Introduction

Among the declarations that the G20 made in 2017 was to eradicate modern-day slavery. The grouping emphasised the need for immediate and effective measures to eliminate child labour, forced labour, human trafficking, and all forms of modern-day slavery by 2025. Such an aim will help fulfil Goal 8.7 of the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which calls for the eradication of forced labour, modern slavery, and human trafficking by 2030.

The trafficking of women and children violates their basic human rights. Yet this crime remains one of the least understood forms of transnational crime, with significant gaps existing in both data on its incidence, and the legislative measures that countries have implemented to respond to the challenge.

This Policy Brief assesses the current situation of trafficked women in India and its adjacent countries in Southeast Asia. It offers an understanding of trafficking in women in South and Southeast Asia, and outlines policy recommendations for finding sustainable solutions to help survivors of trafficking in South and Southeast Asia resume their lives.

The Challenge

Incidents of human trafficking are underreported, resulting in a lack of comprehensive understanding of its reach and scale. In both South and Southeast Asia, human trafficking thrives for multiple reasons (see Box 1).

Box 1:

Source: TIP 2022 report

Most trafficked individuals are low-skilled, domestic helpers, sex workers, or sweatshop employees. In this context, it is noteworthy that migration within and outside these regions has been feminised because of the increasing demand for domestic and care jobs in Asia and beyond. In most cases, these women make up the majority of workers in the vulnerable and largely informal sectors of domestic work, hospitality, and sex work.

Eastern South Asia

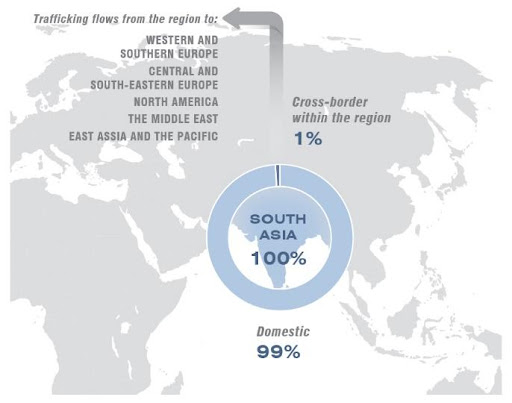

A significant proportion of human trafficking takes place in South Asia, with victims from this region being recorded in over 40 countries across the world. The destination countries include those in the Gulf region, as well as Western and Southern Europe and North America; a smaller number are taken to countries in Southeast Asia and Africa (see Map 1).

Map 1: Trafficking Routes in South Asia

Source: UNODC 2022

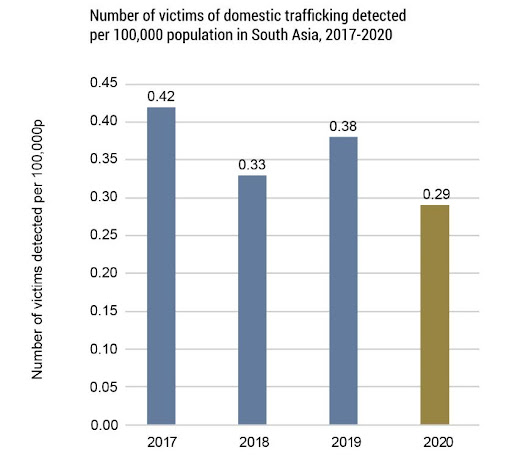

Obtaining accurate statistics on the number of women who fall victim to trafficking is a massive challenge. However, recent reports from government entities, NGOs, and the media suggest that trafficking within and outside of South Asia is on the rise. Figure 1 shows the domestic trafficking trends in the region. Adding to the complexity of trying to address the issue of human trafficking in South Asia, is the absence of universal regulations.

Figure 1: Domestic Trafficking Trends in South Asia

Source: UNODC 2022

Table 1 gives a snapshot of the situation in the eastern part of South Asia— comprising India, Bangladesh, and Nepal—the hub of human trafficking in the region. Table 2 lists the border points through which human trafficking takes place in the region.

Table 1: Human Trafficking in Eastern South Asia (2020)

| Country | Reported Cases of Trafficking | Victims’ Profile |

| India | Labour trafficking (5,156);

Bonded labour (2,837); Sex trafficking (1,466); Potential trafficking victims (694) |

53 percent – adults;

59 percent – female;* 41 percent – male; 47 percent – children |

| Nepal | Sex trafficking (99)

Labour trafficking (64) Unspecified exploitation (24) |

107 adults (183 female; 4 male);

80 children |

| Bangladesh | Sex trafficking (580);

Labour trafficking (6,378); Unspecified (717) |

Sex trafficking victims:

Women: 429; Men: 10; Children: 120; 20 LGBTQI+ individuals; Labour trafficking victims: Men – 4,328; Women – 1,902; Children – 132; 14 LGBTQI+ individuals. |

Source: Authors’ own, based on the TIP 2022 report

*Note: The category ‘Female’ encompasses both female children and adult women; ‘Women’ refers to adult women; and ‘Children/Girls/Boys’ refers to children below 18 years.

Table 2: Corridors of Human Trafficking in Eastern South Asia

| Corridors of Trafficking | Locations |

| India – Bangladesh | Darshana (Bangladesh) – Gede (India);

Banglabandha (Bangladesh) – Phulbari (India); Burimari (Bangladesh) – Chengrabanda (India); Benapole (Bangladesh) – Petrapole (India) |

| India – Nepal | Nepal – Kakarbhitta, Biratnagar, Bhantabari, Birgunj, Bhairawa, Nepalgunj, Mahendra Nagar;

India – Raxual , Kishanganj, Maharajgunj, Rupaidiha |

Southeast Asia

Southeast Asia has known links with networks of global trafficking, particularly for sex. More than 85 percent of victims of human trafficking in the region come from Indonesia, the Lao People’s Democratic Republic, the Philippines, Myanmar, Cambodia, and Vietnam. Most of the women are engaged in the vulnerable and largely informal sectors of domestic work and hospitality, and the sex industry.

Cambodia, the Lao PDR, Myanmar, Thailand, and Vietnam are the hubs of human trafficking in Southeast Asia. Some countries in the region are part of the route taken by criminal elements for the smuggling of migrants, either as source, transit, or destination country. Table 3 shows the corridors of trafficking in Southeast Asia.

Table 3: Corridors of Human Trafficking in Southeast Asia

| Corridors of Trafficking | Locations |

| Cambodia-Thailand | Myanmar- Cambodia- Laos

(source, destination, and transit point) |

| . Myanmar-Thailand | origin and transit |

| Indonesia-Malaysia | Malaysia – transit and destination country |

| Vietnam-Thailand-China | Vietnam – source and transit country |

| Laos-Thailand | Laos – source and transit country |

Table 4: Human Trafficking in Southeast Asia: A Snapshot

| Country | Reported cases of trafficking (2020, 2021) | Victims’ profile |

| Cambodia | 270 – Forced Marriage;

43 – Forced Labour; <5 – Sexual Exploitation |

17 % – Women;*

15 % – Men; 40 % – Female; 42% – Boys |

| Myanmar | 150 – Sexual Exploitation;

<5 – Forced Labour; <5 – Other forms of trafficking |

130 – Women;

15 – Men; 39 – Girls |

| Thailand | 414 – Trafficking victims;

181 – Sex trafficking; 233 – Labour trafficking |

151 – Males;

263 – Females; 72 – Children; (Out of 414: 312 – Thai; 94 – Myanmarese; 2 – Laotian; 6 from unspecified countries) |

| Philippines | 1,802 Victims:

535 – Sex trafficking; 501 – Forced labour; 766 – Unspecified |

551 – Male;

1251 – Female |

*Note: The category ‘Female’ encompasses both female children and adult women; ‘Women’ refers to adult women; and ‘Children/Girls/Boys’ refers to children below 18 years.

Source: Authors’ own

Empowering Survivors

Skill Development

To prevent re-victimisation and promote sustainable reintegration, rehabilitation assistance in the form of skills training programs is crucial. For transnational survivors, skill development initiatives remain a temporary option while awaiting repatriation to their country of origin. Programs for skill development can help victims of human trafficking acquire the skills and knowledge necessary to find employment, or start their own small-scale income-generating livelihood.

The provision of skills training, however, is not an easy task as survivors have to deal with the physical and psychological trauma of their ordeal that may hinder their ability to acquire new skills. Programs for skill development should be tailored to the needs and abilities of the survivor. Many of them might require basic literacy and numeracy skills, to begin with.

Livelihood Opportunities

Livelihood training is a rehabilitative tool for rescued survivors of commercial sexual exploitation. Tables 5 and 6 summarise initiatives by governments and non-government organisations in South and Southeast Asia.

Table 5: Skill Development Initiatives in South Asia (East)

| Country | Government and Non-Government Schemes |

| India |

|

| Bangladesh |

|

| Nepal |

|

Table 6: Skill Development Initiatives in Southeast Asia

| Country | Government and Non-Government Schemes |

| Thailand |

|

| Indonesia |

|

| Malaysia |

|

| Cambodia |

|

Gaps in Implementation

Skill development programs help empower survivors of human trafficking, providing them with opportunities to regain their dignity, earn some income, build their confidence and live independently. Despite the benefits of these programs, however, interviews conducted by these authors and literature reviews have revealed some gaps that need to be addressed by the G20.

Lack of agency: The journey towards recovery and social reintegration is impeded by numerous obstacles, and the absence of a standardised rehabilitation policy for all survivors exacerbates the situation. The implementation of current rehabilitation policies, such as the Ujjwala Scheme in India that focuses on reintegrating victims of commercial sexual exploitation and trafficking, is unclear, and there are no audits conducted on shelter homes or reintegrated survivors. This is the case with Bangladesh and Nepal as well.

Lack of continued support: Survivors of human trafficking face challenges when returning to their home communities after spending years under the control of traffickers and in shelter homes. The lack of supporting documents and immediate financial assistance makes it challenging for survivors to rebuild their lives with dignity, and they become vulnerable to poverty and re-trafficking. Moreover, the stigma of trafficking exacerbates their difficulties as they are discouraged from continuing their education, acquiring skills, and pursuing employment opportunities.

Lack of education: While there are education programs accessible for survivors of human trafficking, there is a lack of access to education beyond basic numeracy and literacy skills.

Absence of sustainable income: Although vocational programs are beneficial for survivors to earn a minimal income, they may not provide a sustainable source of income to support an independent life unless appropriately linked to a market.

Institutional limitations: Organisations working with trafficking survivors note that it is difficult to come up with innovative livelihood models as the existing ones are limited by their internal capacities and capabilities. Systematic funding remains a hurdle for ensuring the continuity of programs.

The Role of the G20

In 2017, the G20 nations made a commitment to promoting human rights diligence in corporate supply chains and are currently developing policy frameworks to effectively eradicate human trafficking. Employment and skill development have consistently been key priorities for the G20. While the initial G20 summit in Washington DC (2008) focused on the global financial crisis, leaders recognised the significance of employment in achieving a smooth and sustained recovery during the second summit in London in April 2009. Since then, employment and skills have been on the agenda of nearly all G20 presidencies. Strong skills systems are fundamental to the prosperity of communities and societies. In developing and emerging G20 economies, which have relatively young populations, skills are vital for harnessing the demographic dividend.

The G20 Training Strategy and Skill Up program aims to enhance the relevance of education and training outcomes to meet labour market demands and improve the employability of both men and women. In this regard, it is important to include survivors of trafficking in the talent pool. G20 countries have a responsibility to address the challenges faced by women migrant workers and reduce their vulnerability to forced labour and human trafficking. Even as they are actively working on policy frameworks to effectively combat human trafficking, a comprehensive understanding of the South and South East Asian context is required to implement inclusive measures.

Recommendations to the G20

Skilling is crucial particularly for emerging economies with young populations, as it can drive economic growth. Including survivors of trafficking in this talent pool would not only provide them with viable employment opportunities but also contribute to their financial empowerment. By involving trafficked survivors in the workforce, G20 countries can enhance women’s labour market security and improve employment conditions. The G20 has the potential to contribute to the formulation of better policy frameworks that address the needs of women in South and Southeast Asia, ensuring their protection, promoting their rights, and fostering gender inclusivity.

Giving survivors agency: It is essential to provide survivors of trafficking with the freedom to choose their desired vocation for training instead of being limited to a predefined set of skills mandated by programs created by government. Income-generating activities and micro-enterprise awards, combined with other reintegration components—such as psychological assistance and vocational training—can be an effective way of increasing the independence, self-sufficiency, and self-esteem of survivors when they are particularly entrepreneurial.

Lessons may be gleaned from the experience of the United Kingdom (UK), where the government has taken an initiative called the National Referral Mechanism (NRM) which engages directly with survivors and seeks their inputs in creating an inspection regime for support services. The International Survivors of Trafficking Advisory Council (ISTAC), launched in 2021, consists of 21 trafficking survivor leaders from across the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) offering advice, guidance, and recommendations on combating human trafficking.

Similarly, the United States Advisory Council on Human Trafficking established in 2015 provides human trafficking survivors with a platform to offer insights, advice, and recommendations on federal policies and initiatives related to combating human trafficking. For its part, the Inter-Agency Council Against Trafficking in the Philippines, a few years ago conducted virtual focus group discussions with survivors of trafficking to gather feedback on the quality of protection services, case management, and the difficulties encountered in providing such services.

Certification of skilling programs: The state government/local government should be proactive in establishing certified vocational training centres that have robust marketing links and placement opportunities to provide community-led livelihood skills. For example, the Vipla Foundation in India collaborates with technical organisations to facilitate the training of trafficked survivors, after which they are granted certification.

Sustained initiatives for skill development: Most programs on skill development are short-term and unsustainable, leaving victims without continued care after the program’s completion. While microfinance projects exist to assist victims in launching their own income-generating livelihood, there is a dearth of prolonged assistance for entrepreneurship. It is possible that the survivors end up still lacking the information and skills essential to operate and expand their enterprises.

Educational support: There should be more schools that charge lower tuition fees, if at all, so that survivors of trafficking can continue their education. Organisations in collaboration with national and local governments can help them reintegrate into the educational system by providing them financial and other assistance. Children of sex trafficking survivors can also be provided assistance so they can attend school.

Awareness generation: Knowledge building alone has not prevented migration-related exploitation or trafficking in parts of South and South East Asia. Individual-level interventions to increase knowledge, sense of empowerment, and awareness of rights will have little effect without interventions that address other trafficking-related inequalities—for instance, opportunities for better employment.

Funding: A special fund allocation in the government’s budget that caters to survivors of all types of trafficking must be created. Systematic funding will be important to ensure the continuity of current programs.

Market opportunities: There is a need for the creation of stable and systematic markets for products made by survivors of trafficking. In Nepal, for example, clothing companies Elegantees and Mulxify support trafficking survivors and those at-risk of trafficking, to engage them in creating handcrafted clothing, jewellery, and accessories. Jewellery-making company, Purpose Jewellery, through its non-profit institution, International Sanctuary, provides holistic care and job opportunities for women escaping human trafficking in California and Mumbai. Sari Bari is another institution dedicated to assisting sex-trafficking survivors in Kolkata; they are taught skills in making bags, home decorations, and baby products out of second-hand saris. Program implementers must raise awareness about such programs.

Endnotes

1 “G20 Leaders ́ Declaration: Shaping an interconnected world”, Press Corner, July 8, 2017,

https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/STATEMENT_17_1960

2 Anwar Iqbal, “UN sees South Asian women as most vulnerable to human trafficking”, Dawn, January 28,

2023, https://www.dawn.com/news/1734014; Donahue, Steven, Michael Schwien, and Danielle LaVallee.

“Educating emergency department staff on the identification and treatment of human trafficking

victims.” Journal of emergency nursing 45, no. 1 (2019): 16-23.

3 AKM Ahsan Ullah,et. al.. “Globalization and Migration: The Great Gender Equalizer?.” Journal of

International Women’s Studies 25, no. 3 (2023): 2.

4 . Ullah, et al. “Globalization”

5 Global Report on Trafficking in persons 2022, United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), 2022,

https://www.unodc.org/documents/data-and-analysis/glotip/2022/GLOTiP_2022_web.pdf

6 “2022 Trafficking in Persons Report: India”, U.S. Department of State, 2022,

https://www.state.gov/reports/2022-trafficking-in-persons-report/india/

7 “2022 Trafficking in Persons Report: Nepal”, U.S. Department of State, 2022,

https://www.state.gov/reports/2022-trafficking-in-persons-report/nepal/

8 “2022 Trafficking in Persons Report: Bangladesh”, U.S. Department of State, 2022,

https://www.state.gov/reports/2022-trafficking-in-persons-report/bangladesh/

9 Interview with the Officials, the Directorate of Child Rights and Trafficking, Government of West Bengal, by

Anasua Basu Ray Chaudhury, Kolkata, 5 April 2021.

10 Interview with Chandra Kishore, Journalist, on Human trafficking in Nepal and India border and Nepal

conditions by Anasua Basu Ray Chaudhury, Birgunj, 2015

11 AKM Ahsan Ullah and Mallik Akram Hossain. “Gendering cross-border networks in the greater Mekong

subregion: Drawing invisible routes to Thailand”, Advances in Southeast Asian Studies 4, no. 2 (2011):

273-289.

12 Ullah and Hossain. “Gendering,” 273-289.

13 IOM UN Migration, “Covid-19”

14 Ullah and Hossain. “Gendering,” 273-289.

15 Ullah and Hossain. “Gendering,” 273-289.

16 East Asia – Pacific, UNODC 2022, https://www.unodc.org/documents/data-and-

analysis/glotip/2022/East_Asia_and_the_Pacific.pdf

17 UNODC 2022, East Asia – Pacific

18 “2022 Trafficking in Persons Report: Thailand”, US State Department, 2022,

https://www.state.gov/reports/2022-trafficking-in-persons-

report/thailand/#:~:text=The%20414%20trafficking%20victims%20identified,233%20victims%20of%20labor

%20trafficking.

19 “2022 Trafficking in Persons Report: Philippines”, US State Department, 2022,

https://www.state.gov/reports/2022-trafficking-in-persons-

report/philippines__trashed/#:~:text=The%20government%20reported%20identifying%201%2C802,male%20

and%201%2C251%20were%20female.

20 Tsai Cordisco, et. al. “Perspectives of survivors of human trafficking and sexual exploitation on their

relationships with shelter staff: Findings from a longitudinal study in Cambodia,” The British Journal of Social

Work 50, no. 1 (2020): 176-194.

21 U.S. Department of State, “2022 Trafficking in Persons Report: India”

22 Rescue Foundation, https://rescuefoundation.net/project/art-and-craft/ accessed on 27 March 2023

23 Prerna Anti Trafficking, https://www.preranaantitrafficking.org/ accessed on 27 March 2023

24 Jabala Action Research Organisation, http://www.jabala.org/# accessed on 27 March 2023

25 Anindita Shome, “Hon’ble President launches a pre-skilling programme for trafficking survivors”, National

Skills Network, March 9, 2018, https://www.nationalskillsnetwork.in/pre-skilling-programme-for-trafficking-

survivors/

26 Dhaka Ahsania Mission, https://www.ahsaniamission.org.bd/field-works/tvet/ accessed on 27 March 2023

27 Raksha Nepal, https://www.younglivingfoundation.org/raksha-nepal accessed on 24 March 2023

28 Gentle Heart Foundation, https://www.ghfnepal.org/ accessed on 24 March 2022

29 Caballero-Anthony Mely, “A Hidden Scourge”, International Monetary Fund, September 2018,

https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/fandd/issues/2018/09/human-trafficking-in-southeast-asia-caballero

30 Mely, “A”

31 Sri Hartadi, et. al., “The empowerment strategy for prostitutes through competency-based culinary skills

training at Semarang Rehabilitation Center”, Jurnal Pendidikan dan Pemberdayaan Masyarakat (JPPM), 6 (1),

(2019),

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/334202971_The_empowerment_strategy_for_prostitutes_through_co

mpetency-based_culinary_skills_training_at_Semarang_Rehabilitation_Center

32 “2022 Trafficking in Persons Report: Malaysia”, US State Department, 2022,

https://www.state.gov/reports/2022-trafficking-in-persons-

report/malaysia/#:~:text=In%202021%2C%20the%20government%20identified,confirmed%20119%20victims

%20among%20487.

33 “2022 Trafficking in Persons Report: Malaysia”, US State Department, 2022,

https://www.state.gov/reports/2022-trafficking-in-persons-

report/malaysia/#:~:text=In%202021%2C%20the%20government%20identified,confirmed%20119%20victims

%20among%20487.

34 Cordisco Tsai, L. et. al., “They Did Not Pay Attention or Want to Listen When We Spoke”: Women’s

Experiences in a Trafficking-Specific Shelter in Cambodia, Affilia, 37(1),

(2022).151–168. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886109920984839

35 Ram Mohan Naidu Kinjarapu, “Skill training and entrepreneurship – inroads to alternate and well-paying

livelihoods for survivors of trafficking”, The Times of India, January 22, 2023,

https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/blogs/voices/skill-training-and-entrepreneurship-inroads-to-alternate-and-

well-paying-livelihoods-for-survivors-of-trafficking/

36 Kinjarapu, “Skill training”

37 Allie Gardner “Education as a Tool to Combat Human Trafficking”, United Way, January 17, 2023,

https://www.unitedway.org/blog/education-as-a-tool-to-combat-human-trafficking#

38 University of Calcutta, “Sonagachi in Perspective- A Social and Medico-Legal Study”, Department of Women

and Child Development and Social Welfare, Government of West Bengal, 2023 (Report submitted but

unpublished)

39 Interview with Binoy Krishna Mallick, Executive Director, Rights Jessore, on the Human Trafficking situation

in Bangladesh by Anasua Ray Chaudhury and Sreeparna Banerjee, WhatsApp call, 15 March 2021

40 Prateek Kukreja, “The G20 in a Post-COVID19 World: Bridging the Skills Gaps”, ORF, November 12, 2020,

https://www.orfonline.org/research/the-g20-in-a-post-covid19-world-bridging-the-skills-gaps/

41 “SKILL-UP Programme: Upgrading skills for the changing world of work”, International Labour

Organisation, https://www.ilo.org/skills/projects/skill-up/lang–en/index.htm accessed on 8 May 2023

42 “Trafficking in Persons Report July 2022”, 2022, https://www.state.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/337308-

2022-TIP-REPORT-inaccessible.pdf

43 “Reducing Vulnerability through Market Oriented Skills Training Interventions”, give.do,

https://give.do/projects/reducing-vulnerability-through-market-oriented-skills-training-interventions accessed on

2 May 2022

44 Kinjarapu, “Skill training”

45 “Human Trafficking in South Asia: Assessing the Effectiveness of Interventions Rapid Evidence

Assessment”, UK Aid, Heart, Foreign. Commonwealth and Development office, March 2020,

https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5f61d9c1e90e072bc30fa04b/REA_-

Trafficking_Mar_2020_FINAL.pdf

46 UK Aid, Heart, Foreign. Commonwealth and Development office, “Human Trafficking”

47 “UN Voluntary Trust Fund for Victims of Human Trafficking: 20 new NGO projects selected for emergency

grants under the sixth grant cycle”, UNODC, June 8, 2022,

https://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/frontpage/2022/June/un-voluntary-trust-fund-for-victims-of-human-

trafficking_-20-new-ngo-projects-selected-for-emergency-grants-under-the-sixth-grant-cycle.html