Task Force 4 – Refuelling Growth: Clean Energy and Green Transitions

Abstract

The G20 governments face compounding crises or ‘polycrisis’ while delivering the green transition over several political cycles. The multilateral challenge can only be addressed by engaging the G20, allowing structural green solutions to be embedded into national development pathways. COVID-19 green recovery packages have helped the progress of the green transition, but structural green transition policies that deliver longer-term returns—for example, natural capital/nature-based solutions—have received limited attention and investment. Governments need the assurance of a coordinated multilateral response and favourable treatment from international financial institutions. Policy options include continuing the status quo, with structural green policies remaining uncoordinated across governments, treated on a case-by-case basis, thereby leading to underinvestment; coordination among G20 members to define and promote structural green transition policies, identify priority policy areas, create concessionary finance opportunities and drive national investment; and development of a multilateral framework for structural green transition policies, inspired by the lessons learnt from the G20’s Enhanced Structural Reform Agenda (ESRA) and Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI) and aligned with such approaches as the Bridgetown Initiative. We recommend that the G20 adopt a shared, ambitious agenda that allows structural green transition policies to act as enablers of other policy goals and be the ‘badge’ that facilitates flow of green investment to low-income countries.

1. The Challenge

At the global level, the green economic transition is at risk of becoming unstable and incoherent, even as it accelerates. An increasingly complex set of interlinked policy challenges – described by some commentators as ‘polycrisis’[1],[a] – is pushing governments on the back foot, preventing a proactive and structural response to the needs of the green transition. Solutions to the perennial challenges of risk, resilience and debt now need to be redefined as ‘green economy solutions’, but the task is impeded by compounding global risks.

This uncertain future is holding back sufficient green investment, most acutely in the Global South,[2] and deepening a policy coherence gap globally as governments move beyond COVID-19-linked green stimuli and green recovery frameworks.[b] Emerging economies risk dependence on carbon- and nature-intensive economic models, missing the window to leapfrog to green technologies through targeted funding. Meanwhile, governments in industrialised countries are stepping into the policy gap with unilateral and uncoordinated green industrial policy measures, driven by domestic and trade concerns.

Governments currently lack a comprehensive roadmap of: what a green structural transition looks like; which green policies (and measures) are, structurally, the most important ones; and which of these policies have the best evidential and investment case.

Hopkins and Greenfield have attempted to define and map green structural reform measures as green reforms that “aim to be systemic, long-lasting, and general purpose” and “set expectations and a clear sense of direction”.[3] Many green structural policies offer consistent and clear social returns – from natural capital investment (see Annex 2) to small-scale renewables to gender-just green job schemes – but they are being crowded out by trade-exposed sectors and measures.[4] Investment is flowing, but it is patchy, uncoordinated and insufficient, leaving many countries behind.

2. The G20’s Role

A G20 consensus on key structural green transition policies can serve as a multilateral tool to channel funds to nations currently outside of leading trade blocs or green sectors that are not subject to trade-competitive surges in funding. A central lesson of the 2008-2009 recession[5] is that policy certainty around a foundation of green structural measures is key to public investment to maximise returns, but especially to draw private investment.

However, governments will not raise their green economic ambition unless they have substantial social mandates. National and local ‘social contracts’ are starting to bring new economic, social and ecological priorities to the surface,[6] especially in rapidly growing and urbanising countries such as India. Involving citizens in policy and behaviour change – similar to the aim of India’s LiFE (Life for Environment)[7] – shows the importance of pro-planet governance for enabling national conditions for structural green transition.

Internationally, the G20 is the only group positioned to effectively shape structural reform agendas by putting a label next to policies that are on the critical path to sustainability, address systemic and financing risks for green transition, and push back policy incoherence. The Enhanced Structural Reform Agenda (ESRA), prior to the COVID-19 crisis, and the coordination of the Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI) emergency measures (see Annex 3) demonstrate the scope for G20 action. A window of opportunity is open as the Indian G20 presidency aspires to be a leader in “constructive and consensus-based solutions” to environmental challenges and “the premier global forum for cooperation on global economic and financial issues.”[8]

A multilateral signal is needed as it can provide confidence and assurance for all governments to invest both financial and political capital and persist in laying the foundation of the green transition in times of uncertain geopolitics.

3. Recommendations to the G20

We recommend that the G20 governments explore with urgency a means of communicating consensus on the breadth of the structural green transition policies that must be made viable at a global level, allowing high-impact structural policies with the greatest economic and environmental returns to be brought into the financial scope for all countries.

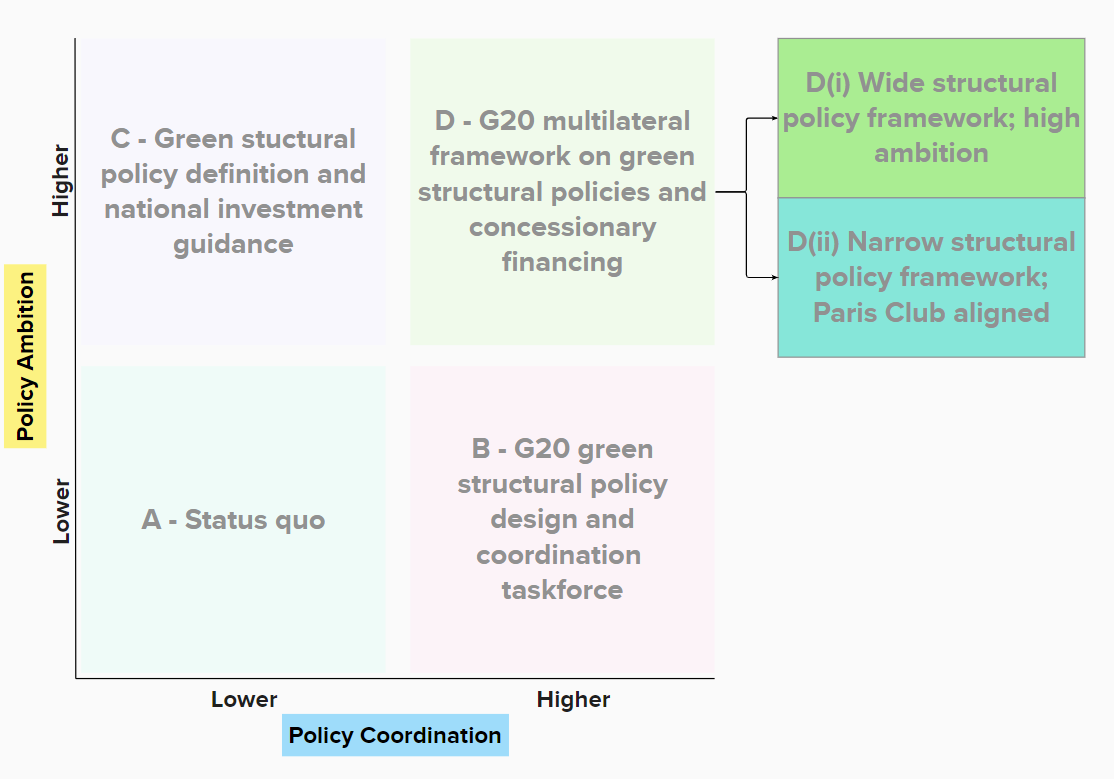

We see two complementary aspects of this aspirant multilateral framework – greater policy coordination (across and beyond the G20 governments) and deeper policy ambition to deliver the green economy transition. Figure 1 maps these as a 2×2 policy opportunity space:

Figure 1: An Opportunity Space for the G20 on Structural Green Transition Policies

Source: Authors’ own

In the following paragraphs, we describe the different options [A, B, C, D, D(i) and D(ii)] that are commensurate with the different levels of G20 multilateral coordination or policy ambition with regard to green structural measures. Each option aims to provide greater policy coherence and investment support and deeper political mandate for the kinds of foundational policies described in Annex 1.

Option A: Status Quo

The status quo of low ambition and coordination for essential green structural measures is not sustainable. The combination of trade competition and narrow action in the Global North and weak action in the Global South because of debt and finance barriers is driving a two-speed transition that adds up to less than the sum of its parts.[c]

Such a transition will be unstable and non-commensurate with achieving the Agenda 2030 goals for climate, nature and economic development. With developing economies locked out of the realistic prospects of ‘leapfrogging’ high-carbon development pathways, emerging calls for broad-based debt cancellation approaches to take a leading role in the transition will rightly gain traction;[9] the G20 governments should give these serious consideration.

Option B: G20 Green Structural Policy Design and Coordination Task Force

A G20-mandated design and coordination task force will be a process-focused route to fleshing out a multilateral response to green structural policy. Policy ambition will be potentially lower than that for other options since consensus and reaching shared positions will be the primary goal and ambition may be pulled towards the lowest common denominator.

In terms of implementation, the task force will focus on identifying priority green structural measures among the wider suite and building further consensus on actively accelerating deployment or removing barriers to implementation, including lack of access to grants and concessionary, private and guaranteed finance. Carbon pricing, green trade and border adjustment mechanisms are the key areas where frictions may be mitigated. Promising examples of green transition and case studies on deployment of structural measures can also be highlighted across G20 members.[10] The model envisioned will build on the elements of the G20/OECD ESRA and align with the Bridgetown Initiative (see Annex 3).

An important aspect will involve using a superstructure of shared intent on green structural transition to bear some of the weight of financing the transition. A G20 monitoring and reporting framework with internal task force milestones, connected with the G20 Bali Leaders’ Declaration (especially Point 16 on climate finance)[11] and the forward priorities of the forthcoming Brazil- and South Africa-hosted G20 summits, such as the Just Energy Transition Partnerships (JET-P) (see Annex 3), will also be effective.

Option C: Green Structural Policy Definition and National Investment Guidance

A policy ambition-focused route will create the conditions for flow of investment to clearly defined priority structural green transition policies. Hopkins and Greenfield[12] provide a starting point and a focus on systemic, long-lasting and general-purpose green transition policies and ‘The Green New Consensus’[13] identifies further crucial structural aspects. Guidance can focus on sequencing and direction-setting for future G20s.

An important commitment will involve creating a toolkit of evidence to help governments navigate, prioritise and implement structural policies, according to their own priorities. Patel and Steel provide evidence and guidance for nature and natural capital investment policies with significant return on investment (see Annex 2).[14] This route will focus on pushing the subset of structural transition policies suited to national-level adoption, with preferential finance access and reduced policy risk granted by G20 backing. National governments can club themselves together as implementation partners to pool expertise, co-finance and drive aligned implementation.

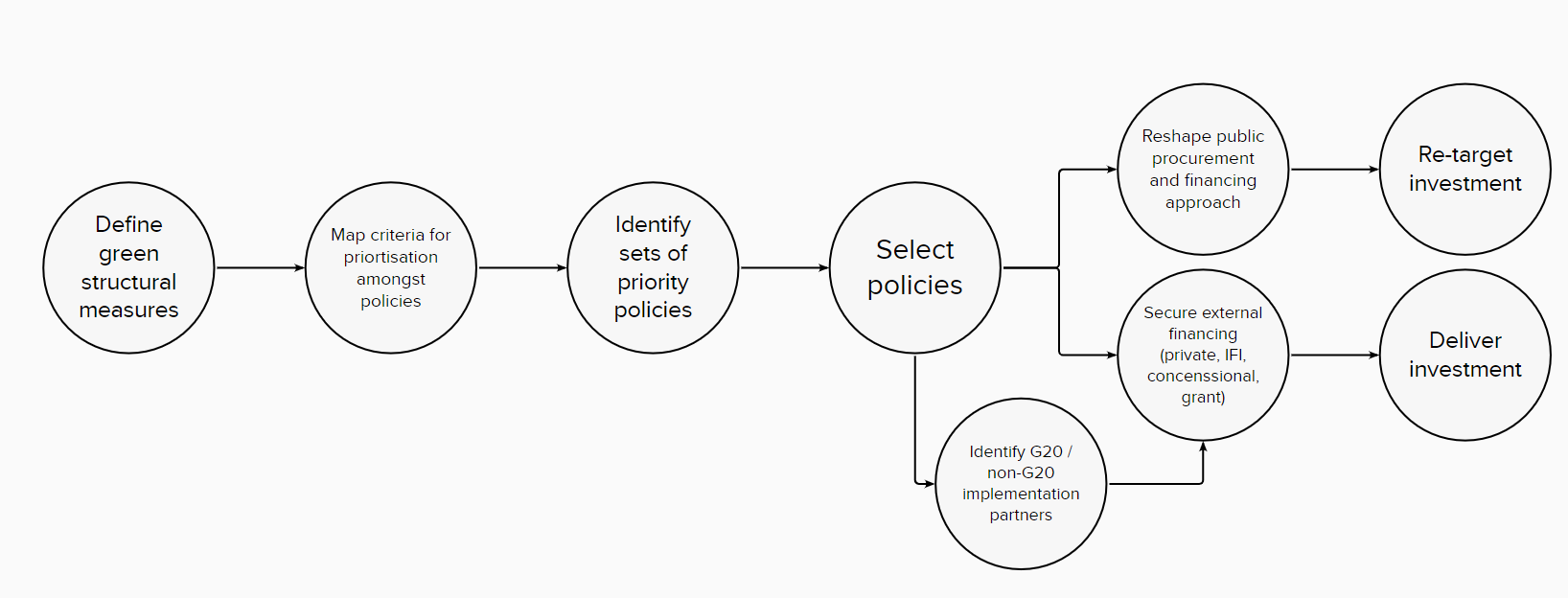

Figure 2: Green Structural Investment Flow Diagram

Source: Authors’ own

A non-partnered approach to structural transition measures can exacerbate trade-competitive green policies, leading to a combination of options B and C in option D, as discussed below.

Option D: G20 Multilateral Framework on Green Structural Policies and Concessionary Financing

This ambitious approach combines high policy ambition and coordination by creating a G20-mandated task force and common framework along the lines of ESRA. By jointly defining and clarifying key structural policies that are crucial to green transition, it will seek to bind governments, multilateral development banks (MDBs), international financial institutions (IFIs) and, ultimately, private creditors for greater financing and investment support.

The means of implementation will be recognition of key structural measures that promote global public goods (such as natural capital investment or fossil fuel subsidy reform), shared language on investment priorities to reduce policy risk or explicit credit guarantees, concessional funds or direct grants. Attention should be paid to the quality of funds.[15] A spectrum of frameworks is possible, ranging from a ‘wide’ framework that is ambitious in terms of the scope of the policies covered to a ‘narrow’ framework that focuses on a smaller set of key policies, and may be more appealing to creditors.

D(i): Wide Structural Policy Framework – High Ambition

In this high ambition framework, the G20 governments will endorse a mechanism for a more favourable treatment of the whole breadth of green structural policies (see Annex 1). This will be commensurate with the scale of the transition challenge and scientific and economic evidence[16] on the urgent need for sustained green investment. It will also lay down a marker on consensus-based governance and pro-planet solutions for the G20 – a corrective to green unilateralism.

The framework can align and build on the Bridgetown Initiative approach of using surplus special drawing rights (SDRs), held by advanced economies, to open untapped fiscal space for developing and indebted economies.[17] With their breadth and duration, priority green structural reforms must be national government-backed and can be the government-led complement to Just Energy Transition Partnership (JET-P) investment approaches, wherein the ambition is (in principle, at least) to ensure that new spending is not on government balance sheets, but involves creditor-project loans (see Annex 3). As this spending moves off government balance sheets, fiscal space is opened up for broad-based, high economic, social and environmental return on investment under the rubric of ‘green structural measures.’[d] The assurance of successful beginnings to JET-P-type programmes will provide a basis for further concessionary financing or set the foundation for debt-swap approaches, including those related to nature.[18]

By keeping the scope of structural measures wide and including those that have important social impact (such as gender-inclusive green job creation schemes), this framework will be best aligned with also creating the social conditions for effective green transition. The eco-friendly lifestyle and the eco-social contract,[e] envisioned by LiFE and the Agenda 2030, are central to a coherent transition.

D(ii): Narrow Structural Policy Framework – the Paris Club Aligned

A narrow framework is a cautious route for the G20 governments, building on the lessons of the DSSI and the G20 Common Framework for Debt Treatments (see Annex 3) and the reluctance of indebted governments to make full use of the facilities that put their credit rating at risk or had little private creditor participation.[f] All debt suspension and enhanced concessionary support proposals require substantial effort from the G20 governments to incentivise credit rating agency and private creditor engagement.

This framework will move towards ensuring a shared position on investing in green structural measures, secured by some buy-in from the Paris Club, credit rating agencies, key bilateral creditors and relevant IFIs/MDBs. The G20 can define a ‘top tier’ of green structural measures, wherein there is a consensus on a) being part of the critical path for green transition; b) offering medium-term fiscal returns (fiscal flows or direct costs avoided); and c) clear social return on investment. The most plausible candidate measures[19] include: green infrastructure investment; natural capital investment; and green skills and qualification measures.

The G20 governments can then work with the International Monetary Fund (IMF), IFIs and key bilateral creditors to establish stronger recognition of key green structural measures and appropriate carve-outs from debt payment and restructuring processes. This will be pursued in tandem with ensuring that the Paris Club considers such measures in scope for concessional treatment and parity with existing development and debt-for-nature swap[20] special provisions.[21]

This brand of multilateral framework is a fallback response to D(i) and should be considered less transformative for creating a political and financial vehicle to properly fund structural green transition policies. It will, nonetheless, represent an important step-up in G20 multilateral coordination around the green transition, an alternative to unilateral industrial policy.

Key G20 Recommendations

- Build a G20-backed multilateral framework for structural green transition policies that drives coherence and long-term investment towards key structural policy measures which remain acutely under-resourced – for example, investment in natural capital & nature-based solutions.

- Collaborate amongst G20 governments, IFIs, bilateral and private creditors to develop a pathway towards concessional green structural policy financing – with particular emphasis on countries in the global south, and heavily indebted countries.

- Create a G20 task force on structural green transition policies that can build coherence and consensus as governments beyond green stimulus and recovery packages. This includes reducing barriers to implementation, such as via sharing promising examples, case studies of long term deployment, and financing approaches.

- Develop a shared G20 definition of structural green transition policies and highest priority measures to build credibility for supporting and concessionary investment activities from governments, IFIs, MDBs and capital markets.

- Design a shared toolkit on structural green transition policies to help guide national investment strategies, and assist governments with prioritising amongst, and implementing structural policies that align with national priorities.

Annex 1

Illustrative green structural reform measures[22]

| High-level green structural reform measures | Specific green structural reform measures | ||

| 1 | Strengthened planning, strategies and governance | 1a | Integrated beyond-GDP metrics |

| 1b | Cross-ministry coordination | ||

| 1c | Multilateral cooperation (SDG17) | ||

| 2 | Green fiscal reform | 2a | Higher CO2 pricing |

| 2b | Fossil fuel subsidy reform | ||

| 2c | Fossil fuel funding moratorium | ||

| 3 | Green monetary tools | ||

| 4 | Sustainable financial system | 4a | Broadened corporate reporting |

| 5 | Just transition and inclusion policies | 5a | Just transition plans for sunset industries |

| 5b | Intersectional environmental policymaking | ||

| 6 | Green skills and qualification measures | ||

| 7 | Nature-based solutions | 7a | Natural capital investment |

| 8 | Green regulatory strengthening and deregulation | 8a | Mainstream green conditionality thresholds |

| 8b | Zero-carbon power and transport targets | ||

| 8c | Environmental non-regression commitments | ||

| 9 | Green infrastructure investment | 9a | Green innovation, R&D investment |

| 9b | Green energy investment | ||

| 9c | Green transport investment | ||

| 9d | Green buildings upgrades | ||

| 10 | Empower green behaviour change | 10a | Alignment with digitalisation policy agenda |

Source: Chris Hopkins, Oliver Greenfield. “Setting a structural agenda,” p5

Annex 2

Investment in nature, natural capital and nature-based solutions (NbS)

Investment in nature and key ecosystems is a structural policy with some of the highest returns in economic, environmental and social criteria.[23] Whether maintaining and restoring natural capital or using natural systems to cost-effectively deliver mitigation or adaptation through NbS, investment case in the G20 is strong – as shown by green recovery packages in India, France, Brazil and Uganda.[24] The economics of land degradation (ELD) methodology used in India’s Bundelkhand region between 2011 and 2018 show the further extension of this opportunity, with an estimated a 75- to 120-fold return on investment in nature.[25]

Annex 3

Summaries of ESRA[26],[27], DSSI[28],[29], JETP[30],[31] and the Bridgetown Initiative[32],[33]

Enhanced Structural Reform Agenda (ESRA)

Between 2016 and 2019, the OECD assisted in monitoring G20 nations’ progress on ‘structural reform priority areas’, including ‘promoting inclusive growth’, ‘promoting trade and investment openness’, and importantly ‘enhancing environmental sustainability’. Though the process was not mentioned in Bali G20 Declaration, a refreshed and relaunched version based on the common agenda for structural green transition policies is a key opportunity for G20 governments.

Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI)

The G20/IMF/World Bank DSSI offered partial suspension and deferral of debt-service payments to qualifying countries during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020-2021. The aligned ‘Common Framework for Debt Treatments’ offered broader support to the most debt-distressed countries, but struggled to meet its intended purpose with the only applicants – Chad, Ethiopia, and Zambia – choosing not to complete the process.

Just Energy Transition Partnerships (JET-P)

Just energy transition has emerged from climate COPs as a means of financing social processes to ease just transitions to lower-carbon economies, such as exiting coal-fired energy generation. South Africa has led the way with its just transition approach, with Indonesia following in 2022, and India, Vietnam, and Senegal as potential future candidates. There is tension regarding the mixed quality of funding provided as part of partnerships.

The Bridgetown Initiative

The Bridgetown Initiative is a transformative action plan to respond to polycrisis, put forward by Mia Mottley, Prime Minister of Barbados. It considers cost of living issues driven by the war in Ukraine and COVID-19, the wider developing world debt crisis from COVID-19 and disaster impact, and the ongoing climate crisis, as joint drivers for the need to provide emergency.

Attribution: Chris Hopkins and Gitika Goswami, “Fixing the Green Investment and Coherence Gap Through Structural Green Transition Policies,” T20 Policy Brief, June 2023.

The authors thank Saundharaya Khanna, Jean McLean and Ben Martin for their inputs.

Bibliography

Ahmed, Masood, Hannah Brown. “Fix the Common Framework for Debt Before It Is Too Late.” Center for Global Development Blog, January 18, 2022.

Barbados MFAFT. “The 2022 Bridgetown Initiative.” Barbados Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Foreign Trade, September 23, 2022.

Chaturvedi, Sachin. “G20 – A Primer.” Background Note Prepared for G20 University Connect, 2022, Accessed March 2023.

Development Alternatives. “Land Remediation for Achieving Global and National Targets: Case Study of Bundelkhand (India) through Capitals Approach.” Development Alternatives Policy Brief, May 13, 2020.

G20. “G20 BALI LEADERS’ DECLARATION Bali, Indonesia.” November 20, 2022.

German Environment Agency. “The Green New Consensus. Study Shows Broad Consensus on Green Recovery Programmes and Structural Reforms.” September 1, 2020.

Green Economy Coalition. “Green Economy Tracker: Green COVID-19 Recovery.” Accessed March 2023.

Hausman, Ricardo. “Dodgy Climate Finance.” Project Syndicate, March 30, 2023.

Hopkins, Chris, Oliver Greenfield. “Setting a structural agenda for a green economic recovery from COVID-19.” GEC/PIGE Discussion Paper. June 14, 2022.

Hujo, Katja. “A New Eco-Social Contract.” UNRISD Issue Brief, March 3, 2021.

Johnston, Robert. “Industrial Policy Nationalism: How Worried Should We Be?” Center on Global Energy Policy blog, February 7, 2023. Accessed March 2023

Kelly, Laura, Anna Ducros, Paul Steele. “Redesigning debt swaps for a more sustainable future.” IIED Issue Brief, April 21, 2023.

Kramer, Katherine. “Just Energy Transition Partnerships: An opportunity to leapfrog from coal to clean energy.” IISD Brief, December 7, 2022.

Lumbanraja, Alvin Ulido, Teuku Riefky, “International Financing Framework To Bridge The Climate Financing Gap Between Developed And Developing Countries.” T20 Indonesia Task Force 7, October 17 2022.

OECD. “The OECD Technical Report on Progress on Structural Reform under the G20 Enhanced Structural Reform Agenda (ESRA).” Accessed March 5, 2023.

Patel, Sejal, Paul Steele et al. “Post-COVID Economic Recovery and Natural Capital: Lessons from Brazil, France, India, and Uganda.” Green Economy Coalition, March 14, 2022.

Persaud, Avinash. “Breaking the Deadlock on Climate: The Bridgetown Initiative.” Groupe d’études géopolitiques. November 2022.

UN DESA. “The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2022.” July 7, 2022.

UNEP. “Building a Greener Recovery: Lessons from the Great Recession.” Barbier, E.B. United Nations Environment Programme. September 1, 2020.

UNEP. “The State of Finance for Nature in the G20.” UN Environment Report, January 2022.

Whiting, Kate, HyoJin Park. “This is why ‘polycrisis’ is a useful way of looking at the world right now.” World Economic Forum blog, March 7, 2023.

Woolfenden, Tess, Sindrs Sharma Khushal. “The debt and climate crises: Why climate justice must include debt justice.” Debt Justice Discussion Paper, October 27, 2022.

World Bank. “Brief: Debt Service Suspension Initiative.” March 10, 2022.

Endnotes

[a] In the polycrisis the shocks are disparate, but they interact so that the whole is even more overwhelming than the sum of the parts.

[b] See Green Economy Tracker.; and Green Recovery from the OECD.

[c] But successful north-south coordinating initiatives include International Solar Alliance and Coalition of Disaster Resilience Infrastructure (CDRI) (https://www.cdri.world/).

[d] An additional benefit would be in ‘green structural measures’ providing a structure and a justification for ensuring new financing stayed in-country for those highly indebted, mitigating worries it would bail out favoured private and bilateral creditors at the expense of multilateral institutions.

[e] See Katja Hujo (2021) and the Global Research and Action Network for a New Eco-Social-Contract:

[f] For details on criticism of DSSI implementation, see Bretton Woods Project:

[1] Kate Whiting, HyoJin Park, “This is why ‘polycrisis’ is a useful way of looking at the world right now”, World Economic Forum blog. March 2023.

[2] Alvin Ulido Lumbanraja, Teuku Riefky, “International Financing Framework To Bridge The Climate Financing Gap Between Developed And Developing Countries.” T20 TF7, Indonesia, October 2022.

[3] Chris Hopkins, Oliver Greenfield, “Setting a structural agenda for a green economic recovery from COVID-19.” GEC/PIGE Discussion Paper, June 2022.

[4] Chris Hopkins, Oliver Greenfield. “Setting a structural agenda,” p10

[5] UNEP, “Building a Greener Recovery: Lessons from the Great Recession.” Ed Barbier. United Nations Environment Programme, Geneva, September 2020.

[6] Katja Hujo, “A New Eco-Social Contract.” UNRISD Issue Brief, March 2021.

[7] Sachin Chaturvedi, G20. “G20- A Primer.” Background Note Prepared for G20 University Connect, accessed March 2023.

[8] Sachin Chaturvedi, G20. “G20- A Primer,” (2022) p1-3

[9] Tess Woolfenden, Sindra Sharma Khushal, “The debt and climate crises: Why climate justice must include debt justice.” Debt Justice Discussion Paper, October 2022.

[10] Chris Hopkins, Oliver Greenfield. “Setting a structural agenda,” p33-41

[11] Bali G20 Declaration. “G20 BALI LEADERS’ DECLARATION Bali, Indonesia, 15-16 November 2022.” p6.

[12] Chris Hopkins, Oliver Greenfield. “Setting a structural agenda,” p14

[13] German Environment Agency. “The Green New Consensus. Study Shows Broad Consensus on Green Recovery Programmes and Structural Reforms.” September 1, 2020.

[14] Sejaj Patel, Paul Steele et al, “Post-COVID Economic Recovery and Natural Capital: Lessons from Brazil, France, India, and Uganda.” Green Economy Coalition, March 2022.

[15] Ricardo Hausman, “Dodgy Climate Finance.” Project Syndicate Commentary, March 17 2023.

[16] UNEP, “Building a Greener Recovery,” 2020.

[17] Avinash Persaud, “Breaking the Deadlock on Climate: The Bridgetown Initiative.” Geopolitique, November 2022.

[18] Laura Kelly, Anna Ducros, Paul Steele. “Redesigning debt swaps for a more sustainable future.” IIED Issue Brief, April 21, 2023.

[19] Chris Hopkins, Oliver Greenfield. “Setting a structural agenda,” p17-20

[20] Laura Kelly, Anna Ducros, Paul Steele. “Redesigning debt swaps,” 2023.

[21] Paris Club, “Debt swap provisions.” Accessed March 2023.

[22] Chris Hopkins, Oliver Greenfield. “Setting a structural agenda,” p5

[23] UNEP, “The State of Finance for Nature in the G20.” UN Environment Report, January 2022.

[24] GEC, “Post-COVID Economic Recovery and Natural Capital,” March 2022

[25] Development Alternatives, “Land Remediation for Achieving Global and National Targets: Case Study of Bundelkhand (India) through Capitals Approach.” Development Alternatives Policy Brief, May 2020.

[26] OECD, “The OECD Technical Report on Progress on Structural Reform under the G20 Enhanced Structural Reform Agenda (ESRA).”Webpage, accessed March 2023.

[27] G20. “G20 BALI LEADERS’ DECLARATION,” 15-16 November 2022

[28] World Bank, “Debt Service Suspension Initiative.” February 2022.

[29] Tess Woolfenden, Sindra Sharma Khushal, “The debt and climate crises,” (2022) p5

[30] Avinash Persaud, “Breaking the Deadlock on Climate,” (2022)

[31] Ricardo Hausman, “Dodgy Climate Finance.” (March 2023)

[32] Barbados MFAFT, “The 2022 Bridgetown Initiative.” Barbados Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Foreign Trade. (September 2022). Accessed March 2023.

[33] Avinash Persaud, “Breaking the Deadlock on Climate,” (November 2022).