Task Force 3: LiFE, Resilience, and Values for Well-being

Abstract

Sustainability and circularity of resource utilisation is crucial at a time when consumption patterns are contributing to environmental degradation and exacerbating social inequalities. The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly SDG 12, emphasise the importance of sustainable consumption and production. The G20 plays a critical role in promoting sustainability and has endorsed initiatives like the Circular Carbon Economy (CCE) and the LiFE (Lifestyle for Environment) framework. Integrating these frameworks can encourage sustainable consumption at the individual and societal levels. The G20 should support LiFE programmes, promote CCE practices, encourage circular business models, and foster sustainable behaviour especially by developing national action plans for sustainable consumption and production, and promoting cross-sectoral collaboration.

1. The Challenge

Sustainability and circularity of resource utilisation are becoming increasingly urgent amidst the heightening of environmental crises across the globe. The aim of sustainability is to find a balance between economic development, environmental protection, and social prosperity; circularity, meanwhile, speaks of keeping resources in use for as long as possible through closed-loop systems (McDonough and Braungart, 2002). Embracing these concepts can lead to a resilient, equitable, and prosperous future in which waste is minimised, resources are conserved, and human well-being is prioritised.

The current patterns of global consumption have become untenable and are leading to significant environmental and social challenges. Various studies and reports have highlighted the negative impacts of current consumption which include increased energy demand, resource depletion, environmental degradation, and rising carbon emissions.

Indeed, the need to manage consumption patterns for sustainable development has been recognised since the early 1970s. Reports like “Limits to Growth” in 1972 and the Brundtland Report in 1978, accompanied by the energy crisis of 1979, underscored the importance of addressing unsustainable consumption. International organisations such as the United Nations Environment Program and the United Nations Development Program have actively worked towards promoting sustainable consumption and production (SCP) since then.

The twelfth of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) adopted by the United Nations (UN) in 2015 focuses on sustainable consumption and production (SCP). This goal underlines the importance of making patterns of global consumption sustainable and calls for the implementation of the 10-Year Framework of Programmes on SCP Patterns (UNEP, 2023). SDG 12 consists of 11 targets covering policies, business practices, food, resource utilisation, waste management, and behaviour. Targets include the development and implementation of SCP policies, resource use monitoring, reduction of food loss and waste, proper management of hazardous waste, and waste reduction through recycling. Sustainability reporting by companies encourages the adoption of sustainable business practices, while sustainable public procurement policies aim to drive demand for sustainable products and services.

Awareness about sustainable development is promoted through the integration of global citizenship education[a] and education for sustainable development into national education policies and curricula. The adoption of environmentally sound technologies in developing countries and the implementation of standard accounting tools for sustainable tourism are important aspects of SDG 12.

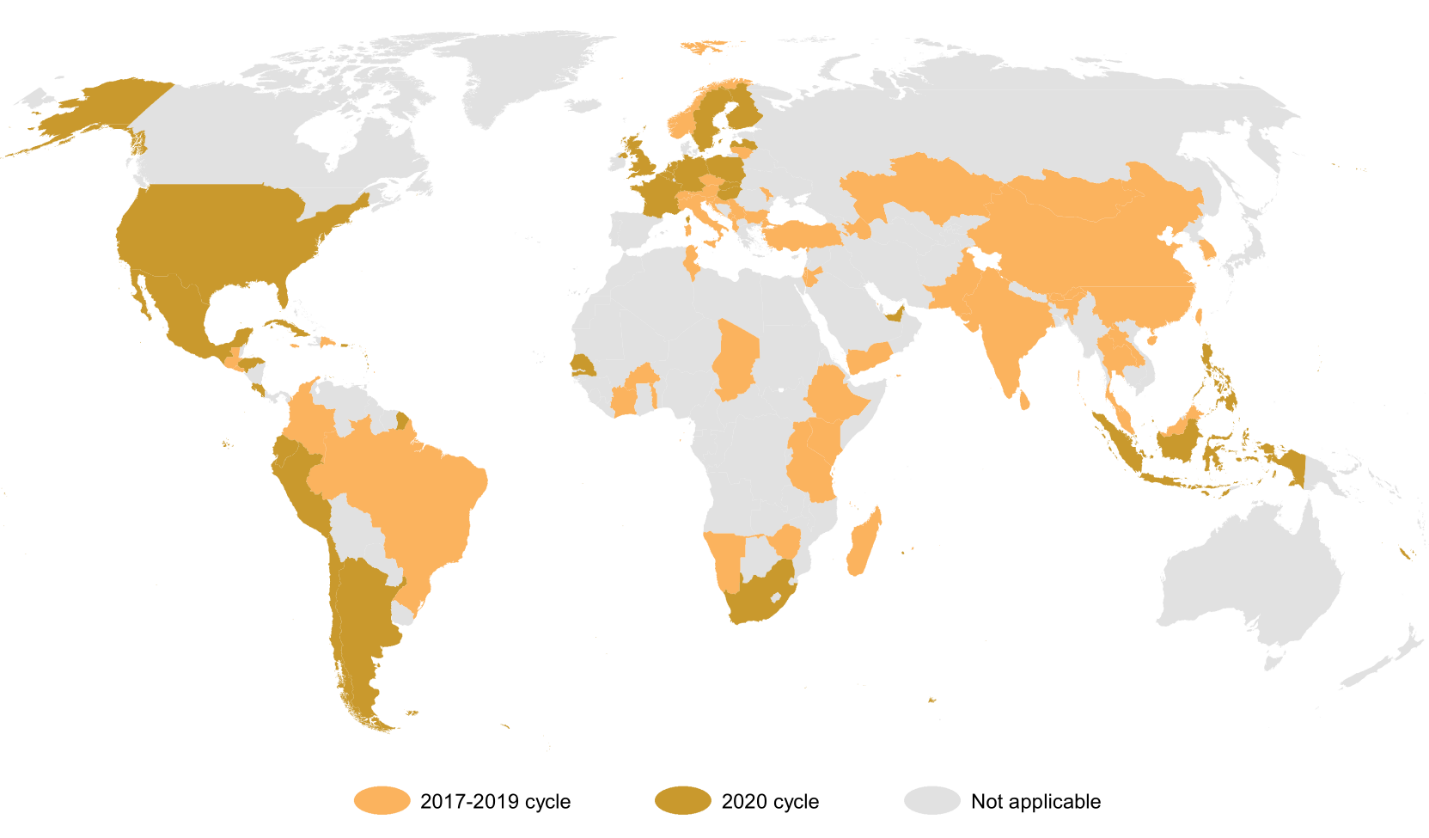

Despite the many actions taken towards addressing unsustainable patterns of consumption, the world is not on track to meet the various targets under SDG 12, including the development of a sustainable consumption and production national action plan (see Figure 1). Out of the 195 countries in the world, as of December 2020, 40 countries had reported on sustainable public procurement policies or action plans (UN Statistical Division, 2023). In this context, it is important to articulate unambiguously how the principle of common but differentiated responsibilities (CBDR) and respective capacities (RC) applies for distinguishing mitigation actions by developing countries from those by the developed world. While the latter is expected to lead the way, the former need to pursue sustainability without compromising economic development and social prosperity. This interpretation of the CBDR-RC needs to guide the formulation of a national SCP plan.

Figure 1. Sustainable Consumption and Production National Action Plans

Source: UN Statistical Division, 2023

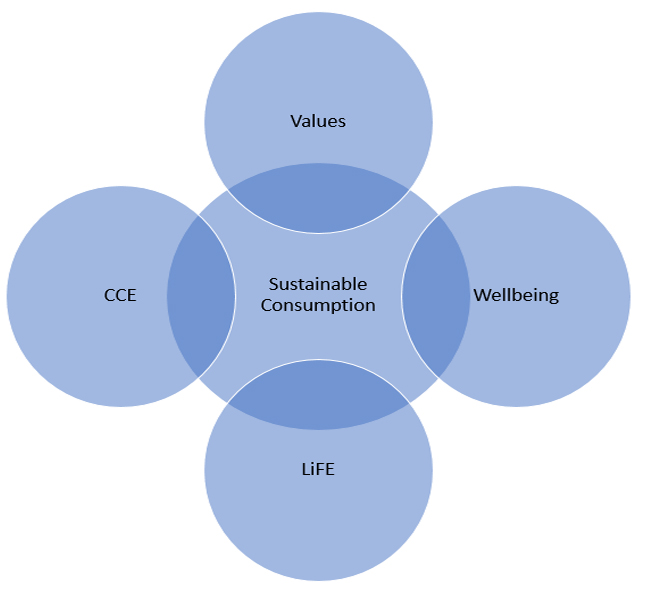

In aiming for sustainable consumption, there is merit in integrating existing frameworks developed by India’s T20 Task Force on ‘LiFE, Resilience, and Values for Well-being’, and building on relevant G20 commitments and efforts such as the Circular Carbon Economy (CCE) framework that seeks to alter individual behaviours and lifestyles for promoting sustainable consumption (see Figure 2). Pursuing sustainable consumption relies on individual choice which in turn reflects individual values and sense of well-being. The adoption of a CCE-based lifestyle at the individual level is a precursor to a collective shift towards more sustainable lifestyles.

Figure 2. Integrating CCE and LiFE Frameworks under T20 India Task Force 3

The G20-endorsed CCE framework emphasises the 4 Rs—reduce, reuse, recycle, and remove—which are essential in managing emissions. Although, until now, this framework has been applied at the national and international level, it can also be adopted at the individual level. The LiFE framework introduced at COP26 in 2021 by Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi, would entail changes in individual and societal behaviours involving greater uptake of sustainable consumption and production. The joint implementation of the CCE and LiFE frameworks is expected to contribute to achieving UN SDGs, particularly 4, 7, 11, 12, and 13. The integration of these frameworks can promote sustainable consumption, sustainable growth, and energy transition to achieve carbon circularity and carbon neutrality. The CCE framework can provide a roadmap for managing emissions at the individual, national, and international levels, while the LiFE framework can encourage a shift in individual and societal behaviours towards sustainable consumption and production. The latter espouses the principle of circular economy and nudges individuals to make sustainable choices by catalysing mass adoption of sustainable consumption.

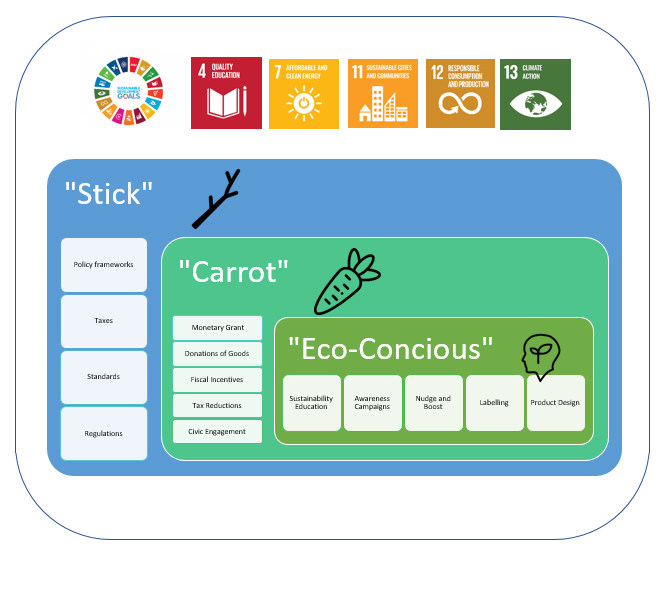

Figure 3. Policy Interventions to Promote Sustainable Consumption

Source: Author’s own

This brief proposes a range of policy interventions that governments can undertake to encourage sustainable consumption. Figure 3 illustrates the template of a strategy for integrating the CCE and LiFE frameworks.

“Eco-Conscious” interventions consist of implicit actions—such as sustainability education, awareness campaigns, nudges and boosts, labelling and product design—which involve a laissez-faire approach, and act on individual values and the individual sense of well-being to prompt more informed sustainable choices.

“Carrot” interventions represent explicit attempts which are more persuasive than eco-conscious interventions at encouraging more sustainable choices. These interventions include monetary and fiscal incentives, goods donations, tax reductions, and opportunities for civic engagement.

“Stick” interventions involve the most aggressive form of persuasive action for encouraging sustainable choices. These interventions include policy formulation, taxation, and imposition of standards and regulations that deter unsustainable choices by penalising them.

Action for effecting systemic changes besides those that can be achieved by the above-mentioned interventions include product design that allows reuse and recycling, closed-loop supply chains, collaborative consumption, and ‘product-as-a-service’[b] and ‘waste-to-resource’ initiatives.[c]

‘Nudging’ aims at encouraging sustainable consumption by making sustainable options more accessible, attractive, and convenient. It recognises that promoting sustainable consumption and production requires the active participation of individuals and the society as a whole. According to behavioural sciences such as psychology and behavioral economics, individual behaviour is not always rational and can be influenced by biases and heuristics. Formulating policies that are effective ‘nudges’ for behavioural change requires accounting for differences in behaviour explained by these biases and heuristics (Thaler and Sunstein, 2008). Nudges such as default options and those involving simplification of complex information have been incorporated in policies that ensure consumer protection and regulate competition (Thaler and Sunstein, 2008). Nudges can be leveraged for inducing sustainable consumption across sectors such as housing, transport, and food & beverage, which have significant environmental impacts (Thøgersen, 2012).

2. The G20’s Role

The G20 accounts for approximately 75 percent of global GDP, 80 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions and 60 percent of the world’s population, and plays a critical role in accelerating energy transition and meeting collective climate targets. These countries are also responsible for a significant portion of the world’s waste production and ecological footprint. For instance, the United States is responsible for 16.4 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions despite being home to just 4.4 percent of the world’s population (EPA, 2021). The average American consumed more than double the global average of natural resources in 2017 (WWF, 2017), and generated the largest amount of per capita electronic waste in 2021 (Statista, 2021). The G20 countries contribute significantly to both plastic and electronic waste; among them, the United States, China, and Japan top the list of contributors to plastic waste (Jambeck et al., 2015; Baldé et al., 2017).

The G20 countries have implemented several initiatives for promoting sustainable consumption. For instance, Germany launched a national initiative called “Green Button” to promote sustainable fashion and provide information on sustainable textile production, while France introduced a law to reduce generation of food waste by prohibiting supermarkets from throwing away unsold food (WRI, 2022). Japan introduced a “Cool Biz” campaign that seeks to reduce energy consumption by encouraging employees to dress lightly in the summer months (UNEP, 2017). The G20 also adopted the Action Plan on the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development which calls for the promotion of sustainable consumption and production patterns (WRI, 2022).

Table 1 G20 Commitments and Actions on Climate Change and Sustainable Consumption

| G20 2017 | G20 2018 | G20 2019 | G20 2020 | G20 2021 | G20 2022 |

| “We remain collectively committed to mitigate greenhouse gas emissions through, among others, … energy efficiency, …”

“We launch .. The G20 Resource Efficiency Dialogue … to promote sustainable consumption and production patterns.” |

“We will increase … to enhance … efficiency, … reduce food loss and waste”

“we encourage… cooperation in energy efficiency“ |

“We recognize that improving resource efficiency through … circular economy, sustainable materials management, the 3Rs (reduce, reuse, recycle) and waste to value, … We look forward to the development of a roadmap of the G20 Resource Efficiency Dialogue. “ | “We endorse the Circular Carbon Economy (CCE) Platform, with its 4Rs framework (Reduce, Reuse, Recycle and Remove)“ | “we will accelerate our actions across mitigation, adaptation and finance, … taking into account different approaches, including the Circular Carbon Economy,…” | “We recognize the importance of a sustainable, resilient, inclusive, and just recovery

… including the circular carbon economy.”

“We acknowledge, …including environmentally conscious lifestyle“ |

Source: G20 Communiqués

India’s T20 task force, ‘LiFE, Resilience & Values for Wellbeing‘ aims at contributing to global climate governance by introducing climate mitigation strategies at the individual level. This policy brief proposes to build on existing efforts and conclusive agreements by the G20 for effectively pushing this agenda forward.

The G20 has been consistent in reiterating its commitment to addressing climate change and promoting sustainability at its annual summits:

- In 2017, the G20 emphasised the need for prioritising innovation in the domains of energy efficiency, and sustainable and clean energies. The G20 countries also launched the G20 Resource Efficiency Dialogue to facilitate exchange of good practices, and promote sustainable consumption and production patterns.

- In 2018, the G20 focused on the importance of engaging with the private sector and the scientific community to enhance productivity, efficiency and sustainability in the agro-food global value chains.

- In 2019, the G20 highlighted the significance of practices that promote resource efficiency and sustainable materials management, including waste management and circular economy–based practices. They also expressed support for recycled products and measures for increasing their demand.

- In 2020, the G20 endorsed the CCE Platform for reducing emissions and promoting economic growth based on holistic and integrated approaches in various sectors such as energy, industry, mobility, and food.

- In 2021, the G20 addressed the need for long-term strategies -based on approaches such as the CCE- that align with achieving a balance between emissions and removals by mid-century.

- In 2022, the G20 countries recognised the need for a sustainable, resilient, inclusive and just recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic. They also acknowledged the importance of implementing approaches such as the CCE that accelerate the transition to a net-zero future and achieve the targets implied by nationally determined contributions (NDC) in a manner that accounts for differences in national circumstances. The G20 also highlighted the significance of the role played by subnational governments in addressing climate change. The G20 also put into perspective the urgency of adopting environmentally conscious lifestyles.

Overall, the G20’s statements and commitments reflect a growing recognition of the need for sustainability, resource efficiency, and an unwavering focus on climate action. The consistent endorsement of the CCE and the priority accorded to long-term strategies underline G20’s commitment to a comprehensive and integrated approach to climate action.

3. Recommendations to the G20

Building on G20’s prior commitments and climate action, and in the spirit of the UN Marrakech Process on Sustainable Consumption and Production, this policy brief makes the following recommendations to G20 governments for boosting sustainable consumption:

- Provide technical and financial support to LiFE programmes in the Global South for promoting practices that enable sustainable consumption and production in a way that honours the principle of CBDR-RC. For example, retrofitting of smart meters onto traditional meters can help raise awareness about energy consumption.

- Promote CCE practices in the Global South by encouraging closed-loop systems and minimising carbon emissions. This can be achieved by implementing policies that prioritise resource efficiency, waste reduction, and product life extension. Moreover, policies that incentivise businesses to adopt circular practices can also be designed. As prescribed in the Paris Agreement, technology transfer and capacity building need to accompany the disbursement of climate finance to developing countries.

- Encourage circular business models that prioritise resource efficiency, waste reduction, and product life extension, by leveraging policy instruments such as tax credits, subsidies, and public procurement.

- Promote sustainable behaviour among consumers by disseminating information, imparting education, and nudging for responsible consumption. Policymakers can implement awareness campaigns, labeling schemes, and public outreach initiatives for these purposes.

- Foster cross-sectoral collaboration among governments, businesses, civil society and academia to promote sustainability, circularity in resource use, and carbon neutrality. This can be achieved through public-private partnerships, policy frameworks anchored in cross-sectoral interaction, and international cooperation for climate action.

- Institute a national action plan for sustainable consumption and production as part of a country’s NDC. Countries can be encouraged to submit their national frameworks for sustainable consumption and production as part of their NDCs. This will enable them to outline specific strategies, policies, and measures that promote sustainable consumption patterns and environment-friendly production methods. These frameworks can include initiatives such as resource efficiency, waste management, sustainable sourcing, and promoting circular carbon economy principles and technologies.

Attribution: Noura Y. Mansouri, “Integrating the Circular Carbon Economy and LiFE Frameworks to Promote Sustainable Consumption,” T20 Policy Brief, June 2023.

Bibliography

Baldé, Cornelis Peter, Vanessa Forti, Pam Scott, and Faye Ducharme. 2017. “The Global E-waste Monitor 2017.” United Nations University, International Telecommunication Union, and International Solid Waste Association. https://collections.unu.edu/eserv/UNU:6346/Global-E-waste_Monitor_2017_En.pdf.

EPA. “EPA Releases 2021 Data Collected Under Greenhouse Gas Reporting Program.” Accessed September 2021. https://www.epa.gov/newsreleases/epa-releases-2021-data-collected-under-greenhouse-gas-reporting-program.

International Monetary Fund. (2022). World Economic Outlook Database. Retrieved from https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/weo-database/2022/October

Jambeck, Jenna R., Roland Geyer, Chris Wilcox, Theodore R. Siegler, Miriam Perryman, Anthony Andrady, Ramani Narayan, and Kara Lavender Law. 2015. “Plastic Waste Inputs from Land into the Ocean.” Science 347 (6223): 768–71. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1260352.

McDonough, William, and Michael Braungart. Cradle to Cradle: Remaking the Way We Make Things. New York: North Point Press, 2002.

OECD. 2021. “Towards a more resource-efficient and circular economy: The role of the G20.” Accessed June 7, 2023. https://www.oecd.org/environment/waste/OECD-G20-Towards-a-more-Resource-Efficient-and-Circular-Economy.pdf.

Reisch, L. A., & Sunstein, C. R. (2016). Do Europeans like nudges? Journal of Consumer Policy, 39(4), 365-392.

“Statista – The Statistics Portal.” 2021. https://www.statista.com.

Thaler, R. H., & Sunstein, C. R. (2008). Nudge: Improving decisions about health, wealth, and happiness. Yale University Press.

Thøgersen, J. (2012). A socio-psychological perspective on behaviour change interventions: The importance of context, acceptability and implementation. In G. L. Lowe & S. J. Smith (Eds.), Advances in social psychology and environmental sustainability (pp. 101-120). Psychology Press.

UN Statistical Division (2023), Our World in Data, Sustainable Consumption and Production National Plan in the World, Access Date: June 08, 2023

UNEP. 2023. “10YFP – 10 Year Framework of Programmes on Sustainable Consumption and Production Patterns” https://www.unep.org/explore-topics/resource-efficiency/what-we-do/one-planet-network/10yfp-10-year-framework-programmes

UNESCO. 2023. “What is global citizenship education?” https://en.unesco.org/themes/gced/definition

United Nations. (2023). World Population Prospects 2022. Retrieved from https://population.un.org/wpp/

World Resources Institute. (2022). CAIT Climate Data Explorer. Retrieved from https://www.climatewatchdata.org/

WWF. (2017). Living planet report 2018: Aiming higher. Retrieved from https://www.worldwildlife.org/pages/living-planet-report-2018-aiming-higher

Endnote

[a] Global Citizenship Education (GCED) aims to empower learners of all ages to assume active roles, both locally and globally, in building more peaceful, tolerant, inclusive and secure societies (UNESCO, 2023).

[b] The adoption of a Product-as-a-Service model, which fundamentally redefines the approach towards goods and services, has the potential to introduce sustainable practices in product management.

[c] The “Waste to Resource” initiative involves the collective participation of numerous companies and organizations within the waste management sector. Its primary objective is to minimize landfill waste by transforming it into valuable resources through repurposing techniques.