screened, percentage reduction in CVD burden) in national policies and action plans to track progress and demonstrate the impact of investment in NCDs over time.

| Box 2: Robust policies to beat cancer in Italy

Italy is taking a comprehensive, multidisciplinary approach to prevent, detect, and treat cancer. Italy’s National Cancer Plan sets strategic objectives, indicators, and a process for monitoring progress. The plan also seeks to improve digitisation and finalise a national cancer registry to improve evidence-based decision making at the population and patient-level. The plan is being drafted with input from multi-sectoral stakeholders, including national and local governments, health care professionals, patients, and civil society, and is building on existing laws and funding to advance cancer prevention and care. |

Secure sustainable and diversified sources of financing

G20 dialogue and commitment are paramount to increase and sustain financing for NCDs, from both public and private sector sources. As demonstrated by the G20’s efforts on COVID-19 recovery, pandemic preparedness, and climate finance, the G20 is uniquely positioned to successfully advance NCD financing through multi-sectoral dialogue and cooperation. The urgency for G20 countries to identify and allocate alternative funding to achieve UHC and to address NCDs was recognised during the G20 in Indonesia in 2022. It was also recognised that multi-stakeholder approaches, including government leaders, are key to achieving sustainable, innovative funding and access to healthcare, particularly given the complexity of and significant advancements in diagnosing and treating NCDs.

As noted above, several rigorous investment studies have been developed to inform both global and national funding decisions, yet insufficient awareness and prioritisation, a lack of clarity on current investments, and a need for more diverse and sustainable financing models to address budgetary pressures are impeding tangible investment.[36] Shining a light on the lack of budgetary data and the importance of monitoring investment in NCDs is a significant first step in this journey to improve funding and financing for NCDs and an important role for the G20. This includes alignment on what and how to track public sector investment in NCDs through the system of national health accounts. The G20 countries can take lessons learned from the OECD’s Development Assistance Committee decision to implement new reporting codes to better track development assistance for NCDs.[37] The ability to track investment coupled with measurable targets and robust, comprehensive frameworks to evaluate the return on investment can help countries ensure they sustain smart investments in NCDs.

While there is no one-size-fits-all model for sustainable financing for NCDs, leading global and regional institutions have done substantial work to gather evidence and identify best practices on financing models that are sustainable and effective, including earmarking health taxes,[38] enabling supplemental medical insurance (SMI)[39], and testing innovative catalytic models, such as blended financing.[40]

Several G20 member countries have already taken significant steps towards investing better and more in NCDs. For example, Italy’s Fund for Innovative Drugs is helping accelerate access to innovative therapies for cancer and other diseases while also assisting the government more predictably and sustainably manage its resources.[41] Similarly, the Fund to Fight Cancer established in the Brazilian State of Maranhão leverages novel sources of financing to expand and strengthen preventive, diagnostic, and therapeutic services for cancer (see Box 3).[42]

| Box 3: An Innovative Approach to NCD Financing: The Fund to Fight Cancer in Maranhão, Brazil

In response to the high incidences of breast and cervical cancer and few screening facilities in Maranhão, local lawmakers established the Fund to Fight Cancer. The fund leverages funding from alcohol and tobacco taxes and can receive money from other public or private sources. It successfully increased investment in cancer from R$442 million to R$2 billion and increased the number of cancer screening sites in the state from one to six, greatly contributing to public health. |

To help achieve UHC, several countries in Asia are exploring the role of private health insurance as supplemental to public or national health insurance, and many are establishing policy frameworks to enable such models.[43] For example, the Government of Indonesia has identified the potential use of health taxes to partially or fully fund SMI for cancer cares as one solution to overcome the current lack of funding for UHC from the National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS). Multiple stakeholders, including the central and provincial government, universities, and researchers, are collaboratively exploring a demonstration project in West Java Province to finance effective and innovative cancer treatments in addition to NHIS funding by leveraging SMI. The G20 platform provides an opportunity for sharing best practices and promoting policies that enable diverse, sustainable financing.

Investment and action to reduce the burden of NCDs requires a multi-sectoral approach, both across government agencies and across external stakeholders, particularly to develop fiscal, transportation, and built environment policies that can mitigate key risk factors, which contribute to many NCDs. The G20 is well-positioned to bring together leaders from health, finance, pandemic preparedness, transportation, agriculture, education, energy, and development. G20 commitment also signals to global health institutions, bilateral agencies, multilateral development banks, and others providing technical or funding assistance, to prioritise NCDs, align with national plans, and improve investment models for NCDs.

Improve efficient utilisation of funds and resources

In addition to securing more funding for NCDs, G20 dialogue can also highlight how to improve the use of existing resources to deliver better health for money and enhance sustainability. For example, in Brazil, the city of Porto Alegre is collaborating with the City Cancer Challenge (C/Can) to optimise resources for the treatment of cancer patients.[44] C/Can is working across many cities to develop ambassadors to champion better and improved financing for cancer prevention and care and bring new technical and funding partners together. Many countries, such as Mexico, are also leveraging digital technologies (e.g., smartphone tools, telemedicine) to monitor and care for those with NCDs, improving utilisation of resources and quality of care.[45] Continuous monitoring and better use of digital data, telehealth services, and other innovations can help countries optimise resources to achieve the best health outcomes for NCDs.

3. Recommendations to the G20

SDG target 3.4 calls for the reduction of premature mortality from NCDs by one-third by 2030 from 2015 levels, yet the WHO estimates that the annual rate of reduction thus far is just under 1 percent per year.[46] Investing in NCD prevention and care is crucial as the world struggles to achieve SDG 3. It is estimated that implementing the WHO best buy interventions (see Appendix 1) will require an additional investment of US$18 billion globally and necessitate LMICs to spend 20 percent of their health budgets on NCDs. The G20 can accelerate progress toward greater investment in NCDs through the following actions:

Establish a robust multiyear agenda through the Health Working Group to ensure prioritisation of and sustainable investment in NCD prevention and care at the global and national level: The multiyear agenda would enable the G20 to signal to all countries the need to prioritise NCDs, establish timebound targets through national policies and operational plans, and secure funding to implement those plans. As the world begins to look beyond the COVID-19 pandemic, the G20 is uniquely positioned to call attention to and drive such leadership on the silent crisis of NCDs. The Indian Presidency can work with the G20 Troika to establish a robust multi-year agenda through the Health Working Group which can commence activities during the incoming Brazilian Presidency.

Accelerate investment in NCDs by promoting and enabling sustainable, diversified financing models through the G20 Joint Health & Finance Task Force (JHFTF) and the Sustainable Finance Working Group (SFWG): The G20 plays an important role in identifying emerging health and economic threats and initiating constructive policy dialogue and action across ministries of health, finance, and other sectors to avert and mitigate risks. Such leadership is critical to address the burgeoning NCD crisis. Building on their notable leadership on COVID-19 recovery, the Pandemic Fund, and climate finance, we call upon the Italian and Indonesian co-chairs of the JHFTF, SFWG, and participating international institutions to promote and enable improved investment in NCDs by:

- establishing metrics that track health investments and demonstrate the full return on that investment to help sustain and increase funding;

- promoting best practices in traditional underutilised fiscal policies and models for improving domestic resource mobilisation for NCDs; and

- enabling experimentation with diverse and innovative financing models, including impact investing that leverage public and private sector resources and partnerships for NCDs.

We applaud the G20 SFWG for prioritising financing for other SDGs, including impact investing for health.[47] Mirroring the work of the SFWG on climate financing, including raising awareness of different climate financing models, removing policy barriers for innovative climate financing models, and enhancing the role of multilateral development banks and private investors in financing climate efforts,[48] will be invaluable in harnessing a currently fragmented NCD investment landscape.

Further, there are unique opportunities under the Indian Presidency to leverage digital technology for health, including under the T20’s Task Force on Digital Public Infrastructure.[49] The work of this Task Force can support the SDGs, including SDG 3.4 and 3.8 by leveraging digital data to help track investments in health across disease areas, including NCDs, with the goal of evaluating comprehensive return on investment.

Attribution: Julia Spencer, Dennis A. Ostwald, and Hasbullah Thabrany, “Investing in Health and the Economy: Curbing the Crisis of Non-Communicable Diseases,” T20 Policy Brief, July 2023.

[1] “Noncommunicable diseases,” World Health Organization, September 16, 2022, https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/noncommunicable-diseases

[2] “Financing NCDs,” NCD Alliance, accessed July 7,2023, https://ncdalliance.org/why-ncds/the-financial-burden-of-ncds

[3] “About Global NCDs,” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, December 17, 2021, https://www.cdc.gov/globalhealth/healthprotection/ncd/global-ncd-overview.html

[4] WHO, “Noncommunicable diseases.”

[5] Hidechika Akashi et al., “The role of the G20 economies in global health,” Glob Health & Medicine 1, no. 1 (2019): 11-15, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7731051/

[6] WHO, “Noncommunicable diseases.”

[7] NCD Alliance, “Invest to Protect, Geneva, NCD Alliance, 2022, https://ncdalliance.org/sites/default/files/resource_files/NCD%20Financing_ENG.pdf

[8] NCD Alliance, Invest to Protect.

[9] Health Policy Partnership, Out of the Ashes: Why Prioritizing Non‑Communicable Diseases is Central to Post‑COVID‑19 Recovery, London, Health Policy Partnership, 2021, https://www.healthpolicypartnership.com/app/uploads/Out-of-the-ashes-why-prioritising-non-communicable-diseases-is-central-to-post-COVID-19-recovery.pdf

[10] NCD Alliance, “Financing NCDs.”

[11] Stephen Jan et al., “Action to address the household economic burden of non-communicable diseases,” The Lancet 391, no. 10134 (April 4, 2018): 2047-2058. https://www.thelancet.com/pdfs/journals/lancet/PIIS0140-6736(18)30323-4.pdf

[12] Ann Marie Haakenstad, “Out-of-Pocket Payments for Noncommunicable Disease Care: A Threat and Opportunity for Universal Health Coverage,” (PhD diss., Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, 2019), 62-64, http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:41594096

[13] David A. Watkins, et al., “NCD Countdown 2030: Efficient Pathways and strategic investments to accelerate progress towards the Sustainable Development Goal Target 3.4 in low-income and middle-income Countries,” The Lancet 399, no. 10331 (March 26, 2022): 1266–1278. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02347-3

[14] Watkins, et al., “NCD Countdown 2030,” 1268.

[15] Watkins, et al. “NCD Countdown 2030,” 1272.

[16] World Health Organization, Saving Lives, Spending Less: The Case for Investing in Noncommunicable Diseases, Geneva, WHO, 2021, https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240041059

[17] NCD Alliance, Invest to Protect.

[18] World Health Organization, Assessing national capacity for the prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases: report of the 2019 global survey, Geneva, WHO, 2020, https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240002319

[19] WHO, Assessing national capacity for the prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases.

[20] World Health Organization, Global pulse survey on continuity of essential health services during the COVID-19 pandemic. Round 3: Key informant findings from 129 countries, territories and areas, Geneva, WHO, 2022, https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/global-pulse-survey-on-continuity-of-essential-health-services-during-the-covid-19-pandemic-Q4

[21] NCD Alliance, Invest to Protect.

[22] NCD Alliance, Invest to Protect.

[23] WHO, Saving Lives, Spending Less.

[24] Health Policy Partnership, Out Of The Ashes.

[25] OECD, Eurostat, and World Health Organization, A System of Health Accounts 2011: Revised edition (Paris: OECD Publishing, 2017), 234-239

[26] OECD and European Union, Health at a Glance: Europe 2022: State of Health in the EU Cycle (Paris: OECD Publishing, 2022)

[27] OECD and World Health Organization, Health at a Glance: Asia/Pacific 2022: Measuring Progress Towards Universal Health Coverage (Paris: OECD Publishing, 2022)

[28] NCD Alliance, Invest to Protect.

[29] Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, Financing Global Health 2020: The Impact of COVID-19, Seattle, Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, 2020, https://www.healthdata.org/policy-report/financing-global-health-2020-impact-covid-19

[30] Akashi, et al. “The role of the G20 economies in global health,” 11-15.

[31] World Health Organization, Noncommunicable Diseases Progress Monitor, Geneva, WHO, 2022, https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240047761

[32] Luke N. Allen, Simon Wigley, Hampus Holmer, and Pepita Barlow, “Non-communicable disease policy implementation from 2014 to 2021: a repeated cross-sectional analysis of global policy data for 194 countries,” The Lancet Global Health 11, no. 4 (April, 2023): e525-e533, https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(23)00042-6

[33] Allen, et al., “Non-communicable disease policy implementation,” e533.

[34] Jarnail Singh Thakur, Ria Nangia, and Sukriti Singh, “Progress and challenges in achieving noncommunicable diseases targets for the sustainable development goals.” FASEB bioAdvances 3, no. 8 (2021): 563-568. https://doi.org/10.1096/fba.2020-00117

[35] OECD, EU Country Cancer Profile: Italy 2023, EU Country Cancer Profiles, Paris, OECD, 2023 https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/social-issues-migration-health/eu-country-cancer-profile-italy-2023_a0a66c1d-en

[36] WHO, Saving Lives, Spending Less.

[37] Brenda Killen, “New NCD DAC Tracking Codes” (presentation, Global Dialogue on Partnerships for Sustainable Financing of NCD Prevention Control, Copenhagen, Denmark, April 9–11, 2018), 2018040918160901Ps24BrendaKillenSpeaker.pdf

[38] Abdillah Ahsan, Dwini Handayani, Krisna Puji Rahmayanti, and Nadira Amalia, “Earmarking Health Tax for Sustainable UHC Financing in G20 Developing Countries”, Berlin, The Global Solutions Initiative, 2022, https://www.global-solutions-initiative.org/policy_brief/earmarking-health-tax-for-sustainable-uhc-financing-in-g20-developing-countries/

[39] Access Health International, Strengthening Universal Health Coverage in Asia: Opportunities for Innovation in Private Health Insurance, Singapore, Access Health International, 2021, https://accessh.org/reports/strengthening-universal-health-coverage-in-asiaopportunities-for-innovation-in-private-health-insurance/

[40] NCD Alliance, Mobilising private investments to address the NCD funding gap, Geneva, NCD Alliance, 2022, https://ncdalliance.org/resources/mobilising-private-investments-to-address-the-ncd-funding-gap

[41] Claudio Jommi and Carlotta Galeone, “The Evaluation of Drug Innovativeness in Italy: Key Determinants and Internal Consistency.” PharmacoEconomics Open (2023): 373-381, https://doi.org/10.1007/s41669-023-00393-3

[42] Carlos Lula, “A brief story about the cancer fund experience” (presentation, Global Dialogue on Partnerships for Sustainable Financing of NCD Prevention Control, Copenhagen, Denmark, April 9–11, 2018), http://139.162.144.203:9002/090702_PlenarySession22/presentation/20180409181358CarlosLulaPs22Lula2Speaker.pdf

[43] Access Health International, Strengthening Universal Health Coverage in Asia.

[44] “Improving health finance cost efficiency” City Project, C/Can, last modified March 31,2023, https://citycancerchallenge.org/projects/improving-health-finance-cost-efficiency/

[45] Health Policy Partnership, Out of the Ashes.

[46] World Health Organization, World Health Statistics 2021: Monitoring for the SDGs, Geneva, WHO, 2021, https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/342703/9789240027053-eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

[47] Sustainable Finance Work Group, First Sustainable Finance Working Group Meeting: Presidency and Co-Chairs Note on Agenda Priorities, G20 Sustainable Finance Work Group, 2023, https://g20sfwg.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/SFWG-Presidency-and-Co-Chairs-Note-on-Agenda-Priorities.pdf

[48] Sustainable Finance Work Group, First Sustainable Finance Working Group Meeting.

[49] “Task Force-2: Our Common Digital Future: Affordable, Accessible and Inclusive Digital Public Infrastructure,” Task Force-2, last accessed July 10, 2023, https://t20ind.org/taskforce/our-common-digital-future-affordable-accessible-and-inclusive-digital-public-infrastructure/