TF-6: Accelerating SDGs: Exploring New Pathways to the 2030 Agenda

The G20 can help steer the successful implementation of the newly agreed UN High Seas Treaty. However, given the current geopolitical landscape, lessons should be learned from past experiences of ‘securitisation’ of other ocean treaties. This is particularly important as the High Seas Treaty will impact other agreements that the G20 members are party to, including the Convention on Biological Diversity’s 30X30 target, regional ocean agreements, and the G7’s Ocean Deal.

Building on the lessons learnt from the global governance of the Southern Ocean, this policy brief explores governance of areas beyond national jurisdiction, against the contemporary geopolitical backdrop. We[a] recommend that the G20 support the High Seas Treaty by pushing for high environmental standards, reducing the space for ambiguity and securitisation by framing clear treaty texts, supporting the establishment of an empowered scientific and technical body, supporting ecosystem-based marine spatial planning, providing a forum for bilateral dialogues, and ensuring equity and representation in all negotiations.

1. The Challenge

The High Seas Treaty, also referred to as ‘the Paris Agreement for the Ocean’, is a historic step towards global ocean conservation. It has been hailed as a success for getting 193 countries onboard after 20 years of negotiations.

Over 70 percent of Earth’s surface is covered by the ocean. However, approximately two-thirds of that ocean cover lies outside of national jurisdictions. Like the waters of the ocean itself, species can cross boundaries between jurisdictions, which means that effective transboundary governance between and beyond areas lying under national jurisdictions is essential to safeguard marine biodiversity.

Our track record for such governance has been poor in many ways. Governance is, necessarily, a patchwork of local and regional issues, given that part of the global ocean is governed by national entities. However, while issues might seem local—such as illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing, the loss of habitats and biodiversity, lack of regional cooperation over the exploitation of marine resources—they can exacerbate or accelerate the pace of deterioration of our planet’s ocean. Likewise, ocean health is also threatened by global issues, such as climate change, marine litter, and pollution– all of which have local impacts.

Known as the high seas or areas beyond national jurisdiction (ABNJ),[b] the ‘common ocean’ is owned by all and therefore subject to the typical problems associated with the global commons.[c] While the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) has governed the global common ocean, covering issues such as shipping, some aspects of fishing, calculation of coastal states’ economic zones, and protection of the marine environment, it lacks the power and depth to address key issues in the ABNJ. With the absence of mechanisms or processes for conserving biodiversity, the ABNJ have become prime fishing grounds for nations whose fish stocks have begun to collapse in their own national jurisdictions. Global fish consumption continues to increase.[1] At the same time, only 8 percent of the ocean is covered by marine protected areas (MPAs), of which most can be found within national jurisdictions.

The newly agreed High Seas Treaty under UNCLOS could change this situation, but not without being ratified and effectively implemented. It addresses topics in four categories: (1) marine genetic resources, including questions on benefit-sharing, (2) area-based management tools, including MPAs, (3) environmental impact assessments (EIA), and (4) capacity-building and the transfer of marine technology.[2] It “shall be interpreted and applied in a manner that does not undermine relevant legal instruments and frameworks and relevant global, regional, subregional and sectoral bodies and that promotes coherence and coordination with those instruments, frameworks and bodies” (Article 4.2). The legal status of non-parties and the ‘relevant legal instruments’ remains unaffected by the Agreement.

The Treaty is expected to be the main mechanism for reaching the Convention on Biological Diversity’s (CBD) target to set aside 30 percent of the world’s marine areas by 2030 (30×30 target).[3] This target was developed in response to the failure to reach both the quantitative and qualitative target of 10 percent effective and representative protection outlined in SDG 14.5 and Aichi Target 11.[4] Reaching the new target will require effective, representative, and inclusive measures for marine conservation in the ABNJ.

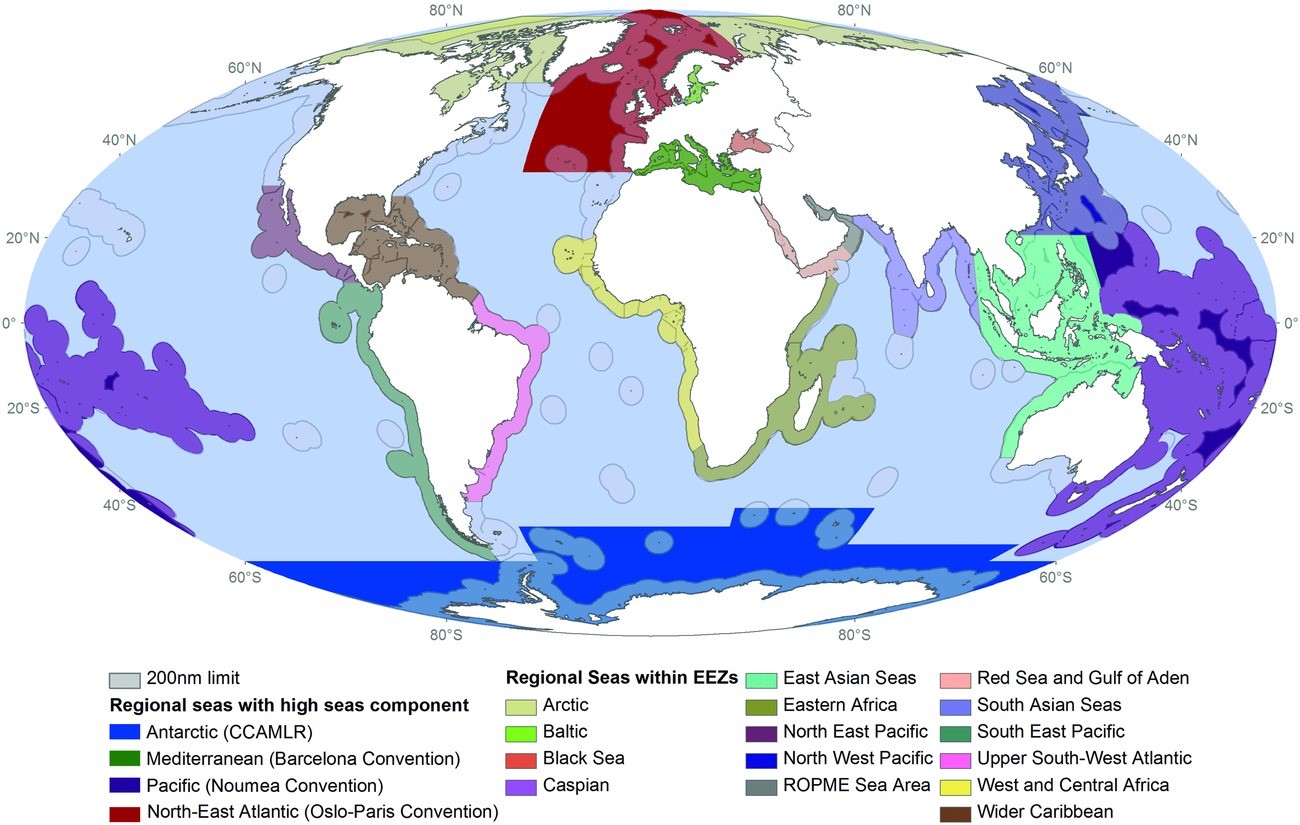

Currently, five Regional Seas Conventions cover parts of the ABNJ, including the OSPAR Convention, the Noumea Convention, the Convention on the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CAMLR Convention), the Barcelona Convention, and the Lima Convention.[5] These conventions provide regional institutional frameworks for a range of issues—not all regulate fisheries, for example.

Figure 1: Map showing regional seas organisations, with and without an ABNJ component

Source: Natalie C. Ban et al.[6]

Note: The Lima Convention is not included in the figure, but according to its Article 1, ABNJ within the area of the Lima Convention are included “up to a distance within which pollution of the high seas may affect that area.”[7]

Securitisation trends and their impact

Securitisation refers to the process of representing a political issue as an existential threat to stimulate and legitimise extraordinary measures beyond day-to-day politics.[8] Multiple actors with competing interests and an increasingly polarised world suggest a potential ‘securitisation’ of marine resources, where the ABNJ become the arena for extended geopolitics. This could seriously affect the implementation of the High Seas Treaty.

The trend towards securitisation of the maritime commons, particularly fisheries, seriously impacts international cooperation and increases the risk that other geopolitical issues play out in ocean negotiations.[9] As the hunt for fish stocks and rare minerals accelerates in the ABNJ, increased competition for resources could lead to territorial disputes and conflicts between countries and add tensions to an already rigid global geopolitical situation. Lessons from marine regions like the South China Sea show that securitisation can make it difficult to envisage effective engagement of UNCLOS.[10]

Despite the current geopolitical tensions, which we must account for in the immediate and near-term, the ramifications of how the new treaty is implemented will have environmental and political implications for decades to come. This brief presents some experiences from the ‘globally owned’ Antarctic region, which has had unique transboundary governance agreements for decades. The seemingly local and regional issues pertaining to the ocean link directly to global issues, all of which the G20 can tackle in ways we suggest at the end.

Uncertain impact of the High Seas Treaty

The new High Seas Treaty will be embedded in a regime complex, and require complex cross-instrument collaboration in order to effectively implement the treaty.[11] For example, an MPA designation under this agreement cannot undermine legal instruments such as regional fisheries management organisations, the International Seabed Authority, and the International Maritime Organization, which limits the treaty’s mandate to manage fisheries, mining, and shipping.

At the same time, the new instrument is seen as a possible way forward for aligning regulatory and governance approaches and to increase the protection of ocean species and ecosystems. To what extent this will be possible, however, will be highly dependent on states’ participation and commitment. For example, some states lean towards maintaining today’s status quo because increased conservation may conflict with their commercial interests.[12] The caveats of the treaty reflect the struggles that have historically caused tensions in the governance of the Southern Ocean.

Learning from Antarctic governance

The CAMLR Convention provides a legally binding framework for member states, freezes territorial claims in the area, and is an integral part of the Antarctic Treaty System. The commission that governs under the Convention on the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCAMLR) was founded on the principles of peaceful use, freedom of scientific research, and cooperation. Mining is banned under the Antarctic Treaty Environment Protocol,[13] which also manages other commercial activities such as tourism.

CCAMLR is a frontrunner when it comes to conservation, including ‘rational use’, of the Southern Ocean and its marine living resources. Despite a pioneering approach that is precautionary and ecosystem-based,[14] CCAMLR is dealing with issues where science is used to protect political interests, rather than underpinning beneficial policy for marine environments, and where reliance on consensus-based decision making is used as a veto. This has made reaching consensus on proposals related to broader conservation very challenging,[15] resulting in it being too slow to address the impact of climate change on the Southern Ocean’s marine ecosystem.[16]

Existing adopted and proposed MPAs do not properly represent all conservation features, and achieving representative protection of the area is dependent on political will.[17] Indeed, engagement from external political leaders from the US and Russia was required for the latest MPA adoption in the region, the Ross Sea Region MPA.[18]

We highlight three examples where securitisation of CCAMLR has had implications for the negotiations. These illustrate the interplay between the quest for national security versus the overall governance of a common resource and highlight how individual stakeholders can shape outcomes.

Example 1. Failure to reach consensus: While proposals for three new MPAs have been approved by the Scientific Committee of CCAMLR, and most members have agreed on their adoption, Russia and China have opposed the adoption. They have demanded that proponents justify the need for the MPA establishment, arguing that there isn’t sufficient scientific evidence.[19] To address this impasse, it was agreed during the 41st CCAMLR meeting to hold an extraordinary meeting in 2023 to discuss spatial planning and MPAs.[20]

Example 2. Different interpretations: The objective of the CAMLR Convention has been repeatedly clarified to be conservation,[21] while allowing for rational use if it follows the principles of conservation (Article II.3). However, some member states interpret ‘rational use’ as ‘the right to fish’.[22],[23] This has contributed to a polarisation between states with fisheries interests and those mainly supporting conservation for the good of the commons or other reasons.

Example 3. Sovereignty and the knock-on effects from one individual stakeholder’s actions: Proposals most likely to reach consensus in CCAMLR have generally been related to fisheries management,[24] but the misuse of the consensus-based decision-making process has increasingly affected fisheries’ management as well. For example, in 2021, during the 40th meeting of CCAMLR, Russia vetoed the renewal of an existing conservation measure on the fishing of Patagonian toothfish in Subarea 48.3, even though the renewal was supported by the Scientific Committee of CCAMLR.[25] This controversial and arguably political blockage[26] disturbed the status quo of CCAMLR, by opening the longstanding sovereignty dispute over the Falklands/Malvinas, the South Georgia Islands, and the South Sandwich Islands between Argentina and the UK.

Over the past 40 years, CCAMLR has been able to avoid this confrontation. However, the recent blockage opened the issue of different interpretations of the so-called ‘Chairman’s statement’, which allows member states to use national law for fishing within their national jurisdiction. At issue is how the Chairman’s statement applies to a member state’s–in this case the UK’s–right to use national law to allow fishing activities in waters that are surrounding islands under territorial dispute. This creates unprecedented challenges for CCAMLR, as the issue also involves third parties’ interests and could affect the functioning of the CCAMLR itself.[27]

Much can be learned from experiences in Antarctic governance and its history of working together to preserve the continent and its surrounding waters. This has manifested itself e.g., in the banning of mining and the adoption of the Ross Sea Region MPA. Although a ban on mining is not on the agenda for the new High Seas Treaty, the commitment to ocean conservation initiatives and collaboration to implement such major measures is something that can be learned from the Antarctic experience.

Simultaneously, there are also lessons to be learned from the recent increase in polarisation and securitisation in, for example, CCAMLR where consensus-driven decision-making and the argument of insufficient scientific evidence are used to oppose implementation of conservation measures. Although the High Seas Treaty will not face the same problem of individual states being able to block MPAs, as it has a voting system that can be used when all attempts to reach consensus have been exhausted, a robust treaty still relies on the participation and commitment of all member states to ensure effective implementation and continued monitoring of adopted measures.

2. The G20’s Role

The G7’s Ocean Deal reinforces two key commitments towards ocean action. First, it highlights support for enhanced global ocean governance that is built on the framework established under the UNCLOS. The G7 will have to address the ABNJ as part of their commitment to the development of robust and successful ocean governance. Second, it highlights G7’s commitments to deliver on concrete ocean action within the G7 and beyond, including the 30 percent of coastal and marine areas.[28]

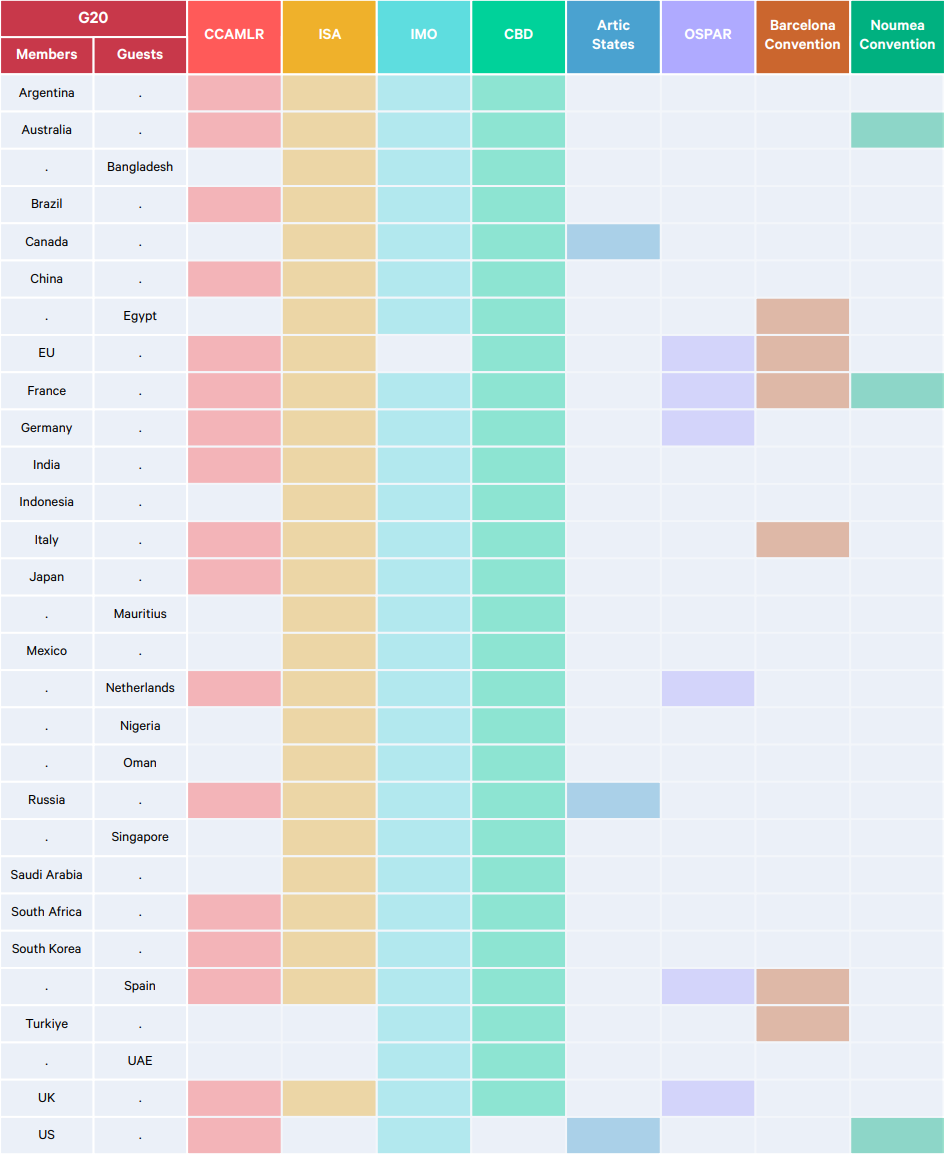

As the High Seas Treaty does not have the mandate to undermine other instruments, collaborations between the different instruments will be necessary to ensure effective protection in line with the 30×30 target. The G20 has a significant role to play here. For example, 15 of its 20 members are also members of the CCAMLR. ‘Figure 2’ highlights the G20 members’ overlap with other governance instruments.

India has many opportunities to safeguard ocean biodiversity given both its long coastline, and its commitments to global goals such as the 30×30 target. India, for example, can positively impact ocean health by adopting an ecosystem-based approach that incorporates the links between land, coastlines, and the ocean for dealing with marine pollution. Additionally, India can promote a smooth ratification of the High Seas Treaty and support peaceful transboundary governance and management of the ocean at platforms such as CCAMLR and the Indian Ocean Rim Association.

Figure 2: The G20 members’ overlap with other ocean related governance instruments.

Note: Illustration of G20 members and guest countries that are also members to a selection of other relevant instruments including the CCAMLR, ISA, IMO, CBD, the Arctic Council, OSPAR, the Barcelona Convention, and the Noumea Convention.

Source: Authors’ own, based on data collected on 30 March 2023.[29],[30],[31],[32],[33],[34],[35],[36]

3. Recommendations to the G20

The G20 has an opportunity to drive the successful ratification and implementation of the new High Seas Treaty, as well as shift the framing of other treaties to lead to a more successful global management of the ocean that is commonly held, outside the borders of any national or regional entity. We see the following options, for research, policy, and partnership building, falling within the scope of the commitments already made by G7 countries.[37]

Facilitate ocean governance by providing environmental policy recommendations to the member states and advancing the best available scientific research on the ocean:

- Provide clear guidance to parties: The G20 can help support high environmental standards in sectors that impact the ABNJ. The areas excluded from the scope of the High Seas Treaty, e.g., existing bodies already responsible for regulating activities such as fisheries, shipping, and deep-sea mining, should have at the very least, the same standards for EIAs as the High Seas Treaty recommends. The G20 should also push for clear treaty text and legal documents, as clear formulations can minimise divergence between stakeholder interpretations, as experienced in the CCAMLR, described above.

- Scientific support: We recommend an empowered scientific and technical body in the High Seas Treaty that can support countries to propose areas for protection and work towards reaching the 30×30 target. Since the Treaty is about conservation and sustainable use, the G20 could help regions navigate the benefits and limitations that arise from the application of these concepts. Further, the G20 can help regions make an informed assessment of their suitability based on today’s best available science. Lack of data in the ABNJ, and more specifically, the uneven distribution of existing data between the global North and South needs to be addressed. The G20 can contribute to data collection required to underpin and facilitate comprehensive EIAs. The G20 can also promote a science- and ecosystem-based (precautionary) approach. Given the lessons learned from CCAMLR, lack of data for an EIA should not be used as an excuse to underpin policy that protects states’ own interests and hinders the implementation of area-based management tools, for which the G20 can advocate.

Deliver on concrete ocean action by promoting successful holistic outcomes and strengthening collaboration:

- Promote an ecosystem-based approach: The G20 should promote and adopt a holistic approach, incorporating the links between land, coastlines, and the ocean. Ecosystems do not respect geopolitical boundaries, nor do they consider state governance or management in their behaviour. Therefore, the G20 must ensure that protection is ecosystem-based, e.g., considering species migration and how actions on land can affect marine ecosystems and vice versa. Adaptive management should be incorporated in protective measures. With respect to the ABNJ, the G20 can raise awareness about the importance of and support the development of proposals of representative and interconnected area-based management tools. It is key that the G20 focus not only on quantity, but also on the quality of these tools (whether they are comprehensive and representative, whether those implemented are networked in line with the CBD targets).

- Strengthen collaboration: The G20, as a strong partnership, can contribute to a smoother ratification of the High Seas Treaty and support the first Conference of Parties to ensure that it is a successful meeting, given that ocean health is under threat and only a few years remain to reach the 30×30 target. The G20 can engage in ocean matters at the highest levels, much like it did during the discussions regarding the implementation of the Ross Sea MPA in the Southern Ocean. Geopolitical tensions spill over, and the G20 can provide a forum for creating bilateral dialogues.

- Support the Global South in taking the lead: The Global South led the way in ensuring that the High Seas Treaty embraces principles of equity, fair sharing of benefits, and adopts a precautionary approach. However, the modalities for the implementation of these principles such as, the sharing of monetary benefits from the utilisation of marine genetic resources, will be decided on during the first Conference of the Parties. The G20 and India can play an important role in supporting the Global South to take the lead once again in ensuring that the suggested committee for access and benefit-sharing is representative of the signatories, including geography, economies, and gender.

Attribution: Elin Leander et al., “High Seas Treaty: Searching for Common Grounds,” T20 Policy Brief, June 2023.

[a] This publication is a deliverable of MISTRA GEOPOLITICS, which is funded by MISTRA – the Swedish Foundation for Strategic Environmental Research.

[b] “Areas beyond national jurisdiction (ABNJ) are those areas for which no nation has sole responsibility for management. They comprise the high seas; the seabed beyond the limits of the continental shelf; polar areas; and outer space”.

[c] ‘Global commons’ refers to shared natural resources and systems that are not owned by any individual or nation but are instead the responsibility of the international community as a whole. These resources include the ocean, atmosphere, outer space, and Antarctica, as well as certain areas of the internet, genetic information and cultural heritage.

[1] Food and Agriculture Organization, “The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2022: Towards Blue Transformation,” Rome, FAO, 2022.

[2] Rachel Tiller et al., “Shake It Off: Negotiations Suspended, but Hope Simmering, after a Lack of Consensus at the Fifth Intergovernmental Conference on Biodiversity beyond National Jurisdiction,” Marine Policy 148 (February 1, 2023): 105457.

[3] Convention on Biological Diversity.

[4] UN Environment Programme World Conservation Monitoring Centre and International Union for Conservation of Nature, “Protected Planet Report 2020“, Cambridge, UNEP-WCMC and IUCN, 2021.

[5] “Conservation of Biodiversity in Areas beyond National Jurisdiction (BBNJ),” UN Environment Programme, accessed December 6, 2022.

[6] Natalie C. Ban et al., “Systematic Conservation Planning: A Better Recipe for Managing the High Seas for Biodiversity Conservation and Sustainable Use,” Conservation Letters 7, no. 1 (2014): 41–54.

[7] UN Environment, Regional Seas Programmes Covering Areas Beyond National Jurisdictions, 2017.

[8] Barry Buzan, Ole Wæver, and Jaap de Wilde, Security: A New Framework for Analysis (Lynne Rienner Publishers, 1998).

[9] Guoqiang Luo and Zhixin Chi, “Conflicts and Challenges of Sustainable Fisheries Governance Cooperation under the Securitization of the Maritime Commons,” Fishes 8, no. 1 (January 2023): 1.

[10] Christo Odeyemi, “UNCLOS and Maritime Security: The ‘Securitisation’ of the South China Sea Disputes,” Defense and Security Analysis 31, no. 4 (October 2, 2015): 293–302.

[11] Arne Langlet and Alice B. M. Vadrot, “Not ‘Undermining’ Who? Unpacking the Emerging BBNJ Regime Complex,” Marine Policy 147 (January 1, 2023): 105372.

[12] Amy Hammond and Peter JS Jones, “Protecting the ‘Blue Heart of the Planet’: Strengthening the Governance Framework for Marine Protected Areas beyond National Jurisdiction,” Marine Policy 127 (May 1, 2021): 104260.

[13] “Environmental Protocol | Antarctic Treaty,” ATS, accessed June 19, 2023.

[14] Marcus Haward, “Biodiversity in Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction (BBNJ): The Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCAMLR) and the United Nations BBNJ Agreement,” The Polar Journal 11, no. 2 (July 3, 2021): 303–16.

[15] Lyn Goldsworthy, “Consensus Decision-Making in CCAMLR: Achilles’ Heel or Fundamental to Its Success?,” International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law and Economics, (April 7, 2022).

[16] Steven L Chown et al., Antarctic Climate Change and the Environment: A Decadal Synopsis and Recommendations for Action, Cambridge, Scientific Committee on Antarctic Research, 2022, www.scar.org.

[17] Anne Boothroyd et al., “Benefits and Risks of Incremental Protected Area Planning in the Southern Ocean,” Nature Sustainability, (March 6, 2023), 1–10.

[18] Seth Sykora-Bodie and Tiffany Morrison, “Drivers of Consensus‐based Decision‐making in International Environmental Regimes: Lessons from the Southern Ocean,” Aquatic Conservation Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems 8 (September 9, 2019): 311–25.

[19] Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources, “Report of the Forty-First Meeting of the Commission,” Hobart, CCAMLR, 2022, para. 5.13, 5.15, 5.27.

[20] CCAMLR, “Report of the Forty-First Meeting of the Commission”

[21] Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources, “Report of the Thirty-First Meeting of the Commission,” Hobart, CCAMLR, 2012, para. 9.17.

[22] Jennifer Jacquet et al., “‘Rational Use’ in Antarctic Waters,” Marine Policy 63 (January 1, 2016): 28–34.

[23] Sykora-Bodie and Morrison, “Drivers of Consensus‐based Decision‐making in International Environmental Regimes.”

[24] Goldsworthy, “Consensus Decision-Making in CCAMLR.”

[25] Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources, “Report of the Fortieth Meeting of the Commission,” Online, CCAMLR, 2021.

[26] CCAMLR, “Report of the Forty-First Meeting of the Commission,” para. 4.36.

[27] Bruno Arpi and Jeffrey McGee, “Fishing around the South Georgia Islands and the ‘Question of the Falklands/Malvinas’: Unprecedented Challenges for the Antarctic Treaty System,” Marine Policy 143 (September 2022): 105201.

[28] G7, “G7 Ocean Deal,” Berlin, G7, 2022.

[29] “Members | CCAMLR,” Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources, accessed March 30, 2023.

[30] “Member States – International Seabed Authority,” International Seabed Authority, accessed March 30, 2023.

[31] “Member States,” International Maritime Organization, accessed March 30, 2023.

[32] “List of Parties,” Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity, accessed March 30, 2023.

[33] “The Arctic Council,” Arctic Council, accessed March 30, 2023.

[34] “Contracting Parties,” OSPAR Commission, accessed March 30, 2023.

[35] “Contracting Parties | UNEPMAP,” UN Environment Programme, accessed March 30, 2023.

[36] “Noumea Convention | Pacific Environment,” South Pacific Regional Environment Programme, accessed March 30, 2023.

[37] G7, “G7 Ocean Deal”