Task Force 7: Towards Reformed Multilateralism: Transforming Global Institutions and Frameworks

Abstract

The IMF and the World Bank constitute key components of the global governance architecture developed after the Second World War. As the world has become multipolar, however, the Bretton Woods Institutions (BWI) have largely failed to adapt their policies and organisational structures. The lack of influence in established governance institutions by non-Western economies has contributed to a sense of marginalisation and driven the increasing focus on developing parallel multilateral development banks (MDBs) that diffuse alternative norms and present alternatives to the BWI. While parallel MDBs can produce net benefits, their relative novelty and potential competition with the BWI also creates regulatory and operational challenges. This Policy Brief argues that the G20 must follow a two-track approach that pursues both reform of the BWI and coordination between the BWI and parallel MDBs to maximise positive development outcomes and reduce potential tensions.

1. Introduction

Today, multilateral global governance institutions face a variety of challenges including heightened geopolitical and trade tensions, continued nuclear proliferation, growing global economic inequality, and the climate crisis. Following the United States’s ‘unipolar moment’, the twenty-first century has been defined by the political and economic rise of Asian economies, especially India and China, and the shift to a multipolar global order. The growing influence of non-Western countries has resulted in the questioning of the transatlantic power structure of the global governance architecture beginning in 1945.[1] Contestations toward the present architecture have included ever more demands to reform key governance bodies such as the Bretton Woods Institutions (BWI), the International Monetary Fund (IMF), and the World Bank Group (WBG) “to overcome standstill or sub-optimal functioning.”[2] Protracted reform, insufficient involvement of developing economies, and growing multipolarity heighten the risk of ‘institutional drift’ for established institutions: an institution’s “real role will change and its effectiveness may erode” if it “fails to change in tandem with a changing environment.”[3]

This Policy Brief discusses the opportunities and challenges linked with the rise of parallel institutions (PIs) as alternatives to the IMF and the WBG, specifically focusing on the role of multilateral development banks (MDBs). The IMF and WBG have been criticised for policy shortcomings, inadequately reflecting contemporary power distributions in their organisational structure, and their limited internal reform. This has led to the emergence of parallel MDBs as alternative governance bodies. While this can produce net developmental benefits, the G20 must emphasise the integration of MDBs as responsible governance stakeholders while supporting and facilitating reform of the BWI.

2. The Challenge

The IMF’s policy prescriptions imply long-standing structural issues. IMF programs aim to restore access to capital markets through liberalising capital accounts and implementing austerity measures such as tax hikes and subsidy cuts. These policies frequently exacerbate socio-economic inequality and instability in recipient countries, amplifying social tensions.[4] Many recipient countries also eventually return to IMF programs, casting doubts on the effectiveness of IMF policies in facilitating long-term macroeconomic stability.[5] These policy failures have negatively affected the IMF’s legitimacy in developing economies, reducing their contribution to the IMF’s reserves.[6] This has contributed to a general capitalisation issue that limits the IMF’s ability to effectively respond to global financing needs.[7]

The WBG has also been the target of criticism. Since the 2007-2008 global financial crisis (GFC), the WBG has largely failed to significantly contribute to growth and development in emerging economies, partially due to the risk-averse use of its capital base,[8] which is contrasted by the more liberal use of capital in mechanisms such as the Belt-and-Road Initiativ.[9] There have also been perceptions of WBG policy as ignoring local conditions while producing detrimental negative social and environmental effects for host communities.[10] The WBG’s mostly neoliberal policy prescriptions are also often viewed as exacerbating social inequalities and environmental damage.[11]

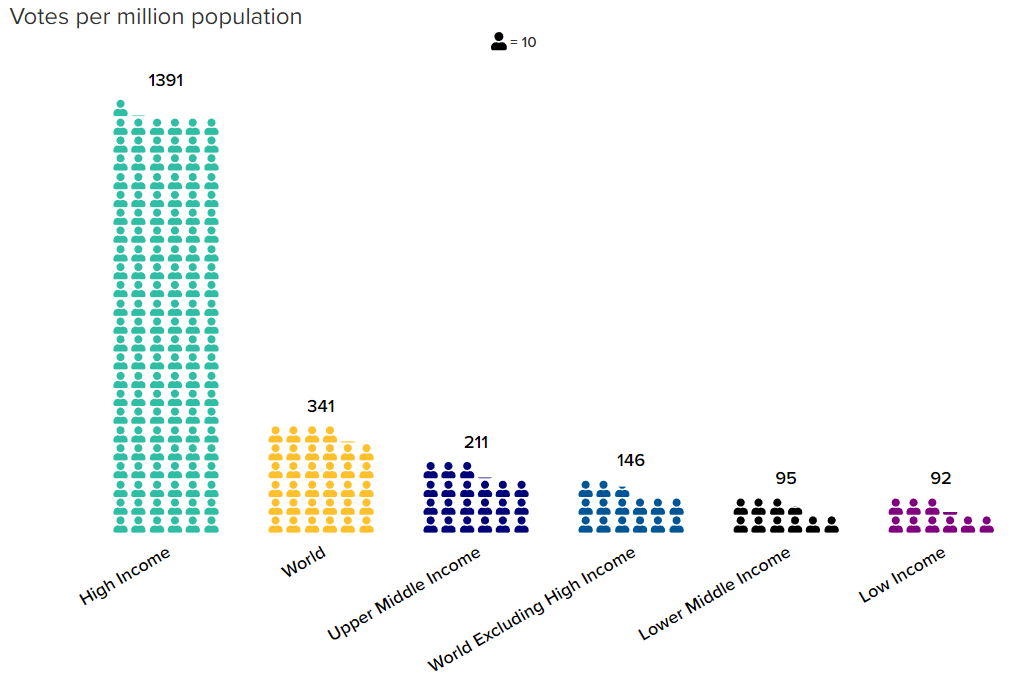

The BWI now also operate in an increasingly multipolar system. The share of emerging markets in the global population, capital stock, trade, and GDP has risen significantly since the end of the Second World War.[12] The formation of the G20 in 1999 reflects this “new world created since the 1970s by globalised economic growth.”[13] The organisational structure of the BWI, however, fails to reflect these shifts. Non-Western economies are mostly underrepresented in decision-making processes, whereas high-income economies, primarily in Western Europe and North America, have significantly higher representation in the WBG (see Figure 1).[14]

Figure 1: Global Representation at the WBG Across Income Levels in Votes Per Million Population (2020)

Source: Atlantic Council

Despite voting reforms in 2008/2009, Western European countries and key US allies continue to hold more than 70 percent of the total voting power in the BWI.[15] The United States exercises a de facto voting power over IMF policy.[16] The lack of non-Western representation is epitomised in the top management positions of the WBG and IMF always being held by a European or American, respectively. As such, the structure and policymaking of the BWI “reflects the preferences and social purposes prevalent” among Western elites.[17] Crucially, macroeconomic policy is not primarily shaped by countries that require financial assistance, contributing to the disconnect between BWI policy and local needs.

Reform initiatives have suffered from severe protraction. The 2008/2009 voting reforms maintained a largely peripheral role for emerging economies and did little to change the perception of the IMF as being an essentially US-led institution that represents Western political preferences and development models.[18] This perspective is heavily shaped by any change in the IMF vote quota being contingent on approval by the US Congress, which Congress has thus far refused to agree to.[19] Negotiations and debates surrounding reform have consequently been protracted and open-ended, limiting the confidence that the BWI can meaningfully reform itself.[20] As the world becomes multipolar, the BWI have come to experience institutional drift.

3. The G20’s Role

The lack of reform in the BWI has led to the growth of parallel MDBs. PIs “perform a function similar to those [institutions] that already exist” and “help to create and diffuse new norms.”[21] Parallel MDBs include the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) and the BRICS-linked New Development Bank (NDB). The voting procedure in the NDB, where each country has the same voting share and no country holds unilateral veto powers, epitomises the diffusion of new norms and processes.[22] This diffusion also extends to the policy prescriptions pursued by rising powers. India and China, for instance, have pragmatically intervened in their economies to ensure stability and growth while maintaining a key role for state-owned and state-linked enterprises, challenging the more neoliberal model of the BWI.[23] Further, MDBs can provide additional sources of funding, introduce alternative ways for managing development finances, and grant non-Western actors more influence in decision-making processes. For countries that have been largely excluded from global governance processes, this presents a highly enticing prospect.

The emergence of parallel MDBs creates various governance opportunities. The discussed provision of additional development financing on more flexible terms can bolster regional and global governance while promoting economic development. The distinctly regional focus of MDBs such as the AIIB also means that policies can be geared more towards idiosyncratic regional needs and concerns. Western, mostly neoliberal conceptualisations of ‘development’ can be challenged by “a new [and institutionalised] pluralism of ideas for economic development.”[24] The subsequent appeal of MDBs increases the reform pressure on the BWI while filling some of the gaps in existing governance architecture. The growing economic importance of non-Western economies and the institutionalisation of this shift, such as in the form of BRICS, make it likely that parallel MDBs will play a key governance role going forward.

Yet, parallel MDBs also create regulatory challenges. PIs fragment the global governance architecture and potentially compete with existing institutions for projects and influence, diminishing the returns of investments. The capitalisation of MDBs such as the AIIB and NDB is still significantly lower than that of the BWI,[25] making these institutions less capable of responding to global crises. Operationally, their relative novelty can create underdeveloped transparency regulations, leading to potentially unsustainable and unregulated financing practices that can facilitate greater economic exposure and corrupt practices.[26] Inter-state relations between non-Western powers can also complicate governance: for instance, how will Indian-Sino tensions shape the effectiveness of BRICS and the NDB? Furthermore, parallel MDBs can also be shaped by unilateral action. For example, how does China shape the AIIB funding policy, given that it provides most of the AIIB’s capital base and holds more votes than any other country?[27] While somewhat balancing the global playing field, the de facto degree of control possessed by some countries in certain PIs also creates the risk of PIs not necessarily being more equitable than existing institutions.

The emergence of parallel MDBs—a reaction to institutional drift—ultimately creates both developmental opportunities and regulatory challenges. While parallel MDBs do not inherently challenge the institutional existence of the BWI, the management of the relationship between the BWI and MDBs must be a policy priority for the G20.

The diversity of its membership makes the G20 uniquely placed to respond to the regulatory challenge of managing the future of the BWI and parallel MDBs. While the development opportunities generated by parallel MDBs are too significant to discount, efforts to reform the BWI and improve their functioning should not be abandoned. For the moment, the BWI constitutes the only organisations that are capable of responding to financial crises and financing needs on a truly global scale and are therefore likely to remain important. In practice, the G20 must lead the drive for BWI reform while integrating parallel MDBs into the global governance architecture in a way that maximises their developmental output, maintains and ensures their multilateralism, and improves their internal governance to ensure regulatory and financial sustainability and accountability. The G20’s policy should thus focus on a two-track approach: one track focused on reforming the BWI and the other focused on enhancing the role of emerging MDBs as responsible governance stakeholders that can work effectively alongside the BWI.

4. Recommendations to the G20

Policies for BWI Reform

While MDBs are gaining importance, the BWI constitute the bodies with the highest capitalisation, making them the most capable of addressing global financial and economic challenges. Policies must focus on enhancing the BWI’s functioning and policies rather than eroding the role of the BWI. The following measures would help accomplish this:

- The G20 must act as a platform where reforms of BWI governance structures can be discussed and facilitated, especially in terms of improving the influence of developing economies and enhancing diversity in leadership positions. There are limitations to this, most notably the United States’s de facto veto. Yet, the 2008-2009 IMF reforms have also indicated that there is space for (some) reform. This must be pursued further to promote BWI legitimacy, especially in developing economies.

- The G20 must also seek to promote alternative policies of responding to economic crises. The austerity-focused policy emphasis of the IMF and the risk-aversiveness of the WBG has significantly harmed global support for the BWI. There must be renewed effort to develop policy responses that ensure fiscal accountability and sustainability while protecting the most vulnerable segments of the populations of recipient countries. A greater say of non-Western voices and a subsequent promotion of alternative development models could be one pathway. Additionally, the IMF should make more proactive use of its Special Drawing Rights to prevent growing fiscal exposure while the WBG must be more willing to respond to specific local needs and conditions.

- The WBG should enhance its coordination with other organisational stakeholders that play a crucial role in structuring development finance. Improved coordination with the OECD, for instance, could help reshape the flow of development funds from OECD countries in a way that is consistent with the development objectives formulated by the G20 and other relevant international organisations.

- The G20 must strengthen the role of non-state actors in development capitalisation and policymaking. The contemporary structure of the BWI prevents non-state actors from playing a more active role in shaping policy outcomes and mobilising capital.[28] A greater integration of non-state actors could be achieved through the WBG putting a greater emphasis on promoting public-private partnerships and involving NGOs and corporations in the planning and development of projects to a greater degree.

- The G20 must also increase the funding for sustainable infrastructure, climate change resilience, and renewable energies. Both the IMF and WBG have been criticised for their focus on debt repayments over the financing of climate change mitigation measures.[29] The acute nature of the climate crisis, especially in developing economies, however, means that sustainable solutions must be financed as soon as possible. As such, reshaping lending and repayment policies in a way that serves the developmental and crisis response needs of these countries should be made the top financing responsibility.

Policies for Parallel MDB Integration

Besides improving the political legitimacy of the BWI, the G20 must develop and implement policies that ensure coordination between the BWI and MDBs to promote greater sustainability and inclusivity in global governance mechanisms. The following steps would help address this:

- The G20 must function as the primary platform for dialogue and consultation between the BWI and MDBs and their state backers. Discussions should focus on delineating respective mandates, financing priorities, and governance structures. This can contribute to reducing tensions and building trust.

- The G20 must encourage greater coordination between existing and emerging global governance institution through the development of mechanisms for sharing activities, coordinating loan and grant activities, and creating a structure in which the BWI and MDBs can address global challenges in tandem rather than in competition. This can reduce potential tensions between institutions and their backers, facilitating the maximisation of development outcomes and reducing governance fragmentation.

- The G20 should promote best practices in governance, transparency, and accountability in parallel MDBs. As discussed, this is particularly crucial in relatively novel organisations that may lack the organisational infrastructure to ensure adequate financial governance. Best practices could focus on the development of standards for lending, risk management, project evaluation, transparency in decision-making and reporting, and accounting practices. A creation of specific G20 work groups/committees also involving representatives of the BWI and MDBs could create an institutional framework for this.

- The G20 could also support operational capacity-building efforts in MDBs, such as through the provision of technical assistance, training, and other forms of assistance that ensure that projects and investments are implemented in a socially and environmentally sustainable way that includes input from host communities.

- As with the BWI, the G20 must promote the participation of the private sector and non-state actors in capital mobilisation and decision-making processes in MDBs. This could include the expansion of mechanisms for co-financing and public-private partnerships, especially with private sector activities in developing economies and in projects focused on promoting sustainable infrastructure investment.

- The G20 can also play a key role in MDB investments contributing to the joint pursuit of a more responsible environmental and social avenue for development. This could include an investment focus on projects that comply with the SDGs, such as through mechanisms that prioritise investments in areas such as climate change mitigation, enhancing food security, reducing inequality, promoting sustainable infrastructure, and funding renewables. Despite the parallel nature of MDBs, this could create synergies with existing global governance institutions.

4. Conclusion

The emergence of parallel MDBs challenges the traditional role of the BWI in the post-Second World War order. Parallel institutions have emerged both due to the rise of states that were and are largely marginalised in the global governance arena and the unwillingness and inability of the BWI to engage in meaningful structural reform. The emergence of parallel MDBs has added a layer of complexity to global governance and reflects slow but steady shifts in political and economic power, especially towards Asia. Yet, global governance is changing rather than unravelling. The BWI will remain relevant because of their financial size and experience managing global crises. For the G20, these shifts mean that the grouping must work towards both the reform of the BWI as well as the integration of parallel MDBs and institutions to maximise developmental gains and reduce geopolitical tensions.

Attribution: Aaron Magunna, “Institutional Drift: Multipolarity, Bretton Woods, and Parallel Multilateral Development Banks,” T20 Policy Brief, June 2023.

[1]Alexander Cooley and Daniel Nexon, Exit from Hegemony: The Unraveling of the American Global Order (New York: Oxford University Press, 2020).

[2]Giampiero Massolo, “Global Governance for Global Challenges,” Italian Institute for International Political Studies, 2021, https://www.ispionline.it/en/publication/global-governance-global-challenges-30779.

[3] Matthew D. Stephen, “Emerging Powers and Emerging Trends in Global Governance,” Global Governance 23, no. 3 (2017): 483-502, https://doi.org/10.1163/19426720-02303009.

[4] Rebecca Ray, “IMF Austerity is Alive and Increasing Poverty and Inequality,” Global Development Policy Center, 2021, https://www.bu.edu/gdp/2021/04/05/imf-austerity-is-alive-and-impacting-poverty-and-inequality/.

[5] Ajay Chhibber, “Modernizing the Bretton Woods Institutions for the Twenty-First Century,” Atlantic Council, 2022, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/Modernizing-and-Revamping-the-Bretton-Woods-Institutions-for-the-Twenty-First-Century.pdf.

[6] Ngaire Woods, “Global Governance after the Financial Crisis: A New Multilateralism or the Last Gasp of the Great Powers?” Global Policy 1, no. 1 (2010): 52-53, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1758-5899.2009.0013.x.

[7] Chhibber, “Modernizing the Bretton Woods Institutions for the Twenty-First Century,” 12.

[8] Chhibber, “Modernizing the Bretton Woods Institutions for the Twenty-First Century,” 5-7.

[9] Elizabeth C. Losos and T. Robert Fetter, “Building Bridges? PGII versus BRI,” Brookings Institution, 2022, https://www.brookings.edu/blog/future-development/2022/09/29/building-bridges-pgii-versus-bri/.

[10] Sasha Chavkin et al., “How the World Bank Broke its Promise to Protect the Poor,” Huffington Post, 2015, https://projects.huffingtonpost.com/worldbank-evicted-abandoned

[11] Sarah Babb and Alexander Kentikelenis, “International Financial Institutions as Agents of Neoliberalism,” In The SAGE Handbook of Neoliberalism, eds. Damien Cahill et al. (London: Sage), 22.

[12] Amin Mohseni-Cheraghlou, “Economic and Financial Multilateralism in Disarray,” Atlantic Council, 2022, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/econographics/economic-and-financial-multilateralism-in-disarray/.

[13] Adam Tooze, 2019, Crashed: How a Decade of Financial Crisis Changed the World (London: Penguin).

[14] Amid Mohseni-Cheraghlou, “The North-South Divide is growing. Can a new Bretton Woods help?,” Atlantic Council, 2022, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/econographics/the-north-south-divide-is-growing-can-a-new-bretton-woods-help/.

[15] Amin Mohseni-Cheraghlou, “Democratic Challenges at Bretton Woods Institutions,” Atlantic Council, 2022, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/econographics/inequality-at-the-top-democratic-challenges-at-bretton-woods-institutions/.

[16] Stephen, “Emerging Powers and Emerging Trends in Global Governance,” 492.

[17] Stephen, “Emerging Powers and Emerging Trends in Global Governance,” 487.

[18] Woods, “Global Governance after the Financial Crisis,” 56.

[19] Jakob Vestergaard and Robert H. Wade, “Trapped in History – The IMF and the US Veto,” Danish Institute for International Studies, 2015, https://pure.diis.dk/ws/files/118786/pb_imf_and_the_us_veto.pdf.

[20] Stephen, “Emerging Powers and Emerging Trends in Global Governance,” 494.

[21] James F. Paradise, “The Role of “Parallel Institutions” in China’s Growing Participation in Global Economic Governance,” Journal of Chinese Political Science 21 (2016): 150, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11366-016-9401-7.

[22] Mohseni-Cheraghlou, “Democratic Challenges at Bretton Woods Institutions”

[23] Stephen, “Emerging Powers and Emerging Trends in Global Governance,” 493.

[24] Stephen, “Emerging Powers and Emerging Trends in Global Governance,” 493.

[25] Molly Elgin-Cossart and Melanie Hart, “China’s New International Financing Institutions,” Center for American Progress, 2015, https://www.americanprogress.org/article/chinas-new-international-financing-institutions/.

[26] Matthew Jenkins, “Multilateral Development Banks’ Integrity Management Systems,” U4 Anti-Corruption Resource Centre, 2016, https://www.u4.no/publications/multilateral-development-banks-integrity-management-systems-2.pdf.

[27] AIIB, “Members and Prospective Members of the Bank,” https://www.aiib.org/en/about-aiib/governance/members-of-bank/index.html.

[28] Nisha Narayanan, “Changing Bretton Woods: How Non-State and Quasi-State Actors Can Help Drive the Global Development Agenda,” Atlantic Council, 2022, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/in-depth-research-reports/report/changing-bretton-woods-institutions-how-non-state-and-quasi-state-actors-can-help-drive-the-global-development-agenda/.

[29] Nicola Limodio, “Tackling Climate Change Will Require Reforming the World Bank and IMF – Here are Two Options,” The Conversation, 2022, https://theconversation.com/tackling-climate-change-will-require-reforming-the-world-bank-and-imf-here-are-two-options-194757.