Task Force 1: Macroeconomics, Trade, and Livelihoods—Policy Coherence and International Coordination

The COVID-19 pandemic and the war in Ukraine have reignited the debate on efficiency versus resilience in international trade and global value chains (GVCs). This policy brief[a] (i) explains the contrasting perspectives of the private sector (primarily seeking efficiency) and the public sector (aiming for resilience); (ii) demonstrates that GVCs are still flourishing, despite some mounting signals of a geo-fragmentation leading to greater reallocation of the GVCs; and (iii) provides recommendations to help the G20 navigate the balancing act between efficiency and resilience considerations. Domestic policy design in the G20 countries and international coordination among these countries is essential.

1. The Challenge

The reliance on input producers across different geographical locations can lead to production disruptions when countries along the global value chain (GVC) experience negative shocks such as pandemics, conflicts resulting in economic sanctions, or natural disasters. Recent events such as the COVID-19 pandemic and the war in Ukraine have underscored the risks associated with trade integration and the use of GVCs. Consequently, many countries engaged in implementing nationalist industrial policies aimed at reducing their exposure to global hazards by encouraging companies to relocate their businesses back to their home countries.

For instance, the newly proposed Net-Zero Industry Act Commission intends to scale up the strategic autonomy of the European Union (EU) in clean-energy manufacturing. The anchor for this strategy is to produce 40 percent of the EU’s deployment needs by 2030. The strategy comes as the EU’s response to the US’s Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) launched in 2022, which aims to position the country as a pioneer in the green economy. The scope of these policies goes beyond the energy dimension. The European Commission has announced its goal to increase the EU’s market share of semiconductor production to 20 percent of global output by the end of the decade. The American Chips Act is another example of this trend, emphasising security, resilience, and robustness over efficiency in the organisation of GVCs.

One should not overlook the contrasting perspectives between the private and public sectors regarding the trade-off between efficiency and resilience. In broad terms, from the private sector perspective, which represents GVC owners and managers, reallocating activities closer to home may lead to losses in efficiency and profitability. In parallel, governments, from the perspective of industrial policymakers, prioritise and seek domestic resilience to shield their economies from global disruptions and, more recently, geopolitical and security threats. To entice the private sector, some governments resort to implementing—and bearing the fiscal cost of—necessary subsidies.[1]

The juxtaposition between the viewpoints of the private sector and the concerns of policymakers appears clear on the ground. This, amid an evolving context of still-dominant globalisation forces and growing protectionist measures, has produced a monumental policy challenge to balance wide-ranging economic, geopolitical, and other considerations. The following paragraphs clarify, and in some cases reframe, this challenge by adding more nuances that help reconcile seemingly conflictive policy priorities on resilience versus efficiency. In particular, it provides evidence in two areas: (i) the status quo of GVC relocation, and (ii) recent public sector actions on trade and GVCs as well as private sector perceptions and response.

Reallocation of GVCs is far from an established process

Expansion of trade in intermediate goods continues: Some economists are pointing out that there seems to be a clear disconnect between the discourse and the data. While headlines are dominated by news of relocation and its varieties, statistics show that trade continues to grow steadily. This is particularly evident when focusing on trade data that captures the dynamics of GVCs. The trend of trade in intermediate goods, which are used as an indicator of reliance on global suppliers for production inputs is increasing.[2] The value of trade in intermediates was about 25 percent higher in the second quarter of 2022 than it was in the same period in 2019. This rate of growth is almost double the growth rate of the global GDP (US$) over the same period.

China’s domestic market growth may reduce incentives to GVCs reallocation: China has sought to transition from an export-led growth model to a more balanced one that is driven by domestic consumption. This transition has been facilitated by a range of structural policies aimed at boosting consumer spending, such as increasing wages and social spending, and measures to liberalise financial markets and promote innovation. Despite short-term headwinds and slower long-term growth rates, the Chinese market remains attractive for both domestic and foreign firms.[3] Beyond supply-side factors, companies operating in or around the Chinese mainland may be less incentivised to relocate their supply chains, given the continued and growing importance of the Chinese domestic market as a source of demand.[b]

Global trade shifts towards services for resilience: In recent years, there has been a shift in the composition of global trade, with services trade growing at a faster rate than trade in goods. This trend is driven by several factors, including the increasing importance of knowledge-intensive services and the rise of digital technologies that have made it easier to trade services across borders. Importantly, research suggests that services GVCs are more resilient to shocks than goods GVCs, since services are less prone to supply chain disruptions and can often be delivered remotely.[4] This resilience was demonstrated during the COVID-19 pandemic, with services trade experiencing a smaller decline than goods trade.[5]

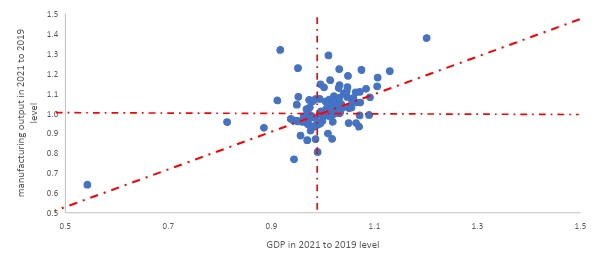

GVC trade did not compromise overall manufacturing rebound post COVID-19: Despite a severe 4.2-percent decline in 2020, global manufacturing output staged an impressive recovery in 2021, expanding by 9.4 percent.[6] As illustrated in Figure 1, in most economies, the rebound in manufacturing production outpaced the overall economic recovery. Over 60 percent of the countries in the sample experienced a resurgence in manufacturing output to, or above, pre-COVID-19 levels.

Figure 1: Rebound in Manufacturing Output Compared to Total Economic Activity Per Country (2021 vs 2019)

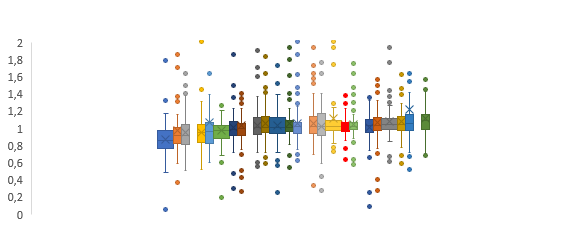

Moreover, industries characterised by their technological content, such as high-tech industries, have shown strong and above-average performance. In contrast, sectors such as leather and related products, as well as wearing apparel, have faced difficulties in returning to pre-COVID-19 levels (UNIDO, 2021) (Figure 2). The remarkable recovery and resilience observed in high-tech industries, which heavily rely on GVCs,[9] confirmed the significant role played by GVCs in facilitating the recovery and adjustment of the global economy.Figure 2: Manufacturing Performance Distribution (Ratio of 2021 output to 2019 output, across countries and industries)

Source: UNIDO,[10] authors calculations.

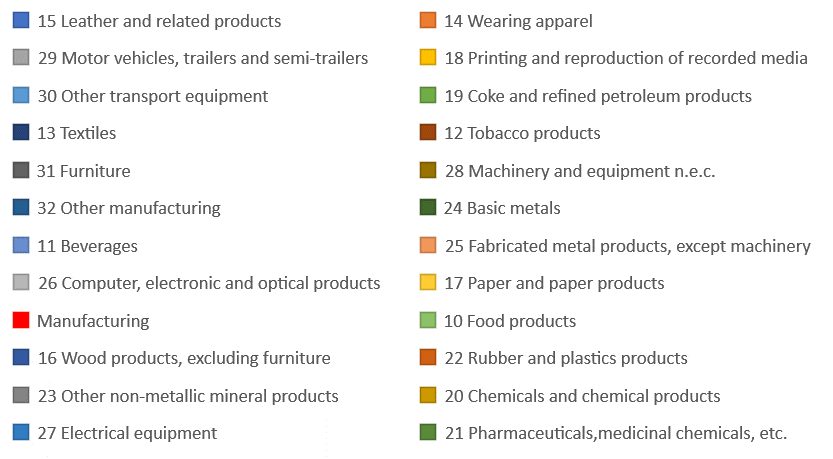

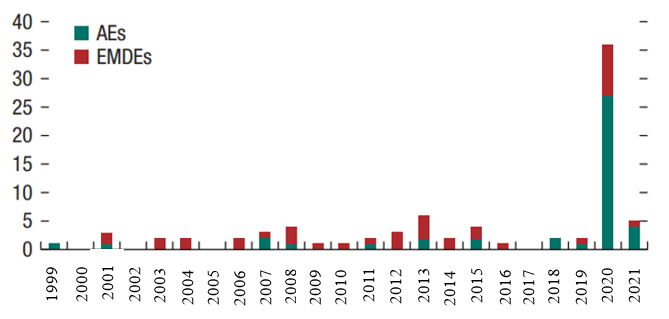

In recent years, global trade policy has seen a shift towards more protectionist measures. This trend can materialize through a variety of policy changes, such as the imposition of tariffs, the tightening of rules for foreign investment, and the renegotiation of trade agreements to include more restrictive terms. Some of the driving factors behind this shift are the desire to incentivise the reshoring or nearshoring of companies located abroad. Indeed, the Global Trade Alert reported in 2022 that the number of trade restriction measures implemented by countries are still on the upward trend, reaching a total of 2,500 measures. Another noteworthy aspect is that services are increasingly being subjected to restrictions over the years (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Number of Trade Restrictions Imposed

Source: Global Trade Alert, 2022[11]

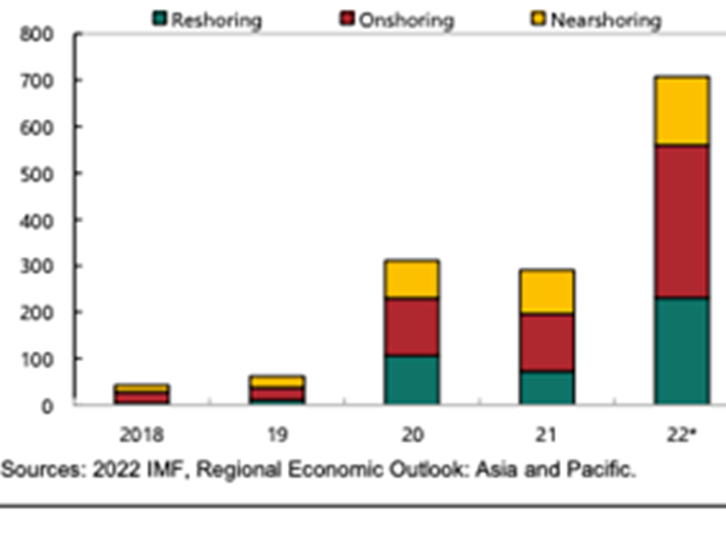

Figure 4: Number of FDIs inflows tightening measures

Source: IMF 2022, Regional Economic Report, Asia and Pacific.[12]

Figure 5: Number of Mentions of Key Terms in Corporate Presentations

Source: IMF 2022, Regional Economic Outlook, Asia and Pacific

Overall, on one hand, GVCs remain a vibrant dimension of the global economy and innovation. On the other, as countries increasingly prioritise reducing risk in their economic relations, the evolution and reallocation of GVCs become integral to this transformative shift. Effectively navigating this new paradigm requires striking a delicate balance between resilience and security, which is the public sector’s foremost concern, and efficiency, a significant objective of the private sector.

2. The G20’s Role

Many of today’s GVC challenges—and broader supply chain-related challenges such as food and energy insecurity—are inherently global in nature and scope. Tackling these global challenges requires equally global solutions, in particular, a careful (re-)calibration of “efficiency” versus “resilience” considerations. Certain trade and industrial policy practices recently implemented in G20 economies may contribute more to the challenges than to the solutions in the long run. Reining in such practices necessitates well-designed and level-headed domestic policy design, as well as greater international coordination. In this context, G20 has a unique opportunity and responsibility to lead in both areas.

- Domestic policy design: Domestically, G20 members can help mainstream definitions of “resilience” that include “efficiency”; better explain the benefits of GVC, globalisation, and international trade; and advance resilience without creating unnecessarily distortive subsidies or discouraging private sector investment. As the world’s largest economies, the domestic behaviour of G20 nations will have demonstration effects internationally.

- International coordination: G20 should play to its strengths. While the current structure and diverse interests of its members may limit the G20’s effectiveness in consensus building or binding agreements, it remains a powerful and high-level channel for private, informal consultations and policy dialogues indispensable to an eventual agreement. G20 sideline gatherings can be used as sounding boards to help inform trade and industrial policy ideas, amplify GVC best practices, harmonise members’ thinking on risk, resilience, and efficiency considerations as well as public versus private sector perspectives. It can also advance shared frameworks and guardrails to avoid an international race to the bottom of inefficient and distortive subsidies. Support from and coordination with international organisations can further catalyse these G20 efforts.

3. Recommendations to the G20

For individual G20 members in domestic policy design

1. Better define and balance efficiency-versus-resilience considerations when guiding new GVC creation:

- Present clear-eyed definitions of strategic sectors/products versus non-strategic ones: In simplified terms, resilience in the former through target support would be more justified, whereas unnecessary distortions in the latter should be limited. Enlisting an impartial “second opinion,” including the technical support of reputable international organisations Ios, could prove beneficial. As honest brokers with expertise and objectivity, international organisations can mitigate the disparities across G20 countries—such as, in terms of interest levels in engaging or leading related policy issues, technical capabilities to conduct such analysis, and idiosyncratic biases—and help identify potential areas of compatibility and coordination.

- Encourage greater domestic inter-agency coordination among trade, industry, finance, defines, environment, finance and other relevant ministries, whose priorities do not always coincide. To avoid contradictory domestic policies such as a simultaneous expansion of fossil fuel subsidies and green tax credits, a G20 government could adopt a more nuanced, broader and cross-ministerial definition of resilience, which includes and builds on efficiency rather than categorically rejecting it. The proper and efficient functioning of GVCs is, in fact, the best way to achieve resilience in many sectors and products. A surgical definition of resilience and strategic-versus-nonstrategic sectors is once again key.

- Actively engage the private sector and bridge contrasting perspectives between the private- and public-sectors about the efficiency–resilience trade-off. This divergence of public–private perspectives calls for more frequent and structured mechanisms of communication between governments and businesses. The B20 and its coordination with G20 will be particularly essential at both the national and international levels. Moving away from an over-simplified dichotomy between resilience and efficiency in GVCs—deemed by many firms as a false dichotomy or an over-correction—will be a constructive step.

2. Create competitiveness conditions to expand and maintain efficient GVCs:

- Where possible, these competitiveness conditions should be achieved through the strengthening of domestic economic fundamentals instead of distortive subsidies.[13] This includes policy actions to improve costs and scale of production, physical infrastructure, productivity and innovation; regulatory simplicity and certainty; export promotion and facilitation; and more. Past experiences in Latin America and North Africa demonstrated that in the long run, an outsize focus on import-substitution industrialisation—driven by subsidies and limited fundamental improvements—likely results in inefficient resource allocation, rather than sustained success or private-sector buy-in. In many sectors, G20 countries can and should utilise effective public institutions and policies, rather than distortive subsidies, to create better conditions for reshoring or nearshoring.

- Domestic policies in G20 countries should focus on broadening—and explaining to the general public—the benefits of GVC trade and globalisation. A public awareness campaign on such benefits—from poverty alleviation to more affordable prices for the consumers—is sorely needed in many G20 countries, where international trade has increasingly become the scapegoat for other economic woes, including structural job losses driven by technological advancements. Specific facts, such as the relative resilience of GVC trade and manufacturing during and after COVID-19, as described earlier, should be highlighted.

For collective G20 actions to enhance international coordination

1. Design policies, regulations, and coordination mechanisms to ensure smooth cross-border flows of GVC trade—especially of essential goods or components—among G20 economies in emergency situations such as a pandemic.

- While the G20 may not be the ideal platform for complex trade discussions, low-hanging fruits, which only entail a moderate amount of domestic investment and cross-border policy coordination, are achievable. The fact that similar recommendations have appeared in the final readout of the last three G20 Trade and Ministerial Ministers Meetings (Indonesia 2022,[14] Italy 2021,[15] and Saudi Arabia 2020[16]) demonstrates the broad buy-in from membership.

2. Provide guardrails against an international race-to-the-bottom in terms of inefficient or redundant supply chain and distortive trade practices created with widespread subsidies in the names of resilience, reshoring or national security.

- Find or create the right tools and/or international mechanisms to curb harmful subsidies. The WTO should be empowered and modernised instead of being undermined. While most G20 members support long-term actions to empower the multilateral trading system, deadlocked negotiations have persisted and hindered short-term results, including at the WTO. One major sticking point is subsidies, that is, how governments and IOs understand, treat, act on, cooperate around or enforce actions on subsidies. In this regard, the Subsidy Platform recently created by the IMF, OECD, World Bank and WTO, is a commendable effort that brings greater transparency to the discussion and that deserves greater G20 support.[17] More broadly, being the premier forum for international cooperation among the world’s largest and most advanced economies, the G20 has a special responsibility to lead by example in tackling subsidy issues. Distortive subsidies are particularly harmful for less developed countries that lack the fiscal space to compete in an all-out subsidy race for trade and industrial upgrading.

- Advance a common framework for risk quantification in GVCs, focusing on shared, global and non-political risks such as natural disasters. At least two barriers remain for moving the needle on a joint supply chain resilience agenda at the G20 level. First, most governments, G20 and beyond, and companies do not possess the know-how to accurately assess, factor and price supply-chain risks—and relatedly, supply-chain resilience. Second, competitive dynamics among G20 members make it difficult for them to agree on many risks related to geopolitics and geoeconomics. As a result, a constructive first step would be to focus on supply chain shocks and risks that are universal, non-political and non-partisan. For example, a handful of willing G20 members may pilot a risk quantification framework for the impact of climate events on specific supply chains in and across their countries. If and when successful, the framework can then be adapted and expanded to include other members and risks. Although quantification methods may vary greatly across different risks, this initial attempt at a shared framework for understanding and pricing risks is vital. Domestically, it would help strengthen the resilience of GVCs, improve risk prevention and mitigation efforts, and quantify the resources needed for such efforts. Internationally, it would eventually generate new data, transparency and comparability with respect to each country’s “resilience subsidies”. The IOs may assist both in national-level assessments and in cross-country comparisons.

- With subsidies already becoming more widespread, one constructive and realistic way forward may be to establish G20 guidelines around least-distortive and least-permanent industrial policy best practices.While industrial policies and subsidies may be necessary tools for domestic economic development, the increasing use of inefficient and distortive subsidies in certain industrial policies is a cause for concern, with international implications. The undesirable side effects will be felt most by less resourceful developing countries unable to compete on subsidies, especially if geoeconomic fragmentation continues to induce subsidy-based policies in richer nations. Avoiding an international race-to-the-bottom of “bad” subsidies while accommodating G20 and other countries’ legitimate demand for “good” subsidies necessitates a balancing act. As previously mentioned, the definitions of “resilience” and “strategic” need to be carefully calibrated. For example, building “resilience” in domestic N95 mask production and ensuring global dominance in semiconductors—in the name of resilience—may both be “strategic,” but require vastly different policies and subsidies. Additionally, one practical idea is for G20 governments to work with IOs to provide a set of technical guidelines and best practices in subsidy design and implementation. Such guidelines should include efficiency considerations, not only from a public spending perspective, but from an GVC/international trade perspective. This, coupled with other ideas explored in this policy brief, can contribute to the establishment or enhancement of valuable guardrails and rules that align with the current global context.

3. Build momentum towards next year’s Brazil G20/T20

- As with each year’s G20 host, Brazil G20 presidency in 2024 presents unique opportunities to advance international cooperation. With regard to trade and industrial policies, it would behoove the G20 to explore issues related to low-carbon and sustainable supply chains, consistent with the Lula’s administration interests in re-industrialisation and climate and sustainability issues. Agricultural collaboration and food security are other potential areas of interest, indicative of how efficient and well-integrated GVCs can maximise national and regional comparative advantages to help strengthen global resilience and tackle global challenges.

Attribution: Otaviano Canuto et al., “GVCs, Resilience and Efficiency Considerations: Improving Trade and Industrial Policy Design and Coordination,” T20 Policy Brief, June 2023.

[a]Ten current and former officials from G20 nations provided anonymous input that greatly enriched this report. The authors thank them for their time and insights.

[b] Asia boasts the world’s largest and fast-growing consumer base. For many multinational firms, China has been attractive not only for supply-side factors but also demand-side factors, such as consumers. Seen in this light, the reshoring movement is already a part of the current GVC design, and therefore is not completely new or one that would lead to a complete overhaul of existing GVCs.

[1] Otaviano Canuto, Abdelaaziz Ait Ali and Mahmoud Arbouch, “War, and Global Value Chains,” Policy Center for the New South, 2022.

[2] Uri Dadush, “Deglobalization and Protectionism,” Working Paper 18/2022, Bruegel, 2022.

[3] Tianlei Huang and Nicholas R. Lardy, “Foreign Corporates Investing in China Surged in 2021,” Peterson Institute of International Economics, 2021.

[4] United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, The Impact of COVID-19 on Global Value Chains and Trade: Updating the Evidence, UNCTAD, 2021.

[5] World Trade Organization, World Trade 2021 Rebounds but Challenges Remain, WTO, 2021.

[6] United Nations Industrial Development Organization, Annual Report 2021, UNIDO, 2021.

[7] “Home,” United Nations Industrial Development Organization.

[8] World Bank, World Development Indicators, World Bank, 2021.

[9] World Trade Organization, World Trade Report 2017: Trade, Technology, and Jobs, WTO, 2017.

[10] “Home,” United Nations Industrial Development Organization.

[11] Simon J. Evenett and Johannes Fritz, “Must Do Better: Trade & Industrial Policy and the SDGs,” Global Trade Alert, December 20, 2022.

[12] International Monetary Fund, “IMF 2022 Regional Economic Report: Asia and Pacific,” IMF, 2022.

[13] Otaviano Canuto, Justin Yifu Lin and Pepe Zhang, “Geopoliticized Industrial Policy Won’t Work,” Project Syndicate, February 24, 2022.

[14] G20 Indonesia, “G20 Chair’s Summary Trade, Investment and Industry Ministers Meeting,” G20, 2022.

[15] G20 Italy, “G20 Trade and Investment Ministerial Meeting,” G20, 2021.

[16] G20 Saudi Arabia, “G20 Trade and Investment Ministerial Meeting,” G20, 2020.