Task Force 6: Accelerating SDGs: Exploring New Pathways to the 2030 Agenda

The G20 aims to promote global cooperation, inclusive development, economic stability, and sustainable growth. This presents an opportunity to leverage its leadership to ensure foundational investments in gender-equitable family well-being globally. Family policies, such as childcare services and parental leave, can reduce poverty, promote decent jobs for women, support more equal intra-familial relationships, and secure child well-being and development outcomes, thereby benefitting societies and economies. To achieve this, family policies need to be designed in a gender-equitable way, and be integrated, coordinated, and financed through sustainable domestic resources. This policy brief proposes an agenda and recommendations to G20 countries to invest in gender-equitable family policies that can deliver optimally for child well-being, gender equality, and sustainable development.

1. The Challenge

Families are vital institutions that provide care for children, the elderly, and others in society[1] (see Appendix for a definition of key terms). Policies which aid families in meeting their material and non-material needs can be “the most meaningful vehicle for governments to influence the standard of living of future generations”[2]. Families, especially those living in environments of poverty, inequality, stress, and conflict, require significant support as highlighted by the negative impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic,[3] which saw an increase in care and domestic needs. This has further emphasised the importance of investing in families and in children during their foundational years as a means of ‘crisis proofing’.

Global evidence on family policies tells a story of chronic underinvestment, inequality, and flawed design.[4][5] This leaves families to resort to strategies such as increasing their private and out-of-pocket spending on health and education, reducing their participation in the labour market, engaging their children into labour or into early marriages, or migrating in search of better life opportunities and send home remittances.[6] In environments of stress, conflict, and relational inequality, family violence thrives—both violence against children[7] and women[8]—and often remains invisible and condoned by social norms. These lead to negative outcomes such as reduced breastfeeding, inadequate prenatal care, poor caregiver attachment, and significant societal and economic costs.[9][10]

Underinvestment in the early years

Public spending on children in the pre-school years is typically the lowest across age-groups,[11] regardless of a country’s income level. This is usually the stage of life when families require the most support from their governments. Underinvestment is particularly stark in low-income countries where children under the age of six receive only six percent of the total public spending on children under the age of 17.[12] The lack of early and adequate intervention perpetuates inequalities between families and contributes to the growing inequality within and between countries.

The hierarchy of spending within family policies can be influenced by a country’s demographic characteristics[13] and the extent of its informal economy[14]. However, spending and policy design decisions are ultimately policy choices that can be driven by short-term views, a lack of political commitment to gender equality and child well-being, and misperceptions about social spending as a cost rather than an investment.

Gender inequalities in care and domestic work

Across all G20 countries for which pre-COVID-19 data are available, women’s time spent on unpaid care and domestic work is consistently more than that spent by men. Data from India’s 2019 Time Use Survey show similar patterns,[15] and the picture for other low- and middle-income countries is even more bleak (see Appendix 2). Since the onset of COVID-19, while there has been an increase in men’s involvement in care and domestic work, women and girls still bear the majority of these responsibilities.[16] This not only has economic costs, estimated at nine percent of the global GDP, but also denies women and girls their rights and opportunities.[17]

Second, gender inequalities are often ingrained and perpetuated through policy design and implementation, leading to gender-discriminatory family policies. When policies are unequal or insufficient, or when they do not address underlying gender inequalities, they contribute to the continuation of these inequalities.[18] For instance, maternity leave that is either too short or too long coupled with the absence of paid paternity leave, may impact family decisions on who stays at home to care for children, based on existing care roles and earnings potential.[19][20] Women may end up leaving the workforce, or continue to work whilst relying on adolescent girls to undertake care work and chores within the home,[21] thereby compromising their schooling, or leaving young children at home alone, which endangers their safety and wellbeing.[22]

Costs of inaction or ‘bad action’

Family policies play a crucial role in addressing gender inequalities and children’s vulnerabilities. Failing to offer a comprehensive range of such policies undermines efforts to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) with widespread consequences.

Inadequate investments in maternal and newborn healthcare can lead to mortality, chronic illnesses, and long-term health challenges. Insufficient childcare services impede women’s earning potential resulting in lost wages. In the US, working families lose over US$8 billion due to insufficient childcare and US$20 billion due to lack of paid family and medical leave.[23] Limited opportunities, resources, and mobility also restrict women’s ability to protect themselves and their children from violence.[24] The absence or inadequacy of childcare or early childhood development and education services negatively affect children’s development.

2. The G20’s Role

Investing in gender-equitable and child-oriented family policies is crucial to ensure equality and well-being for families. Public funds contributing to, or worsening gender inequality is unacceptable as it violates human rights, wastes valuable skills and productivity, and hinders family functioning.

India’s G20 presidency has proposed the vision of ’One Earth, One Family and One Future’ to overcome these obstacles and achieve the SDGs by 2030. Intentionally designed family policies that promote gender equality and foundational child well-being can achieve this vision. This policy brief presents a call to action for G20 member and guest countries to invest in a comprehensive set of gender-equitable family policies that, when integrated and coordinated, can ensure sustainable development by securing child well-being and gender equality. Three areas for G20 countries to focus on are emphasised below.

First, governments need to expand the scope of family policies to cover a holistic view of care, including support for gender-equitable parenting, and promotion of foundational child well-being.

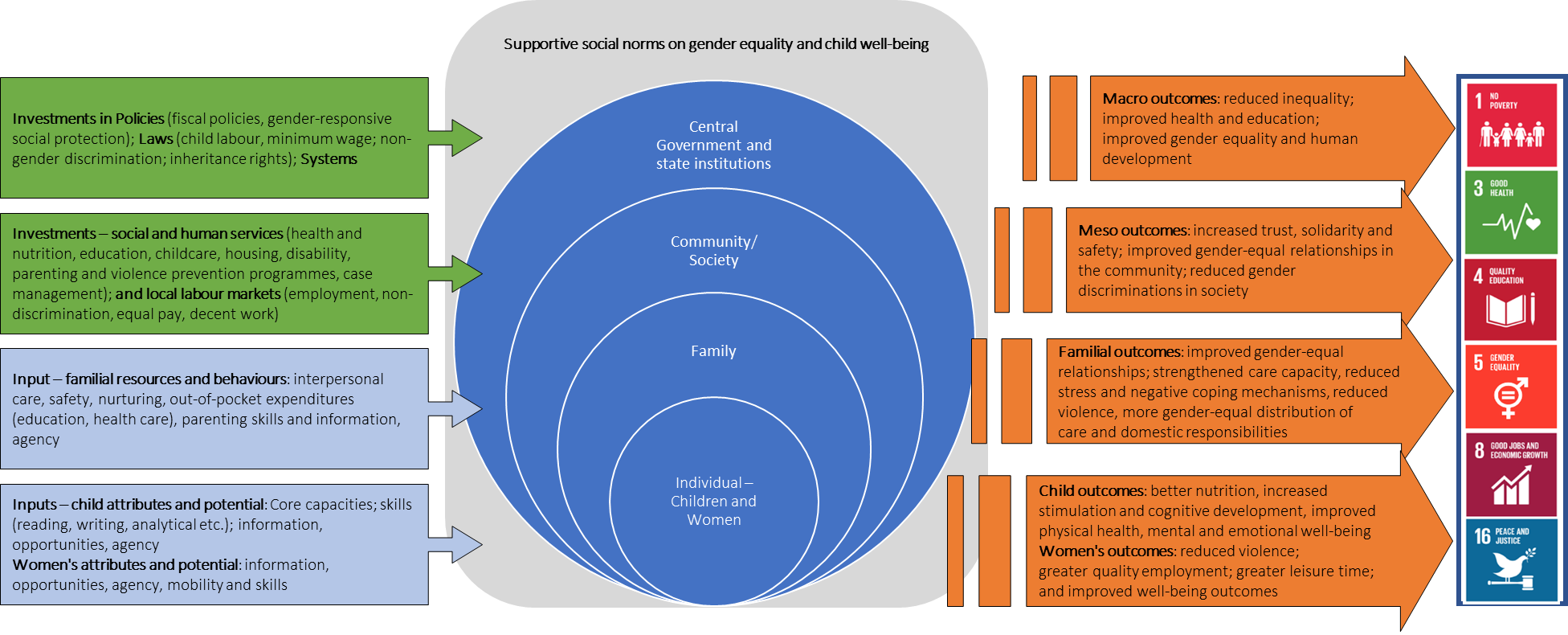

Doing so will strengthen families’ capacities to be resilient to global challenges. Thoughtfully designed and effectively implemented family policies have numerous positive effects on children, caregivers, intra-familial relationships, societies, and economies. Figure 3 illustrates the breadth of family policies and their outcomes based on available evidence adapted to Bronfenbrenner’s socioecological framework[25] that includes the individual child, family, community, and society, and macro levels. The G20 governments are uniquely positioned to establish national systems of family policies that set an example for other nations to follow.

Comprehensive family policies are essential for creating virtuous cycles of intergenerational prosperity and well-being. For example, provision of high-quality and accessible childcare services can increase women’s labour force participation[26] [27] and enhance children’s development.[28] [29] [30]At the family level, such policies can have positive effects. Paternity leave, for instance, can strengthen intra-familial relationships by promoting bonding between fathers and newborns and reducing maternal stress.[31]

Governments must, therefore, strategically plan their investments by concentrating on three key dimensions:

- creating social support for universal family policies to ensure that families, including the most impoverished and disadvantaged, receive resources, services and opportunities to level the playing field;

- promoting equitable interpersonal relationships between family members to reduce conflict and violence, and distribute opportunities and resources fairly within the family; and

- securing individual well-being outcomes for children and women, including improved nutrition, increased cognitive development and stimulation, better physical health, and enhanced emotional and mental well-being.

Figure 1: Conceptual framework for family policies

Source: Authors’ own.

Second, governments need to ensure family policies are integrated across sectors and designed and delivered in a gender-equitable way.

The failure to develop comprehensive family policies can be attributed to siloes in sectors and systems, leading to inefficiencies, duplication, and coverage gaps. The G20 has a responsibility to ensure that family policies are delivered in an integrated and coordinated manner to ensure effective reach and reduction of inequalities. National systems should consider the diversity of family types, structures, and compositions globally and provide benefits to all individual adults regardless of their employment, nationality, and residence status.[32] They should guarantee universal rights and opportunities for children and be inclusive of different life courses and family arrangements.[33]

Figure 1 details the laws, services, and cash benefits that must be included in a family policy system to provide gender-equitable care to families as described above. We spotlight three key areas that present an opportunity to transform family policies, promote gender equity, and benefit children, women, and families.

a) Expanding provision of both childcare and early childhood care and education (ECCE) services within a broader enabling environment

Providing both childcare and ECCE services is crucial for women’s economic participation and empowerment, as well as promoting nurturing care, development, and foundational learning for children.[34] Strategies to achieve this include offering affordable quality services located in convenient locations, with trained carers, and flexible operating hours that match the needs of parents and caregivers. Involving parents and families in these services to improve the quality of education is also essential.[35] Nesting such services within an enabling legal and regulatory environment would ensure their full utilisation. This includes extending maternity leave to cover the child’s first six months of life, during which exclusive breastfeeding is recommended by the United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF) and World Health Organization (WHO). Providing time and space for women to breastfeed in the workplace, and extending parental leave to cover the period up to when childcare services are provided are also crucial.[36]

b) Strengthening intra-familial relationships through parenting and social norms interventions.

Family policies should encompass interventions that prevent and respond to family violence as part of national systems. Parenting programmes, for instance, can help prevent violence via improvement of skills in managing relationships and behaviours, resolving conflict, and handling negative emotions that may be exacerbated by economic stress. Enhancing parental access to information resources is also crucial. Effective family violence-prevention programmes can be community-based or couples-focused and often promote equitable family dynamics as a central component. In Rwanda, the Bandebereho ‘Role Model’ programme engages men in maternal, newborn and child health, caregiving, and healthy couple relations. The Mapa: Happy Family for Filipino children programme in the Philippines focuses on strengthening parent-child relationships and supports positive parenting.[37] [38] These programmes engage both fathers and mothers in creating safe, supportive environments through participatory methods that foster trust and respect confidentiality. There are similarly positive examples from Australia, Turkey, and the US.[39] [40] [41]

c) Leveraging social protection benefits

Well-being and development outcomes for women and children have been positively impacted by social protection measures.[42] [43] These outcomes can be achieved by designing social protection programmes in a gender-equitable manner, such as ensuring universal provision, avoiding conditionalities that are assigned only to women in conditional cash transfers meant to improve child outcomes, and designing social protection programmes with targeted outcomes (e.g., child marriage or gender norms). Additionally, it is important to strengthen health, education, and protection systems to ensure quality services.

Governments should adequately finance their systems of family policies through public investments and call upon private-sector actors to crowd in additional investments. As the primary platform for international economic cooperation, encompassing 85 percent of the global GDP, the G20 Heads of State and Governments, along with Finance Ministers, possess a unique economic advantage to finance national systems of family policies with sustainable domestic resources generated through taxes, government contributions, as well as contributions from employers and individuals.

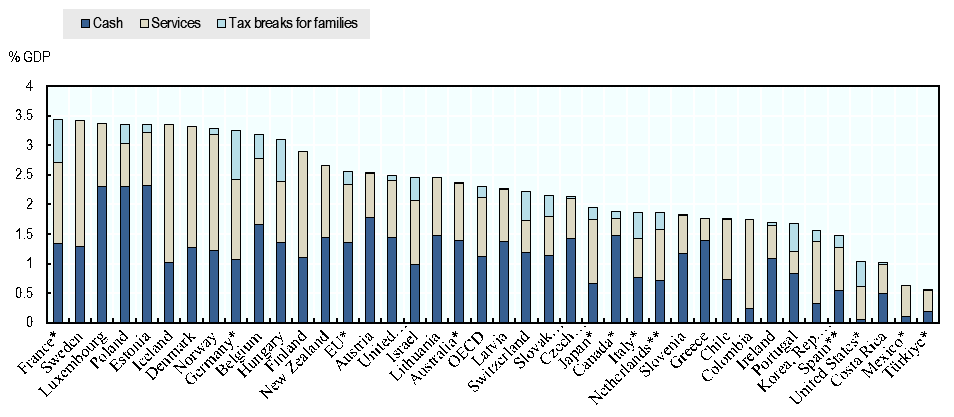

It is crucial to invest public funding in developing national systems of family policies that integrate and coordinate multiple sectors. The average public spending on family policies, including cash, services, and tax breaks, in OECD countries is 2.3 percent of their national GDP, with significant differences between countries and an over-reliance on cash in most cases (as shown in Figure 2). While laws, policies, and programmes are essential, direct public service provision is particularly necessary in situations where there is absence, inaccessibility, or poor quality of public and private services. This approach would benefit the most vulnerable families and create multiplier effects on local economies and societies, leading to better macro-level outcomes such as job creation and economic growth.

Figure 2: Public spending on family benefits

Note: Public spending on family benefits (child payments and allowances, parental leave benefits and childcare support, excluding other social policy areas such as health and housing support). * G20 member countries, ** G20 guest countries.

Source: OECD Family database, latest data available 2019.[44]

3. Recommendations to the G20

In light of the significant challenge ahead, we suggest a set of three recommendations for G20 member and guest countries.

Make a commitment to advancing gender-equitable, integrated family policies that promote child well-being and gender equality to achieve sustainable development.

The G20 governments are urged to:

- implement mandatory national policies for paid leave for parents and caregivers in both formal and informal economies; and

- support and facilitate exclusive breastfeeding for at least six months by providing time and space for mothers to breastfeed as long as they choose.

Increase investments in benefits and services that provide care and support during the critical early years of a child’s life and ensure that resources are distributed equitably to support care and parenting.

The G20 governments are urged to :

- progressively provide for universal access to affordable quality childcare;

- gradually implement universal child benefits; and

- invest in evidence-based family violence prevention programmes.

Recommendation #3: Ensure sufficient public and private funding and build broad-based political consensus on family policies as a top national priority.

The G20 heads of state/governments and finance ministers are urged to:

- allocate and redistribute resources towards establishing comprehensive national family policies that incorporate multiple sectors, coordinate diverse stakeholders, and benefit all families, while promoting gender equality and foundational child well-being; and

- promote widespread political backing for investments in national systems of family policies to ensure their sustainability over time, generate long-term benefits, and aid millions of families globally.

Appendices

Appendix 1: Concepts and definitions

Table 1: Concepts and definitions used in this policy brief

| Concept | Definition |

| Care | An overarching concept that involves both physical care such as bathing and feeding children, and emotional care such as playing with children. Caregiving includes caring for children or the elderly while domestic work includes cooking, cleaning, and shopping for the household. It can be unpaid, for instance in one’s own household or community, or paid, for instance in private homes or childcare centres. |

| Family | Families are a socially constructed institution (at times distinct from households though often overlapping), which are diverse in their structures and membership. While they are often thought of as a place of love and care, they can also be deeply unequal, where power inequalities can lead to violence and abuse, and where resources and responsibilities are unequally distributed.[45] [46] |

| Social reproduction | A range of social capacities that include “those available for birthing and raising children, caring for friends and family members, maintaining households and broader communities, and sustaining connections more generally”.[47] |

| Family policies | A range of policies that include “family-friendly policies” that encompass paid parental leave, support for breastfeeding, childcare, and child benefits and family allowances[48], and parenting and social norms interventions. |

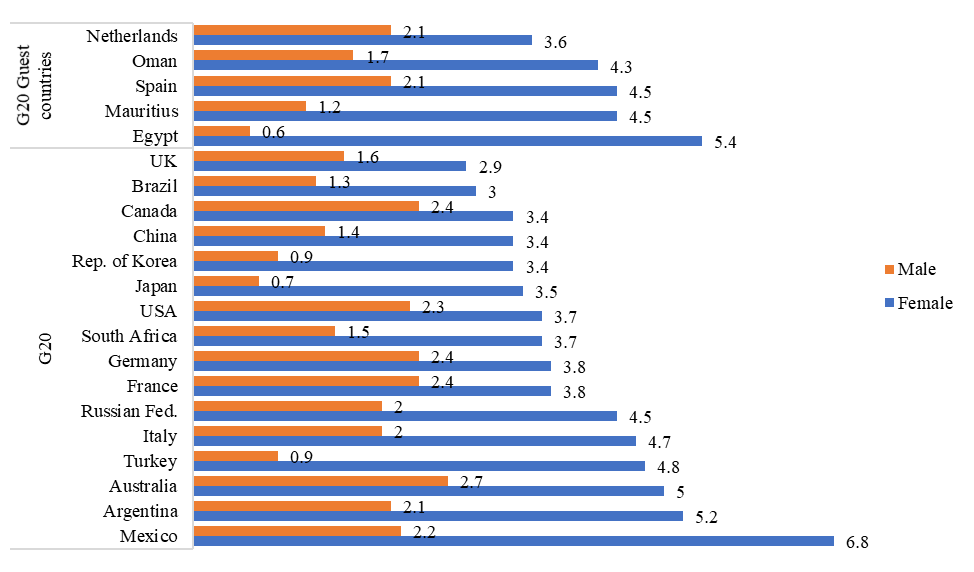

Gender inequalities in unpaid care and domestic work

Gender inequalities in the distribution of care and domestic work between women and men are widespread globally. Across the G20 countries for which pre-COVID-19 data are available, women consistently spend more time on unpaid care and domestic work than men, as illustrated in Figure 3. Canada has the smallest disparity while Mexico has the largest. Similarly, India’s 2019 Time Use Survey[49] indicates that women devote an hour more than men each day on unpaid caregiving, and over 3.5 hours more than men on unpaid domestic work. The situation is even worse in other low- and middle-income countries[50].

Figure 1: Average number of hours spent daily on unpaid care and domestic work by sex

Note: The bar chart shows the daily average number of hours spent on unpaid domestic chores and care work by women and men, for all countries for which time use survey data is available from the United Nations Statistics Division dashboard. For each group of countries, countries are ordered by average number of hours spent on unpaid care and domestic work undertaken by women.

Source: Authors’ elaboration

Appendix 2: Examples of family policies and their design features

Table 2: Family policies by type, corresponding sector, target age group, and gender-equitable and child-sensitive design features

| Type | Corresponding sector | Target age group | Gender-equitable and child-sensitive design features | |

| Laws | Maternity leave | Social protection and labour market | Mothers and children | Not less than 14 weeks at least at 67 percent replacement rate as per International Labour Organization (ILO) Convention No. 183.

Ideally up to the six months of age of the child, to fully cover the period of exclusive breastfeeding as per WHO and UNICEF recommended exclusive breastfeeding duration |

| Paternity leave | Fathers and children | Ideally equated to maternity leave in length and replacement rate | ||

| Parental leave | Parents and children | Non-transferrable, sufficiently long leave to cover until the start of childcare service provision and with sufficiently high wage replacement rate | ||

| Breastfeeding breaks | Working mothers and children under 2 | No established international standard or benchmark

|

||

| Flexible work hours and other workplace-related measures | Working parent or caregiver and children of any age | No established international standard or benchmark | ||

| Services | Childcare services | Education and care | Children 0-3 years | Trained workers with decent working conditions

Low staff-child ratio Flexible operating hours |

| Pre-school/ECCE | Children 4-5 years | |||

| Primary education | Children 6-11 years | Universal and free | ||

| Secondary and post-secondary education | Children 12+years | Universal and free | ||

| Case management and social work | Child protection | Any | No established international standard or benchmark | |

| Parenting and violence prevention programmes | Any | No established international standard or benchmark | ||

| Primary and secondary healthcare | Health | Any | Universal and free | |

| Pre-natal checks | Mothers and foetuses | At least four antenatal care (ANC) visits | ||

| Post-natal checks | Children | Continuous care in the first 24 hours after birth, and a minimum of three additional postnatal care contacts[51] | ||

| Immunisation | Children | As prescribed by relevant national and international standards | ||

| Home-visiting | Intersectoral | Parent or caregiver and children | No established international standard or benchmark | |

| Cash benefits or in-kind transfers | Family allowances | Social protection and labour market | Any | Unconditional and universal |

| Birth grant | Children at birth | Unconditional and progressively universal | ||

| Maternal and paternal benefits | Parent or caregiver and children up to 6 years | Ideally includes bonuses and incentives for fathers to take up paternity leave | ||

| Vouchers for childcare, tax relief for childcare | Parent or caregiver and children up to 6 years | Sufficiently large size of the childcare subsidy/ voucher

Flexibility with which the voucher/subsidy can be taken |

||

| Child-raising/home-care allowance | Parent or caregiver and children up to 6 years old | No established international standard or benchmark |

Source: Adapted from ILO and UNICEF (2023); Richardson (2015) and Richardson, Harris, and Hudson (2023).

Note: The table shows selected family policies (across laws, services, and cash benefits) with their corresponding sector (social protection and labour market, education and care, child protection, and health), from conception to adult age. The table excludes old age-related family policies (such as long-term care) in order to focus on those family policies that have the most immediate and impactful role on child well-being. For each family policy, it identifies the target age group of beneficiaries, and suggests gender-equitable and child-sensitive design features as per the latest and most rigorous evidence, and international standards.

Attribution: Elena Camilletti et al., “Gender-Equitable Family Policies for Inclusive and Sustainable Development: An Agenda for the G20,” T20 Policy Brief, July 2023.

Endnotes:

[1] United Nations Research Institute for Social Development, Why Care Matters for Social Development (Geneva: UNRISD, 2010).; Nancy Fraser, “Contradictions of Capital and Care,” New Left Review, July-Aug 2016.

[2] UNICEF Innocenti, Key Findings on Families, Family Policy and the Sustainable Development Goals: Synthesis Report (Florence: UNICEF Innocenti, 2019).

[3] E. Camilletti, and Z. Nesbitt-Ahmed, “COVID-19 and a “Crisis of Care”: A Feminist Analysis of Public Policy Responses to Paid and Unpaid Care and Domestic Work,” International Labour Review 161, no. 2 (2022), 10.1111/ilr.12354.

[4] Rosario Esteinou, “Family-Oriented Priorities, Policies and Programmes in the Implementation of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development as Reported in the Voluntary National Reviews of 2016, 2017, 2018 and 2019,” UNDESA Division for Inclusive Social Development, 2020.

[5] Dominic Richardson et al., “Too Little Too Late: Public Spending in Low- and Middle-Income Countries,” Innocenti Working Paper, 2023.

[6] Simone Cecchini, ed., “Protección Social Universal en América Latina y el Caribe. Textos Seleccionados 2006-2019,” CEPAL, 2019.

[7] Susan D. Hillis, James A. Mercy, and Janet R. Saul, “The Enduring Impact of Violence Against Children,” Psychology, Health & Medicine 137, no. 4 (2017): 393-405, https://doi.org/10.1080/13548506.2016.1153679.

[8] WHO, Violence Against Women Prevalence Estimates, 2018: Global, Regional and National Prevalence Estimates for Intimate Partner Violence Against Women and Global and Regional Prevalence Estimates for Non-Partner Sexual Violence Against Women: Executive Summary (Geneva: World Health Organization, 2021).

[9] UN Women, Economic Costs of Intimate Partner Violence Against Women in Ethiopia (New York: UN Women, 2022).

[10] IWPR, The Economic Cost of Intimate Partner Violence, Sexual Assault, and Stalking (Washington DC: IWPR, 2017).

[11] Richardson et al., “Too Little Too Late,” 8

[12] Richardson et al., “Too Little Too Late,” 7

[13] C. N. Focacci, “Old Versus Young: How Much Do Countries Spend on Social Benefits? Deterministic Modeling for Government Expenditure,” Quality & Quantity, 57 (2023): 363-377.

[14] S. Galiani, “Políticas Sociales: Instituciones, Información y Conocimiento,” Serie Políticas Sociales No. 116, 2006.

[15] National Statistical Office, Time Use in India-2019 (New Delhi: Government of India, Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation, 2019).

[16] UN Women, Women and Girls Left Behind: Glaring Gaps in Pandemic Responses (New York: UN Women, 2021).

[17] ILO, Care Work and Care Jobs for the Future of Decent Work (Geneva: ILO, 2018).

[18] I. Dobrotic, “Parenting Leave Policies and their Variations: Policy Developments in OECD Countries,” in The Oxford Handbook of Family Policy Over the Life Course, ed. Mary Daly et al. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2023), 679-694.

[19] UNICEF, Linking Family-Friendly Policies to Women’s Economic Empowerment: An Evidence Brief (New York: UNICEF, 2019).

[20] E. Del Rey, A. Kyriacou, and J. I. Silva, “Maternity Leave and Female Labor Force Participation: Evidence from 159 Countries,” Journal of Population Economics 34 (2021): 803-24.

[21] UN Women, Progress of the World’s Women: Transforming Economies, Realizing Rights (New York: UN Women, 2015).

[22] “Home Environment,” UNICEF Data, accessed May 29, 2023, https://data.unicef.org/topic/early-childhood-development/home-environment/.

[23] S. J. Glynn, and D. Corley, “The Cost of Work-Family Policy Inaction: Quantifying the Costs Families Currently Face as a Result of Lacking U.S. Work-Family Policies,” Centre for American Progress, September 2016.

[24] WHO, Violence Against Women Prevalence Estimates (WHO, 2021), https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/978924002668.

[25] Urie Bronfenbrenner, The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design (Harvard University Press, 1979).

[26] J-PAL Policy Insight, Access to Childcare to Improve Women’s Economic Empowerment (Cambridge: Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab, 2023).

[27] Andrés Hojman and Florencia López Bóo, “Cost-Effective Public Daycare in a Low-Income Economy Benefits Children and Mothers,” IZA Discussion Paper No. 12585 (2019).

[28] Ajayi Kehinde, Aziz Dao, and Estelle Koussoubé, “The Effects of Childcare on Women and Children: Evidence from a Randomized Evaluation in Burkina Faso,” CGD Working Paper No. 628 (2022).

[29] Raquel Bernal et al., “The Effects of the Transition from Home-Based Childcare to Childcare Centers on Children’s Health and Development in Colombia,” Early Childhood Research Quarterly 47 (2019): 418-31.

[30] Orazio Attanasio et al. (2022), “Public Childcare, Labor Market Outcomes of Caregivers, and Child Development: Experimental Evidence from Brazil,” Working Paper CWP19/22.

[31] UNICEF, Family-Friendly Policies, Redesigning the Workplace of the Future: A Policy Brief (New York: UNICEF, 2019).

[32] UNICEF, Linking Family-Friendly Policies

[33] Thomas Bahle, “Family Policies in Long-Term Perspective,” in The Oxford Handbook of Family Policy Over the Life Course, ed. Mary Daly et al. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2023).

[34] Ajayi et al., “The Effects of Childcare on Women and Children”

[35] Esteinou, “Family-Oriented Priorities, Policies and Programmes”; Ajayi et al., “The Effects of Childcare on Women and Children”; L. Alfers, “Our Children Do Not Get the Attention They Deserve: A Synthesis of Research Findings on Women Informal Workers and Child Care from Six Membership-Based Organizations,” Research Report, July 2016.

[36] UNICEF, Linking Family-Friendly Policies

[37] Doyle K et al., “Gender-Transformative Bandebereho Couples’ Intervention to Promote Male Engagement in Reproductive and Maternal Health and Violence Prevention in Rwanda: Findings from a Randomized Controlled Trial,” PLoS ONE 13, no. 4 (2018): e0192756.

[38] Lachman J. M. et al., “Effectiveness of a Parenting Programme to Reduce Violence in a Cash Transfer System in the Philippines: RCT with Follow-Up,” Lancet Reg Health Western Pacific 17, no. 100279 (2021), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lanwpc.2021.100279.

[39] M. E. Feinberg et al., “Couple-Focused Prevention at the Transition to Parenthood, a Randomized Trial: Effects on Coparenting, Parenting, Family Violence, and Parent and Child Adjustment,” Prevention Science: The Official Journal of the Society for Prevention Research 17 (2016): 751-764, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-016-0674-z.

[40] ADHOC and AÇEV, Final External Evaluation: “Fathers are Here for Gender Equality (ADHOC Research and Consultancy and Mother Child Education Foundation, 2019).

[41] Diemer K et al., Caring Dads Program: Helping Fathers Value Their Children – Three Site Independent Evaluation 2017-2020 (Melbourne: University of Melbourne, 2020).

[42] UNICEF and ILO, More Than a Billion Reasons: The Urgent Need to Build Universal Social Protection for Children (Geneva and New York: UNICEF and ILO, 2023).

[43] Camila Perera et al., “Impact of Social Protection on Gender Equality in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review of Reviews,” Campbell Systematic Reviews 18, no. 2 (2022).

[44] “OECD Family Database,” OECD, accessed May 29, 2023.

[45] Saraceno, Advanced Introduction to Family Policy

[46] UN Women, Progress of the World’s Women: Families in a Changing World (New York: UN Women, 2019).

[47] Fraser, “Contradictions of Capital and Care,” 99

[48] UNICEF, Family-Friendly Policies, 3

[49] NSO, Time Use in India

[50] UNSD, “Minimum Set of Gender Indicators,” accessed May 29, 2023.

[51] WHO, WHO Recommendations on Maternal and Newborn Care for a Positive Postnatal Experience (Geneva: WHO, 2022).