Task Force 6: Accelerating SDGs: Exploring New Pathways to the 2030 Agenda

The polycrisis of the climate emergency, the COVID-19 pandemic, and the war in Ukraine have reversed many countries’ gains in tackling food insecurity and malnutrition. In Brazil and India, access to a healthy diet made significant progress between the 2000s and the 2010s, with various social protection programmes central to achieving this. During the recent crises, both countries used social protection measures to maintain food security. The achievements of and challenges faced by both countries offer valuable lessons for other G20 countries. Key recommendations arising from these lessons include strengthening existing programmes and their foundation through legislation, unified registries, and minimum budget allocations, as well as tackling both food demand and supply.[a]

1. The Challenge

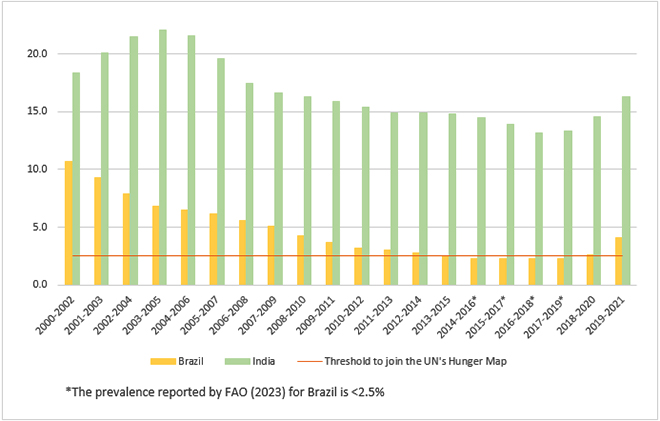

The G20 countries currently face several challenges towards achieving Sustainable Development Goal 2 in relation to nutrition and food security. The threat to food security was on the rise even before the COVID-19 pandemic due to climate change-induced droughts, unseasonal rains, and heightened temperatures. The pandemic then reversed several gains and amplified the deterioration of food security, further diminishing consumers’ ability to purchase food and disrupting value chains.[1],[2] Globally, an estimated 828 million people (10.5 percent of the world population) faced hunger in 2021, an increase of almost 210 million since 2019.[3] As the world recovered from the socioeconomic impacts of the pandemic, a new food security threat emerged as the war in Ukraine reduced food imports from Ukraine and Russia and increased prices. Brazil and India, two of the most populous G20 countries, have been significantly affected by this polycrisis. Despite their reduction in food insecurity in the 2000s and early 2010s through increased production, the prevalence of undernourishment began to rise again in the second half of the 2010s. Brazil’s trend changed course and began increasing in 2018-2020 (2.6 percent), while India’s did so a year earlier (13.3 percent) (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Prevalence of undernourishment in Brazil and India (%) (2000-2021)

Source: FAOSTAT 2023[4]

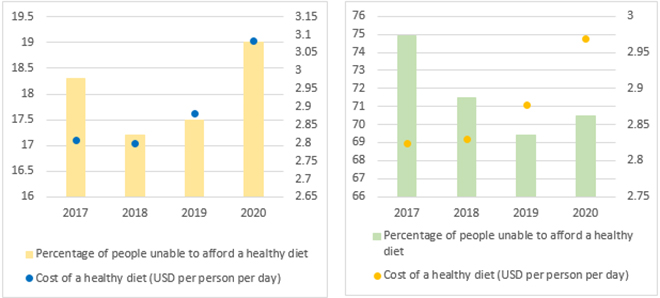

Figure 2: Health diet affordability – Brazil (2017-2020) |

Figure 3: Health diet affordability – India (2017-2020) |

e |

|

Source: FAO et al. 2022[5] Source: FAO et al. 2022[6]

Addressing malnutrition among women and children

Addressing malnutrition requires a special focus on women and children. The first 1,000 days of a child’s life are a crucial period for brain development[7] and inadequate access to nutrition in pregnant women and children has dire consequences that persist into adulthood.[8] Further, causes of undernutrition such as access to food, care, water, sanitation, and health services[9] are determined by the status of women, and the related social, economic, and political situation, and structures that they are situated within.

Social protection measures that directly address malnutrition, and indirect measures that have a bearing on household income and food security are thus crucial. Cash- and in-kind transfers and labour market policies, as well as ‘cash plus’ interventions can support families in overcoming monetary and non-income barriers to meeting their nutritional needs.[10],[11],[12]

2. The G20s Role

Brazil and India can offer important lessons in how to support food security and nutrition during crises through large social protection programmes.

Lessons from Brazil

· Before the polycrisis

In 2003, Brazil’s Zero Hunger Strategy was applied as a social policy framework.[13] However, the attention paid to combat food insecurity decreased in the 2010s, culminating in the reversal of several achievements illustrated above. Established under the Zero Hunger Strategy in 2003, Brazil’s Food Acquisition Programme (PAA) supports food demand and supply by purchasing food and seeds from farmers and distributing it as in-kind transfers.[14] The PAA’s instant donation modality increased both the diversity and the gross value of agricultural production of its beneficiaries.[b] This increased farmers’ incomes, allowing them to further invest in their production, and to produce more diverse and sustainable goods, supporting their own nutritional status as well as of those who receive their produce.[15] However, the PAA faced payment delays and challenges in reaching the most vulnerable farmers.[16] Further, budget cuts resulted in an 82.8 percent decrease in PAA acquisitions during the period 2011-2019.[17]

The National School Feeding Programme (PNAE), created in 1954 covers around 40 million students.[18] In 2009, influenced by the PAA, the PNAE determined that at least 30 percent of its food resource be procured from family farmers.[19] Unlike the PAA, which is based on a decree, the PNAE established this change through statutory legislation, with more legal strength.[20],[21] However, the uptake of this new rule by municipalities has been heterogenous and the share of family farmers as suppliers only reached 22 percent in 2017.[22]

Brazil’s conditional cash transfer programme Bolsa Família or “family bag” (PBF) was implemented in 2003 with the aim of mitigating poverty and fomenting access to health and education, unifying four existing cash transfers.[23],[24] Impact evaluations found that the PBF had increased household expenditure on food, increasing the availability of fresh, diverse ingredients, but did not significantly improve beneficiaries’ nutritional status.[25],[26],[27]

· Brazil’s response to the pandemic

The pandemic amplified the deterioration of Brazil’s food security.[28] The national social protection response addressed both food suppliers and consumers, with more emphasis on the latter. The bulk of measures benefitted food demand by transferring either cash (eight interventions), or in-kind benefits (two interventions), or by providing other forms of support such as deferral of taxes or subsidies (10 interventions).[29]

Four major social protection programmes focussed on food supply during the pandemic response, all of which already existed. Among these were the PAA—renamed Feed Brazil Programme (PAB)—and the PNAE, both limited in their abilities to support family farmers, as will be explained below. The other two programmes[c] only covered around 680,000 family farmers during the 2019-20 harvest. The PAB was modified in 2021, losing its seed purchase modality,[30],[31] but remained in place during the pandemic.

However, by June 2022, while around 33 million Brazilians were hungry, just 11,460 tons of food had been donated through PAB, as compared to 114,043 tons in 2021. By August 2022, just around a fifth of municipalities had received enough federal funds to execute purchases.[32] A budget injection for PAB of around BRL 500 million shortly before the 2022 elections[33] came too late, given the time needed for the approval of fund execution and for food purchases and deliveries. Due to the previous budget cuts, farmers could not finance their production and were unable to supply food for the undernourished, essentially ending the PAB.[34]

The PNAE continued delivering meals to students despite the shift to remote education by delivering food directly to families. However, irregularities in its implementation resulted in the consumption of ultra-processed foods and lack of income for family farmers in some municipalities, as the produce of these farmers was not purchased or was lost.[35],[36]

The PBF remained in place during the pandemic but was rebranded Brazil Aid. It included around 1.2 million additional families from its waiting list and waived conditionalities. By May 2021, 14.3 million families were covered, facilitated by the CadÚnico, Brazil’s single registry that provides data on poor families to several social protection programmes. This meant families did not need to apply.[37],[38]

The most notable of the emergency programmes was the Emergency Aid, a monthly cash transfer to informal and self-employed workers, and the unemployed. The benefit amount decreased from the initial BRL 600 transfer in 2020 to BRL 150 in 2021.[d],[39] It too relied on the CadÚnico to identify its beneficiaries, but others, who were not yet in CadÚnico, had to register separately through a mobile app, posing an access barrier to those unable to use digital technology.[40]

· Food insecurity persists

The above-mentioned measures were not enough to contain the impact of the Covid-19 crisis on food insecurity in Brazil.[41] Among households with children under the age of 10, the prevalence of hunger doubled between 2020 (9.4 percent) and 2022 (18.1 percent). Considering households with members up to the age of 18, this rate rose to 25.7 percent in 2022.[42]

With Lula’s return Brazil’s presidency in January 2023, hunger is once again a political priority. Examples include an increase in up to 39 percent of federal funds transferred to municipal governments for school meals under the PNAE.[43] The PAA has also been reintroduced in March 2023. Next to the return of funds to purchase goods from family farmers at market prices, indigenous, and quilombola[e] producers are to have easier access to the programme, and women from occupations pushing for agrarian reform are to be prioritised.[44]

Lessons from India’s response

· Before the polycrisis

The Public Distribution System (PDS) was reformed into a targeted scheme in 1997 to provide foodgrains at affordable rates. There were however major targeting errors in identifying the poor.[45] During the mid- to late 2000s, several state governments introduced PDS reforms, including near universalisation, improved the delivery system through digital technologies, and inttroduced transparency and accountability measures.[46] The National Food Security Act (NFSA), 2013 expanded PDS coverage to around two-thirds of the population[47] (earlier coverage under the central scheme was towards a poor population of about 36 percent). The PDS has contributed to basic food security,[48] but has showed up a need to address potential risk of leakages (a declining trend)[49] and distributing beyond cereals.

The NFSA includes a ‘priority’ ration card for subsidised foodgrains of 5 kgs per person per month for 75 percent of the rural and 50 percent of the urban population, currently covering about 800 million persons. The NFSA also entitles all children under the age of 14 to one free meal every working day through schools and Anganwadis, a cash transfer for pregnant women, and supplementary nutrition for pregnant and lactating women.

The Supreme Court orders in 2001 universalised the school mid-day meal scheme and integrated child development services (ICDS). Consequently, all children aged six to 14 in government schools, every child under the age of six, and all pregnant and lactating women were entitled to free meals and supplementary nutrition.[50] Anganwadi centres through which ICDS services are provided were expanded to cover all villages and urban slums. The ICDS also provides other services such as growth monitoring and nutrition counselling, forming the cornerstone for all the nutrition initiatives in the country.

The Pradhan Mantri Matru Vandana Yojana provides a cash benefit of INR 5,000 to all pregnant women for their first pregnancy. Under the National Social Assistance Programme elderly, single women, and persons with disabilities are provided a monthly pension. While these schemes are useful, they also require improvements in coverage, adequacy, and inflation-indexing.[51]

Further, the Mahatma Gandhi National Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA) provides 100 days of employment to all rural households on demand. India therefore supports food security along the life course through either cash or in-kind transfers.

· Response to the pandemic

India’s response to the pandemic was guided by two social protection legislations, MGNREGA (2005) and NFSA (2013), giving it the advantage of existing response mechanisms, which could be used for immediate action.[52] The entitlements provided under these legislations have a long history in India, as they were based on welfare schemes implemented since the 1970s. Some of these schemes first became legal entitlements due to the directions of the Supreme Court in 2001 in response to a Public Interest Litigation on the right to food.[53]

During the pandemic, these programmes were expanded, and the subsidised grains component of the NFSA increased to 10 kgs per person per month for almost two years. Meals for children were provided either as take-home rations in kind or as cash transfers.[54] The number of MGNREGA participants increased from an average of about 75 million persons per year in the previous five years to 112 million persons in 2020-21 and 106 million persons in 2021-22.[55]

Moreover, some short-term cash transfers were implemented, such as to beneficiaries of the social security pensions provided by the state, to poor women and, in some regions, to some occupation groups such as construction workers and taxi drivers.[56] While these were mostly one-time payments or lasted for only a couple of months, the NFSA and NREGS were more regular.

Several evaluations showed that these measures are effective in increasing food security,[57] enhancing school enrolment,[58] tackling severe malnutrition,[59] arresting distress migration,[60] and increasing rural wages.[61] Therefore, they have had an impact on malnutrition directly and indirectly. Although there have not yet been nation-wide systematic evaluations of the pandemic response, several field studies[62],[63] showed that these schemes made a substantial contribution towards compensating for the income lost due to the pandemic.[64] However, despite these benefits, food insecurity reportedly increased as compared to pre-pandemic levels.

· Pandemic highlights pre-existing challenges

Most gaps in the delivery of these programmes existed since before Covid-19. Coverage gaps were seen especially among the urban poor. Underfunding still results in poor quality of nutrition provided to children. Cash that replaced in-kind transfers was not sufficient for a family to afford even one healthy meal for one child.[65] This was further exacerbated by stagnant budgets for child feeding programmes (in nominal terms) and declining in real terms over the last eight years.[66] The maternity entitlements also are not inflation indexed and therefore their real values have been declining.

The poor quality of diets and the unaffordability of healthy diets has been another cause for concern. Estimates show that about 70 percent of the population cannot afford a healthy diet in India.[67] These statistics also raise the issue of going beyond the direct food entitlement schemes towards a decentralised and equitable food system.

3. Recommendations to the G20

These experiences highlight how political will is central to mitigating malnutrition, manifested especially in the allocation of funding and legally enshrining and enforcing regulations for programmes tackling food insecurity.

Working with family farmers can ensure access to healthy diets and improve living standards of small-scale producers. This is important because, while cash transfers and school meals can enhance access to food, the type of food that is consumed matters. Only a healthy diet can provide diverse nutrients, resulting in better health conditions. This requires a comprehensive approach, cutting across different ministries and departments.

The following recommendations can be drawn from this:

- Strengthen existing programmes

These could be cash transfers, in-kind transfers, and a combination of the two in most cases. Next to the injection of funds and using legal instruments, strengthening of existing programmes also entails the usage of integrated registries that can quickly identify potential beneficiaries.

- Link food supply and demand

Enshrine the procurement of in natura food from local, small-scale producers in statutory legislation and ensure its enforcement for social protection.

- Locate the problem of malnutrition within the larger framework of universal social protection

This is vital to address its multisectoral drivers.

- Spend a minimum proportion of GDP on nutrition-sensitive social protection

Set a minimum agreed standard for budgeting in statutory legislation. For example, the Incheon Declaration sets a target of allocating at least 4-6 percent of GDP to education,[68] and the eThekwini Declaration commits to a minimum of 0.5 percent of GDP for sanitation and hygiene programmes.[69]

Attribution: Beatriz Burattini and Dipa Sinha, “Food-Focused Social Protection Measures Before and During the Global Polycrisis: The Brazil and India Experience,” T20 Policy Brief, July 2023.

[a] The authors would like to thank Fábio Veras Soares (Director of International Studies, DINTE/IPEA), Gabriela Perin (Researcher, IPCid/IPEA), Elizabeth Harrop, Veena Bandyopadhyay (Social Protection Specialist, UNICEF India), and Hyun Hee Ban (Chief, Social Policy, UNICEF India) for their contributions to this policy brief.

[b] Estimated average increase of agricultural production by 13.2 percent to 56.8 percent among those of the tenth income quantile.

[c] Garantia Safra and PROAGRO.

[d] Different benefit amounts for different beneficiary groups.

[e] This term is not typically translated and refers to self-attributed ethnic groups with historically specific relations to territories, state oppression and ancestry (see Centro de Excelência contra a Fome. School Feeding in Traditional Communities: The quilombola PNAE. Brasília: World Food Programme. 2021).

[1] Regina Helena Rosa Sambuichi et al., Contribuições do Programa de Aquisição de Alimentos para a Segurança Alimentar e Nutricional no Brasil (Brasília: Institute of Applied Economic Research, 2022);

[2] Camila Rolon et al., ‘Social Protection Response to COVID-19 in Rural LAC: Social and Economic Double Inclusion’ (IPCIG, 2022).

[3] “Suite of Food Security Indicators, FAOSTAT, last modified July 12, 2023, https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/FS.

[4] FAOSTAT, “Suite of Food Security Indicators.”

[5]Camila Rolon, Beatriz Burattini, Lucas Sato et al., Social Protection Response to COVID-19 in Rural LAC (Brasília: International Policy Centre for Inclusive Growth, 2022) ; FAO et al., Regional Overview of Food Security and Nutrition – Latin America and the Caribbean: Towards improving affordability of healthy diets (Santiago: FAO, 2023), https://doi.org/10.4060/cc3859en.

[6] FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP and WHO, The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2022 (Rome: FAO, 2022).

[7] Sarah Cusick and Michael K. Georgieff, “The First 1,000 Days of Life: The Brain’s Window of Opportunity,” UNICEF, April 12, 2013, https://www.unicef-irc.org/article/958-the-first-1000-days-of-life-the-brains-window-of-opportunity.html.

[8] UNICEF, Birth through 6 Years (UNICEF, 2011).

[9] UNICEF, Conceptual Framework on Maternal and Child Nutrition (New York: UNICEF, 2021), https://www.unicef.org/media/113291/file/UNICEF%20Conceptual%20Framework.pdf.

[10] “Recommendation R202 – Social Protection Floors Recommendation, 2012 (No. 202),” ILO, last modified June 14, 2012, https://www.refworld.org/pdfid/5c77a49f7.pdf.

[11] Enrique Valencia Lomelí, “Conditional Cash Transfers as Social Policy in Latin America: An Assessment of Their Contributions and Limitations,” Annual Review of Sociology 34, no. 1 (2008): 475–99.

[12] International Policy Centre for Inclusive Growth, Social Protection: Meeting Children’s Rights and Needs, Policy In Focus 43 (Brasília: International Policy Centre for Inclusive Growth, 2018).

[13] RN da Silva et al., “Experiências dos programas de alimentação escolar: um estudo bibliométrico,” Diversitas Journal 6, no. 2 (2021): 2810–26.

[14] Burattini et al., Social Protection Response to COVID-19 in Rural LAC.

[15] Sambuichi et al., Impactos do programa de aquisição de alimentos sobre a produção dos agricultores familiares (Brasília: Institute of Applied Economic Research (IPEA), 2022), http://repositorio.ipea.gov.br/bitstream/11058/11615/1/TD_2820_Web.pdf.

[16] Danuta Chmielewska and Darana Souza, Food Security as a Pathway to Productive Inclusion: Lessons from Brazil and India (Brasilia: International Policy Center for Inclusive Growth, 2015), https://ipcig.org/publication/26790?language_content_entity=ar

[17] Sambuichi et al. Contribuições do Programa de Aquisição de Alimentos para a Segurança Alimentar e Nutricional no Brasil.

[18] Alexandre Arbex Valadares et al., Da regra aos fatos: condicionantes da aquisição de produtos da agricultura familiar para a alimentação escolar em municípios brasileiros (Brasília: Institute of Applied Economic Research, 2022), https://portalantigo.ipea.gov.br/portal/images/stories/PDFs/TDs/220128_td_2728.pdf.

[19] Chmielewska and Souza, Food Security as a Pathway to Productive Inclusion.

[20] Gabriela Perin et al., A evolução do programa de aquisição de alimentos: uma análise da sua trajetória de implementação, benefícios e desafios (Brasília: Institute of Applied Economic Research, 2021), https://repositorio.ipea.gov.br/handle/11058/10824.

[21] Mauro de Rezende Lopes and Armando Fornazier, “Modalidades de compras públicas de alimentos da agricultura familiar no Brasil,” Série Políticas Sociais e de Alimentação 2 (2016).

[22] Valadares et al., Da regra aos fatos.

[23] WWP, Ficha-Resumo Do Programa Bolsa Família (PBF) (WWP, 2015), http://wwp.org.br/publicacao/ficha-resumo-do-programa-bolsa-familia/.

[24] “Bolsa Familia, Programmes,” socialprotection.org, last modified October 1, 2019, https://socialprotection.org/discover/programmes/bolsa-familia.

[25] Fábio Veras Soares, Rafael Perez Ribas, and Rafael Guerreiro Osório, “Evaluating the Impact of Brazil’s Bolsa Família: Cash Transfer Programs in Comparative Perspective,” Latin American Research Review 45 (2) (2010) : 173–90. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0023879100009390.

[26] Ana Paula Bortoletto Martins, and Carlos Augusto Monteiro, “Impact of the Bolsa Família Program on Food Availability of Low-Income Brazilian Families: A Quasi Experimental Study,” BMC Public Health 16 (1) (2016) : 827, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-3486-y.

[27] José Anael Neves et al., “The Brazilian Cash Transfer Program (Bolsa Família): A Tool for Reducing Inequalities and Achieving Social Rights in Brazil,” Global Public Health 17 (1) (2022) : 26–42, https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2020.1850828.

[28] Sambuichi et al., Contribuições do Programa.

[29] “Social Protection Responses to COVID-19 on the Global South: Online Dashboard,” International Policy Centre for Inclusive Growth (IPC-IG), accessed July 21, 2023, https://socialprotection.org/social-protection-responses-covid-19-global-south.

[30] IPC-IG, “Social Protection Responses to COVID-19 on the Global South: Online Dashboard.”

[31] Sambuichi et al. Contribuições do Programa.

[32] Gabriel Croquer, “Esvaziado, programa federal de aquisições de alimentos vê doações despencarem,” G1, November 12, 2022, https://g1.globo.com/economia/agronegocios/noticia/2022/11/12/esvaziado-programa-federal-de-aquisicoes-de-alimentos-ve-doacoes-despencarem.ghtml.

[33] “PEC Kamikaze: Entenda,” G1, last modified, July 26, 2022,

https://g1.globo.com/politica/stories/2022/07/26/pec-kamikaze-entenda.ghtml.

[34] Camila Turtelli, “Com escalada de fome no Brasil, governo destrói programa alimentar,” UOL, June 6, 2022,

[35] Adriana Amâncio, ‘No Semiárido, Suspensão e Mudanças No Pnae Durante a Pandemia Afetam à Saúde e o Bolso’, 17 September 2021, https://www.asabrasil.org.br/noticias?artigo_id=11207.

[36] De Freitas, ‘Execução do PNAE durante a pandemia do COVID -19: oferta de alimentos’ (bachelorThesis, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, 2022), https://repositorio.ufrn.br/handle/123456789/48625.

[37] Direito, Denise and Cláudio Machado. “The Brazilian Single Registry in a Post-Pandemic Scenario: Opportunities and Challenges of Digitalisation.” Policy in Focus 19, no. 1 (2022): 30 – 32. International Policy Centre for Inclusive Growth.

[38] IPC-IG Online Dashboard.

[39] IPC-IG Online Dashboard.

Denise Direito and Machado Cláudio, “The Brazilian Single Registry in a Post-Pandemic Scenario: Opportunities and Challenges of Digitalisation,” Is Going Digital the Solution? Evidence from Social Protection, Policy in Focus, 19, no. 1 (2022): 30–32, https://ipcig.org/publication/31866?language_content_entity=en.

[41] Fundação Maria Cecilia Souto Vidiga, Desigualdades e Impactos Da Covid-19 Na Atenção à Primeira Infância (UNICEF: 2022), https://www.unicef.org/brazil/media/20221/file/desigualdades-e-impactos-da-covid-19-na-atencao-a-primeira-infancia.pdf.

[42] “2o Inquérito Nacional sobre Insegurança Alimentar no Contexto da Pandemia da Covid-19 no Brasil,” Rede Brasileira de Pesquisa, 2022, https://pesquisassan.net.br/2o-inquerito-nacional-sobre-inseguranca-alimentar-no-contexto-da-pandemia-da-covid-19-no-brasil/

[43] “Centro de Excelência do WFP celebra o reajuste dos valores da alimentação escolar no Brasil,” Centro de Excelência contra a Fome, March 17, 2023, https://centrodeexcelencia.org.br/centro-de-excelencia-do-wfp-celebra-o-reajuste-dos-valores-da-alimentacao-escolar-no-brasil/.

[44] “Retomada Do PAA Visa Fortalecer a Agricultura Familiar e a Garantir o Acesso à Alimentação Saudável a Todos Os Brasileiros,” CONAB, last modified March 22, 2023, https://www.conab.gov.br/ultimas-noticias/4947-retomada-do-paa-visa-fortalecer-a-agricultura-familiar-e-a-garantir-o-acesso-a-alimentacao-saudavel-a-todos-os-brasileiros.

[45] Reetika Khera, “Trends in diversion of PDS grain,” Economic and Political Weekly, 46(21) (2011): 106-114, http://www.jstor.org/stable/23017233.

[46] Avinash Kishore, and Suman Chakrabarti, “Is more inclusive more effective? The ‘New Style’public distribution system in India,” Food Policy 55 (2015): 117-130, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2015.06.006.

[47] Sayan Chakraborty and SP Sarmah, “India 2025: the PDS and national food security act 2013,” Development in Practice 29, no. 2 (2019): 230-249, https://doi.org/10.1080/09614524.2018.1527290

[48] Sudha Narayanan, and Nicolas Gerber, “Social safety nets for food and nutrition security in India,” Global food security 15 (2017): 65-76, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gfs.2017.05.001

[49] Khera, “Trends in diversion of grain,” 106 – 114.

[50] Lauren Birchfield and Jessica Corsi, “The right to life is the right to food: People’s Union for Civil Liberties v. Union of India & others,” Human Rights Brief 17, no. 3 (2010): 3.

[51] Jean Drèze and Reetika Khera, “Recent social security initiatives in India,” World Development 98 (2017): 555-572, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2017.05.035

[52] Dipa Sinha, “Hunger and food security in the times of Covid-19,” Journal of Social and Economic Development 23, no. Suppl 2 (2021): 320-331, https://doi.org/10.1007/s40847-020-00124-y

[53] Guha-Khasnobis and Vivek, The rights-based approach to development: Lessons from the right to food movement in India (London: Palgrave Macmillan UK, 2007).

[54] Guha-Khasnobis and Vivek, “Rights-based approach,” 308 – 327.

[55] “The Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act 2005,” Ministry of Rural Development, Government of India, accessed April 1, 2023, https://nrega.nic.in/MGNREGA_new/Nrega_home.aspx

[56] Sohini Sengupta and Manish K Jha, “Social policy, COVID-19 and impoverished migrants: challenges and prospects in locked down India,” The International Journal of Community and Social Development 2, no. 2 (2020): 152-172, https://doi.org/10.1177/2516602620933715

[57] Himanshu and Abhijit Sen, “In-kind food transfers—II: impact on nutrition and implications for food security and its costs,” Economic and Political Weekly (2013): 60-73.

[58] Randeep Kaur, “Estimating the impact of school feeding programs: Evidence from mid day meal scheme of India,” Economics of Education Review 84 (2021): 102171, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2021.102171

[59] Monica Jain, “India’s struggle against malnutrition—is the ICDS program the answer?,” World Development 67 (2015): 72-89, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2014.10.006

[60] Clément Imbert and John Papp, “Short-term migration, rural public works, and urban labour markets: Evidence from India,” Journal of the European Economic Association 18, no. 2 (2020): 927-963, https://doi.org/10.1093/jeea/jvz009

[61] Clement Imbert and John Papp, “Labor market effects of social programs: Evidence from India’s employment guarantee’” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 7(2) (2015): 233-263, https://doi.org/10.1257/app.20130401

[62] Sinha, “Hunger and food security,” 320 – 331.

[63] “Study points towards hunger and destitution amidst hope for a V-shaped economic recovery, Inclusive Media for Change, December 20, 2020, https://www.im4change.org/news-alerts-57/report-points-towards-hunger-and-destitution-amidst-hope-for-a-v-shaped-economic-recovery.html.

[64] National Consortium on MGNREGA, CORD and Azim Premji University, Employment Guarantee during Covid-19: Role of MGNREGA in the year after the 2020 lockdown (Bengaluru: Azim Premji University, 2022), https://azimpremjiuniversity.edu.in/faculty-research/employment-guarantee-during-covid-19-role-of-mgnrega-in-the-year-after-the-2020-lockdown

[65] Dipa Sinha, “Impact of COVID-19, Lockdowns and Economic Slowdown on Food and Nutrition Security in India,” in Reimagining Prosperity: Social and Economic Development in Post-COVID India, (Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore, 2023), 153-170.

[66] Jean Drèze and Reetika Khera, “Chart: The Sharp Decline in Total Expenditure on Social Security Schemes,” The Wire, February 1, 2023, https://thewire.in/rights/chart-decline-expenditure-social-security-schemes-budget-2023

[67] FAO et al., “The State of Food Security”

[68] UNESCO, UNDP, UNFPA, UNHCR, UNICEF, UNWomen, World Bank and ILO, Education 2030: Incheon Declaration and Framework for Action for the implementation of Sustainable Development Goal 4: Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all (Paris: UNESCO, 2016) https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000245656.

[69] World Bank, Global Water Security and Sanitation Partnership (GWSP) Annual Report 2022 (World Bank, 2022), https://www.wsp.org/sites/wsp/files/publications/eThekwiniAfricaSan.pdf.