Task Force 4. Refuelling Growth: Clean Energy and Green Transitions

The G20 committed in 2009 to phase out and rationalise fossil fuel subsidies in the medium-term. Yet subsidies exceeded US$1 trillion globally for the first time in 2022, following the global energy price crisis. Reforming public support for fossil fuels is crucial to level the playing field for renewable energy and create sustainable energy systems that will protect consumers from volatile fossil fuel prices. This frees up funds for other domestic priorities and climate mitigation and adaptation efforts. Well-planned reform can also support energy access for the poor and improve the quality of energy systems. How can the G20 reinvigorate momentum and drive the full implementation of subsidy reform commitments? This Policy Brief discusses the challenges and opportunities for advancing progress on fossil fuel subsidy reform, including specific challenges in the Global South. It draws on lessons from G20 members with high poverty rates and massive energy access needs.

1. The Challenge

In 2009, G20 members committed to fossil fuel subsidy reform, stating they would “phase out and rationalise over the medium-term inefficient fossil fuel subsidies while providing targeted support for the poorest;”[1] since then, the grouping has reiterated the same commitment every year. Reflecting the G20’s global influence, similar language was adopted by almost all countries in 2015 under the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 12.c.1, and in the Paris Agreement under Article 2.1 to align financial flows with reducing greenhouse gas emissions. More recently, there were commitments to the “phase-out of inefficient fossil fuel subsidies, while providing targeted support to the poorest,”[2] in the cover decisions from the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) Conference of the Parties (COP) 26 and 27, and commitments to reform subsidies that negatively affect biodiversity in the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) in 2022.[3]

Government support—or “public financial flows”—for energy is important because it influences the movement of much larger private investment flows. It includes subsidies and other forms of support, like investments by state-owned enterprises (SOEs) and lending by public financial institutions. Shifting support away from fossil fuels and toward clean energy sends a strong market signal to drive investment in low-carbon technologies and markets. It can also protect public institutions from becoming ‘lenders of last resort’ for fossil assets and over-exposure to risks of asset stranding.

Climate models show that the world needs drastic emissions cuts to get on-track with Paris Agreement goals and keep alive the hopes of limiting global warming to 1.5°C.[4] Urgently needed are commitments to end all new fossil fuel investments and a managed decline of fossil fuel production and consumption. Rapidly phasing out public support for fossil fuels is a critical pillar in any concrete plan to reduce global production and consumption of coal, oil, and gas.

1.1 Despite Commitments—Subsidies are Increasing and Undermining Clean Energy

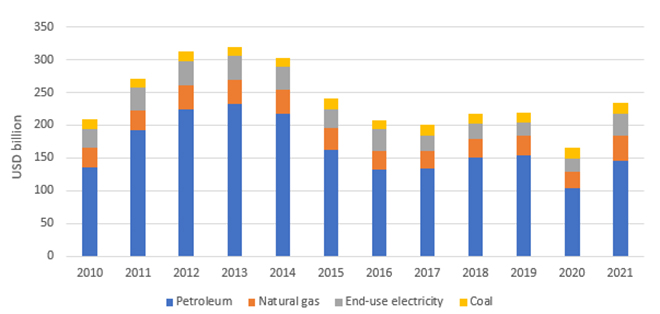

In 2021, G20 countries together provided US$190 billion in fossil fuel subsidies, up from US$147 billion in 2020.[5] The trend was driven by rising oil and gas prices, increased support to consumers during winter in Europe due to the Russian invasion of Ukraine, and tax exemptions for some fossil-fuel-based SOEs.

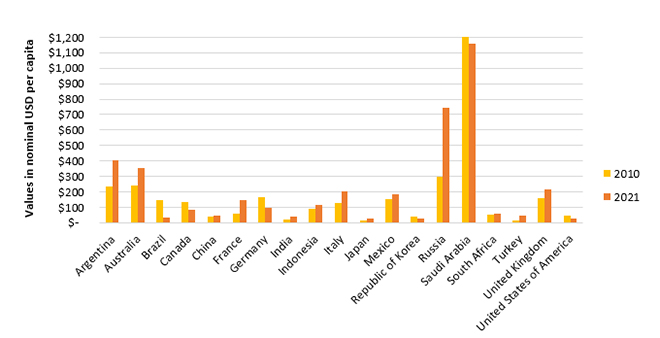

Figure 1 illustrates the lack of progress on fossil fuel subsidies in absolute terms following the G20 agreement in 2009. Figure 2 breaks this down by country, on a per capita basis, showing that subsidies have increased in 13 out of 19 tracked jurisdictions. Globally, the most recent estimates from the IEA suggest that fossil fuel consumption subsidies alone exceeded US$1 trillion in 2022.[6] Apart from consumption subsidies, G20 governments are also offering subsidies to cut costs for fossil fuel producers. Some examples of producer subsidies include tax breaks, public finance allocated specifically for fossil fuel production, and subsidies to SoEs.

Figure 1: G20 Fossil Fuel Subsidies, 2010-2021

Source: Laan et al. 2023[7]

Figure 2: G20 Fossil Fuel Subsidies Per Capita, 2010 and 2021

Source: IISD and OECD 2022[9]

1.2 Social Impacts Remain a Stumbling Block for Reform—But Subsidies Often Fail to Meet Social Welfare Objectives

In many emerging countries, fossil fuel subsidies have been associated with supporting affordable access to energy. In the past year, the global energy price crisis has made this more widespread, with a number of economies introducing subsidies to improve consumer affordability. There is longstanding consensus, however, that support for fossil energy frequently does not benefit the most vulnerable populations in an efficient way.[10]

A 2015 review of fuel subsidies in 32 countries found that on average, the top 20 percent of households receive at least six times more benefits than the bottom 20 percent—the richer a household, the more energy it can afford to buy, and the more subsidy benefits it receives. Gasoline subsidies were found to be particularly regressive, with over 80 percent of the total subsidy benefits going on average to households in the top 40 percent of the population.[11] A 2020 survey of residential electricity subsidies in 2019, in the state of Jharkhand in India found around 60 percent of the benefits went to the richest 40 percent of households.[12]

The energy crisis caused by the Russian invasion of Ukraine may seem like a one-off crisis, but widespread efforts to introduce carbon pricing would imply at least a transitional period of high fossil energy prices. As a result, it is clear that countries require social protection systems that can more efficiently transfer benefits to vulnerable groups. The implementation of nationally appropriate social protection systems is required under SDG 1, and fundamental to being able to simultaneously achieve targets on affordable energy access for all (SDG 7) and fossil fuel subsidy reform (SDG 12).

2. The G20’s Role

Since 2009, the G20 has led on fossil-fuel subsidy reform commitments, paving the way for similar accords between many countries in different international forums.[13] Given the global implementation gap, in 2023 the G20 has an important leadership role to play: to push forward reform implementation, demonstrating globally that such commitments can and should be followed by firm action.

India, current G20 president, has a strong track record on reform implementation: it reduced the value of fossil fuel subsidies by 76 percent between FY2014 and FY2022.[14] Accelerated action on government support for fossil energy would also be well aligned with India’s call at COP27 for all fossil fuels to be phased down, which is being endorsed by others, including the EU.[15]

2.1 Overcoming Implementation Challenges: Lessons from the Global South

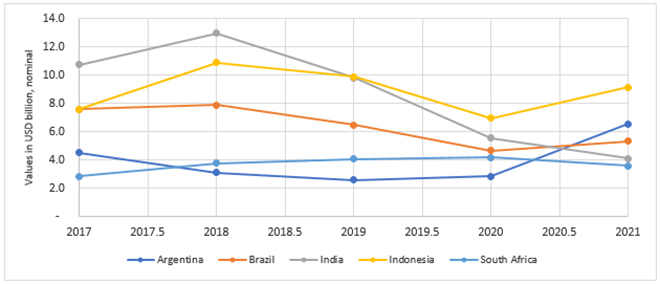

G20 countries from the Global South have arguably faced the biggest challenges implementing their reform, due to massive energy access needs and higher rates of poverty. A spotlight on their experiences, however, also demonstrates how challenges can be overcome. This brief highlights three critical areas to make progress on reform by drawing out common challenges from five G20 countries: Argentina, Brazil, Indonesia, India, and South Africa.

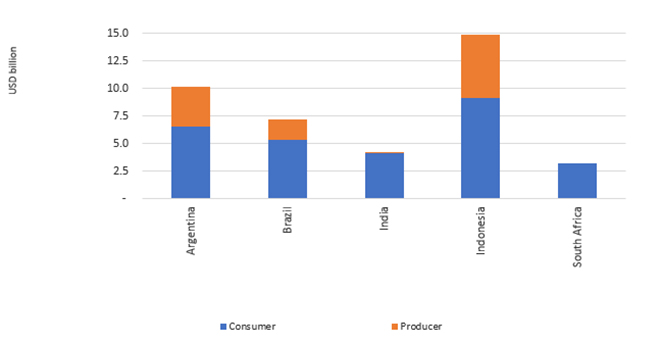

- Shifting fossil fuel subsidy savings to social protection and clean energy

Emerging economy G20 members have large consumer subsidies, reflecting the growing energy demands of their populations. Argentina, Brazil, Indonesia, India and South Africa all have high consumer subsidies (see Figure 3). However, universal energy subsidies are often inefficient in targeting poor beneficiaries.[16] Several attempts to reform these subsidies over the past decade demonstrate the potential to redistribute funds to poor beneficiaries to offset rising energy prices and otherwise invest in clean energy.

Indonesia’s experiences in 2014, for example, are notable on social protection—gasoline and diesel subsidy reforms enabled a budget revision that injected an extra US$10.1 billion into Ministry budgets.[17] India, meanwhile, has undertaken efforts to reduce expenditure linked to subsidies for liquefied petroleum gas (LPG). For its part, Brazil began targeting LPG subsidies to poor households, following the COVID-19 pandemic, through its income transfer program, Brasil Aid (“Auxílio Brasil”).[18] Argentina planned to introduce a gradual phase-in of energy subsidy reforms by cutting subsidies for the wealthiest and protecting low-income beneficiaries;[19] however, producers subsidies in the country continue to be promoted, in part encouraged by international financial institutions.

On clean energy, few countries have implemented reforms with an explicit and specific transfer of funds from a fossil support policy to a clean alternative, but India has shown strong leadership in an overall “greening” of its support measures. From FY2014 to 2022, while fossil fuel subsidies fell by 76 percent, subsidies for renewables increased by 250 percent and for electric vehicles, from nearly zero to more than US$0.3 billion.[20] There is still progress to be made—fossil fuel subsidies remain four times larger than clean energy subsidies[21]—but India’s experiences demonstrate that this type of shift is possible, and can be made more ambitious with targets and tracking trends.

To date, G20 statements on subsidy reform have committed to “phase-out and rationalize, over the medium term, inefficient fossil fuel subsidies that encourage wasteful consumption […] while providing targeted support for the poorest and the most vulnerable.”[22] The term “inefficient” is not defined and implies that some subsidies may be “efficient” and therefore not in need of reform. Such ambiguity is a challenge for accountability on implementation and should be avoided.

Based on these positive experiences with shifting support, G20 members can reposition their commitment, such that fossil fuel subsidies should be fully replaced by targeted non-energy-subsidy support for the poor and vulnerable. The G20 can further commit to shifting public financial flows away from fossil fuels and towards clean energy. This is better aligned with the Paris Agreement. It was recommended in the Think Tank 20 communiqué from the 2022 G20 summit,[23] but has yet to be reflected in any G20 commitments so far.

Figure 3. Fossil Fuel Subsidies in Argentina, Brazil, India, Indonesia and South Africa (2021)

Source: Authors’ own, using data from the fossil fuel subsidy track[24]

Source: Authors’ own, using data from the fossil fuel subsidy tracker[25]

Note: The tracker does not cover producer subsidies for South Africa

- Widening commitments to account for all public financial support for energy

As committed under the Paris Agreement, governments need to shift all public financial flows away from fossil fuels. This includes subsidies, investments by SOEs, and international and domestic public finance.

Most G20 emerging economies have large energy SOEs, which annually invest billions in new fossil energy infrastructure, and some of which receive billions in government support. There is generally a lack of transparency on these financial flows. In Argentina, for example, SOEs annually invested an average of US$27 billion between 2017-2019 in oil and gas production, not including US$2 billion in subsidies for the gas sector that alone exceeded the royalties received.[26] Between 2017-2019, SOEs in Brazil continued to introduce tax cuts for non-state companies to boost oil and gas production.[27] Indian energy SoEs are decreasing their investments in fossil fuels—in 2021 there was a decline of 14 percent in investments compared to 2020 by India’s 14 largest energy SoEs—and significant commitments to clean energy, such as NTPC Ltd’s target of 60 GW of renewable energy capacity by 2030.[28] In Indonesia, SOEs increased their average fossil investments over 2017-2019 to boost oil and gas production,[29] and during the pandemic, the government released large bailouts for these SOEs.[30] South Africa has a lack of transparency on government support to energy SOEs, providing bailouts for its troubled electricity SOE, Eskom, and funding the exploration and production of coal.[31]

Energy SOEs in G20 countries play a critical role in the energy transition and simultaneously bring in millions in government revenue, supporting jobs and local communities. However, there is currently no explicit G20 recognition of SOE investments as a major category of government support that needs to see a shift in financial flows, alongside subsidies, such that these state firms can deliver a share of clean energy targets and reduce the risks from their fossil-dependent business models. Broadening commitments to account for state firms would be a positive first step in better accounting for all public financial flows (see Recommendation 2).

- Transparency and timelines

A crucial challenge in implementing fossil fuel subsidy reform is the lack of transparency. In principle, SDG 12.c.1 requires governments to report on energy subsidies but as of late 2022, only 22 countries had completed the formal questionnaire on subsidy reporting. Of those, only five provided data, six claimed to have no subsidies, five said they were unable to provide data; and five asked for more time to respond.[32]

Indeed, most G20 governments are not highly transparent about fossil fuel subsidies.[33] Among emerging economies of the G20, both Argentina and India have good, transparent data for fossil fuel subsidies; Brazil, Indonesia and South Africa are more opaque. It is crucial that G20 members publicly disclose and provide detailed information on all fossil fuel subsidies, aggregating data together under reporting for SDG 12.c.1. (see Recommendation 3).

Adopting a timeline is also critical for accountability and tracking progress. Unlike the G7, who have committed to a 2025 timeline to phase-out fossil fuel subsidies, the G20 Leaders’ Declaration reaffirms the pledge to phase out fossil fuels every year but does not state a timeline[34] (see Recommendation 4). In order to demonstrate leadership at a global level, the G20 should be articulating its own timeline, in advance of the 2030 date already agreed upon by all UN member countries through SDG 12.

3. Recommendations to the G20

The world needs to see the G20 show leadership in urgently implementing a shift in public financial flows away from fossil fuels and towards clean energy, as agreed in Paris Agreement Article 2.c.1, under the UNFCCC, and SDG 12.

Building on lessons from G20 members from the Global South, where reforms are often seen to be most difficult, G20 governments should strengthen their commitment on fossil fuel subsidies, as follows:

- Redirect fossil fuel subsidy savings to social protection and clean energy: G20 members should shift a share of savings from reform into improved social protection and increased public support for clean energy, reflecting the need for better non-subsidy mechanisms to support populations during energy- and living-price crises, and the urgent need to crowd-in private investment for a rapid and socially responsible build-out of clean energy capacity by 2030.

- Account for all public financial support for fossil fuels. The G20 should broaden their commitment on subsidies to more explicitly include all public support for fossil fuels, including state-owned enterprise investment and lending by public financial institutions. They should mandate state-owned institutions to establish strategies for contributing to net-zero targets, including shifting financial flows.

- Improve transparency: G20 members should commit to annually report on all support for fossil fuels under indicator SDG 12.c.1, in a comprehensive manner and on an annual basis, thereby leading by example and encouraging improved data transparency from all parties to the SDGs.

- Set a timeline for reform: G20 members should adopt a specific timeline for fossil-fuel subsidy reform, bearing in mind the G7 goal to phase out fossil fuel subsidies by 2025, and the need to show leadership by fully implementing reforms before 2030, the date agreed upon by all UN member countries under SDG 12.

Attribution: Shruti Sharma et al., “Financing a Fair Energy Transition through Fossil Fuel Subsidy Reform,” T20 Policy Brief, July 2023.

[1] “Leaders’ Statement, The Pittsburgh Summit, September 24-25 2009,” US Department of the Treasury, last modified 2009.

[2] “Sharm El-Sheikh Implementation Plan,” UNFCCC, accessed June 23, 2023, https://unfccc.int/documents/624444.

[3] “COP15 ends with landmark biodiversity agreement”, UNEP, last modified 2022.

[4] IPCC, Summary for Policymakers. In: Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report, (Geneva: IPCC, 2023), https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/syr/downloads/report/IPCC_AR6_SYR_SPM.pdf.

[5] Climate Transparency, G20 Response to the Energy Crisis: Critical for 1.5°C, (Berlin: Climate Transparency, 2022); OECD and IEA, Support for Fossil Fuels Almost Doubled in 2021, Slowing Progress Toward International Climate Goals (Paris: OECD, and IEA, 2022), https://climate-transparency.app.box.com/s/z9grpfcybnagr4661458g2iu68giab69/file/1045001458599.

[6] IEA, Fossil Fuels Consumption Subsidies 2022, (Paris: IEA, 2022), https://www.iea.org/reports/fossil-fuels-consumption-subsidies-2022.

[7] Tara Laan, Anna Geddes, Deepak Sharma, Olivier Bois von Kursk, Livi Gerbase, & O’Manique, G20 Scorecard, (Geneva: IISD, 2023).

[8] Olivier Bois von Kursk, Greg Muttitt, Angela Picciariello, Lucile Dufour, Thijs Van de Graaf, Andreas Goldthau, and Diala Hawila, Navigating Energy Transitions: Mapping the Road to 1.5°C (Winnipeg: IISD, 2022), https://www.iisd.org/publications/report/navigating-energy-transitions.Last accessed 23 June 2023.

[9] IISD and OECD, Fossil Fuel Subsidy Tracker (Paris: OECD, and IISD, 2022), https://fossilfuelsubsidytracker.org/.

[10] Anna Zinecker, Lourdes Sanchez, Shruti Sharma, Chris Beaton, and Laura Merrill, “Getting on Target: Accelerating Energy Access through Fossil Fuel Subsidy Reform (Winnipeg: International Institute for Sustainable Development, 2018), https://www.iisd.org/system/files/publications/getting-target-accelerating-energy-access.pdf.

[11] D. Coady, V. Flamini, and L. Sears, The Unequal Benefits of Fuel Subsidies Revisited: Evidence for Developing Countries (International Monetary Fund, 2015), http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2015/wp15250.pdf.

[12] Shruti Sharma, Tom Moerenhout, and Michaël Aklin, How to Target Residential Electricity Subsidies in India: Step 2. Evaluating Policy Options in the State of Jharkhand (Winnipeg: IISD, 2020), https://www.iisd.org/publications/target-residential-electricity-subsidies-india-step-2.

[13] Indira Urazova, Susanne Flinner, Christopher Beaton, and Ivetta Gerasimchuk, Shifting Public Financial Flows From Fossil Fuels to Clean Energy Under the Paris Agreement (Winnipeg: International Institute for Sustainable Development, 2023) https://www.iisd.org/publications/report/global-stocktake-shifting-public-financial-flows.

[14] Swasti Raizada, Tara Laan, Medha Manish, and Balasubramanian Viswanathan, “Mapping India’s Energy Policy 2022: December 2022 Update,” International Institute for Sustainable Development, December 2022, https://www.iisd.org/story/mapping-india-energy-policy-2022-update.

[15] “Outcome of Proceedings,” Council of the European Union, last modified March 9 2023, https://www.consilium.europa.eu/media/62942/st07248-en23.pdf. Last accessed 23 June 2023.

[16] D. Coady , V. Flamini, and L. Sears, The Unequal Benefits of Fuel Subsidies Revisited: Evidence for Developing Countries (International Monetary Fund, 2015), http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2015/wp15250.pdf

[17] Rimawan Pradiptyo, Akbar Susamto, Abraham Wirotomo, Alvin Adisasmita, and Chris Beaton, Financing Development with Fossil Fuel Subsidies (Winnipeg: IISD, 2016), https://www.iisd.org/library/financing-development-fossil-fuel-subsidies-reallocation-indonesias-gasoline-and-diesel.

[18] “Presidente Jair Bolsonaro Sanciona Projeto de Lei Que Abre Crédito Para o Pagamento Do Auxílio Gás.” Planalto, last modified October 31, 2022, https://www.gov.br/planalto/pt-br/acompanhe-o-planalto/noticias/2021/12/presidente-jair-bolsonaro-sanciona-projeto-de-lei-que-abre-credito-para-o-pagamento-do-auxilio-gas.

[19] “Subsidies Slashed – Sharp Rises Coming for More than Four Million Households,” Buenos Aires Times, last modified August 17, 2022, https://www.batimes.com.ar/news/economy/subsidies-slashed-sharp-rises-coming-for-more-than-four-million-households.phtml.

[20] Raizada et al., “Mapping India’s Energy Policy 2022: December 2022 Update.”

[21] Raizada et al., “Mapping India’s Energy Policy 2022: December 2022 Update.”

[22] “G20 Bali Leaders’ Declaration,” The White House, last modified November 16, 2022, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2022/11/16/g20-bali-leaders-declaration/.

[23] “T20 Communiqué,” T20 Indonesia, accessed June 23, 2023, https://summit.t20indonesia.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/T20-Communique%CC%81.pdf.

[24] “Fossil Fuel Subsidy Tracker,” OECD, and IISD, accessed June 23, 2023, https://fossilfuelsubsidytracker.org/.

[25] IISD, and OECD, Fossil Fuel Subsidy Tracker, (Paris: OECD, and IISD, 2022), Last accessed 23 June 2023. https://fossilfuelsubsidytracker.org/.

[26] Angela Picciariello, “G20 Scorecard of Fossil Fuel Funding: Non-OECD Member Country Argentina,” IISD, ODI & OCI, 2022, https://www.iisd.org/system/files/2020-11/g20-scorecard-argentina.pdf.

[27] Bronwen Tucker, “G20 Scorecard of Fossil Fuel Funding: Non-OECD Member Country Brazil,” IISD, ODI & OCI, 2020, https://www.iisd.org/system/files/2020-11/g20-scorecard-brazil.pdf.

[28] Prateek Aggarwal, Siddharth Goel, Tara Laan, Tarun Mehta, Aditya Pant, Swasti Raizada, Balasubramanian Viswanathan, Anjali Viswamohanan, Christopher Beaton, and Karthik Ganesan, Mapping India’s Energy Policy 2022, (Winnipeg: IISD; New Delhi: CEEW, 2022), https://www.iisd.org/publications/mapping-india-energy-policy-2022.

[29] Anissa Suharsono, “G20 Scorecard of Fossil Fuel Funding: Non-OECD Member Country Indonesia,” IISD, ODI & OCI, 2020, https://www.iisd.org/system/files/2020-11/g20-scorecard-indonesia.pdf.

[30] Anissa Suharsono, Murtiani Hendriwardani, Theresia Betty Sumarno, Jonas Kuehl, Martha Maulidia, and Lourdes Sanchez, Indonesia’s Energy Support Measures: An Inventory of Incentives Impacting the Energy Transition (Winnipeg: IISD, 2022).

[31] Anna Geddes, “G20 Scorecard of Fossil Fuel Funding: South Africa,” IISD, 2020, https://www.iisd.org/system/files/2020-11/g20-scorecard-south-africa.pdf.

[32] Indira Urazova, Susanne Flinner, Christopher Beaton, and Ivetta Gerasimchuk, Shifting Public Financial Flows from Fossil Fuels to Clean Energy Under the Paris Agreement (Winnipeg: International Institute for Sustainable Development, 2023) https://www.iisd.org/publications/report/global-stocktake-shifting-public-financial-flows.

[33] Anna Geddes, Ivetta Gerasimchuk, Balasubramanian Viswanathan, Anissa Suharsano, Vanessa Corkal, Mostafa, Roth, Joachim et al., Doubling Back and Doubling Down: G20 Scorecard on Fossil Fuel Funding (Winnipeg: International Institute for Sustainable Development, 2023), https://www.iisd.org/publications/g20-scorecard.

[34] Van Der Burg, Laurie, and Shelagh Whitley, Fossil Fuel Subsidy Reform: From Rhetoric to Reality (Washington DC: ODI, 2015).