Task Force 1: Macroeconomics, Trade, and Livelihoods: Policy Coherence and International Coordination

Abstract

The premise that countries that trade are less likely to go to war is in urgent need of revisiting and refreshing. With respect to strategy, policy, and targeted measures, this policy brief distinguishes between conceptually quite distinct, even if mutually supportive, trade- and investment-related interventions. Specifically, this brief provides G20 policymakers with a framework to better understand and use trade and investment for peace and stability (TIPS), known as the TIPS Framework. This is critical to the G20’s role in global security and cooperation. The TIPS Framework is grounded in empirical evidence and composed of 12 guiding principles that can help orient and inform TIPS strategy and policy, coupled with 12 targeted measures to operationally leverage trade and investment for peace and stability.

1. The Challenge

• Trade and Peace

The premise that nations that trade are less likely to go to war is known as the ‘liberal peace’ theory. It traces its origins to Montesquieu (1758) and Immanuel Kant (1795) and was further advanced by John Stuart Mill (1909) and Joseph Schumpeter (1919). . It is grounded in the insight that countries that trade with each other are less likely to go to war as they would lose the mutually beneficial gains from trade.

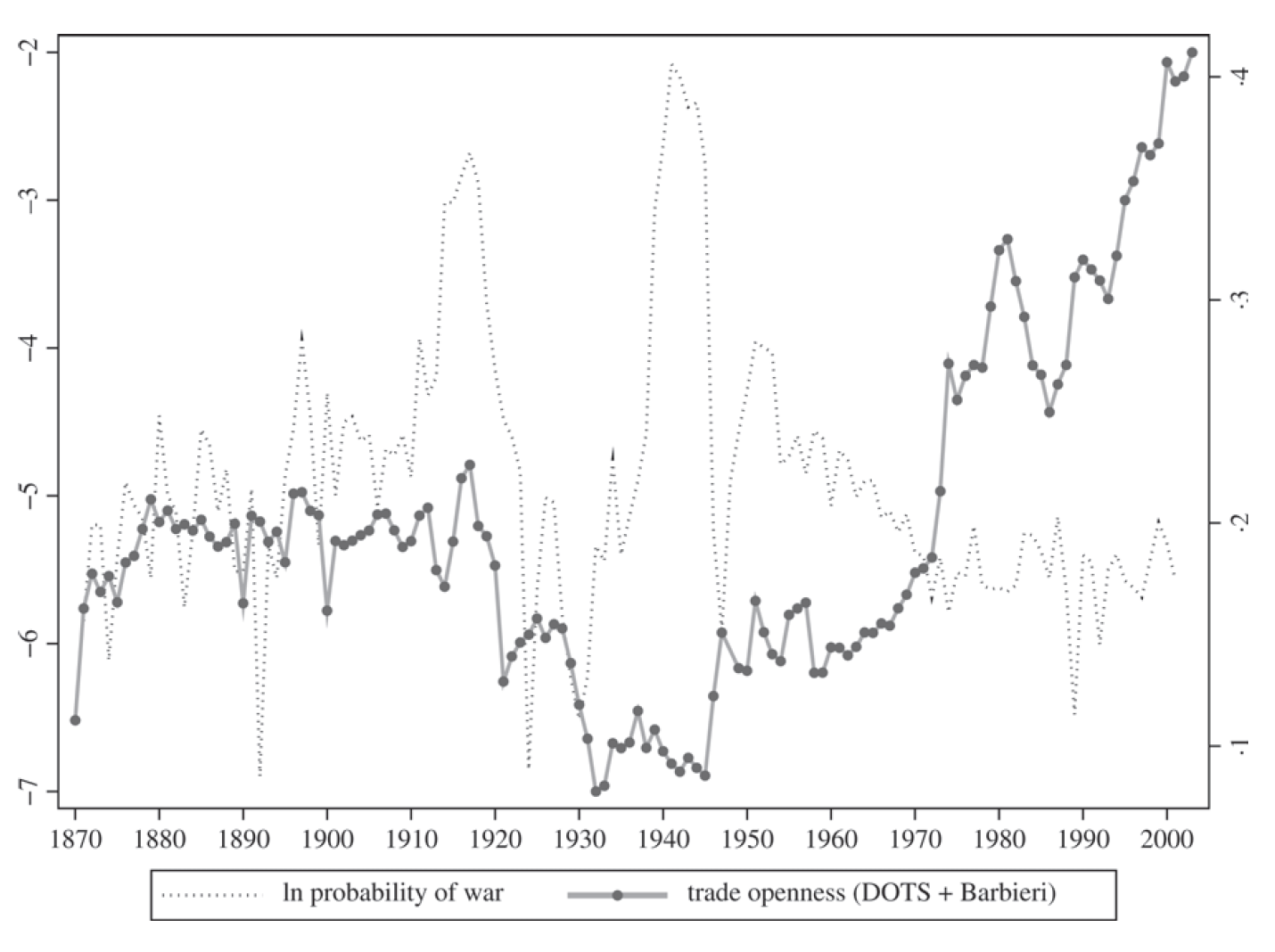

However, the evidence is not so clear cut. There are many examples of nations that had very deep trade relations, and yet still went to war, such as Germany, the UK, and France in the First World War. Figure 1 charts trade openness versus the probability of military conflict, and shows that the two do not always move together. For instance, from 1880 to the First World War, trade openness remained steady, or even increased slightly, while the probability of military conflict escalated rapidly, and eventually occurred.

Figure 1: Military conflict probability and trade openness over time (1870-2000)

Source: Martin et al. (2008), p. 866

Data shows that the liberal peace theory holds more in the Second World War: trade openness fell significantly in the run up to the war, and the probability of conflict increased sharply. Following the Second World War, the theory seems to hold at a macro level; from 1950 onwards, trade openness grew while the probability of war declined.

However, there are several more recent cases that call for a better understanding of these dynamics. The ongoing war in Ukraine and border clashes between India and China, along with many other hotspots around the world, creates an urgency to understand how trade and investment can impact peace and stability between countries.

Consider recent data. In 2021, the year immediately prior to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, trade between the two countries represented just 1.8 percent of Ukraine’s GDP, and 0.5 percent of Russia’s GDP. These low numbers bolster the theory that deep trade relations contribute to peace—in this case, the trade relations were shallow, and had been falling over time.

In contrast, there are two striking examples where significant conflict has not taken place even though tensions have flared.

China and India experienced border clashes in 2020 and early 2021, yet this did not erupt into a larger conflict, as happened in 1962. In 2021, trade between the two countries reached record levels, surpassing US$100 billion for the first time. India’s imports from China increased by 46 percent to reach US$98 billion, while Indian exports to China increased by 34 percent to reach US$28 billion (The Wire, 2023).

Regarding the Taiwan Strait, trade between China and Chinese Taipei has grown while tensions have also increased, though they have not escalated to conflict. In 2021, about 22 percent of Chinese Taipei’s imports came from mainland China and Hong Kong, while 42 percent of its exports went to mainland China and Hong Kong (Cheng, 2022). Cross-Strait trade has grown significantly over the past 20 years (see Figure 2), with China becoming Chinese Taipei’s leading trade partner in 2005.

Figure 2: Trade between China and Chinese Taipei (2001-2021)

Source: Chinese Taipei government.

While tensions have risen in both cases (India-China, and China-Chinese Taipei), conflict has not taken place. Is this due to the incredibly deep trade ties between the two economies, or are there other factors at play?

The academic literature that examines the interaction of trade and investment with peace and stability—and especially seeks to identify causal determinants—is inconclusive although helpful. It can help orient G20 consideration of actions to grow trade and investment for peace and stability. G20 action can be informed by a series of 12 principles and 12 measures by using trade and investment for peace and stability (TIPS; presented in the recommendations section of this brief), but foreshadowed in parentheses (for example, ‘cf. TIPS Principle 2’) to link the evidence with the recommendations.

Keshk et al. (2004) and Kim and Rousseau (2005) examine the relationship between trade and conflict econometrically and conclude that trade does not deter conflict.

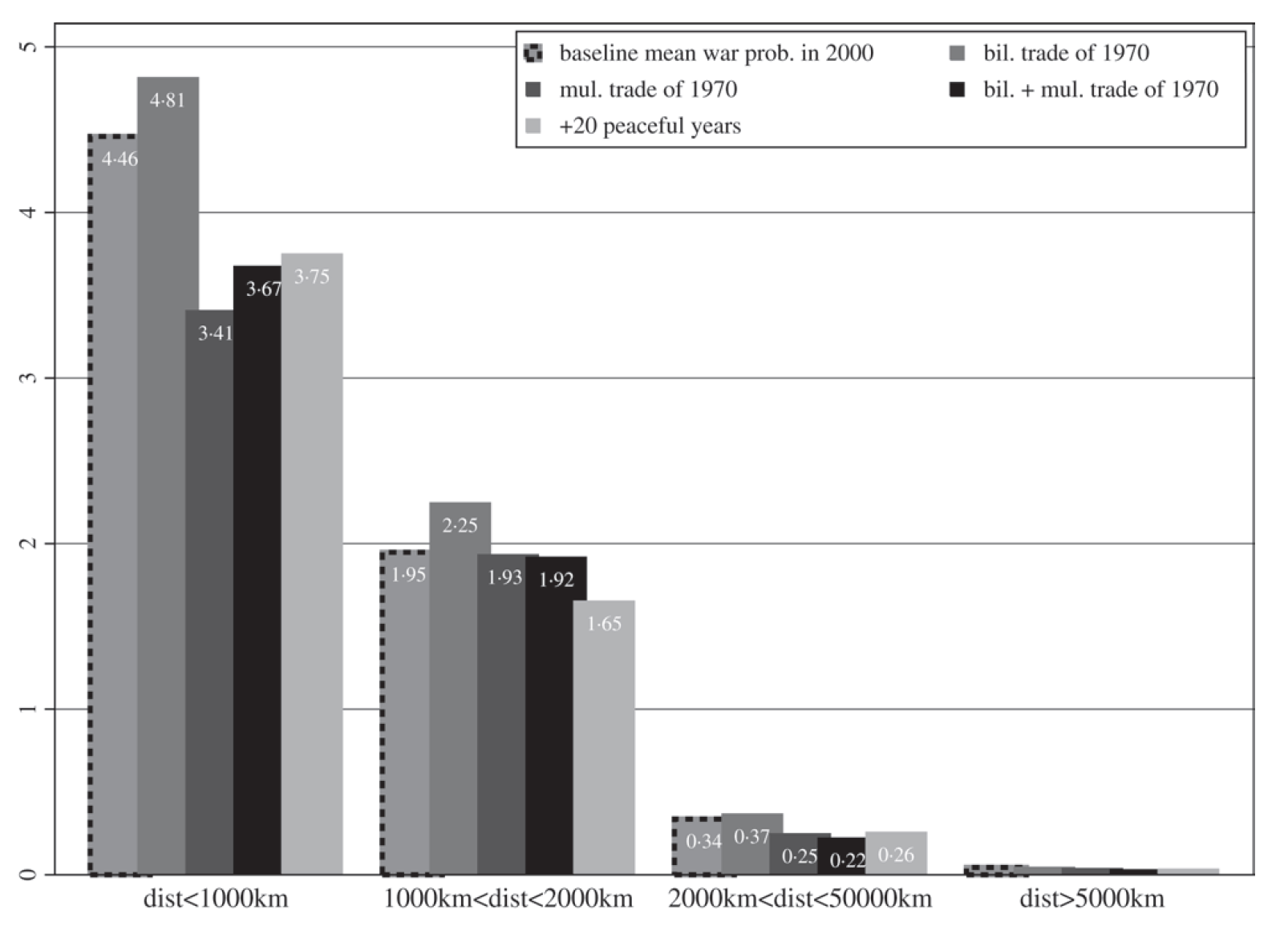

Yet, later studies reach different conclusions. Martin et al. (2008), examining a large dataset of over 200,000 dyadic relationships from 1950 to 2000, finds a two-sided relationship between trade and conflict: positive for bilateral trade and negative for multilateral trade. In other words, bilateral trade decreases bilateral conflict, but multilateral trade openness increases the probability of bilateral conflict because the cost of bilateral conflict is lower between any pair of countries, whereas multilateral openness provides alternative trading partners. Because of the alternatives, the incentives to make concessions to avert escalation are weakened. There is a related trade-off between deepening bilateral trade relations (increasing efficiency) and diversifying multilateral trade relations (increasing resilience to shocks) (Gölgeci et al., 2020; Reeves et al., 2020; Reinsch, 2021; and Tagliapietra, 2023). The right balance needs to be struck between these competing goals (cf. TIPS principle 1).

Geographic distance between economies also emerges as a key determinant in the interaction between trade and conflict. In other words, contiguous countries are much more likely to go war, and the probability diminishes as distance grows. Figure 3 shows Martin et.al’s (2008: 889) estimates of the impact of bilateral and multilateral trade when considering distance (km) (cf. TIPS principle 2).

Figure 3: Military conflict probability, trade, and geographic distance

Source: Martin et al. ( 2008), p. 889

The issue is far from settled. Lee and Pyun (2009) and Hegre et al. (2010) find that trade categorically diminishes the probability of conflict, when not only properly accounting for distance between the countries but especially the size of the countries, which they use as a proxy for power. In other words, two very close, very powerful countries may still go to war even if they have very significant bilateral trade: “Large, proximate states fight more and trade more.” (Hegre et al., 2010: 771) (cf. TIPS principle 3).

McDonald (2004) offers an explanation: it is not trade per se that affects the probability of conflict, but free trade. Free trade reduces the domestic political power of interests that are protected by barriers to trade. Sectors relying on trade protection may even actively support aggressive foreign policies that reduce imports and foreign competition, expanding their share of the domestic markets. Applying this lens to France-Germany and China-India, the explanation then becomes that France and Germany, while they traded a lot, had very protective trade policies at the time, while India and China had relatively less protective bilateral trade policy, brought about by their membership of the World Trade Organization, especially the concessions that China had to provide to join in 2001 given that it was not a founding member. (cf. TIPS principle 4).

This finding is bolstered by considering a third region, South America, where Argentina and Brazil (two large, proximate states) created the Southern Common Market (Mercosur) in 1991 to help avoid military conflict through growing trade relations, and have since not had military conflict, which they did prior to the agreement.

A promising new line of thinking is whether the relationship between trade and peace depends on what is being traded. Some trade may be of imperfect substitutes (for instance, bananas and apples, both fruit), and some of complements, especially intermediate inputs into production processes constituted by global value chains. Trade in complements will diminish the probability of bilateral conflict more than trade in imperfect substitutes as the former creates an alignment of interests in continuing trade relations that are mutually beneficial, while the latter does not (cf. TIPS principle 5).

This line of thinking is bolstered when looking at the composition of trade between India and China. In 2021, the main products that China exported to India were computers (US$6.34 billion), telephones (US$4.42 billion), and semiconductor devices (US$4.25 billion), while the main products that India exported to China were iron ore (US$3.51 billion), refined petroleum (US$1.61 billion), and raw aluminium (US$1.26 billion) (OEC, 2023). One can clearly see that India’s exports are of primary products while China’s are of finished products, demonstrating trade in complements rather than trade in substitutes.

Trade in complements will create mutual dependency, which can lead to two very different outcomes: (1) stability, with both parties having an interest in maintaining the status quo, versus (2) tension, with one party feeling more dependent on or vulnerable to the other. This vulnerability can then be mobilised to exert power over the other party, creating resentments but also a desire to break the dependency (Hirschmann, 1945). If two states are more or less equally powerful, this could lead to conflict. This brings the argument back to TIPS principles 1 and 3—finding the right balance between deepening the mutual dependence through trade and building resilience through diversification, and paying special attention to relations between large trading partners as these can have conflict even with significant trade relations.

• Investment and Peace

Regarding the relationship between foreign direct investment (FDI) and peace and stability, the arguments and evidence do not go back as far, but the importance of leveraging FDI to contribute positively to peace and stability in the aftermath of conflict has been examined in detail more recently.

Foreign private-sector players have historically been wary of investments in peacebuilding situations due to the prevailing risk–reward estimates (Berdal and Mousavizadeh, 2010). However, large investments are needed to help catalyse and keep the peace, by restarting the economy and providing employment. At the same time, there is the risk that FDI could contribute to conflict and instability. Conflict-insensitive FDI could, for instance, destabilise domestic political processes if it favours one group of power brokers over another or provides resources to acquiring further weapons.

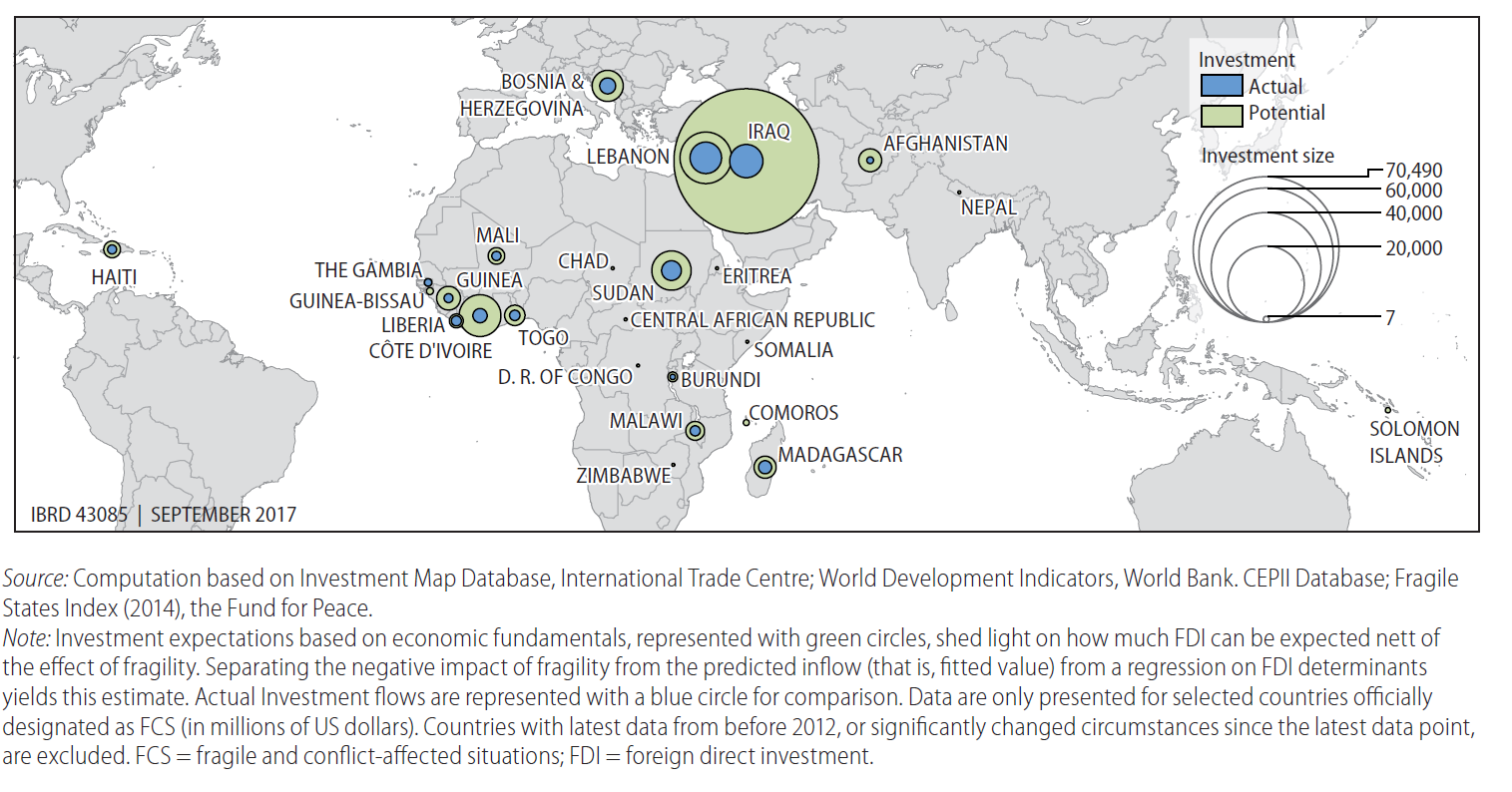

The real challenge is to grow FDI that contributes to peace and stability under difficult investment climate conditions. Figure 4 shows how much FDI fragile and conflict-affected states have received compared to their estimated potential, considering FDI determinants such as market size and domestic resources.

Figure 4: FDI Flows to fragile and conflict-affected states are below their estimated potential (2008–14)

Source: Ragoussis and Shams (2018) p. 138.

Yet even under difficult investment climate conditions, there are opportunities. Many fragile and conflict-affected states have natural resources, including minerals, metals, and oil. If structured appropriately, investment in these resources can anchor stability and growth. Figure 5 shows that natural resource sectors receive a much greater share of FDI in FCS countries compared to low-income non-FCS countries.

Figure 5: Distribution of FDI across sectors (FCS vs non-FCS)

Source: Ragoussis and Shams 2018: 143

Therefore, and as Berdal and Mousavizadeh (2010) argue, “an important starting point in re-examining the role of natural resources in peacebuilding is to recognise that, for a number of developing countries, minerals and petroleum offer the biggest and most accessible source of income.” Rather than shy away from such investments, it may be preferable to structure them in a way that contributes to peace and stability, for instance through ensuring transparent and equitable revenue management, which may only be effective through the application of home-country due diligence requirements (Draper et al., 2023). This will determine whether FDI in these resources deepens fissures within a society or creates a common basis for economic progress (Draper et al., 2023). The natural resource curse for the bottom billion can be reversed with the right guardrails (Collier, 2007) (cf. TIPS principle 6)

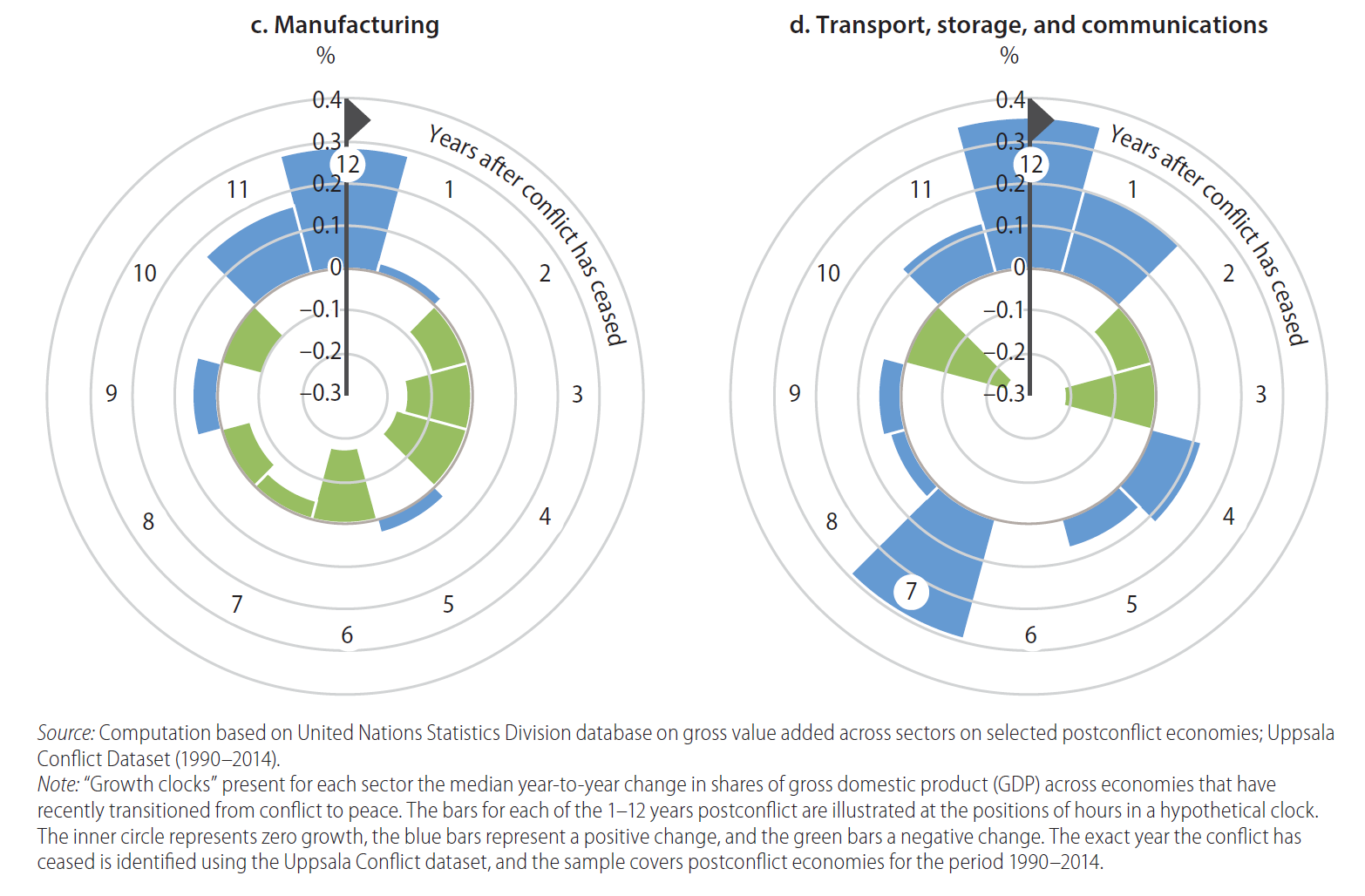

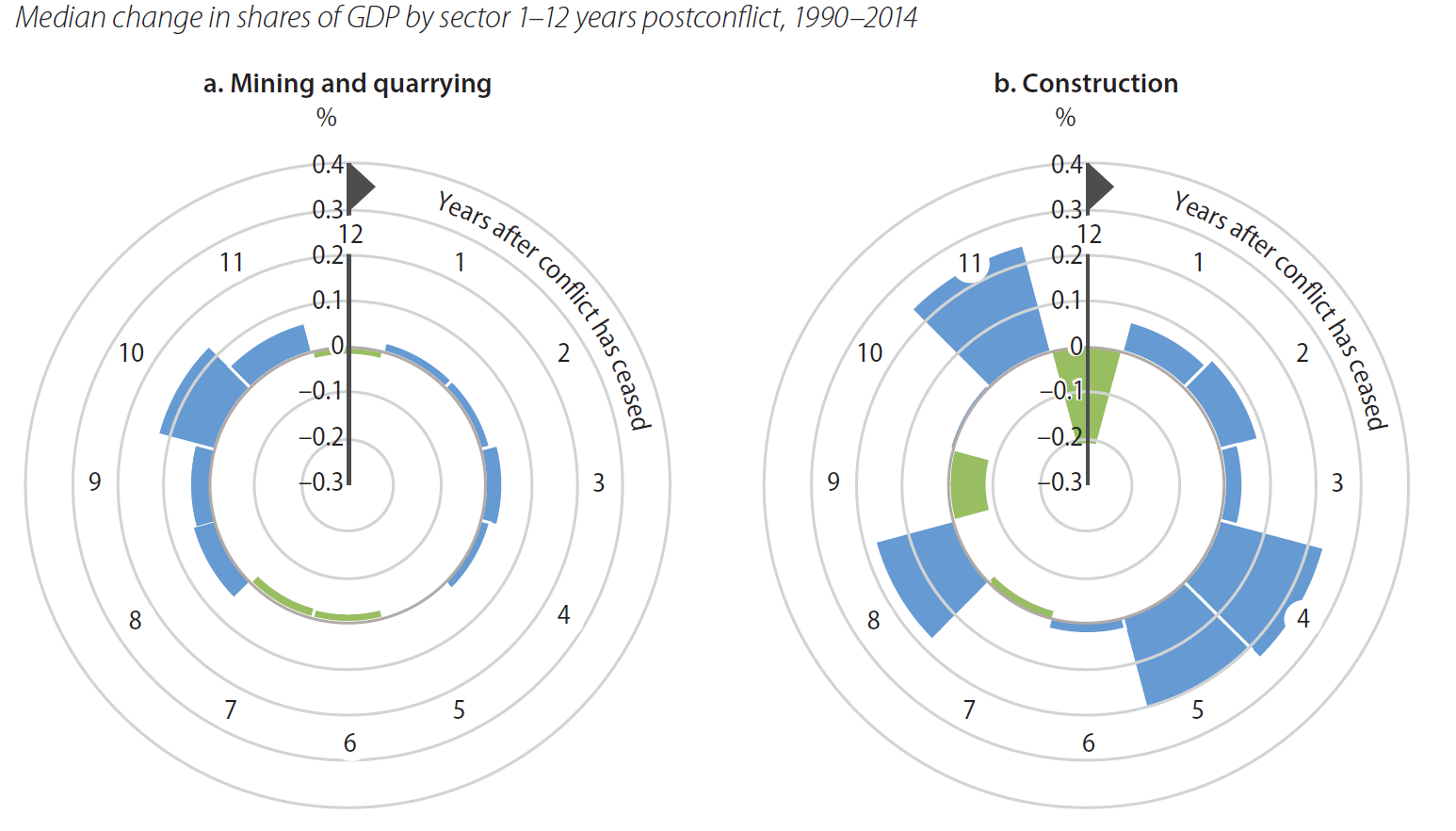

In addition, different sectors grow at different times in post-conflict situations during the process of reconstruction, and investment can be sequenced accordingly (see Figure 6). For instance, transportation, storage, and communications take off immediately after a conflict has ended, followed soon after by construction. These sectors also present real opportunities for foreign firms. Therefore, these sectors should be prioritised in FDI facilitation efforts in contexts of growing peace and stability. Manufacturing, in contrast, initially contracts and does not take off again for a long time, and so may not be the best choice for FDI facilitation.

Furthermore, there need not be generalised peace and stability across a country for pockets of geographies to be peaceful and stable, and FDI should be oriented to these areas, which can then have positive spillover effects on other areas, demonstrating the benefits of peace and stability to the economy (Ragousis and Shams, 2017) (cf. TIPS principle 7).

Finally, special economic zones can be oriented to helping successfully demobilise and reintegrate combatants by providing employment,[a] in what can be called ‘peace SEZs’, while the evidence shows that the presence of peacekeeping operations can significantly increase FDI in FCS countries (Jensen, 2020) (cf. TIPS principle 8).

Figure 6: ‘Growth clocks’— Growth of sectors after conflict has ceased (years vs percentage)

Source: Ragoussis and Shams 2018: 140-41

In this context, state-backed FDI may be needed to overcome the political, commercial, and security risk in post-conflict and conflict-affected environments. What has been called ‘state-backed macro-finance’ investment (Berdal and Mousavizadeh, 2010) helps mitigate these risks. These investments can especially be structured to support infrastructure, a much-needed base for the rest of the economy to pick up (cf. TIPS principle 9).

Many FCS countries also have large diasporas, that often left because of conflict. Diaspora investors understand their country of origin and have networks there, both of which can increase the chance of investment success. The presence of diaspora investors in their country of origin can also facilitate the internationalisation of firms from FCS countries, providing a secondary channel to generate revenue and growth (Nielsen and Riddle, 2009) (cf. TIPS principle 10).

The evidence also shows that multinational firms from the same region may be better placed to navigate the complexities of FCS environments in post-conflict situations, either through knowledge or networks. Past examples include FDI from Russia to Uzbekistan, Malaysia to Cambodia, South Africa to Nigeria, Japan and Thailand to Myanmar, and the UAE to Iraq (Ragoussis and Shams, 2018) (cf. TIPS principle 11).

Lastly, it may be wise to focus on partnering with local firms that have shown resilience and success in navigating the complexities of FCS environments, especially small and medium sized enterprises (SMEs) that may be exhibiting natural, organic growth, as in the context of fragility commerce needs to be built from the ground up, often starting with family-owned businesses (Berdal and Mousavizadeh, 2010) (cf. TIPS principle 12).

2. The G20’s Role

The G20 is uniquely suited to leverage trade and investment for peace and stability given that its members are both the largest sources and recipients of trade and investment flows, and certain members sit on the UN Security Council, which aims to defuse conflict. Overall, the group can play a critical role in determining the course of conflicts and, ideally, defuse them. In other words, the G20 is relevant on the economic and security levels to guiding and shaping global cooperation.

3. Recommendations to the G20

The recommendations below are set out in two pithy sections: TIPS principles that emerge from the evidence above, and TIPS measures to operationalise these principles.

12 principles to guide TIPS strategy and policy (‘TIPS principles’)

Trade

- Find balance between deepening trade relations and diversifying supply chains to grow resilience.

- Focus on promoting and facilitating trade from neighbouring countries.

- Pay special attention to relations between large trading partners, as these can have conflict even with significant trade relations.

- Ensure that trade regimes create free trade and do not favour special interests.

- Focus on promoting and facilitating trade in complements rather than trade in substitutes.

Investment

- Where natural resources are the main FDI opportunity, provide support but ensure proper guardrails through home-country due diligence requirements.

- Consider sequencing FDI support to specific zones of the country and specific sectors over time (especially with a view to providing employment for former combatants), informed through consultation with the private sector.

- Ensure SEZs help support peace and stability, and consider welcoming the presence of peacekeeping operations in the country.

- Consider using state financial and political support for FDI in post-conflict situations, especially focusing on infrastructure.

- Welcome and encourage diaspora investment, as well as the diaspora’s support with the internationalization of firms from post-conflict countries.

- Focus on promoting and facilitating FDI from the same region as these firms have familiarity and comfort operating in that environment.

- Consider partnering with resilient SMEs that have been able to survive/grow during conflict, especially family-owned business.

12 concrete and specific measures to operationalise TIPS in practice (‘TIPS measures’)

- Ensure tariffs and non-tariff barriers are low or removed on goods and services between neighbouring countries.

- Ensure FDI restrictions are low or removed on investments between neighbouring countries.

- Identify complementarities between neighbouring economies in terms of sectors and products, and use industrial policy to develop these sectors and products.

- Provide commitment to the liberalisation and facilitation of trade and investment between neighbouring economies in these priority sectors and products, with the aim of developing value chains criss-crossing across borders.

- Develop joint equity investment projects between firms in neighbouring countries.

- Develop a joint trade and investment committee to provide policy advocacy, co-chaired by representatives of two countries.

- Develop a business association co-chaired by representatives of two countries.

- Develop a jointly managed port or customs clearance system between two countries.

- Encourage manager swaps in firms from neighbouring countries.

- Allow government procurement access for firms from neighbouring countries.

- Create ‘peace SEZs’.

- Consider welcoming peacekeepers to maintain the peace.

Attribution: Matthew Stephenson, Jonathan Douw, and Peter Draper, “How Do Trade and Investment Contribute to Peace and Stability? What Should Policymakers Do?,” T20 Policy Brief, June 2023.

References

Berdal, Mats, and Nader Mousavizadeh. “Investing for peace: the private sector and the challenges of peacebuilding,” Survival 52, no. 2 (2010): 37-58.

Cheng, Evelyn. “Taiwan’s trade with China is far bigger than its trade with the U.S.,” CNBC, 22 August 2022.

Collier, Paul. The Bottom Billion: Why the Poorest Countries are Failing and What Can be Done About It, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007.

Draper, Peter, Andreas Freytag, Jena Naoise McDonagh and Matthias Menter. “The Political Economy of Due Diligence Legislation,” Institute for International Trade, The University of Adelaide, February 2023.

Gölgeci, Ismail, Harun Emre Yildiz and Ulf Andersson. “The rising tensions between efficiency and resilience in global value chains in the post-COVID-19 world,” Journal of Transnational Corporations, Volume 27, 2020, Number 2.

Government of Chinese Taipei, “Cross-Strait Relations”, retrieved 11 June 2023.

Hegre, Håvard, John R. Oneal, and Bruce Russett. “Trade does promote peace: New simultaneous estimates of the reciprocal effects of trade and conflict,” Journal of Peace Research, 47, no. 6 (2010): 763-774.

Jensen, Lars. Foreign Direct Investment and Growth in Fragile and Conflict-Affected Countries: The Role of Peacekeeping and Natural Resources, UNDP, 2020.

Kant, Immanuel. Perpetual Peace: A Philosophical Sketch, 1795

Keshk, Omar, Brian Pollins and Rafael Reuveny,. “Trade Still Follows the Flag: The Primacy of Politics in a Simultaneous Model of Interdependence and Armed Conflict”. Journal of Politics, 66, 2004.

Kim, Hyung Min and David L. Rousseau. “The Classical Liberals Were Half Right (or Half Wrong): New Tests of the ‘Liberal Peace’, 1960-88,” Journal of Peace Research, 42, no. 5 (2005): 523–43.

Lee, Jong-Wha and Ju Hyun Pyun. “Does Trade Integration Contribute to Peace,” ADB Working paper Series on Regional Economic Integration No. 24, Asian Development Bank, December 2008.

Martin, P., T. Mayer and M. Thoenig. “Make Trade not War?,”, Review of Economic Studies, 75, 2008, 865–900.

McDonald, Patrick J. “Peace through trade or free trade?” Journal of conflict resolution, 48, no. 4 (2004): 547-572.

Mill, John Stuart. Principles of Political Economy, London: Longmans, 1909

De Montesquieu, Charles. Montesquieu: The spirit of the laws, Cambridge University Press, 1989.

Nielsen, Tjai M., and Liesl Riddle. “Investing in peace: The motivational dynamics of diaspora investment in post-conflict economies,” Journal of Business Ethics, 89 (2009): 435-448.

Observatory of Economic Complexity (OEC), “China-India,” retrieved 28 May 2023.

Ragoussis, Alexandros and Heba Shams. “FDI in Fragile and Conflict-Affected Situations,” In Global Investment Competitiveness Report 2017/2018 (2018).

Reeves, Martin, Simon Levin, Sasi Desai, Kevin Whitaker. “Resilience vs. Efficiency: Calibrating the Tradeoff,” BCG Henderson Institute, 19 December 2020.

Reinsch, William Alan. “Resilience vs. Efficiency,” U.S. Center for Strategic and International Studies, 14 June 2021.

Schumpeter, Joseph. Sociology of Imperialism, 1919

Tagliapietra, Simone. “Economic Efficiency Versus Geopolitical Resilience: Strategic Autonomy’s Difficult Balancing Act,” Bruegel, 7 March 2023.

The Wire. “Despite Frosty Relations, India’s Trade with China Reaches Record Levels,” The Wire, 13 January 2023.

[a] Such an approach is currently being piloted in Ethiopia by the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development working with governmental authorities.