Task Force 6: Accelerating SDGs: Exploring New Pathways to the 2030 Agenda

Promoting holistic outcomes in health is a crucial imperative for healthcare systems globally, including those in the G20 nations. This approach encompasses not only addressing physical health concerns but also acknowledging the social, emotional, and economic factors that profoundly influence an individual’s overall well-being. Low-income and marginalised communities are particularly vulnerable to poor health outcomes. These groups often have limited access to healthcare services and face a range of social determinants of health that can negatively impact their physical and mental well-being. This policy brief discusses key issues concerning fragmented health systems within the G20. It offers actionable recommendations to confront these challenges and improve holistic health outcomes, with particular emphasis on uplifting vulnerable communities. The brief argues that the promotion of holistic outcomes in health for vulnerable communities is a complex and ongoing task that requires collaboration between healthcare providers, community organisations, and policymakers.

1. The Challenge

Fragmented health systems pose a significant challenge for numerous countries, including those in the G20.[1] The lack of integrated health systems can result in fragmented care, leading to a plethora of issues for patients and healthcare systems alike. The COVID-19 pandemic has brought to the forefront the utmost importance of adopting a holistic approach to health, considering its substantial impact on both physical and mental well-being.[2] It is imperative to address vulnerabilities in healthcare by identifying and mitigating factors that create obstacles to accessing quality care. This becomes particularly crucial for vulnerable communities, encompassing marginalised groups, low-income individuals, the elderly, people with disabilities, and those residing in remote or underserved areas.

The lack of integrated health systems in G20 nations poses several primary problems:

Lack of coordination, duplication of services, and high costs

The lack of effective coordination among healthcare providers leads to multiple issues, including duplication of services, exorbitant costs, and reduced efficiency. Such a fragmented system often results in unnecessary tests or procedures, causing financial strain on patients and the healthcare system alike. This especially affects marginalised populations. Additionally, the lack of tailored care for individual health needs can result in suboptimal outcomes and reduced patient satisfaction. Delays in treatment, miscommunication among providers, and increased healthcare costs ultimately impact the quality of care and patient outcomes.

Disconnected and/or inconsistent care

Patients receive inconsistent treatments based on location or healthcare provider, leading to suboptimal outcomes and reduced quality of life.

Inequities in access to care

Underserved populations often face significant barriers to healthcare, resulting in poor access and suboptimal health outcomes. Discrimination, limited resources, and poor healthcare infrastructure further exacerbate the lack of access to care. Fragmented care may also fail to address the complex health needs of marginalised populations, including mental, social, and environmental factors, further perpetuating health inequities.

Limited capacity and need for resilient health systems

The lack of integrated healthcare systems hinders effective response to public health emergencies, which require better coordination and infrastructure.[3] Marginalised populations may face additional systemic barriers such as inadequate healthcare infrastructures, limited funding,[4] and a shortage of healthcare providers, further exacerbating capacity challenges. For instance, during the peak of the Covid-19 pandemic, the terrible breakdown of the global medical supply chain led to severe shortages of vital frontline medical equipment and resources such as mechanical ventilators, personal protective equipment, hand sanitizers, and intensive care unit beds across several G20 nations.[5] This highlighted a critical gap in the coordination, integration, and management of global supply chains. Strengthening the supply chain, expanding telemedicine services, utilising emerging technologies like artificial intelligence (AI) and blockchain, and fostering collaboration between various stakeholders, including community and government, are crucial steps to create robust health systems. This will help ensure that essential medical equipment and resources are readily available, even during crises such as natural disasters and pandemics, to cater to the needs of all patients, including marginalised populations.[6]

Poor communication and information sharing

Communication breakdowns can lead to conditions of fragmented care where healthcare providers may not have access to complete and accurate medical information, resulting in medical errors and suboptimal treatment outcomes.[7] Poor communication and information sharing can also lead to delays in treatment, miscommunication among providers, and reduced patient satisfaction.

Data fragmentation

Patient data scattered across systems impedes gathering and sharing of information.[8] This can create challenges in the formulation of evidence-based policies and programmes to improve health outcomes, as well as gaps in patient information, reduced clinical decision-making, and increased costs due to duplicated tests and procedures. Data fragmentation can also hinder population health management and public health initiatives, making it difficult to identify and address health disparities and emerging health threats.

Lack of holistic care

Fragmented systems pay limited attention to the whole person, and care may be focused on individual symptoms or diseases.[9] This can lead to incomplete care, with patients receiving only partial treatment for their health needs, and neglect of preventive care, mental health, and social determinants of health (SDoH).[10] Addressing social determinants such as poverty, education, housing, and employment requires a systemic approach that can contribute to better health outcomes for vulnerable communities. This involves collaboration with non-healthcare sectors such as social workers, community organisations, and government agencies. Moreover, implementing integrated care models for patients with complex health needs will ensure comprehensive management of their conditions.

Previous studies involving five G20 countries reveal distinctive challenges within their healthcare systems. For instance, the US grapples with inadequate communication among healthcare providers, resulting in fragmented patient care. In Canada, the indigenous population and remote communities encounter significant inequities in accessing healthcare services. Meanwhile, Germany contends with soaring healthcare costs, necessitating the adoption of efficient cost-containment strategies. Brazil’s healthcare system lacks emphasis on preventive and holistic care approaches, and India struggles with high out-of-pocket expenses burdening individuals and families. However, it is crucial to acknowledge that the actual situation may vary from country to country, and specific regions or communities might face additional unique challenges.

2. The G20’s Role

Building integrated people-centric health systems to promote holistic outcomes in health is a pivotal objective for healthcare systems worldwide, particularly within the G20, whose member nations account for two-thirds of the global population. This vision aligns seamlessly with the World Health Organization’s global strategy of delivering “people-centred and integrated services.”[11] The mounting economic and social burden of chronic and preventable diseases in the G20 presents a significant challenge, necessitating complex interventions over extended periods.[12],[13] Furthermore, health emergencies, such as infectious disease outbreaks like COVID-19, and natural disasters, such as flood-induced cholera, exert excessive pressure on health systems.[14] Consequently, the need for integrated health services designed to promote holistic health outcomes becomes even more apparent.[15] Beyond merely addressing physical health issues, these health systems also account for social, emotional, and economic factors that influence an individual’s overall well-being. By doing so, these systems ensure effective preparedness and responsiveness to emergencies and outbreaks while maintaining continuity of care for escalating chronic care needs within the population.[16] Achieving such a paradigm shift requires significant changes in healthcare financing, administration, and provision. A key population segment of the G20 that is particularly vulnerable to poor health outcomes belongs to the lower socioeconomic or marginalised backgrounds.[17] Barriers such as geographical distance, scarcity of healthcare workers and medical supplies, and inefficient supply chains hinder their access to health services.[18] The challenges are particularly pronounced in rural or remote areas, where systemic issues exacerbate disparities, especially during health emergencies and natural disasters.[19] Furthermore, the availability of healthcare infrastructure varies widely among nations and regions. Addressing these disparities is crucial in building inclusive and equitable people-centric health systems.

Promoting holistic outcomes can yield multiple benefits and create promising opportunities for the G20 member nations. For one, it can help to effectively address the high burden of non-communicable diseases (NCDs) such as stroke, diabetes, and hypertension, which are often linked to lifestyle factors such as diet and exercise.[20] Encouraging holistic health practices empowers individuals to adopt healthier lifestyles and prevent these diseases. Additionally, this approach enables individuals to confront the root causes of mental health issues, leading to overall well-being improvement.[21] Moreover, fostering a people-centric approach can facilitate the development and exchange of digital platforms and technologies, such as telemedicine, among G20 nations.[22] This, in turn, can enhance healthcare accessibility and efficiency. Moreover, the G20 nations can leverage the pursuit of holistic health as an opportunity to establish task-specific regional consortiums. These consortiums can focus on critical areas like regional stockpiling of critical medical supplies in the Asia Pacific, Europe, or the Americas, to mitigate shortages and respond effectively to potential infectious disease outbreaks in the future.[23]

3. Recommendations to the G20

To address the problems outlined above, governments, policymakers, and healthcare providers in the G20 must prioritise the development of integrated health systems. These systems should be designed to foster seamless, patient-centred care across the entire continuum – from prevention and diagnosis to treatment and follow-up care.[24] One essential approach involves implementing electronic health records, adopting team-based care models, and establishing care coordination programmes. By doing so, we can ensure that patients receive timely and comprehensive care, precisely when they need it.

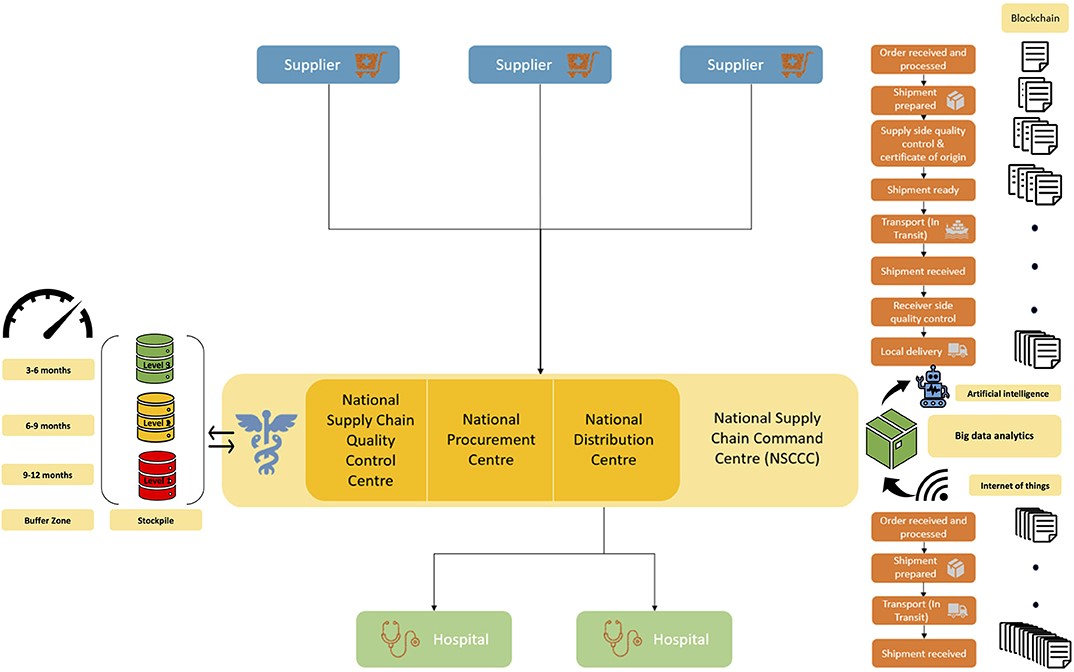

Figure 1: Proposed Model for Medical Global Supply Chain with Blockchain as a Connector and AI-based Demand Forecasting

Source: Bhaskar, Tan et al.[25]

The G20 countries must prioritise the development and implementation of national strategies for integrated care, fo

Develop and implement national strategies for integrated care and supply chain

stering better coordination and collaboration among healthcare providers and institutions.[26] To achieve this, it is crucial to explore various integrated care models and embrace team-based approaches, supported by electronic health records for seamless information sharing.[27] Additionally, enhancing the global medical supply chain requires the adoption of an integrated supply chain framework that leverages blockchain technology as a “connector” between supply chain stakeholders, such as buyers and suppliers. This framework aims to address gaps, eliminate inefficiencies, and establish robust automated systems (see Figure 1).[28] The proposed governance oversight and organisational structure make it highly suitable for scale-up, including at the G20 level. Moreover, to complement the supply chain model, the establishment of ‘regional stockpiling’ infrastructure and framework have been suggested.[29]

Promote value-based care

Governments and healthcare systems are urged to make a pivotal shift from traditional fee-for-service payment models to the more patient-centric approach of value-based care. This progressive model emphasises delivering exceptional healthcare services that not only ensure high-quality care and cost control[30] but also elevate the overall patient experience.[31] By adopting value-based care, healthcare providers are incentivised to concentrate on achieving favourable patient outcomes while addressing patients’ physical, mental, and social needs,[32] rather than merely focusing on the volume of services rendered.[33] In order to make this transition successful, a heightened emphasis on prevention, patient education, and robust social support systems in essential.

Invest in digital health technologies

Digital health technologies, including telehealth, wearables, and mobile health applications, play a crucial role in bridge gaps in healthcare and enhancing patient engagement.[34],[35] To foster the transition towards integrated and value-based care, G20 nations should invest significantly in these technologies. By leveraging technology, communication, and information sharing among healthcare providers in fragmented health systems can be greatly improved, with electronic health records and telehealth solutions enabling seamless and secure exchange of critical data.[36] Addressing the fragmentation of healthcare systems is of paramount importance in reducing costs and enhancing access to high-quality care, especially for marginalised populations in G20 countries. The standardisation of data formats and data-sharing policies is essential for enhancing data access, interoperability, and exchange among healthcare providers, leading to a reduction in redundant services,[37] and better clinical decision-making. Moreover, these initiatives can support effective population health management and promote public health initiatives.[38],[39] The COVID-19 pandemic demonstrated the significance of telemedicine as a fundamental aspect of our response, safeguarding healthcare workers and health systems from exposure while ensuring continuous care for patients.[40],[41] However, previous works published by the COVID-19 Pandemic Health System Resilience Program consortium, an independent not-for-profit think-tank dedicated to global pandemic preparedness and action with a focus on under-resourced settings, revealed substantial disparities in telemedicine provision, infrastructure, access, and literacy across the globe.[42],[43] Particularly in remote or rural areas and vulnerable communities, the penetration of telemedicine remains suboptimal, necessitating further efforts towards standardising telemedicine workflows using accessible tools for clinical examination.[44] Emerging technologies like AI and robotics offer immense potential for improving telemedicine and related systems of care and access.[45]

Develop and support care coordination programmes

G20 nations should establish effective care coordination programs aimed at fostering seamless communication and collaboration among healthcare providers, patients, and families. These well-coordinated initiatives hold the potential to significantly reduce redundancy in services, enhance the exchange of critical information, ensure consistency in care delivery, and ultimately support the provision of comprehensive and holistic healthcare.[46] The importance of consistent care cannot be overstated, particularly for patients with complex health needs who heavily rely on coordinated and continuous support to effectively manage their conditions.[47] Moreover, the prevalence of disconnected care can leave individuals feeling lost within the healthcare system, unsure of where to seek assistance. Such fragmentation not only leads to increased costs for both patients and health systems, as patients may require care from multiple providers or undergo repetitive tests and procedures, but also disproportionately impacts marginalised populations, exacerbating existing health disparities.[48]

Prioritise health equity

Integrated health systems must be purposefully designed to tackle health inequities, with a particular focus on G20 countries.[49] The prioritisation of efforts to reduce disparities in healthcare access, health outcomes, and overall health status among diverse population groups is crucial. To achieve this, integrated healthcare systems need to be established that emphasise equity in healthcare delivery, address systemic barriers, and foster coordination and collaboration among providers. These measures are critical in improving the health systems’ capabilities, mitigating health inequities, and ensuring marginalised populations’ access to high-quality care within the G20 countries.[50]

To address fragmented care and the lack of integrated health systems, a synchronised approach among policymakers, healthcare providers, and other stakeholders is imperative. By implementing these policy recommendations, substantial improvements in health outcomes, cost reduction, and the promotion of patient-centred, holistic care can be achieved within the G20 nations. Moreover, governments have a unique opportunity to advance equity, diminish disparities, and enhance health outcomes for vulnerable communities both within the G20 nations and beyond.

Implementation

The design of holistic people-centred integrated health care is essential for achieving universal health care, driven by principles of equity, health promotion, and disease prevention. This approach recognises and addresses the social, environmental, and economic determinants of health, including the underlying SDoH,[51] which significantly influence physical, mental, and overall well-being. For instance, individuals residing in neighbourhoods with poor air quality not only lack access to healthy food options but also experience heightened stress due to financial insecurity and discrimination. Emerging evidence suggests that people-centred integrated care strategies focused on holistic outcomes can significantly contribute to advancing universal health care,[52] particularly in providing optimal care for patients with multiple morbidities, chronic conditions, and vulnerable groups such as those with disabilities and individuals from low socioeconomic backgrounds, as well as the elderly.[53] Another crucial aspect of integrated care is the expansion and improvement of primary healthcare services, enhancing their quality and delivery.[54]

This brief makes additional suggestions to the G20 on implementing the recommendations put forth above. See Table 2 for the diverse responses to the healthcare challenges that vulnerable communities in G20 countries face.

Table 2: Examples of successful integrated health system strategies and specific strategies for vulnerable populations

| Country | Integrated Health System Strategies | Strategies Targeting Vulnerable Populations |

| Brazil | Community health worker programmes providing primary healthcare services and health education to vulnerable populations. | Implementation of community health worker programmes in underserved areas with a high concentration of vulnerable populations. |

| Canada | Utilisation of telemedicine networks to address access challenges in remote communities. | Deployment of mobile healthcare units equipped with telemedicine technology to reach isolated and vulnerable communities. |

| Germany | Implementation of collaborative care networks, such as accountable care organisations, to improve care coordination and outcomes. | Development of specialised healthcare programmes for refugee populations, providing comprehensive care and social integration assistance. |

| Australia | Robust health information exchange system enabling seamless sharing of patient information among healthcare providers. | Culturally sensitive and community-led Indigenous Health Services, addressing the unique needs of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander populations. |

| Rwanda | Implementation of health insurance schemes to ensure affordable healthcare for the entire population. | Introduction of specific health insurance programmes targeting low-income individuals and vulnerable populations. |

| US | Establishment of collaborative care networks, such as patient-centred medical homes to improve care coordination and outcomes. | Implementation of homeless health initiatives offering comprehensive healthcare services to individuals experiencing homelessness. |

| Japan | Successful implementation of a national health insurance system ensuring universal coverage and emphasising preventive care. | Introduction of subsidised health insurance programmes for low-income individuals and marginalised communities. |

| Kenya | Integration of HIV/AIDS treatment and prevention services into primary healthcare settings, ensuring access to care for vulnerable populations affected by the epidemic. | Development of mobile clinics to reach remote and marginalised communities, providing healthcare services, including maternal and child health care. |

| South Africa | Implementation of National Health Insurance (NHI), a comprehensive healthcare financing system aimed at providing equitable access to healthcare services for all citizens, with a focus on vulnerable populations and underserved areas. | Introduction of community-based healthcare programmes in informal settlements and rural areas, improving access to healthcare services for marginalised communities. |

| UK | Integration of health and social care services to provide seamless care for vulnerable populations, particularly the elderly and individuals with complex care needs. | Development of specialised mental health programmes targeting at-risk youth and vulnerable individuals, providing early intervention and support services. |

| Mexico | Implementation of Seguro Popular, a national health insurance programme, to expand access to healthcare for vulnerable populations, including those in poverty and the informal sector. | Introduction of mobile health units to provide healthcare services in remote and underserved areas, ensuring access to care for marginalised communities. |

To promote holistic outcomes in health for vulnerable communities, healthcare systems must prioritise addressing the SDoH alongside delivering medical services. This can be achieved through a range of strategic approaches, including:

a. Community-based participatory research:

This approach involves working with members of the community to identify the specific health challenges they face, and co-developing solutions that are tailored to the community’s unique needs and available resources.[55]

b Integrated healthcare:

By consolidating a diverse range of healthcare services, including primary care, behavioral health, and social services, all under one roof, patients can receive coordinated care that addresses both their physical and social needs.[56]

c. Addressing social determinants:

Addressing social determinants, such as poverty and lack of education, becomes crucial as they can exacerbate existing health issues.[57]

d. Health education:

Health education programs that provide education on healthy living practices, including nutrition and physical activity, can play a significant role in empowering individuals to proactively manage their well-being and foster a sense of control over personal health.[58]

Cross-sectoral collaboration and shared responsibility between local communities and healthcare organisations should be fostered to improve the quality of care and overall outcomes in healthcare.[59] By working together to address the SDoH and providing integrated, patient-centred care, we can ensure that everyone has the opportunity to lead a healthy and fulfilling life.[60] To achieve this, several key strategies should be implemented:

- Active intra-disciplinary collaboration between general practitioners and specialists.

- Seamless care transitions from hospital to community-based settings. Integrated EHRs can facilitate seamless information exchange between different healthcare entities, reducing medical errors and improving treatment outcomes.

- Delivery of tailored interventions, leveraging digital tools, emerging technologies such as mobile apps, and AI-driven self-care programs to empower individuals and promote population-wide improvements in NCDs. Investing in data analytics and population health management tools will help identify health disparities and emerging health threats promptly. Implementing interoperable health information systems will streamline data sharing and improve decision-making.

- Addressing SDoH whilst promoting active participation in decision-making and improving health system governance.[61],[62] Collaboration between healthcare providers and non-healthcare sectors like social workers, community organisations, and government agencies is essential to address SDoH effectively.

- Redesigning the health service delivery to enhance preparedness (including robust surveillance measures), response, and active community participation during all phases.

- Strengthening the health systems’ governance and accountability focusing on financing and supply chain sustainability, while also investing in the training and expansion of the healthcare workforce and ensuring the availability of essential drugs, medical supplies, and other psychosocial services.

- Improving the resilience of health systems by fostering inter-institutional collaborations between various stakeholders, including health systems, healthcare workers, communities, and local governments. Such partnerships will be instrumental in piloting, implementing, optimising, and scaling efficient models of care. Strengthening the supply chain, expanding telemedicine services, utilising emerging technologies like AI and blockchain are also crucial to build robust health systems.

- To address inequities in care, it is essential to invest in healthcare infrastructure in marginalised communities, improve funding for healthcare services, and actively work to eliminate systemic discrimination. Healthcare providers should adopt culturally competent practices and foster a more inclusive environment to ensure all patients receive equitable care.

The holistic approach to health recognises that achieving optimal well-being and addressing the complex health needs of individuals and communities requires collaboration and coordination among various stakeholders. In this context, the active involvement of the government plays a crucial role in facilitating and fostering partnerships among different entities. For instance, the government can initiate joint projects that bring together medical professionals, healthcare infrastructure providers, paramedics, social workers, and civil societies. By creating such collaborating endeavours, a comprehensive and integrated approach to healthcare delivery can be established, ensuring more effective solutions for the multifaceted health challenges faced by individuals and communities. Furthermore, the government’s provision of policy frameworks, funding, regulation, and oversight creates an enabling environment for holistic healthcare approaches to flourish, thus having a lasting impact on the well-being of the population. This approach recognises the need to address the broader determinants of health and provide comprehensive, person-centred care. By promoting holistic health, healthcare systems can help individuals build resilience and improve their overall well-being in the face of challenging circumstances. Addressing all aspects of an individual’s health, healthcare providers can offer high-quality, patient-centred care that improves health outcomes and enhances the quality of life.

Attribution: Sonu Bhaskar, “G20 Policy for Health Systems: Promoting Holistic Outcomes and Addressing Vulnerabilities in Healthcare,” T20 Policy Brief, July 2023.

Endnotes

[1] Isobel Devlin, Katrina L. Williams, and Kirstine Shrubsole, “Fragmented Care and Missed Opportunities: The Experiences of Adults with Myasthenia Gravis in Accessing and Receiving Allied Health Care in Australia,” Disability and Rehabilitation (2022).

[2] Jeffrey D. Sachs et al., “The Lancet COVID-19 Commission,” The Lancet 396, no. 10249 (2020).

[3] WHO Regional Office of Europe, “Integrated Care Models: An Overview,” in Integrated Care Models: An Overview (2016).

[4] GBD 2020 Health Financing Collaborator Network, “Tracking Development Assistance for Health and for COVID-19: A Review of Development Assistance, Government, Out-of-Pocket, and Other Private Spending on Health for 204 Countries and Territories, 1990-2050,” The Lancet 398, no. 10308 (2021).

[5] Sonu Bhaskar et al., “Call for Action to Address Equity and Justice Divide During COVID-19,” Frontiers in Psychiatry 11 (2020).

[6] J. N. Doetsch et al., “Strengthening Resilience of Healthcare Systems by Focusing on Perinatal and Maternal Healthcare Access and Quality,” The Lancet Regional Health – Europe 21 (2022).

[7] Devlin, Williams, and Shrubsole, “Fragmented Care and Missed Opportunities”

[8] Han Qiu et al., “Secure Health Data Sharing for Medical Cyber-Physical Systems for the Healthcare 4.0,” IEEE Journal of Biomedical and Health Informatics 24, no. 9 (2020).

[9] I. Gede Juanamasta et al., “Holistic Care Management of Diabetes Mellitus: An Integrative Review,” International Journal of Preventive Medicine 12 (2021).

[10] NEJM Catalyst, “Social Determinants of Health (SDOH),” NEJM Catalyst 3, no. 6 (2017).

[11] WHO, WHO Global Strategy on People-Centred and Integrated Health Services: Interim Report (WHO, 2015).

[12] Jonathan M. Kocarnik et al., “Cancer Incidence, Mortality, Years of Life Lost, Years Lived with Disability, and Disability-Adjusted Life Years for 29 Cancer Groups from 2010 to 2019: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019,” JAMA Oncology 8, no. 3 (2022).

[13] Sonu Bhaskar et al., “Key Strategies for Clinical Management and Improvement of Healthcare Services for Cardiovascular Disease and Diabetes Patients in the Coronavirus (COVID-19) Settings: Recommendations from the REPROGRAM Consortium,” Frontiers in Cardiovascular Medicine 7 (2020).

[14] J. Izagirre-Olaizola, G. Hernando-Saratxaga, and M. S. Aguirre-García, “Integration of Health Care in the Basque Country During COVID-19: The Importance of an Integrated Care Management Approach in Times of Emergency,” Prim Health Care Res Dev 22 (2021).

[15] Lia Patrício et al., “Leveraging Service Design for Healthcare Transformation: Toward People-Centered, Integrated, and Technology-Enabled Healthcare Systems,” Journal of Service Management 31, no. 5 (2020).

[16] S. Bhaskar et al., “Telemedicine as the New Outpatient Clinic Gone Digital: Position Paper From the Pandemic Health System REsilience PROGRAM (REPROGRAM) International Consortium (Part 2),” Frontiers in Public Health 8 (2020).

[17] Bhaskar et al., “Call for Action”

[18] Bhaskar et al., “Key Strategies for Clinical Management”

[19] Bhaskar et al., “Telemedicine as the New Outpatient Clinic Gone Digital”

[20] Bhaskar et al., “Key Strategies for Clinical Management”

[21] Lola Kola, “Global Mental Health and COVID-19,” The Lancet Psychiatry 7, no. 8 (2020).

[22] S. Bhaskar et al., “Designing Futuristic Telemedicine Using Artificial Intelligence and Robotics in the COVID-19 Era,” Frontiers in Public Health 8 (2020).

[23] S. Bhaskar et al., “At the Epicenter of COVID-19: The Tragic Failure of the Global Supply Chain for Medical Supplies,” Front Public Health 8 (2020).

[24] Patrício et al., “Leveraging Service Design for Healthcare Transformation”

[25] Bhaskar et al., “At the Epicenter of COVID-19”

[26] Gerald Bloom et al., “Next Steps Towards Universal Health Coverage Call for Global Leadership,” BMJ 365 (2019).

[27] Lisa de Saxe Zerden et al., “Harnessing the Electronic Health Record to Advance Integrated Care,” Families, Systems, & Health 39, no. 1 (2021).

[28] Bhaskar et al., “At the Epicenter of COVID-19”

[29] Bhaskar et al., “At the Epicenter of COVID-19”

[30] World Economic Forum, The Moment of Truth for Healthcare Spending: How Payment Models can Transform Healthcare Systems: Insight Report (WEF, 2023).

[31] Thomas Lee and Michael Porter, The Strategy that Will Fix Healthcare (Boston: Harvard Business Review, 2013).

[32] Patrício et al., “Leveraging Service Design for Healthcare Transformation”

[33] Stefan Larsson, Jennifer Clawson, and Robert Howard, “Value-Based Health Care at an Inflection Point: A Global Agenda for the Next Decade,” NEJM Catalyst Innovations in Care Delivery 4, no. 1 (2023).

[34] S. Whitelaw et al., “Applications of Digital Technology in COVID-19 Pandemic Planning and Response,” The Lancet Digital Health 2, no. 8 (2020).

[35] F. Rossetto et al., “A Digital Health Home Intervention for People Within the Alzheimer’s Disease Continuum: Results from the Ability-TelerehABILITation Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial,” Ann Med 55, no. 1 (2023).

[36] S. M. M. Bhaskar, “The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on e-Services and Digital Tools Development in Medicine,” in Cardiovascular Complications of COVID-19: Acute and Long-Term Impacts, ed. Maciej Banach (Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2022).

[37] Y. Gilboa et al., “Effectiveness of a Tele-Rehabilitation Intervention to Improve Performance and Reduce Morbidity for People Post Hip Fracture – Study Protocol for a Randomized Controlled Trial,” BMC Geriatr 19, no. 1 (2019).

[38] A. Jay Holmgren, Vaishali Patel, and Julia Adler-Milstein, “Progress in Interoperability: Measuring US Hospitals’ Engagement in Sharing Patient Data,” Health Affairs 36, no. 10 (2017).

[39] Rateb Jabbar et al., Blockchain Technology for Healthcare: Enhancing Shared Electronic Health Record Interoperability and Integrity (2020).

[40] Bhaskar, “The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on e-Services and Digital Tools Development in Medicine”

[41] S. Bhaskar et al., “Telemedicine During and Beyond COVID-19,” Frontiers in Public Health 9 (2021).

[42] Bhaskar et al., “Telemedicine as the New Outpatient Clinic Gone Digital”

[43] Bhaskar et al., “Telemedicine as the New Outpatient Clinic Gone Digital”

[44] M. Moccia et al., “Assessing Disability and Relapses in Multiple Sclerosis on Tele-Neurology,” Neurol Sci 41, no. 6 (2020).

[45] Bhaskar et al., “Designing Futuristic Telemedicine”

[46] J. L. Clarke et al., “An Innovative Approach to Health Care Delivery for Patients with Chronic Conditions,” Popul Health Manag 20, no. 1 (2017).

[47] Thomas Bodenheimer, “Coordinating Care: A Perilous Journey Through the Health Care System,” New England Journal of Medicine 358, no. 10 (2008).

[48] Maria Alcocer Alkureishi et al., “Digitally Disconnected: Qualitative Study of Patient Perspectives on the Digital Divide and Potential Solutions,” JMIR Human Factors 8, no. 4 (2021).

[49] Danielle Brooks et al., “Developing a Framework for Integrating Health Equity into the Learning Health System,” Learning Health Systems 1, no. 3 (2017).

[50] Amy M. Kilbourne et al., “Advancing Health Disparities Research Within the Health Care System: A Conceptual Framework,” American Journal of Public Health 96, no. 12 (2006).

[51] K. Cresswell et al., “Socio-Organizational Dimensions: The Key to Advancing the Shared Care Record Agenda in Health and Social Care,” J Med Internet Res 25 (2023).

[52] NEJM Catalyst, “Social Determinants of Health”

[53] WHO Regional Office of Europe, Integrated Care Models

[54] WHO, WHO Global Strategy on People-Centred and Integrated Health Services

[55] Meera Viswanathan et al., “Community‐Based Participatory Research: Assessing the Evidence: Summary,” in AHRQ Evidence Report Summaries (2004).

[56] Patrício et al., “Leveraging Service Design for Healthcare Transformation”

[57] NEJM Catalyst, “Social Determinants of Health”

[58] Paul Thomas et al., “Community-Oriented Integrated Care and Health Promotion–Views from the Street,” London Journal of Primary Care 7, no. 5 (2015).

[59] Miranda Joy Pollock et al., “Preparedness and Community Resilience in Disaster-Prone Areas: Cross-Sectoral Collaborations in South Louisiana, 2018,” American Journal of Public Health 109, no. S4 (2019).

[60] WHO, WHO Global Strategy on People-Centred and Integrated Health Services

[61] NEJM Catalyst, “Social Determinants of Health”

[62] Cresswell et al., “Socio-Organizational Dimensions”