Task Force 7: Towards Reformed Multilateralism: Transforming Global Institutions and Frameworks

Abstract

The United Nations (UN) heavily relies on voluntary contributions, made at the discretion of individual member states, while assessed contributions – i.e. membership fees – make up a relatively small part of most UN budgets. In the context of major geopolitical shifts, voluntary funding becomes increasingly unpredictable and in danger of falling prey to divisions among UN membership. This Policy Brief argues that the G20 – comprising key representatives from six continents and the most important contributors to the UN regular budget – is uniquely positioned to strengthen the operative abilities and the strategic capacities of the UN system through a reinvigoration of member states’ assessed contributions. As having a well-functioning and responsive UN is, ultimately, in the self-interest of the G20 countries, a G20 proposal for UN funding reform should include: (1) raising assessed contribution levels to at least 50 percent of overall budgets to ensure that the key functions of the UN do not heavily rely on discretionary funds; (2) expanding the use of assessed contributions to the 13 UN entities that receive only voluntary forms of member state funding; (3) tweaking the formula used to calculate assessed contributions to give due consideration to additional indicators that reflect how member states relate to major global challenges; and (4) reinforcing institutional mechanisms for penalising late payments to keep up the payment morale in a highly volatile geopolitical context.

1. The Challenge[1]

The United Nations (UN) is the world’s foremost multilateral organisation, currently comprising 193 member states. In addition to the UN proper, the UN system comprises a wide variety of specialised agencies, funds, programmes and other related entities.[2] Member state funding for the UN system is the backbone of UN work[3] and is primarily channelled through two main sources. First, membership fees are obligatory payments made by states to fund the regular budget of the UN that is supposed to cover the organisation’s core activities, such as expenditure for headquarters personnel, conferences and UN missions.[4] These fees are also called “assessed” contributions as they are calculated based on a multilaterally determined Scale of Assessments,[5] Second, “voluntary” contributions are resources that member states provide on a discretionary basis, often as ‘earmarked’ resources for predefined purposes, such as particular lines of work or specific projects.[6]

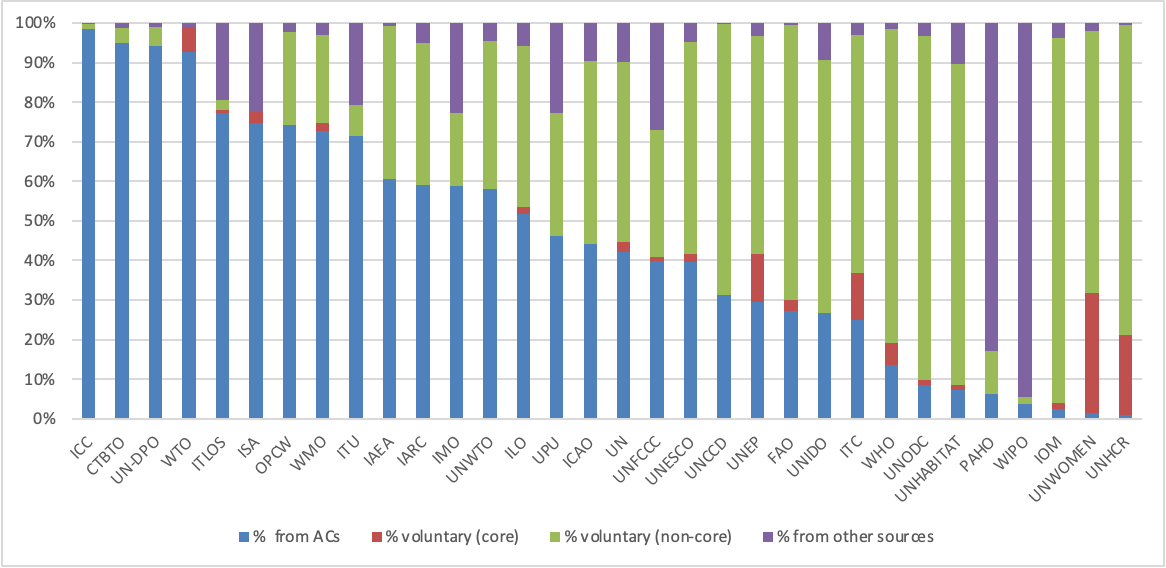

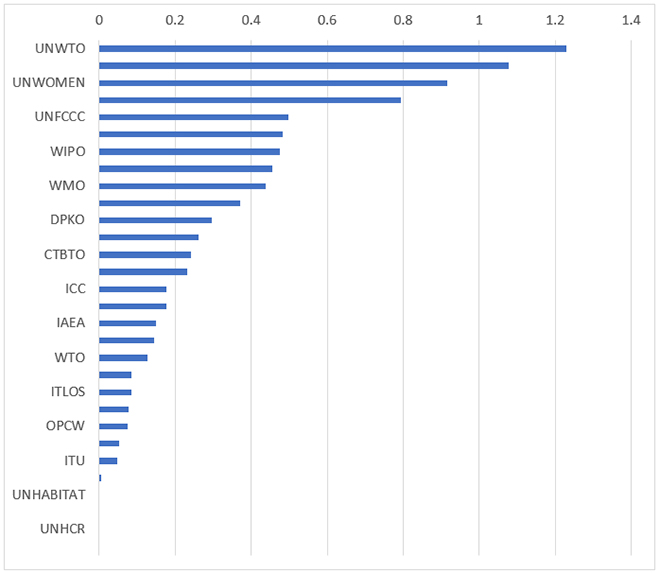

Fig. 1. Revenue by Grant Financing Type for UN Entities That Receive Assessed Contributions (2021)

Source: Authors’ own, based on CEB data, accessed on 14 May 2023

Overall, the UN system heavily relies on voluntary contributions made at the discretion of individual member states, while assessed contributions cover a relatively small part of most UN budgets. Currently, 30 out of 47 UN entities, whose data are included in system-wide reporting, including the UN proper and all specialised agencies receive assessed contributions.[7] The majority of these entities (17 out of 30), however, receive more than half of their revenue from sources other than assessed contributions (Fig. 1).

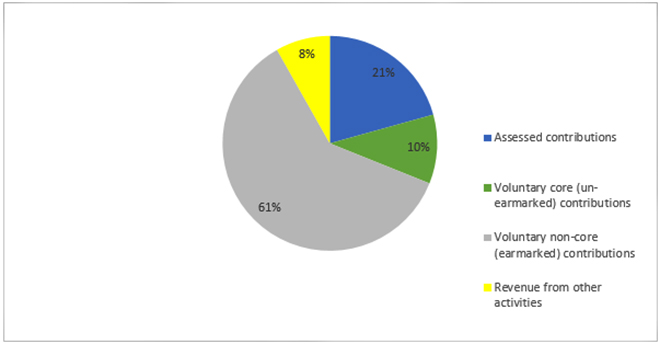

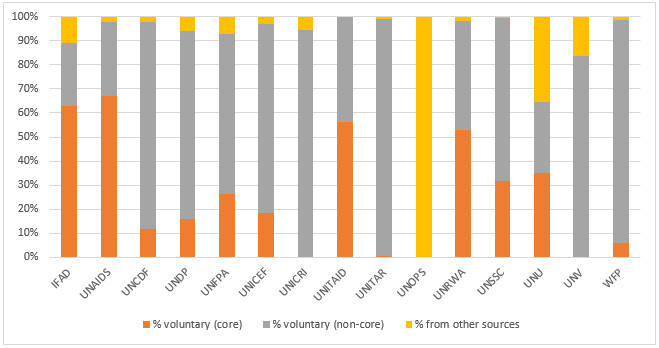

In 2021, voluntary contributions made up more than 70 percent of all revenue received by the UN system; the vast majority of these voluntary contributions were earmarked (Fig. 2). Moreover, a number of UN entities with important roles in the fields of sustainable development and humanitarian affairs, including the UN Development Programme (UNDP), the UN Children’s Fund (UNICEF) and the World Food Programme (WFP), do not receive any assessed contribution and rely entirely on voluntary funding (Fig. 3).

While UN budgets have historically struggled to meet costs, they face two crucial challenges that are exacerbated by the (potential) implications of geopolitical shifts. First, voluntary funding is increasingly unpredictable and in danger of falling prey to divisions among the UN membership as the provision or withholding of discretionary funds can easily be used for geopolitical purposes. Second, assessed contributions face the challenge of accruing major arrears, i.e. late payments. Some UN member states, including key providers, do not pay their dues on time or they pay only in part, thus undermining UN planning and disbursement processes. Publicly available data suggests that for some UN entities, cumulative arrears come close to or exceed the entire amount of assessed contributions due in a given year (Fig. 4). Overall, however, the reputational costs of slashing voluntary funds are arguably minor, compared with those of unilaterally withholding membership fees, making the latter a key tool for attempts to strengthen multilateral funding structures.

Fig. 2. Voluntary Contributions in UN Funding (% of All Revenue Received by the UN System in 2021)

Source: Authors’ own, based on CEB data, accessed on 28 March 2023[8]

Source: Authors’ own, based on CEB data, accessed on 14 May 2023

Fig. 4. Cumulative Arrears (as Share of 2019 Assessed Contributions)

* Accumulated amounts of UN member states’ late payments

Source: Authors’ own, based on data from: UN General Assembly, “Budgetary and Financial Situation of the Organizations of the United Nations System,” 2020, A/75/373, published in Haug et al. “International Organisations and Differentiated Universality.”[9]

2. The G20’s Role

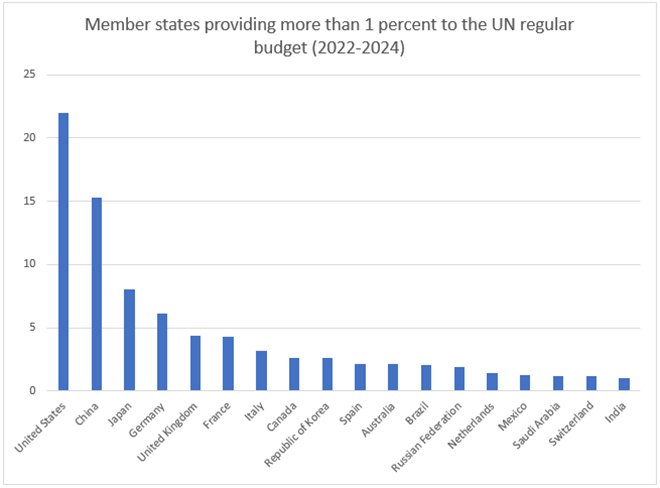

The G20 brings together 19 UN member states as well as the European Union (EU), representing a diverse group of global players. The G20 not only comprises key representatives from six continents, but it also includes the most important contributors to the UN regular budget. Eighteen states provide more than one percent of the UN regular budget each; 15 (or indeed 17) of them[a] are part of the G20 (Fig. 5). With this unique combination of (still limited) cross-continental representation and (considerable) economic weight, the G20 is a global forum that has the focus and the membership to forge an alliance among key global powers to meaningfully address mounting challenges to UN finances in an increasingly multipolar world.

Fig. 5. UN Scale of Assessments: Member State Contributions to the UN Regular Budget (2019–2021)

Source: Own elaboration, based on data in UN, “Scale of assessments for the apportionment of the expenses of the United Nations”, General Assembly Resolution A/RES/76/238, 2022.

Moreover, despite considerable evolution in the relative shares of key states at times, all G20 members have long been abiding by the formula used for calculating assessed contributions to UN budgets.[10] They have all also been part of a recent – and promising – turn in funding patterns at the World Health Organization (WHO). In 2022, WHO member states – including G20 members – agreed to incrementally triple the size of the organisation’s regular budget: by 2028, half of WHO’s budget should come in the form of assessed contributions.[11]

Thus, there seems to be considerable common ground across ideological and development-related divides to capitalise on this de facto consensus on burden-sharing in order to strengthen the reliability of UN funding flows and put the UN on a substantive financial footing. Member states, including G20 members, acknowledged in the 2018 Funding Compact, as part of the reform of the UN development system, that unreliable and inflexible funding is a key challenge for many UN entities.[12] While it is not the only measure required to better equip the UN to effectively address current and future crises, providing a sound funding base is an investment in a more capable and impartial world organisation.[13]

Overall, the G20 is uniquely positioned to seize the momentum triggered by the decision to gradually increase membership fees at WHO, and use it to strengthen the operative abilities and the strategic capacities of the UN by expanding member states’ assessed contributions.

3. Recommendations to the G20

The G20 members can reinforce multilateralism by strengthening and expanding the use of assessed contributions in the UN’s funding mix. This will also contribute to upholding commitments formulated in the Funding Compact, wherein UN member states pledged to increase the share of reliable core funding for UN entities.[14] The G20 has unique leverage on this as it not only collectively shoulders a large part of the UN’s bills, but also bridges the North-South divide, which persists among the most pronounced divisions in UN negotiations.

By reinvigorating assessed contributions, the G20 will send an important message to all UN member states that it accepts its financial and political responsibilities for multilateralism and is prepared, in times of multiple global crises, to invest both financial and political capital in placing the world organisation on a more sound financial foundation. While the heterogeneity of G20 members poses a challenge to identifying consensus over membership fee modalities at the UN, turning existing rivalries into a ‘race to the top’ for strong multilateralism will pay dividends for all. Overall, this Policy Brief suggests that a G20 proposal for UN reform should include the following:

(1) Raising assessed contribution levels

The G20 should advocate for increasing the use of membership fees, particularly for those UN entities where (often heavily) earmarked funds have outgrown assessed contributions. Building on the recent strategic funding shifts at WHO,[15] UN entities should define the core costs, deemed essential for their global governance activities, and stipulate the amount of money each member state must contribute according to the current Scale of Assessments to cover half of their overall annual budgets through assessed contributions.[16] This will allow stakeholders, including UN officials, observers, and pressure groups, to become familiar with what this alternative funding practice will look like. Overall, raising assessed contribution levels (i.e., enlarging regular budgets whose costs are distributed among member states according to the scale) will help ensure that UN core functions do not rely on discretionary and thus, often unpredictable funds.

(2) Expanding the use of assessed contributions

The G20 should lead the way in exploring the possibility of applying the Scale of Assessments to critical parts of the budgets of those UN entities that, so far, do not receive assessed contributions (Fig. 3). These organisations have a funding ratio skewed towards non-core resources even as they play an important role in global governance processes. According to the UN Chief Executives Board for Coordination, there are currently 13 UN bodies that do not receive assessed contributions. One is a Specialized Agency that has its own replenishment model [International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD)]; three are special entities [United Nations Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA), Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS), and United Nations Office for Project Services (UNOPS)]; four are funds and programmes [UNDP, United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), UNICEF, and WFP)]; and five are Related Organizations.[17] The four funds and programmes, in particular, heavily rely on non-core resources and obtain less than 25 percent of their revenue from voluntary core (i.e. un-earmarked) sources. At WFP, for instance, the share of earmarked funding stood at 91 percent in 2019. These figures indicate significant income instability and the need for substantial institutional efforts to cover core operational costs. The G20 can encourage these entities to, again, calculate and communicate the amount of money each member state will need to pay to cover half of each entity’s overall annual Budget, familiarising stakeholders with what this alternative funding approach will look like.

(3) Tweaking the formula

The G20 should discuss how the formula for assessed contributions can be made fit for a world of existential transnational challenges. To ensure that the remarkably stable[18] formula remains fit for purpose, the G20 member states should explore the possibility of adding indicators to the Scale of Assessments for specific UN bodies. Here, the premium on peace operation costs, provided by the Security Council’s five permanent members (all members of the G20 as well), serves as a case in point. While a fine balance needs to be found between mobilising resources and operationalising differences in capabilities and responsibilities, issue-specific variables – such as a state’s climate change vulnerability, carbon footprint or readiness to host refugees – can help in updating the Regular Budget formula of individual UN entities. Such dimensions can also introduce a merit-based element to the question of who absorbs the costs of global governance. More generally, a long-standing suggestion has revolved around spreading the costs across the UN membership more evenly and reducing the reliance on one member state, i.e. the US (and soon two, if China’s economic rise continues), by lowering the assessed contributions cap that currently stands at 22 percent. While any adjustment of the formula is likely to be controversial as it will shift the distribution of costs among member states at a time of extreme geopolitical sensitivity and fiscal constraint, the G20 is a key forum for exploring support for potential suggestions among the most influential global powers.[19]

(4) Incentivising on-time payments

Finally, the G20 should work towards further incentivising the payment of assessed contributions in full and on time. Here, some G20 members have a particularly key role to play. For instance, the US government, as the largest contributor to the UN regular budget, has often paid a share of its assessed contributions that is just high enough to ensure that it does not lose its voting rights in the General Assembly.[20] While member states with considerable arrears are in the minority, tightening formal sanctions for those who do not pay their assessed contributions or do not pay on time is difficult in the light of consensus-based decision-making procedures. Instead, the G20 should provide a venue among key contributors for agreeing on and implementing a roadmap for a more reliable payment of dues.

As a first step, G20 members should commit to meeting their financial obligations as a sign of support to UN multilateralism, and highlight this explicitly in speeches of heads of state and governments at the annual UN gathering in September. They should also ask for introducing more transparency across the UN so that system-wide data on arrears is easily accessible. This will provide the basis for a renewed discussion among member states on lowering the threshold for applying the only sanction that currently exists with regard to UN membership fees, namely the loss of voting rights. More effective incentive structures for decreasing arrears and increasing the level of on-time payment will not only reinforce the ability of UN bodies to carry out their work, but will also, more generally, strengthen the standing of assessed contributions as a stable and reliable multilateral funding mechanism.[21] Incentivising on-time payments, particularly among G20 members, will also contribute to boosting the payment morale in a highly volatile geopolitical context.

The authors thank colleagues from the Think 20 Task Force 7 for guidance, Nico Fricke for his research assistance, and two anonymous reviewers for feedback on an earlier draft of this Policy Brief.

Attribution: Sebastian Haug, Nilima Gulrajani and Silke Weinlich, “Funding Multilateralism: Strengthening the United Nations Through Assessed Contributions,” T20 Policy Brief, June 2023.

Endnotes

[a] The United States, China, Japan, Germany, the United Kingdom, France, Italy, Canada, the Republic of Korea, Australia, Brazil, the Russian Federation, Mexico, Saudi Arabia, India and, via the EU, Spain and the Netherlands.

[1] This Policy Brief builds on and draws from more detailed research on assessed contributions in the UN system and the notion of “differentiated universality”; Sebastian Haug, Nilima Gulrajani and Silke Weinlich, “International Organizations and Differentiated Universality: Reinvigorating Assessed Contributions in United Nations Funding,” Global Perspectives 3, no. 1 (2022): 39780; see also Nilima Gulrajani, Sebastian Haug and Silke Weinlich, “Fixing UN financing: a Pandora’s box the World Health Organization should open,” ODI Briefing/Policy Paper (2022); Silke Weinlich, Nilima Gulrajani and Sebastian Haug, “Re-discovering assessed contributions in the UN system: Underexploited, yet full of potential,” in Financing the UN Development System: Joint Responsibilities in a World of Disarray, eds. Dag Hammarskjöld Foundation and UN Multi-Partner Trust Fund Office (Uppsala: Dag Hammarskjold Foundation, 2022), 127-130.

[3] Ronny Patz and Klaus H. Goetz, Managing Money and Discord in the UN: Budgeting and Bureaucracy (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019).

[4] Haug, Gulrajani, and Weinlich, “International Organizations and Differentiated Universality”; see Global Policy Forum, “Tables and Charts on UN Regular Budget”, accessed 16 June 2021.

[5] Haug, Gulrajani, and Weinlich, “International Organizations and Differentiated Universality”.

[6] Silke Weinlich, Max Otto Baumann, Erik Lundsgaarde and Peter Wolff, Earmarking in the Multilateral Development System: Many Shades of Grey (Bonn: DIE Studies 101, 2020).

[7] Haug, Gulrajani, and Weinlich, “International Organizations and Differentiated Universality”; see Chief Executives Board, “Revenue by entity”, n.d..

[8] Un-earmarked funding includes the following categories: assessed contributions, voluntary (non-earmarked core) contributions, and income from other sources (earned directly by the UN entity, including from investments, exchange gains, etc.); revenue earned from services to/activities performed on behalf of other UN entities; and revenue earned from services to/activities performed on behalf of governments and others outside the UN system. Earmarked funding includes local resources, specific contributions to projects and programmes, revenue from global vertical funds, single agency thematic funds and UN interagency pooled funds, and in-kind earmarked contributions.

[9] Arrears can vary considerably from year to year; for the latest data, see UN General Assembly, “Budgetary and financial situation of the organizations of the United Nations system”, Resolution A/77/507, adopted on 5 October 2022.

[10] Haug, Gulrajani, and Weinlich, “International Organizations and Differentiated Universality”.

[11] Haug, Gulrajani, and Weinlich, “International Organizations and Differentiated Universality,” 14; Gulrajani, Haug, Weinlich, “Fixing UN financing”; Weinlich, Gulrajani, Haug, “Re-discovering assessed contributions”.

[12] On the Funding Compact, see UN General Assembly, Resolution A/RES/72/279, adopted on 31 May 2018.

[13] Other proposals on how to strengthen the UN are currently under debate to prepare the Summit of the Future in 2024; see Marianne Beisheim and Silke Weinlich, Germany and Namibia as Co‑leads for the United Nations. Chances and challenges on the road to the 2024 UN Summit of the Future. (SWP Comment no. 3, 2023), doi:10.18449/2023C03.

[14] The Funding Compact stipulates that the overall share of (voluntary) core funding should increase to a level of 30 percent of total funds provided to UN entities; see Bruce Jenks and Silke Weinlich, “Current and Future Pathways for UN System-Wide Finance,” in Financing the UN Development System: Time for Hard Choices, eds. U.N. Multipartner Trust Fund Office and Dag Hammarskjöld Foundation (Uppsala: Dag Hammarskjöld Foundation, 2019), 119–23.

[15] Gulrajani, Haug, Weinlich, “Fixing UN financing”; Weinlich, Gulrajani, Haug, “Re-discovering assessed contributions”; Haug et al., “International Organizations and Differentiated Universality”.

[16] A case in point here is the funding of the UN’s Resident Coordinator (RC) system: The website of the trust fund supporting the RC system lists the actual amounts member states would need to pay should the system be funded through assessed contributions – something the UN Secretary-General has long been advocating for; see UNSDG, “Where the funds are coming from: Voluntary Contributions”, accessed March 27 2023.

[17] Three training institutions—namely UNITAR, UNSSC, and UNU—as well as the UN Capital Development Fund (UNCDF) associated with UNDP and UNITAID, which is associated with WHO.

[18] Haug, Gulrajani, and Weinlich, “International Organizations and Differentiated Universality”.

[19] For a more detailed discussion of adding variables to the existing formula, see Haug, Gulrajani, and Weinlich, “International Organizations and Differentiated Universality”.

[20] Klaus Hüfner, In Love-Hate with the United Nations? The United States and the UN System (Berlin: Frank & Timme, 2019).

[21] One incentive-based model already used in a Specialized Agency—that, however, does not receive assessed contributions—is that of the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD), where voting rights on the governing council are partly determined by member states’ prompt payment in a given year, acting as a carrot that incentivises members’ payment morale with only partial adjustments to the principle of equal universal membership; see Haug, Gulrajani, and Weinlich, “International Organizations and Differentiated Universality”, 14-15.