Task Force 6: Accelerating SDGs: Exploring New Pathways to the 2030 Agenda

In 2014, recognising the criticality of bringing women into the workforce, G20 leaders committed to reducing the gender gap in labour force participation by 25 percent in member countries by 2025. While significant progress has been made since, accelerated progress is needed in the next two years. Outcomes-based financing (OBF), including impact bonds, has recently emerged as a promising solution to address this issue. This Policy Brief draws on evidence and learnings from relevant OBF projects to recommend that the G20: (i) encourage the adoption of OBF principles (clearly defined outcomes, rigorous and independent verification, payments linked to outcomes, risk transfer when relevant, robust performance management, outcome-based budgeting, and strong governance and accountability) in female labour force participation schemes/programmes; (ii) create a cross-sector task force to leverage the strengths of various engagement groups; and (iii) encourage member states to create an ecosystem conducive to OBF.

1. The Challenge

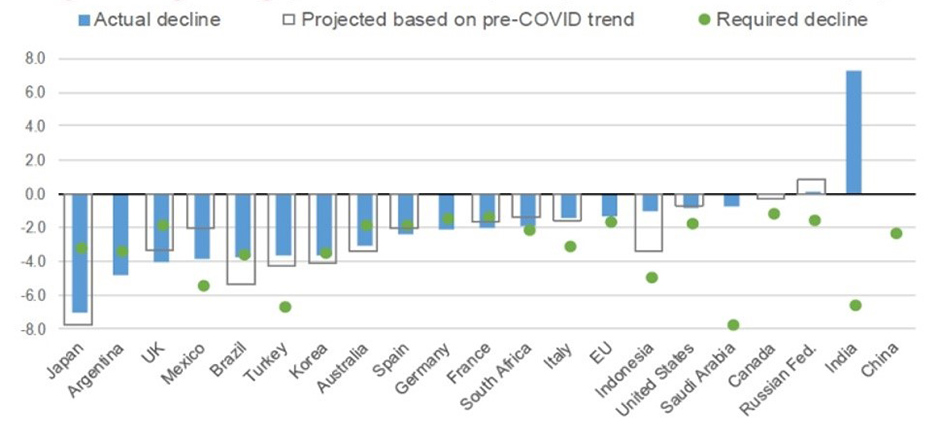

There is a positive ripple effect when women work and earn income—the gains accrue directly to the women, and get transferred to their children and households, and eventually make their way to a country’s economy and GDP. In 2014, recognising the criticality of bringing more women into the workforce, especially as it relates to the achievement of the 2030 Agenda, G20 leaders committed to reducing the gender gap in labour force participation by 25 percent in member countries by 2025 (the ‘25×25’ goal) (OECD, 2015). With just two years remaining before the deadline, many G20 members have made significant progress, showing a steady decline in the gender gap in labour force participation despite global setbacks caused by COVID-19, the Ukraine crisis, global inflation, and other external shocks (OECD, 2021). However, there is still a long way to go. In certain member countries, such as India, female labour force participation continues to be low and could further decline (OECD, 2021).

Figure 1: Change in the Gender Gap in Labour Force Participation Rate (2012-2020)

Source: ILO via OECD calculations based on national labour force surveys and census data for China

Women’s decision and ability to participate in the labour force is driven by a complex web of economic, social, and cultural factors, which interact at both household and macro levels (ILO, 2014). Based on global evidence, some of the most important drivers include educational and skill attainment, fertility rates and the age of marriage, economic growth/cyclical effects, and urbanisation. In addition to these issues, social norms determining the role of women in the public domain continue to affect outcomes.

Substantial amounts of public and private investment are channelled to augmenting employability and skill attainment for youth, including women. For example, in India, government schemes, such as the Pradhan Mantri Kaushal Vikas Yojana (PMKVY), had an average budget of approximately US$1450 million for the period 2016-2020 (Ministry of Skill Development and Entrepreneurship, 2023). Private capital has also been mobilised to invest in this area, with the cumulative corporate social responsibility (CSR) expenditure amounting to around US$500 million over 2014-15 to 2020-21 (Ministry of Corporate Affairs, 2021).

However, a large share of this funding is still predominantly input-driven (for example, enrolling a certain number of trainees in a skilling programme) instead of being outcomes-focused (for example, ensuring that trainees join jobs and stay in jobs after skilling). Furthermore, calculations show that of every 100 women enrolled in skilling programmes in India, only ~10 stay in post-skilling jobs for three months or more (Business Standard, 2021). Similarly, under CSR programmes, a study found that of the top 100 companies in 2017, only seven companies disclosed that trainees were tracked after their programmes and six reported supporting post-placement linkages (Parekh et al., 2020). The challenges faced by governments and the private sector to comprehensively address Female Labour Force Participation Rate (FLFPR) are not simply a function of lack of resources, these are often related to how these resources are deployed as well. Rethinking current approaches to moving towards outcomes can enable women to not only enter the workforce, but also stay and grow within it.

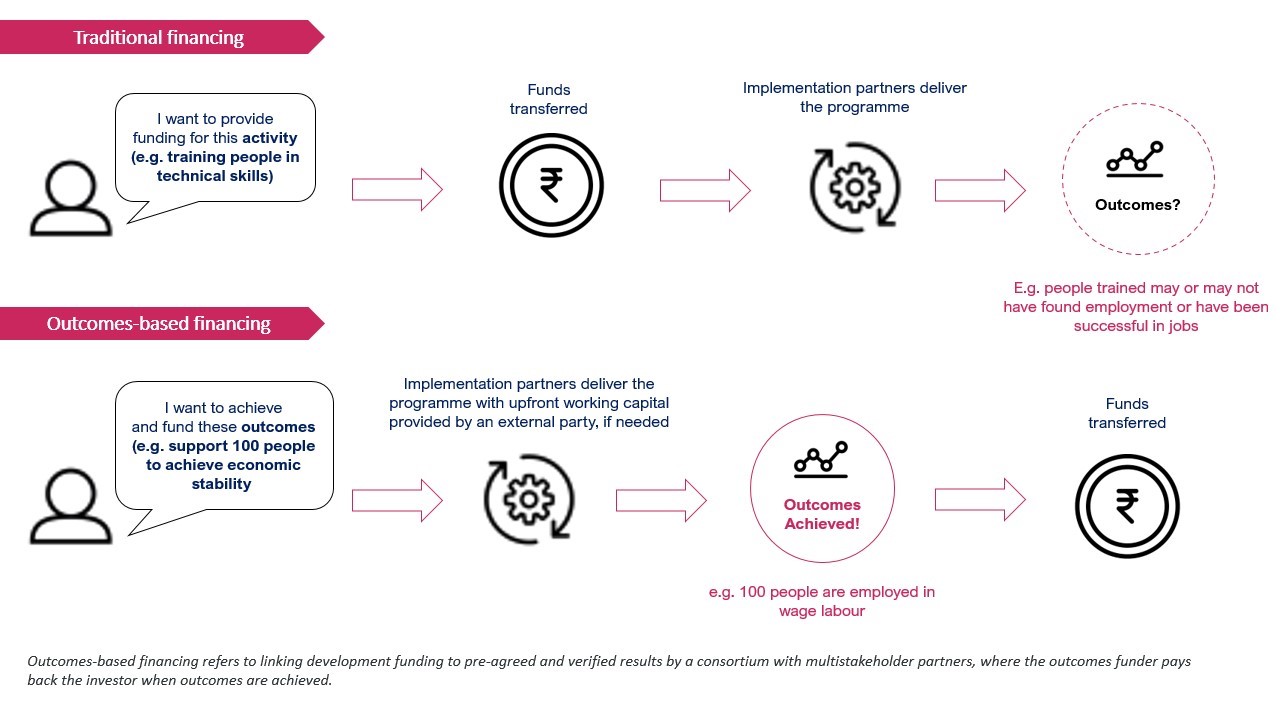

Over the past few years, outcomes-based financing (OBF) has emerged as a promising way to address the intractable challenges, such as declining Female LFPR. OBF instruments tie the disbursement of funding for development projects to the achievement of independently verified results that are closely related to the ultimate development objective—i.e., outcomes—as opposed to actions, inputs, and activities.

OBF presents an innovative approach to funding, designing, and implementing social development policies and programmes, wherein payments are linked to results; the government/private outcome funder pays only for the outcomes achieved, thereby receiving a higher value for money and ensuring that there is an alignment of a diverse range of stakeholders and their incentives for working towards a common goal. Some types of OBF instruments include impact bonds (IB), impact guarantees, result-based financing contract, and social success note (SSN). This Policy Brief focuses on impact bonds.

Figure 2: Outcomes-Based Financing Explained

Source: British Asian Trust

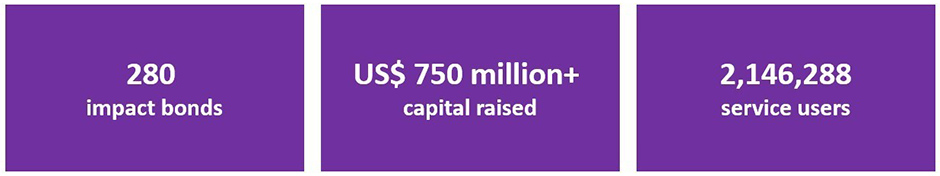

There are 280 impact bonds across the world, as shown below.

Figure 3.1: Impact Bonds Around the World

Source: Government Outcomes Lab Impact Bonds Dataset

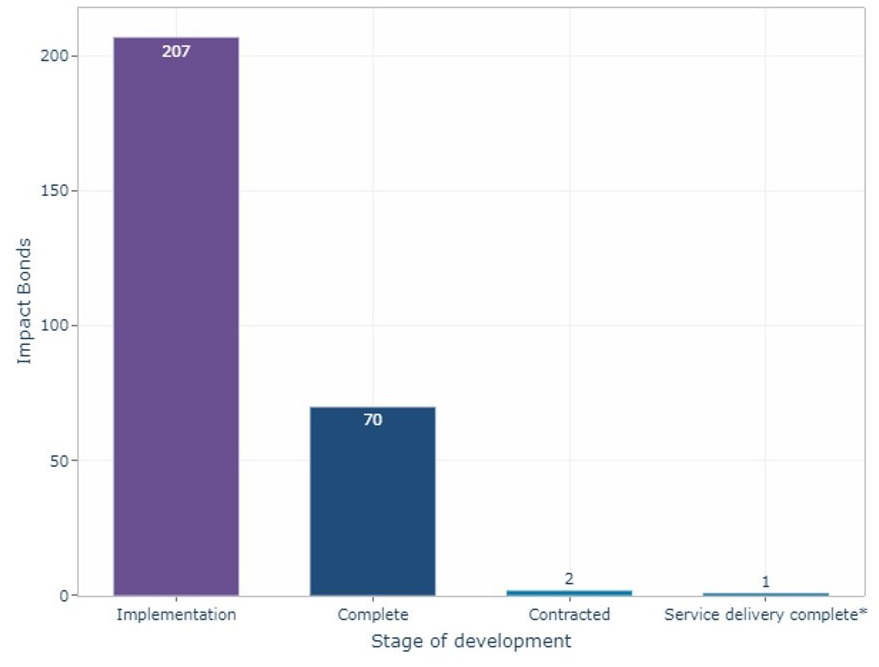

Figure 3.2: Stages of Development of Impact Bonds

Source: Government Outcomes Lab Impact Bonds Dataset

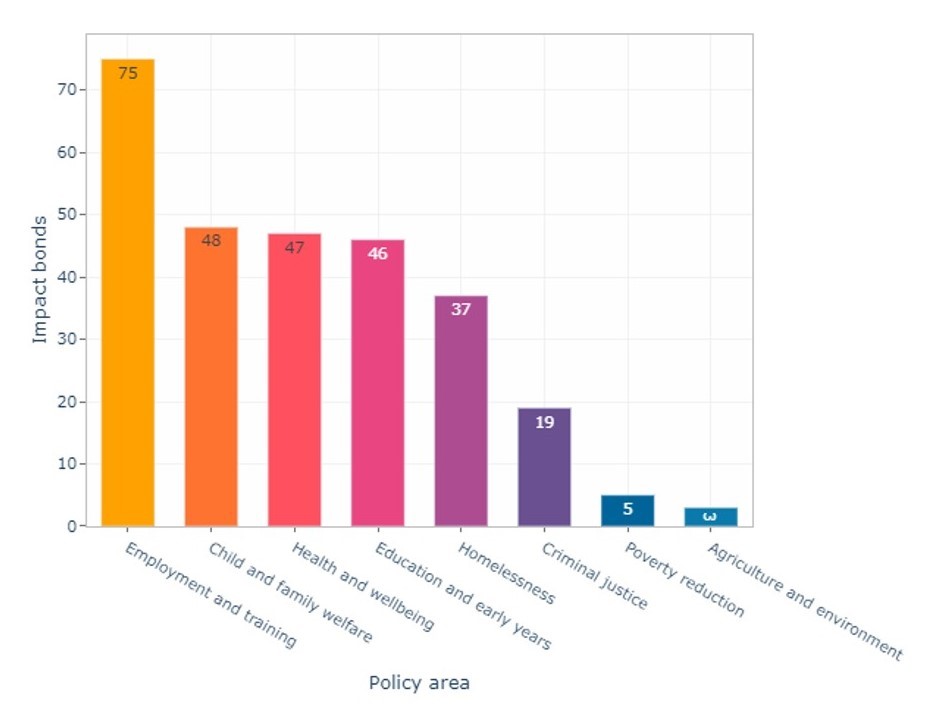

Figure 3.3: Policy Sectors of Impact Bonds

Source: Government Outcomes Lab Impact Bonds Dataset

A growing body of evidence (Carter et al., 2018) around these impact bonds across the world shows early and promising results (Gustafsson-Wright et al., 2020) regarding how well-designed OBF can contribute to:

- clearly defined outcomes and rigorous and independent verification of these outcomes;

- payments linked to achievement of outcomes;

- appropriate transfer of risk, when needed, to provide flexibility to innovate on delivery processes;

- robust performance management and data-driven decision-making; and

- strong governance, transparency, and accountability.

However, barriers remain with regard to the adoption of OBF. A lack of awareness and education around the evidence emerging from this space significantly affects buy-in, particularly within governments in countries that may benefit the most by employing OBF. Even when the initial buy-in is secured, barriers, such as complications with design, contracting, regulations, and capacity of stakeholders, often impede adoption or result in protracted timelines. Ultimately, the application of these innovative partnerships and financing frameworks is still at a nascent stage. Only with improved visibility and awareness of data and evidence, emerging from these applications, can governments and private capital from around the world begin to engage effectively, and accelerate the impact and scale of these partnerships.

2. The G20’s Role

As the premier forum for international economic cooperation, the G20 is uniquely placed to create an enabling environment needed to promote OBF as an innovative approach to fostering collaboration and financing for addressing low Female LFPR.

Together, the members of the G20 represent 85 percent of global GDP, 75 percent of international trade, and two-thirds of the world’s population (G20, 2023). Economic reforms that enable women’s empowerment for socioeconomic progress are a key priority area for the G20, given the commitment made by its leaders at the 2014 summit in Brisbane (ILO, 2017). Progress amongst member countries on reaching this goal will go a long way in achieving the 2030 targets for sustainable development, especially as it relates to Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 8, seeking inclusive and sustainable economic growth, and decent work for all.

The role the G20 plays allows member countries to engage in dialogues, discussions, and nuanced analysis of the use of OBF for boosting women’s workforce participation. The G20 also allows countries to share what they have learnt internally as well as from other countries. In supporting OBF, the G20 can further build on the wide evidence base to establish that these models work across varied contexts, geographies, and policy areas. The diversity and comprehensiveness of the G20 Engagement Groups ensure that almost every stakeholder, required to take an idea to action, is covered under their ambit—from industry and civil society, to think tanks, bureaucrats, and policymakers. Additionally, the T20, in its role as the idea bank for the G20, can cross-fertilise ideas and foster future-facing innovation with regard to how challenges are addressed. The G20 can thus create a catalytic platform to unlock the potential of OBF on a scale and in a manner that is critical to filling the SDG financing gap in the 2030 Agenda (UN Sustainable Development Group, 2023).

3. Recommendations to the G20

a. Given the growing evidence base, encourage adoption of OBF principles in design and implementation of schemes and programmes, aimed at improving Female LFPR.

With the increased uptake of OBF models worldwide, policymakers are being afforded an evidence base for what constitute a well-designed OBF. These include achieving livelihood outcomes, shifting focus from inputs to outcomes, delivering under pressure and external shocks, and catering better to last-mile populations.

i. OBF can deliver on employment/livelihood outcomes.

Overall, a review of 194 impact bonds (Gustafsson-Wright et al., 2020) shows that they deliver outcomes: out of the nearly 50 completed impact bonds, outcomes have been achieved and investors have been repaid in all but two cases. Most impact bonds that have come to a close are in the social welfare and employment categories (Gustafsson-Wright et al., 2020).

The results for a subset of these, where more details are available, are outlined below. –

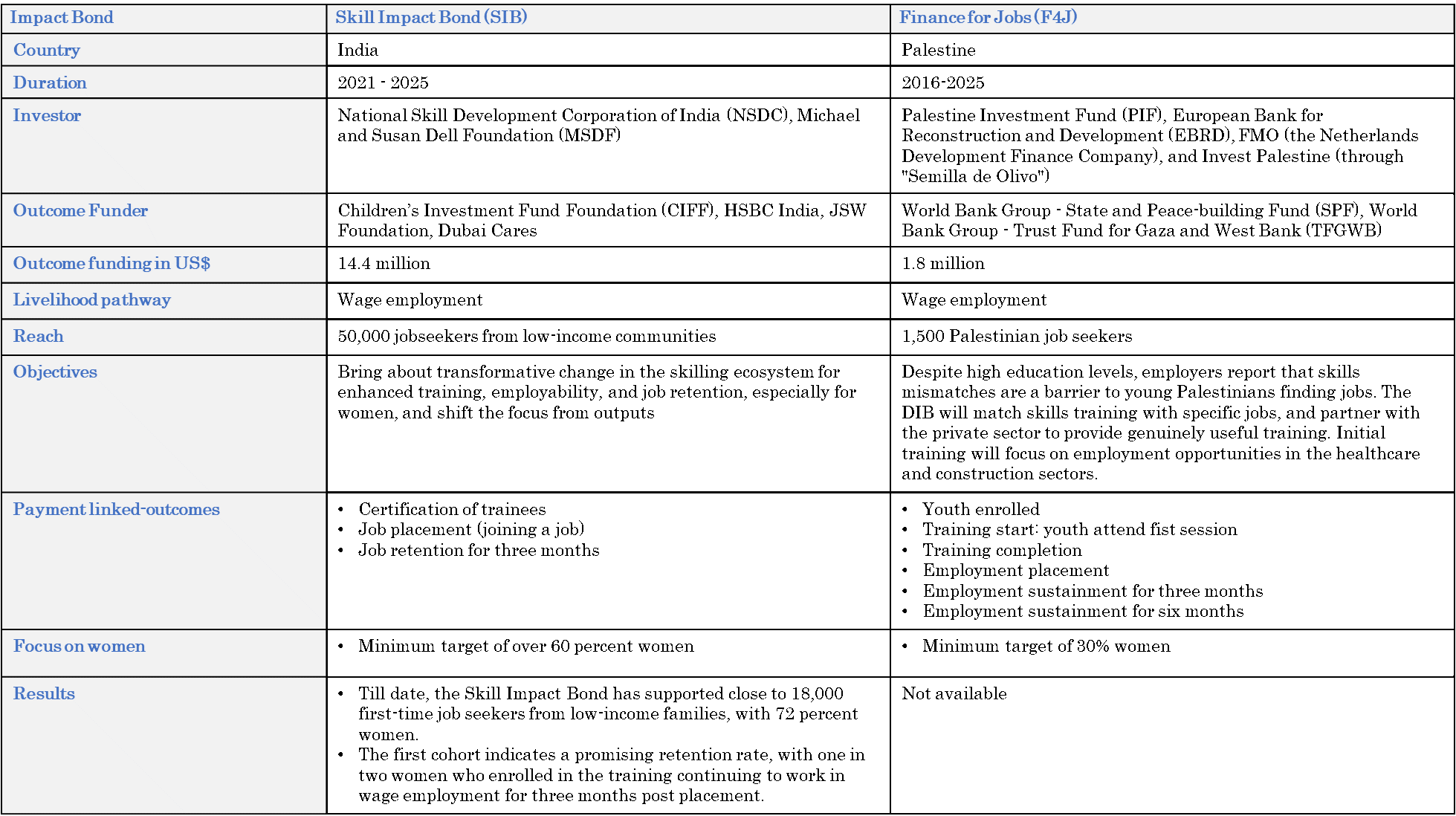

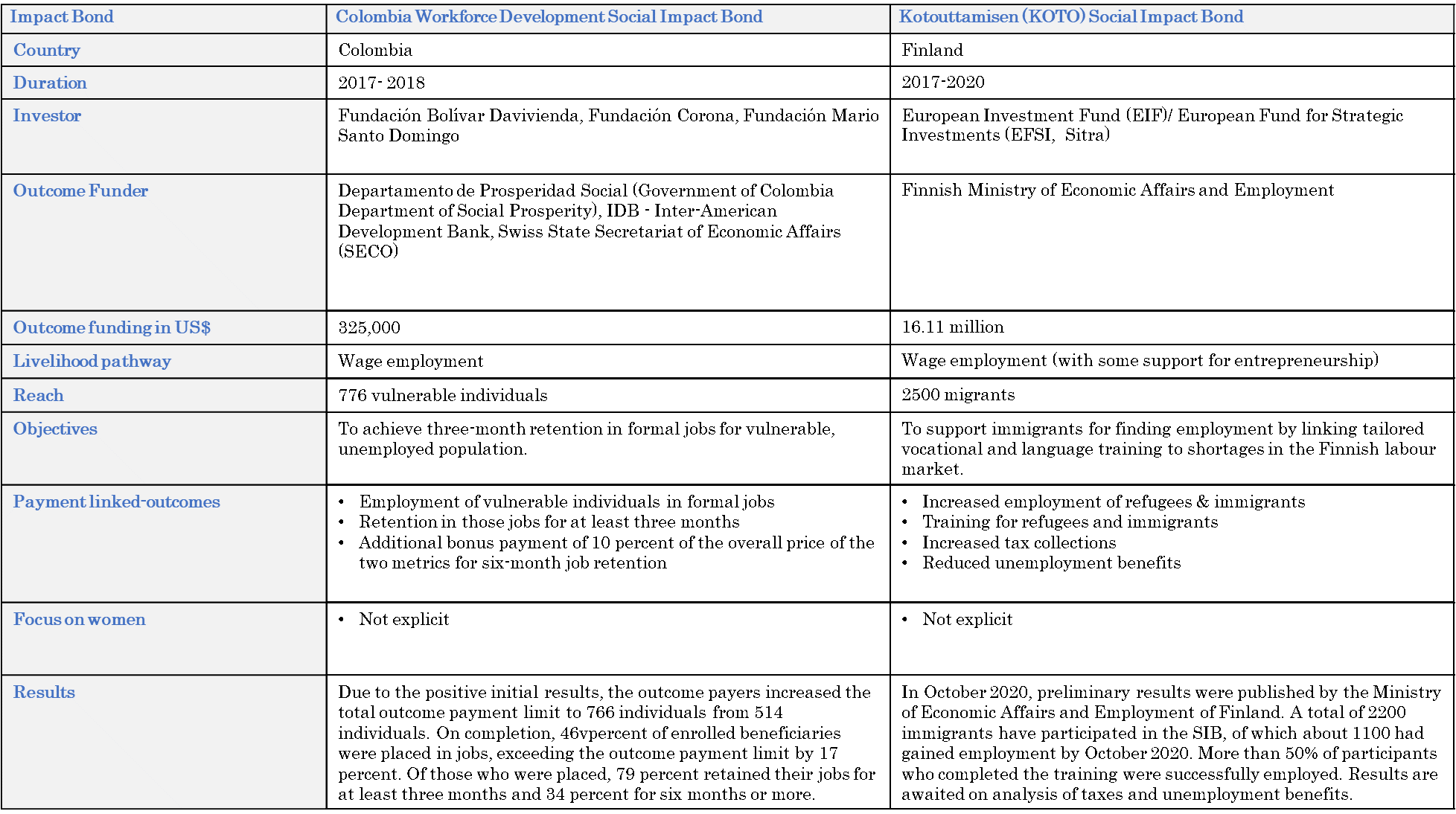

Table 1: Selection of OBF projects focused on improving Female LFPR

ii. Well-designed OBF structures have the potential to shift focus from inputs to employment/livelihood outcomes.

Out of the 194 projects in the Brookings Global Impact Bonds Database in 2020, 109 tied investor repayments to outcomes while 49 tied investor repayment to a mix of outcomes and outputs. Often, the mix represents projects wherein outcomes may emerge over the life of the projects, with outputs representing interim indicators of success or failure. In cases where outcomes may be difficult to measure and attribute, the inclusion of outputs serves to temper the risk for investors while the linkage to outcomes can serve to create an evidence base and shift the focus to outcomes over time.

An example of this is the Skill Impact Bond, which uses a sliding scale to repay investors, starting closer to outputs and the current status quo, and progressively pushing the proportion linked to final outcomes to an aspirational stage, with ambitious gender targets in place. This innovative element allows for a period of acclimatisation and capacity augmentation for all stakeholders. Similarly, Finance for Jobs (F4J) tracks a clear trajectory for each trainee (Khatib et al., 2021), using a mix of outputs and outcomes. This initially focuses on programme milestones (participant intake, start of training, training completion, employment placement), and also links payment to longer-term outcomes (employment sustainment for three months, employment sustainment for six months).

iii. OBF can encourage process innovation, flexibility, and customisation needed to build a strong and nuanced gender lens in policies and programmes for improving Female LFPR.

An external review (Menon et al., 2019) of around 50 public policies/schemes for improving the Female LFPR in India showed that most schemes and interventions focused on inputs, such as financial assistance, scholarships, vocational training, material, infrastructure, and placements for women. Few offered support services, such as lodging, safe travel, migration support, and post-placement counselling, which enable women to stay in their jobs. Even fewer addressed sociocultural and familial barriers preventing women from joining or staying in the labour force. An outcomes-based approach to Female LFPR interventions ensures that the design and implementation consider how these inputs translate to desired outcomes, and therefore, incorporate all essential components required for the outcomes to materialise. By providing upfront working capital and transferring the risk of failure to an investor, OBF tools, such as impact bonds, can afford the flexibility required to innovate, experiment, and pivot to an implementing partner, without getting prescriptive about inputs.

For example, Skill Impact Bonds in India incentivises implementers to adopt a gender lens. This would allow them to hypothesise that women require additional support to stay in work by countering systemic barriers, introducing enabling elements such as counselling and handholding within the training lifecycle, and tackling gender biases. It costs more to support women and therefore, the development impact bond provides differential outcome payments for men and women. The policy implications of this for gender budgeting are significant as shifting the focus on outcomes can help discover true costs and budget accordingly.

iv. OBF tools have been pressure-tested for external shocks and can provide flexibility and adaptability that allow the instruments to address service delivery failure for specific demographics and contexts.

OBF instruments have been deployed in many different contexts—in ‘business as usual’ circumstances as well as in more volatile contexts or for more vulnerable/marginalised populations, as seen in the case of the Jordanian Refugee Impact Bond, the Norwegian KOTO SIB or the Finance for Jobs impact bond in Palestine. These contexts are marked by relatively higher political, economic, and social risks, together with weak institutional capacity and limited financial resources.

Additionally, the ability of OBF instruments to withstand external crises and adapt to delivery models has also been tested by the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. The Village Enterprise DIB, for example, was able to sustain itself through the pandemic. The final evaluation report, released in 2022, showed that even with 87 percent of respondents indicating that they were negatively impacted by COVID-19, the programme shielded participants from the worst of the pandemic’s economic impact by sustainably improving their livelihoods through intensive poverty alleviation efforts (Gallardo et al., 2021). OBF can be used as a tool to incentivise service providers to work with last-mile, vulnerable populations, such as those with mental or physical disabilities, or those who have dropped out of school, who may otherwise fall through the cracks and who require more specialised delivery and different price structures.

The ability of these tools to address different levels of vulnerability and uncertainty is a promising sign. They can assist women in crisis situations who face increased vulnerabilities, providing them opportunities for economic empowerment.

b. Create a cross-sector task force on OBF as a facilitating platform for member countries to engage with evidence on how OBF can improve female labour force participation.

Increasing female labour force participation is an essential step towards achieving goals, such as gender equality (SDG 5), decent work and economic growth (SDG 8), and reduced inequality (SDG 10). A cross-sector task force to apply OBF to solving low Female LFPR issues can be created through the G20’s various Engagement Groups, such as Women20, Business20, G20 Empower, Think20, Civil20, and Startup20, which not only have a vested interest in improving Female LFPR, but can also bring unique strengths and possible solutions to the challenges at hand.

For example, two of the five priority areas of W20 under India’s presidency—i.e., women in entrepreneurship, and education and skill development—can immediately benefit from an OBF lens, as explained in examples used in Section 3.1. Similarly, within the Buisness20, OBF lens can be applied to improving recruitment, retention, and career growth practices for women under corporate priorities of gender diversity and inclusion, and environmental, social, and corporate governance (ESG) commitments. OBF can also help achieve the objectives under the future of work and digital skilling agenda, with efforts focused on skilling/upskilling/re-skilling women for future-ready and aspirational jobs, which is a recurring priority across B20, W20, and G20 Empower. Similarly, beyond the financing role, OBF can also lead to effective multistakeholder partnerships, which can be harnessed to enable synergies among startups, corporates, investors, innovation agencies, and other key ecosystem stakeholders to promote women-owned enterprises under Startup20.

The task force’s mandate can include exploring how OBF frameworks can be applied to addressing various SDGs, with a priority of improving Female LFPR. Evidence generated by OBF can be cross-fertilised between Engagement Groups through the task force, which can function as a centre of excellence that guides the G20’s action for OBF. This can be carried out in a way similar to how the G20’s Sustainable Finance Working Group is tasked with the dual objectives of identifying institutional and market barriers to sustainable finance (G20 Sustainable Finance Working Group, 2023), and consequently, developing methodologies to overcome these barriers or how the G20’s Global Blended Finance Alliance (Tri Hita Karana Forum, 2022) is working towards unlocking new forms of capital to support the SDG funding gap.

The task force can also be entrusted with the responsibility of creating facilitating platforms, hosting convenings, and building partnerships with practitioners, academia or think tanks to enable G20 member countries to improve awareness of and learnings from OBF for women’s economic empowerment and help adoption. Carefully curated forums can also help break siloes and facilitate dialogue among policymakers, academia, practitioners, and think tanks to openly discuss both challenges and learnings from case studies, currently being conducted in member countries.

c. Encourage member states to create a conducive ecosystem for nuanced understanding and use of OBF.

OBF instruments are different from traditional, input-based funding mechanisms, and therefore, require a set of enabling conditions to take root. The ecosystem readiness framework (Savelle et al., 2022), created by Social Finance, the UK, after synthesising insights from high-, middle-, and low-income countries that have used OBF, highlights five competencies required for OBF:

- demand from outcome funders, their willingness, awareness, financial capacity, and ability to support other ecosystem stakeholders to engage in OBF;

- regulatory framework, rules, and procedures that enable outcome funders, including governments, to procure and contract services, using OBF, and permit easy blending of public and private capital;

- economic and political context that can influence the degree of confidence non-state actors have in OBF;

- availability of data, evidence, and benchmarks around population needs, existing interventions, outcomes, and costs; and

- market capacity and competencies of service providers, intermediaries, and evaluators

Several member countries within the G20, such as the UK, have made significant progress on easing the way for OBF with regard to the five dimensions mentioned above. It is recommended that the G20 encourage member states, which have successfully adopted and rolled out programmes to address Female LFPR via OBF models, to share their learnings and experiences to demystify the model’s design, purpose, and impact for other member states, willing to trial such instrument, and support a nuanced understanding of when and how OBF can be a powerful tool, and how to employ it successfully through rigorous design, implementation, and evaluation. Cross-sharing can also help create a more enabling environment for OBF to thrive.

Attribution: Abha Thorat-Shah, Anushree Parekh and Smita Jacob, “Improving Female Labour Force Participation through Outcomes-Based Financing,” T20 Policy Brief, July 2023.

The authors gratefully acknowledge the evidence and research support provided by the Government Outcomes Lab, Blavatnik School of Government, University of Oxford.

Bibliography:

Carter, Eleanor, Clare Fitzgerald, Ruth Dixon, Christina Economy, Tanyah Hameed, and Mara Airoldi. Building the Tools for Public Services to Secure Better Outcomes: Collaboration, Prevention, Innovation. Oxford: Government Outcomes Lab, University of Oxford, 2018.

G20. “G20 – Background Brief.” Accessed March 24, 2023.

G20 Sustainable Finance Working Group. “Progress Tracking.” Accessed March 24, 2023.

Gallardo, Miguel Angel Jimenez, Winfred Kananu, Christy Lazicky, Jeffery McManus, and Frida Njogu-Ndongwe. Village Enterprise Development Impact Bond Evaluation Findings. San Francisco: IDinsight, 2021.

Gustafsson-Wright, Emily. “What is the size and scope of the impact bonds market?” Brookings, September 2, 2020.

Gustafsson-Wright, Emily, Meg Massey, and Sarah Osborne. “Are impact bonds delivering outcomes and paying out returns?” Brookings, September 16, 2020.

Gustafsson-Wright, Emily and Sarah Osborne. “Are impact bonds reaching the intended populations?” Brookings, September 9, 2020.

Gustafsson-Wright, Emily and Sarah Osborne. “Do the benefits outweigh the costs of impact bonds?” Brookings, September 30, 2020.

Gustafsson-Wright, Emily, Sarah Osborne, and Meg Massey. “Do impact bonds affect the ecosystem of social service delivery and financing?” Brookings, September 23, 2020.

International Labour Organization (ILO). “Women at Work in G20 Countries: Paper Prepared for the Labour and Employment Ministers Meeting 2017.” Accessed March 24, 2023.

International Labour Organization (ILO). “Women at Work in G20 Countries: Progress and policy action in 2020.” Accessed March 24, 2023.

International Labour Organization (ILO). “Women’s Labour Force Participation in India: Why Is It so Low?” Accessed March 24, 2023.

Khatib, Abed, Jade Ndiaye and Stefanie Ridenour. “Palestinians Benefitting from Jobs and Training despite COVID-19 Thanks to Innovative Development Impact Bond.” World Bank, September 8, 2021.

Menon, Sneha, Dona Tomy, and Anita Kumar. Female Work and Labour Force Participation in India – a Meta Study. Bangalore: Sattva, 2019.

Ministry of Skill Development and Entrepreneurship. “Notes on Demands for Grants, 2023-2024.” Accessed April 6, 2023.

National CSR portal, Ministry of Corporate Affairs. “Explore CSR data”. Accessed March 24, 2023.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). “Monitoring Progress in Reducing the Gender Gap in Labour Force Participation.” Accessed March 24, 2023.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). “Women at Work in G20 Countries: Policy Action since 2020 Paper Prepared for the 2nd Meeting of the G20 Employment Working Group under Italy’s Presidency 2021.” Accessed March 24, 2023.

Parekh, Anushree, Ragini Menon, Sandhya Tenneti, and Aayushi Khare. Corporate Engagement in Women’s Economic Empowerment: What Are India’s Top 100 Companies up To? Mumbai: Samhita, 2020.

Pradhan Mantri Kaushal Vikas Yojana. “Dashboard”. Accessed March 24, 2023.

Press Trust of India, “India’s first ‘Skill Impact Bond’ launched, fund to benefit 50,000 youth.” Business Standard, October 26, 2021.

Savelle, Louise, Saskia Thomas, and Maria Alejandra Urrea. Engaging in outcomes-based partnerships: A framework to support government and ecosystem readiness. London: Social Finance, 2022.

Tri Hita Karana Forum. “Global Blended Finance Alliance”. Accessed March 24, 2023.

UN Sustainable Development Group. “2030 Agenda – Financing and Funding.” Accessed March 20, 2023.

United Nations. “World Population Prospects Data Booklet.” Accessed March 24, 2023.