Task Force 5: Purpose and Performance: Reassessing the Global Financial Order

Philanthropy, centred on a multistakeholder approach and guided by data-led evidence, holds the power to impact macro-level actions. It can serve as a conduit for undertaking investment in local adaptation projects and help bridge the adaptation finance gap. Philanthropy can use a combination of economic advantages, such as low-cost loans and innovative financial instruments, as a powerful means to offset the risks foreseen by the private sector. Philanthropy can take up climate adaptation through advancement in research, infrastructure development and management, and ground-up sourcing of local, regional, and traditional knowledge. It aims to create accessibility to ensure sustainability through actionable and scalable ideas. This Policy Brief seeks to facilitate cross-learning of both, best practices and challenges across the G20 member countries while citing some examples from India, the presiding country.

1. The Challenge

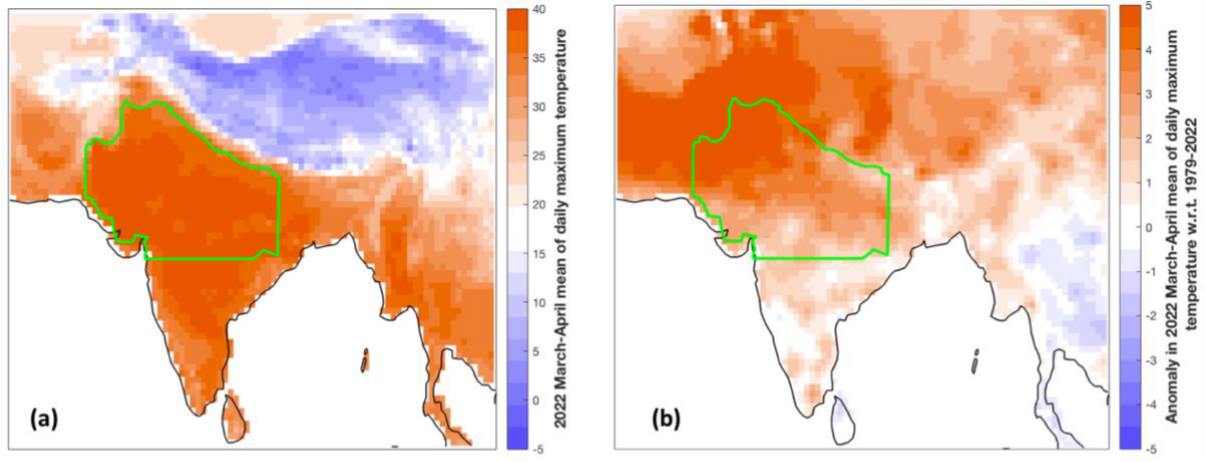

Climate change poses a veritable threat to humanity, and collaborative efforts from all stakeholders and communities are required to address the challenge. The global increase in temperature will lead to more intense heatwaves, heavier rainfall, and other weather extremes, which will further endanger ecosystems. Fig. 1 depicts the changes in temperature from 1979 to 2022. An Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report[1] has noted that rainfall intensity is increasing in South and Southeast Asia under enhanced greenhouse conditions, compared with the total rainfall intensity in particular regions.

Fig. 1. Temperature Changes (1979-2022)

Source: Tachev, 2022[2]

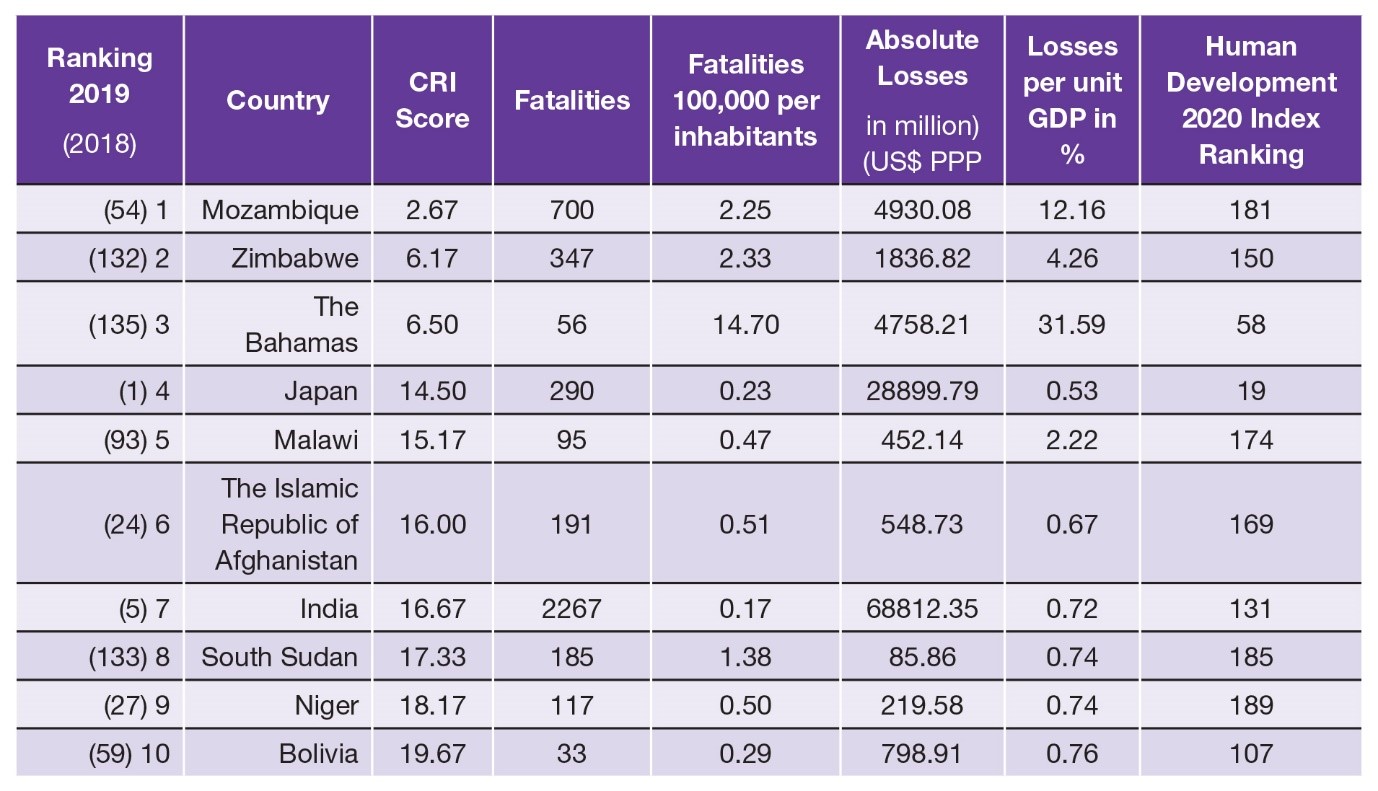

PPP=Purchasing Power Parity, GDP=Gross Domestic Product

Source: Eckstein, 2021[3]

As shown in Table 1, the countries which are most affected by climate change, as per the Climate Risk Index, belong to the Global South.

The role of philanthropy becomes critical as those who have contributed the least to climate change are being disproportionately affected by the consequences. Tribal populations, marginal farmers, migrants, and urban poor are the ones who bear the heaviest brunt of climate change. Adaptation comes with the challenges of uncertainty regarding which approach will work. Considering the diversity of regions and their contexts, it is important to not just look at a broader adaptation-level approach for all areas, but to also develop hyper-local solutions. This requires experimenting and innovating with different approaches to maximise the probability of finding varied solutions for local-level challenges.

Adaptation projects, typically, receive less funding than those on mitigation.[4] This is because mitigation includes creating a ‘product’ in the realms of energy, transport, and efficiency, and the agro-industrial sector. This directly benefits the private sector, which can sell it as a commodity.

Adaptation measures are generally concentrated at a local level and the positive externalities that they generate are a lot harder to sell as commodities.[5] Moreover, in the case of mitigation, the impact of solutions would be national and beyond, whereas in the case of adaptation, it is local and territorial. It is, therefore, harder to bring in resources from international funders. Considering the ever-increasing amount of adaptation costs, philanthropy can, therefore, take a more proactive role in promoting projects in this realm.

As per the principle of ‘differentiated but common responsibilities’, developed countries are required to support lower-income economies with adequate finance, technology, and capacity-building. However, as of 2019, the total contribution to the Copenhagen Green Climate Fund has amounted to only 10 percent of the total committed amount of $100 billion.[6]

2. The G20’s Role

The G20 represents inclusivity, particularly with the troika of global South countries (Indonesia, India, and Brazil) holding the previous, current, and forthcoming presidencies. This spotlights the agenda of developing countries and gives them the opportunity to present their unique challenges. India’s G20 theme, ‘Vasudhaiva Kutumbakam’ (‘One Earth, One Family, One Future’), aptly highlights the role of human beings as custodians of ecological resources. The following points are presented for the G20 member countries to consider.

Collaborative North-South Philanthropic Funding: The IPCC Sixth Assessment Report[7] notes that the current flow of global financing for adaptation is insufficient, hindering the implementation of adaptation programmes in developing countries. This is partly due to the lack of visibility of suitable options for investment in climate adaptation strategies in developing countries, including India. This is also because of interested foreign donors failing to rope in accredited state actors and implementing partners. Some global funding options come with certain thematic criteria of funding in climate-adjacent sectors—i.e., water, livelihood, and land restoration. In this regard, the G20 is best placed to provide a platform to connect global philanthropic funding options with requirements of local actors for climate action. A separate ‘Philanthropy 20’ platform can be created to facilitate stakeholder dialogues and conferences, which will aim to understand the mutual needs of the funding opportunities and the local requirements.

Joint Research Projects: Avenues to undertake joint research, with a focus on cross-learning and developing a database of best practices among civil society organisations for climate action, should be considered. Currently, the global South faces challenges to scientific analysis of climate change impact due to the non-availability of micro-level data and the lack of a finance and technology network to support the same. The knowledge gaps lead to inadequacies in planning for appropriate action. It also leads to weaknesses in driving forth the global South agenda on climate action vis-à-vis the narrative that is dominated by the wealthy countries. Even research in the global South is dominated by global North countries. The ratio of research on climate change in the global North to that in the global South is at 3:1.[8]

This research gap can be filled by philanthropy through the provision of research funding, which is more collaborative in nature. Joint research projects can include professionals working on climate action to undertake studies, based on primary data from local project implementing partners. Research collaborations should not be limited to the academia; they should also include practitioners and civil society partners to ensure adequate capture of local and Indigenous voices. Take, for example, the joint thought leadership project being undertaken by the EdelGive Foundation and the Evans School of Public Policy of the University of Washington to build an understanding of the women empowerment and climate action themes in India.

Mainstreaming Climate Action through Local Lexicon: In the discourse of climate action, there are multiple words in use. While experts in the domain refer to the context and the technical meanings of the words, as outlined in global reference reports, communities often use some of these words interchangeably. In the domain of philanthropy, developing a local terminology around climate action will be helpful. At the same time, the standard terminology needs to source data from the ground up, wherein the climate narrative is being framed through local languages. Developing such a terminology will help philanthropists across countries to be on same page while understanding projects for climate action. Building the lexicon also empowers communities as they can rightfully attribute the changes in their lives and environment to climate change.

Local media also plays an important role in attributing incidents of extreme weather and their subsequent impact on the local economy to climate change. In a diverse country like India, for example, which has multiple languages and cultures, it is important to have not only a national-level understanding, but also a community-level grasp of the impacts of climate change. This will drive local action, which is inclusive, participatory, and community-led. The G20 countries can share best practices around developing and disseminating a standardised taxonomy for climate change.

Mass Behavioural Change Campaign: In line with India’s narrative during COP27, focusing on ‘Sustainable Lifestyle’ as an approach to promoting mindful consumption, the G20 can step up efforts to bring in a mass behavioural change campaign. This puts the focus on individuals while examining climate action at the community level. Thought leaders working on climate action, from the field of philanthropy across the countries, can be roped in to build the narrative around bringing about the shift. India has, in this regard, developed a ‘LiFE Mission’, which aims to nurture sustainable individual lifestyles. Philanthropy can make it more actionable through the adoption of common pledges and leveraging the strength of social networks.

3. Recommendations to the G20

Promotion of Climate-Smart Agriculture: Climate-Smart Agriculture (CSA) enhances the capacities of agricultural systems to ensure food security and integrate the adaptation and mitigation strategies.[9] It is recognised as a means to manage natural resources, including land, water, forests, and fisheries while increasing the productivity and resilience of crops.[10] To facilitate and implement CSA, a set of policies, plans, technologies, and financial resources is required. Most importantly, it requires engagement with farmers, who are best placed to understand the local environment and food requirements.

CSA must be implemented in a decentralised way, with evaluation of locally produced and locally consumed food grains and types. Instead of promoting monocrops, CSA provides scope for bringing in diversity of crops. While governments need to bolster institutional infrastructure to promote and adopt CSA, philanthropy can provide the much needed support, specifically for small and marginal landholders to help them access credit as well as technical support.

Some of the recommendations are summarised in the following points:

- Philanthropist capital from the G20 countries must be combined to scale CSA in the global South for the most vulnerable.

- Research and development should focus on cultivars to promote the adoption of climate-smart crops like millets. South Asian countries are home to a rich gene pool of indigenous varieties, which are more resilient to changes in temperature and rainfall than the monocrops of wheat and paddy. The research support should be further extended to establish a viable market and supply chain system infrastructure, which is low-cost and sustainable. Policy-level interventions include proactive promotion of millets in local government schemes to encourage their consumption. At one of EdelGive Foundation’s programme sites in Odisha, an east Indian state, millets have flourished owing to the policy support from the government as well as philanthropy and CSR’s financial assistance to small and marginal farmers for procuring and selling millets.

- Community-based institutions, such as farmer producer organisations (FPOs), are important to collectivise the strengths of small farmers and provide them with an opportunity to create micro-businesses. However, such FPOs face the challenge of lack of long-term funding support to establish themselves as viable business ventures. Such community-based institutions need long-term nurturing and handholding, along with technical support for finance management, establishing market linkages, developing business plans, and becoming sustainable sources of income for small and marginal farmers. Initial investment in FPOs requires support from philanthropic grants as well as CSR funding to ensure establishment of the organisations, capacity-building as well as development of long-term business plans.

Enabling Access to Credit for Small Entrepreneurs through Blended Finance: Low-income regions and marginalised groups find it more difficult to attract funding. Blended finance can be used to experiment with innovative financial instruments, which enable access to credit for nano- and micro-entrepreneurs who are working on climate-smart livelihoods. Blended finance instruments can provide investors with distinct benefits, including the ability to tailor risks to specific needs. Financial institutions, such as non-banking financial companies (NBFCs) and microfinance institutions (MFIs), are often reluctant to lend to low-income individuals due to their lack of credit footprint; add to it their inability to provide collaterals to raise loans. In such situations, philanthropy has the power to provide the risk capital to innovate on financial instruments, both for experimenting with new constructs as well as for operationalising established ones.

- While providing adaptation solutions, capital is required for rebuilding lives and infrastructure, and re-establishing livelihoods and income-generating opportunities. While the private sector has been more forthcoming about extending support for livelihoods, compensating for loss and damages, and helping communities rebuild their housing and infrastructure have been primarily shouldered by philanthropy.

- Blended finance instruments can provide investors with distinct benefits, including the ability to tailor risks to specific needs, apart from capital loss protection and financial and social returns. These incentivise and mobilise philanthropic capital in emerging and frontier markets, where public resources are limited.

- Using philanthropic capital, which is inherently patient and multi-year, instruments, such as returnable grants (zero-interest loans with flexible repayment terms) and first loss default guarantees (FLDGs), can be operationalised for climate action-oriented micro-entrepreneurs. Some partner NGOs of EdelGive have worked on such programmes, which can be scaled to other G20 member countries.

- Catalytic financing is another tool at private foundations’ disposal. The leadership of philanthropic organisations has been incubating and expanding the field of ‘impact investing’, leading to inroads within the private sector. Philanthropies are appropriate partners for innovation as they can complement measures that the public sector can take to improve the risk-return balance while directly engaging with private sector partners.

Strengthen Climate-resilient Infrastructure in Communities: Community-based, climate-resilient infrastructure needs to be supported. Climate sensitivity-led landscape restoration can be undertaken, focusing on rehabilitating, restoring, and re-integrating natural ecosystems as part of the developmental process.[11] One such low-cost option can be exercised through integration with social security measures. Philanthropic capital can be combined with existing governance schemes. Social security measures can enhance the resilience of communities, specifically during contingencies. Revisiting India’s Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act 2005 (MGNREGA) can act as a tool to strengthen climate resilience. Environment-friendly public works remain an important criterion; however, going beyond these to ensure that the assets created help local communities enhance their income can facilitate their long-term maintenance as well. This can be carried out through participatory engagement and investing in assets that provide water availability to farmlands, and alternative avenues of income, such as fisheries. Philanthropic investment in climate-resilient infrastructure can lead to creation of models which can be adapted to and replicated in other regions by governments and the private sector.

Creation of a Digital Climate Risk-informed Toolkit: A climate risk-informed toolkit can help provision for all possible climate-induced scenarios and the preparedness required for them. It enables climate risk management through designing and implementing for uncertainty through informed decision-making. A district-wise study of India’s climate vulnerability has already been completed by the Council on Energy, Environment and Water (CEEW).[12] The study was commissioned by the India Climate Collaborative-EdelGive Foundation Alliance. The G20 members can support the global South countries for developing a digital database for the climate risk-informed toolkit, which is more real-time and dynamic. Funding for such studies from philanthropists can provide the much-needed independence to research. Furthermore, the technology and capacity-building support required from the global North can ensure that the database is able to capture granular datasets and accurately predict micro-level changes and the impacts of climate change.

Some of the proposed highlights of the database are summarised as below:

- The digital database should have a real-time information exchange on climate assessment. The real-time information is needed, considering the fast-changing impact of climate across the linear and temporal scales at micro levels. This database must fill the gap in science, policy, and community information exchange by decoding complex numbers and terms into simple actionable recommendations. Such a toolkit will also need to be socialised through innovative capacity-building mechanisms and funding support for its adequate translation at local levels to improve adaptive capacities.

- Philanthropy can enable funding for the toolkit for the benefit of the agricultural community so that they can have access to the latest information and technology in a readable format. It can be linked with the agricultural crop calendar with suitable recommendations of crops, based on climate change, that can be administered to farmers digitally through mobile phone updates.

- This digital assessment will also help facilitate climate vulnerability-based financial allocations for the most vulnerable regions. This allows donors to support their investment decisions, based on scientific assessments.

Social Innovation Hackathons: Social innovation hackathons are focused on creating social impact by bringing together all players in an ecosystem, including philanthropists, policymakers, social entrepreneurs, and members of civil society organisations. The experience of working with local NGO partners has shown that their models promise innovation, thoughtfulness, and keenness to maximise impact with minimal resources. Therefore, a social hackathon platform, facilitated by philanthropy, can provide civil society organisations with a chance to bring local innovations at the forefront and an opportunity to create a collaborative funding for the innovative idea/service/product. A social innovation hackathon, promoted by philanthropy, can also provide a way to innovate quickly and test hypotheses in a cost-effective manner. Such a collaborative hackathon to fund innovation can also be supported with mentors from across countries. The cross-country mentorship can further help in skill development and offer a chance to explore ideas, which can be scaled at the G20 level.

Incentives for Sustainability in Urban Areas: With rising heat conditions in urban regions, focus on sustainability in such areas is required. There is also a need for integrating climate risk profiling with infrastructure planning to increase the adaptive capacities of cities. The following are some specific recommendations in this regard:

- Integrating nature-based solutions into city planning, including restoring natural assets and promoting green and blue spaces, can be considered. A public-private partnership model, which aims to develop such assets in cities along with philanthropists to elevate the civil society’s engagement, can be explored. Philanthropic investment can adopt some of the low-income areas of cities and enable them to access energy-efficient solutions.

- Provide incentives, such as tax subsidies, to initiatives that are focused on the circular economy in urban areas. It may include subsidies to purchase reusable products and incentives to sell used products at recycling facilities. Philanthropy can participate in such discussions and support the formulation of such policies, which are conducive to climate action and community resilience at large.

Attribution: Sukhreet Bajwa and Deepa Gopalakrishnan, “Harnessing Philanthropy for Climate Action,” T20 Policy Brief, July 2023.

Endnotes

[1] Robert T Watson, Marufu C. Zinyowera, and Richard H. Moss, eds. Rep, The Regional Impacts of Climate Change: An Assessment of Vulnerability (Cambridge: IPCC, Cambridge University Press, 1998).

[2] Viktor Tachev, “2022 Heat Wave in India and Pakistan – New Scientific Report”, Energy Tracker Asia, July 15, 2022.

[3] David Eckstein, Vera Kunzel, and Laura Schafer, Global Climate Risk Index 2021 (Bonn: Germanwatch, 2021).

[4] Francesco Bassetti, “The Green Climate Fund Must Focus on Adaptation,” Foresight, November 14, 2019.

[5] Sharma, “Why India Needs a ‘Mission Adaptation”.

[6] The Hindu Businessline,“Climate finance: India hits out at developed countries for ‘reluctance’ to support projects” September 17, 2019.

[7] Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Synthesis Report for the IPCC Sixth Assessment Report (IPCC, 2023).

[8] Inayat Singh, and Alice Hopton, “Global South Suffering Gap in Climate Change Research as Rich Countries Drive Agenda,studies suggest.” CBC News, October 17, 2021.

[9] “Economics and Policy Innovations for Climate-Smart Agriculture”, FAO.

[10] “What is Climate-Smart Agriculture?”, World Bank, accessed 2023.

[11]Abinash Mohanty and Shreya Wadhawan, Mapping India’s Climate Vulnerability: A District-Level Assessment (New Delhi: Council on Energy, Environment and Water, 2021), India’s Climate Change Vulnerability Index | District-Wise Study (ceew.in)

[12]Abinash Mohanty and Shreya Wadhawan, Mapping India’s Climate Vulnerability: A District-Level Assessment (New Delhi: Council on Energy, Environment and Water, 2021), India’s Climate Change Vulnerability Index | District-Wise Study (ceew.in)