Task Force 6: Accelerating SDGs: Exploring New Pathways to the 2030 Agenda

Inequitable vaccine distribution during the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly in low- and lower-middle income countries, has shown how market failures have hampered access to medical technologies. This brief identifies governance, financing, and regulation problems at the state, regional, and global levels that contribute to the market failure of medical technologies. The G20 is a viable avenue to find shared and effective solutions to encourage governments in adopting market-shaping strategies to meet the common objective of equitable access to medical technologies. Investing in research and development and expanding manufacturing facilities located in different regions worldwide are essential for the realisation of the common objective. Under the direction of a global governing entity and with allocations of funding and supportive regulations, these manufacturing facilities can serve as a pathway to sustain the production and distribution of medical technologies.

1. The Challenge

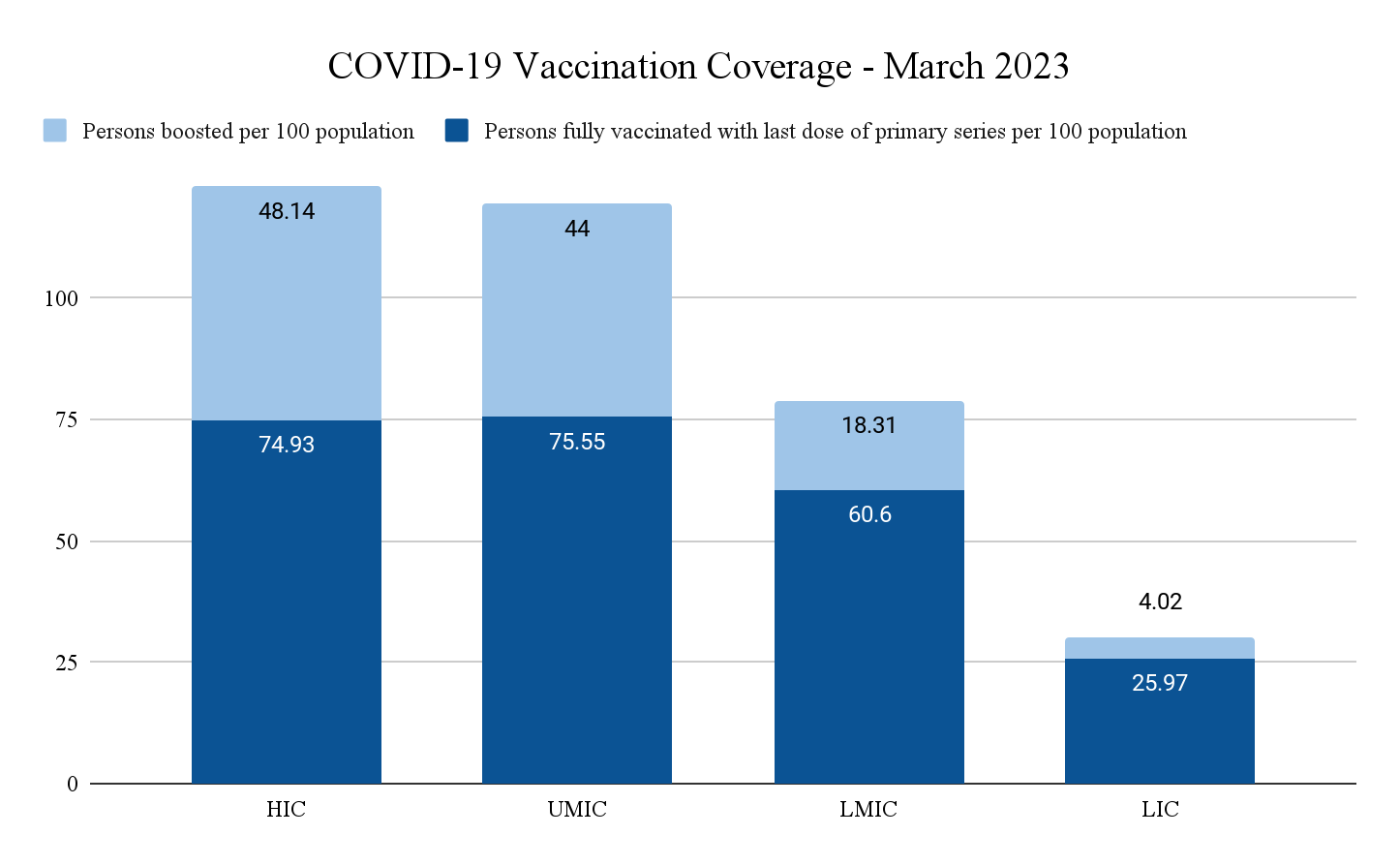

Medical technologies[a] refer to a broad range of health innovations. Globally, access to medical technologies is inequitable, with low-income countries (LICs) often having the least access. This was exemplified when LICs struggled to obtain COVID-19 testing kits[1] and medicines including the Paxlovid[2] during the pandemic. One notable case is the global COVID-19 vaccination rate. As of March 2023, only around 26 per 100 people in LICs have been fully vaccinated, in comparison with almost 75 per 100 people in high-income countries (HICs) (see Figure 1).[3]

Figure 1: COVID-19 vaccination coverage globally in March 2023

Source: Authors’ own based on WHO data[4]

In this brief, we elaborate how market failures that lead to inequitable access to medical technologies can happen at three levels—the state, regional, and global. Furthermore, we argue that market failures are caused by governance, financing, and regulations problems at each level.

Market Failures at the State Level

Ideally, governments as producers and regulators have the power to align stakeholders to scale up research and development (R&D) facilities for medical technologies, thus increasing access to the products.[7]

Governance: Not all states prioritised access to medical technologies. LICs spent around 6.2 percent of their public expenditure for health in 2020 compared to 14.3 percent in HICs, which partially explained the low national capacities in manufacturing medical technologies.[8] On the other hand, governments in HICs can misallocate healthcare spending by prioritising early stage and preclinical product development over advanced development.[9]

Financing: Different fiscal capacities might cause different spending for medical technologies. The World Health Organization (WHO) reported in April 2023 that the low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) and LICs spent only 0.01 percent and 0.02 percent of their gross domestic product (GDP) on health R&D expenditure, a far cry from HICs that spent 0.25 percent of their GDP.[10] In relation to the COVID-19 pandemic, LICs would need to increase 30 percent to 60 percent of their health expenditure to vaccinate 70 percent of their population, while HICs would only need to increase by 0.8 percent.[11]

Regulation: Regulations governing public–private partnerships (PPP) and deals can determine whether outcomes are accessible to many or few, exemplified by the US government’s use of Other Transaction Agreements (OTAs) for COVID-19 vaccine development, which prevented the government from granting compulsory licenses or permitting generic manufacture in case of exorbitant pricing.[12]

Market Failures at the Regional Level

In the case study of Southeast Asia, they did not have a collective mechanism to distribute medical countermeasures during a health emergency.

Governance: The absence of a coordinating mechanism at the regional level limits foresight and surveillance capacities. The absence of a regional collective mechanism such as a Regional Reserve of Medical Supplies has an impact on the absence of a safety net for countries with limited capacity.[13]

Financing: Investment to strengthen pandemic prevention, preparedness, and response (PPR) capacity at the Southeast Asian regional level has been minimal. In the most ideal scenario, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) requires almost US$500 million to cover for vaccine delivery alone, or at least around US$200 million for the least ideal scenario.[14] The financing gap for vaccine delivery in four countries accounts for more than US$120 million.[15]

Regulation: There was a lack of enforcement of regional regulations in Southeast Asia. It was only after the COVID-19 pandemic hit the region that ASEAN initiated the establishment of the ASEAN Centre for Public Health and Emerging Diseases (ACHPEED). It was established to serve as a genomics hub to strengthen pandemic PPR and other infectious diseases across the region and foster ASEAN’s solidarity and centrality to coordinate the operationalisation of the ASEAN Strategic Framework for Public Health Emergencies.

Market Failures at the Global Level

The LICs and LMICs have limited domestic production capacity, resulting in high dependency on other countries. For instance, 55 member states of Africa cumulatively consume a significant portion of the global vaccine supplies but contributes only 1 percent of production.[16]

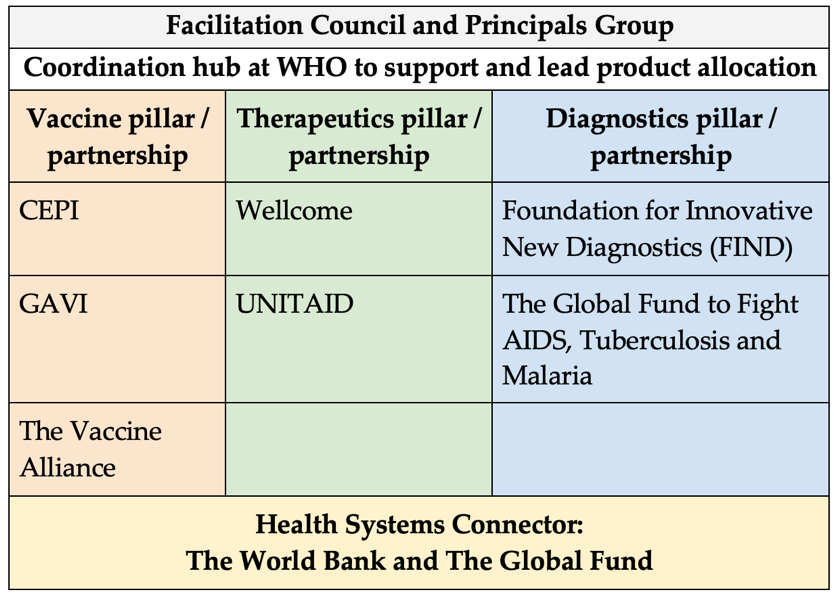

Governance: The Access to COVID-19 Tools (ACT) Accelerator (ACT-A) is a global body established during the pandemic to oversee the development and equitable distribution of medical technologies.[17] Some experts argued that ACT-A is inefficient, not inclusive enough, and underfunded.[18] Vaccine procurement and development was more prioritised—there was CEPI and COVAX under ACT-A, for example—while therapeutics and diagnostics received less attention.[19] ACT-A has allocated $16 billion out of $23.5 billion to its vaccine pillar, while only giving $1.8 billion for its therapeutics pillar.[20] The current ACT-A model (see Figure 2) is outlined here to outline its pillars and governance system.

Figure 2: The current ACT-A model

Source: Authors’ own, based on Moon et al.[21]

Regulation: Previous global regulations such as the 2005 International Health Regulations (IHR)[24] and the WTO Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS)[25] have not made it easier to transfer knowledge and technology from HICs to medical technologies manufacturers in LICs and LMICs.

The end result of market failures at all three levels is the inequitable distribution of medical technologies. To increase the access for new technologies, there needs to be a shift in the role of all governments from being market fixers to coordinators of all stakeholders to shape the market of medical technologies.[26] The G20, as a platform for discussion and partnerships of the global government leaders, can pave the way for this market shaping approach in ensuring equitable access to medical technologies.

2. The G20’s Role

The previous section underlined the market failures that lead to inequitable access to medical technologies as a global health challenge that needs to be addressed. We argue that the G20 serves as a viable opportunity to be an avenue in addressing and solving the challenge. There are two main reasons for this: the G20’s political commitment, and its inherent advantage as a multilateral platform.

At the G20 Summit 2021, G20 leaders promised to advance efforts to ensure timely, equitable, and universal access to safe, affordable, quality, and effective vaccines, therapeutics, and diagnostics (VTD) with particular regard to the needs of LICs and LMICs. They further recognised that vaccines are among the most important tools against the pandemic, and reaffirmed that extensive COVID-19 immunisation is a global public good.[27]

Recognising COVID-19 vaccines as a global public good will help establish concrete actions for more equitable and sustainable access to vaccines. The G20 leaders have promised to reinforce global strategies to support research and development and expand global vaccine manufacturing capacity at national and regional levels.

Secondly, the G20 has a comparative advantage as a multilateral platform. Dadush and Suominen argue that the G20 serves as an avenue of strategic coordination without heavy operational obligations, which allows it to have the flexibility to react quickly to events.[28] Additionally, the forum is small enough to allow concrete discussions for the promotion of public policies in response to global challenges, and yet it is large enough to represent the vast majority of the world population and economies.

In the context of global health, the German G20 Presidency 2017 and the Italian G20 Presidency 2021 introduced the establishment of a Health Working Group (HWG) and a Joint Finance Health Task Force (JFHTF), respectively. The former aims to enhance dedicated dialogue on important global health issues, and the latter to develop coordination arrangements between finance and health ministries to address pandemic prevention, preparedness, and response (PPR) issues.

Particularly after the COVID-19 pandemic exposed the crucial role of multilateralism in finding shared, effective solutions to global health challenges, global health became a pressing issue discussed in the G20. In 2022, the Indonesian G20 Presidency introduced a global health architecture agenda as a priority issue.[29]

A statement of intent from Argentina, Brazil, India, Indonesia, Saudi Arabia, South Africa, and Turkey to collaborate in creating VTDs manufacturing hubs was agreed upon during the Indonesian G20 Presidency in 2022. The statement of intent is particularly relevant and important, considering the oligopolistic nature of vaccine manufacturing that is concentrated in a smaller number of big pharmaceutical companies in HICs.

Addressing market failures will require countries to adopt market shaping strategies. In driving the demand and supply sides in LICs and LMICs, the G20 has a role in leveraging the statement of intent to a more concrete agreement, as the expansion of VTDs manufacturing hubs are critical to the market shaping agenda. The G20 is critical to ensuring that the plan in expanding VTDs manufacturing hubs is supported and followed up. We will present further recommendations on how the G20 can shape the market of medical technologies in the next section.

3. Recommendations to the G20

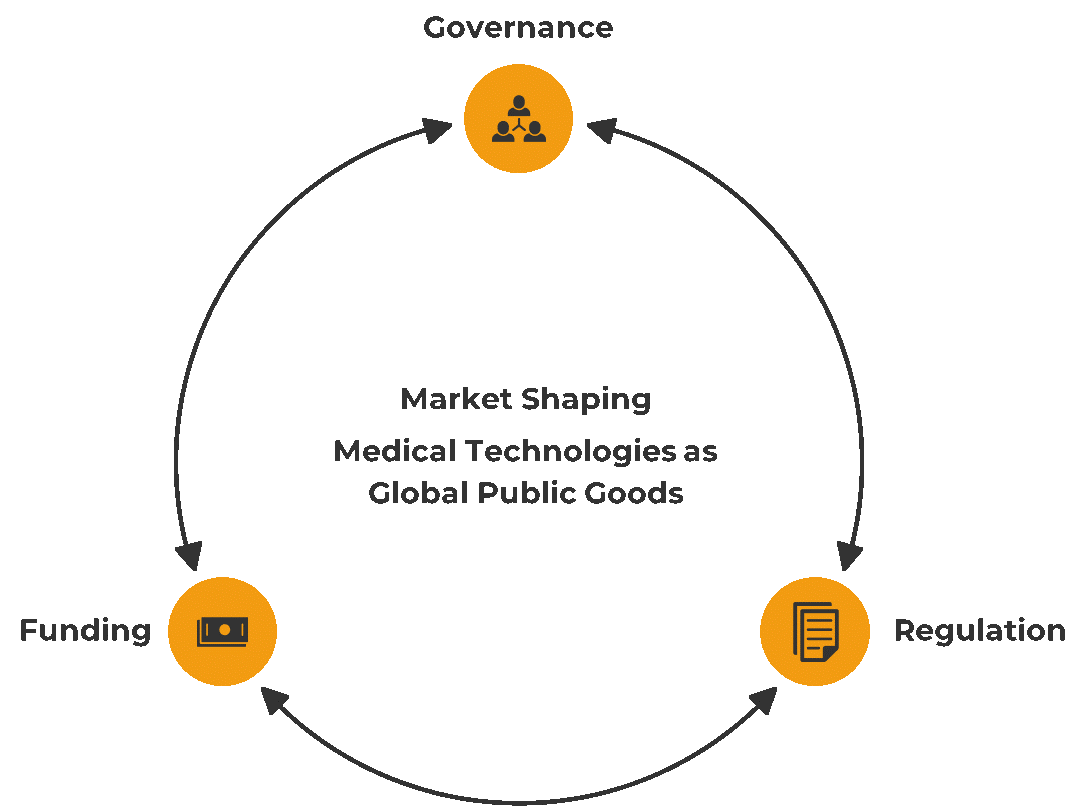

The G20 leaders need to adopt a long-term view and be more willing to reform the current governance structure, financing mechanism, and regulations (see Figure 3). The G20 members can consider implementing the following recommendations to shape the market to increase equitable access to medical technologies in their own countries and through regional and global collaborations.

Figure 3: Market shaping approach to increasing access to medical technologies

Source: Authors’ own

Market Shaping at the State Level: Increasing national capacity on producing medical technologies

Governance

- Set equitable and sustainable access to medical technologies as a national objective

The G20 leaders need to use a whole-of-government approach and direct all stakeholders to increase access to medical technologies by setting a common objective.[30] Medical technologies must be perceived as common goods. Governments must start shaping the market by involving the private sector and civil society in a bottom-up participatory national R&D prioritisation process to promote social ownership that is critical for accelerating medical technologies production and distribution.

- Assess the current national needs and capabilities on medical technologies

A clear mapping of the national needs and capacities can increase the efficiency of health expenditure allocation, including in prioritising R&D in neglected diseases. The R&D can also be supported from end to end, especially in the late-stage development and clinical trial phases widely implemented by the private sectors.

Financing

- Innovate to increase fiscal capacity and subsequent health expenditure

Member states need to innovate or join other innovative global financing mechanisms to expand domestic medical technologies R&D. Several options such as progressive taxation, eradication of corruption, and redirection of other sectors’ funds that are not compatible with health goals should be considered.[31] An example of innovative financing at the global level is the debt swap mechanism of Debt2Health initiative by the Global Fund, which counts creditor countries’ contributions to the Fund as the amount of debt that the creditor countries are willing to release, so that the debtor country can put all or a part of the released funds for health programmes in line with the Global Fund focus.[32]

Regulation

Optimise national regulations for collaborative partnerships in improving access to medical technologies To improve access to medical technologies, Governments need to create or reform regulations to allow public ownership. Publicly-funded R&D, including ones that are run by private companies, need to be regulated with conditionalities that benefit the public. Governments should be able to govern the knowledge created and the price of the end product to be proportionate to the investment.[33]

Market Shaping at the Regional Level

Governance

- The G20 can continue the realisation of the interregional VTD hubs

Regional-based governance mechanisms such as the African CDC need to be replicated in other regions. The WHO mRNA vaccine technology transfer hub model in South Africa and the 15 spokes that include some G20 member states can be the reference for other G20 VTD hubs.[34]

Financing

- The Pandemic Fund could channel its money to develop and strengthen ACPHEED, African CDC, or any other regional-based initiatives, through two scenarios:

- Regional proposal: The Pandemic Fund channels its money to the ASEAN COVID-19 Response Fund[b] as a regional pool of funds, which could be utilised to build a regional reserve of medical supplies (RRMS), including developing and strengthening the ACPHEED.

- Country proposal: The Pandemic Fund channels its money to an ASEAN member country that could utilise all or part of the money to develop and strengthen the ACPHEED. A current proposal being developed by Indonesia depicts this scenario.

Regulation

- Optimising the existing regulation within the regions. Accelerate the discussions on establishing relevant set of norms and regulations to strengthen regional cooperation

This would enhance continued flow of medical supplies and provision of relief supplies to medical facilities during emergency situations in the region. The objective is to achieve that through bilateral and multisectoral cooperation. Additionally, the RRMS mechanisms should be utilised to further support these efforts.

Market Shaping at the Global Level: Assigning a specific governance body that regulates directions and fundings to promote open sharing of innovation

Governance

- Affirm the role of ACT-A and increase its inclusivity

The ACT-A is the multistakeholder initiative that has received official support from the G20 Leaders in the Rome Declaration.[35] To optimise ACT-A, the G20 needs to reaffirm that ACT-A is the assigned entity to direct global access to medical technologies beyond the COVID-19 pandemic. To increase ACT-A efficiency, the G20 can push for a more transparent and clearer description of each stakeholders’ roles in ACT-A decision-making. To answer the global needs, ACT-A needs to include multiple civil society groups to represent multiple needs in the world. A regular forum and open public consultation can be held to ensure inclusive participation from populations most in need of medical technologies.[36]

Financing

- Raise the ACT-A funds: Increasing ACT-A funding is necessary. The G20 can help promote financing alternatives such as the Pandemic Fund and other development bank instruments to be directed towards ACT-A. For example, the World Bank can encourage multilateral funds under its trusteeship to include ACT-A as an eligible recipient. Also, the World Bank can help multilateral funds to release innovative financing instruments to support ACT-A.

- Consider the Global Public Investment framework: To reveal alternative global health financing resources, the Global Public Investment framework can be considered. With its principle of co-creation where all contribute and all benefit, each country, institution, and civil society organisation will make a contribution based on a proportional formula and are empowered as decision- makers through the global health agenda, particularly on this equitable VTD and R&D hub initiatives.

- Promote equitable and efficient allocation of ACT-A funds: First, the ACT-A funds need to be allocated for preventive and preparation measures. Funds should be allocated to develop medical technologies that allow the world to detect future outbreaks early, or to detect diseases that cause high burden early, thus ensuring that medical technologies R&D is not a reactive measure but a systematic preventative measure. Sustainable sources of funds are needed for achieving that goal. Second, when the fund has increased due to additional sources, ACT-A needs to allocate proportionately to all three pillars: the vaccine, therapeutics, and diagnostics pillars. [37]

Regulation

- Reform global regulations to enable an open model of medical technologies innovation system: Conditionalities in global contracts and treaties are needed to ensure that knowledge and technology are shared with those most in need. The G20 can play an important role in ensuring that the open sharing model of medical technologies R&D is supported in the proposed new Pandemic Treaty, an amendment of the 2005 IHR.[38] The G20 Leaders can promote the importance of Article 7 in the Zero Draft of the WHO convention, agreement, or other international instrument on pandemic PPR (Zero Draft of WHO CA+) which regulates states to comply with “promoting sustainable and equitably distributed production and transfer of technology and know-how.”[39]

Attribution: Clarissa Cita Magdalena et al., “From Market Failures to Market Shaping: Working Towards Equitable and Sustainable Access to Medical Technologies,” T20 Policy Brief, July 2023.

[a] These include, but not limited to, vaccines, therapeutics (medicines, pacemakers, implants), diagnostics (ECG monitor, reagents, test kits), protective equipment (masks, hazmat suits), spare parts for medical devices (semiconductor chips), and assistive technologies.

[b] ASEAN member countries have agreed to expand the ad-hoc fund into the ASEAN Public Health Emergencies Fund.

[1] Carolina Batista et al., ‘The Silent and Dangerous Inequity around Access to COVID-19 Testing: A Call to Action,”, eClinicalMedicine 43 ( January 1, 2022), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.101230.

[2] Gareth Iacobucci, “Covid-19: ‘Grotesque Inequity’ That Only a Quarter of Paxlovid Courses Go to Poorer Countries,” The British Medical Journal 379 ( November 21, 2022): o2795, https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.o2795.

[3] World Health Organization, “WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard,” World Health Organization, 2023.

[4] World Health Organization, “WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard,” World Health Organization, 2023.

[5] Mariana Mazzucato, Mission Economy: A Moonshot Guide to Changing Capitalism (Allen Lane, 2019).

[6] World Health Organization, Global Vaccine Market Report, World Health Organization, 2020.

[7] Mazzucato, Mission Economy: A Moonshot Guide to Changing Capitalism

[8] World Health Organization, Global Spending on Health: Rising to the Pandemic’s Challenges, World Health Organization,2022.

[9] Maria Elena Bottazzi and Peter J. Hotez, “‘Running the Gauntlet'”: Formidable Challenges in Advancing Neglected Tropical Diseases Vaccines from Development through Licensure, and a ‘Call to Action,’” Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics 15, no. 10 (October 3, 2019): pp 2235–42.

[10] World Health Organization, Gross Domestic R&D Expenditure on Health (Health GERD) as a % of GDP, World Health Organization, 2023.

[11] UNDP, Global Dashboard for Vaccine Equity, UNDP Data Futures Platform, 2023.

[12] Kathryn Ardizzone and James Love, “Other Transaction Agreements: Government Contracts that Eliminate Protections for the Public on Pricing, Access and Competition, Including in Connection with COVID-19 Vaccines and Treatments,” KEI Briefing Note, KEI, 2020.

[13] CSIS Indonesia, “COVID-19 in Southeast Asia: 10 Countries, 10 Responses,” CSIS Indonesia, November 16, 2022.

[14] Griffiths, Ulla, Ibironke Oyatoye, Jennifer Asman, Nikhil Mandalia, Logan Brenzel, Donald Brooks, and Stephen Resch. ‘Costs and Predicted Financing Gap to Deliver COVID-19 Vaccines in 133 Low- and Middle-Income Countries’. UNICEF, 2022.

[15] Griffiths, Ulla, Ibironke Oyatoye, Jennifer Asman, Nikhil Mandalia, Logan Brenzel, Donald Brooks, and Stephen Resch. ‘Costs and Predicted Financing Gap to Deliver COVID-19 Vaccines in 133 Low- and Middle-Income Countries’. UNICEF, 2022.

[16] Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunisation. “Why Africa needs to manufacture its own vaccines”. GAVI, July 2021.

[17] Katerini Tagmatarchi Storeng, Antoine de Bengy Puyvallée, and Felix Stein, “COVAX and the Rise of the ‘Super Public Private Partnership’ for Global Health,” Global Public Health 0, no. 0 (October 22, 2021): pp 1–17.

[18] Ann Danaiya Usher, “ACT-A: ‘The International Architecture Did Not Work for Us’” The Lancet 400, no. 10361 (2022): pp 1393–94.

[19] Nicole Lurie, Gerald T Keusch, and Victor J Dzau, “Urgent Lessons from COVID 19: Why the World Needs a Standing, Coordinated System and Sustainable Financing for Global Research and Development,” The Lancet 397, no. 10280 (March, 2021): pp 1229–36.

[20] Usher, “ACT-A”

[21] Suerie Moon et al., “Governing the Access to COVID-19 Tools Accelerator: Towards Greater Participation, Transparency, and Accountability,” The Lancet 399, no. 10323 (January 29, 2022): pp 487–94.

[22] John-Arne Røttingen et al., “Mapping of Available Health Research and Development Data: What’s There, What’s Missing, and What Role Is There for a Global Observatory?” The Lancet 382, no. 9900 (October 2013): pp 1286–1307.

[23] Mariana Mazzucato, “A Collective Response to Our Global Challenges: A Common Good and ‘Market-Shaping’ Approach,” Working Paper, UCL, 2023.

[24] Jeffrey D. Sachs et al., “The Lancet Commission on Lessons for the Future from the COVID-19 Pandemic,” The Lancet 400, no. 10359 (October 8, 2022): pp 1224–80.

[25] Frederick M. Abbott and Jerome H. Reichman, “Facilitating Access to Cross-Border Supplies of Patented Pharmaceuticals: The Case of the COVID-19 Pandemic,” Journal of International Economic Law 23, no. 3 (November 10, 2020): pp 535–61.

[26] Mariana Mazzucato and Josh Ryan-Collins, “Putting Value Creation Back into ‘Public Value’: From Market-Fixing to Market-Shaping,” Journal of Economic Policy Reform 25, no. 4 (October 2, 2022): pp 345–60.

[27] G20, G20 Rome Leaders’ Declaration, G20, 2021.

[28] Uri Dadush and Kati Suominen, “Is There Life for the G20 beyond the Global Financial Crisis?” Journal of Globalization and Development 2, no. 2 (January 25, 2012).

[29] Pramudyani, Yashinta Difa. ‘Strengthening Global Health Architecture through G20 Forum’. Antara News, 20 June 2022, sec. Indonesia.

[30] Els Torreele et al., “It Is Time for Ambitious, Transformational Change to the Epidemic Countermeasures Ecosystem,” The Lancet 401, no. 10381 (March, 2023): pp 978–82.

[31] Torreele et al.

[32] The Global Fund, “Debt2Health – Collaboration Through Financial Innovation,“.

[33] Mazzucato, Mission Economy: A Moonshot Guide to Changing Capitalism

[34] “Why a Vaccine Hub for Low-Income Countries Must Succeed,” Nature 607, no. 7918 (July 13, 2022): pp 211–12.

[35] G20, G20 Rome Leaders’ Declaration, G20, 2021.

[36] Suerie Moon et al., “Governing the Access to COVID-19 Tools Accelerator: Towards Greater Participation, Transparency, and Accountability,” The Lancet 399, no. 10323 (January 29, 2022): pp 487–94.

[37] Moon et al.

[38] Roland Alexander Driece et al., “A WHO Pandemic Instrument: Substantive Provisions Required to Address Global Shortcomings,” The Lancet 0, no. 0 (April 4, 2023).

[39] World Health Organization, Zero Draft of the WHO CA+ for the Consideration of the Intergovernmental Negotiating Body at Its Fourth Meeting, World Health Organization, February 2023.