Task Force 1: Macroeconomics, Trade, and Livelihoods: Policy Coherence and International Coordination

Abstract

Global value chains (GVCs) refer to cross-border production networks where different stages of production occur across various countries.[1] Amid rapid globalisation, GVCs have now emerged as the dominant component of international trade in services and commodities, accounting for around 70 percent of overall international trade.[2] GVCs are now the focal point of international trade and production, offering developing countries a bankable opportunity to enhance economic output by participating in the global economy.[3]

Apart from the obvious benefit of access to a larger global market, participating in GVCs also enables developing countries to increase productivity, diversify exports,[4] generate high-value employment,[5] and enhance their trade balance. These direct benefits lead to several indirect benefits to the economy—most notably, increase in wage levels[6] leads to an rise in purchasing power of households, which in turn increases the demand for goods and services across various sectors, resulting in a strong multiplier effect in the economy.

While the benefits of participating in GVCs are well established, several challenges remain in ensuring equitable participation in these systems.

GVCs are intrinsically focused on specialisations. Given that different stages of production are modularised and spread across various countries, each country will need to achieve high levels of productivity to remain competitive in its module. If a country fails to remain competitive, it can easily be replaced by other countries attempting to expand their footprint. For example, in the case of the shoe manufacturing industry, major manufacturers in the sector have gradually shifted their production capacity away from China to Vietnam.[7] A key component was the lower labour costs in the Southeast Asian economies (the hourly labour cost in China is US$6.5 as compared to US$2.99 in Vietnam).[8]

Given the strong need to remain competitive, large firms that can ensure higher levels of labour productivity and are equipped with sound technological capabilities have a competitive advantage in GVC participation.[9] Micro, small, and medium enterprises are therefore marginalised from effective GVC participation, while multinational corporations have the edge.

The Challenges

There are several key factors that make MSMEs less competitive in comparison to large corporations:

Poor technological capability

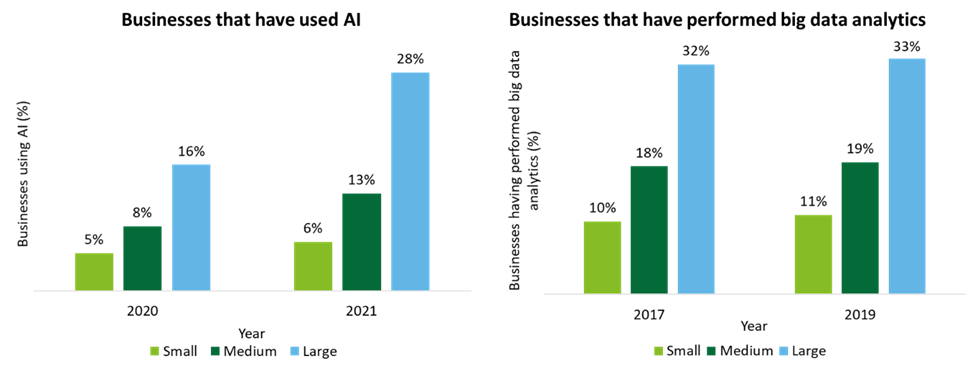

With the advent of Industry 4.0, new innovations have emerged in production technologies. Specifically, innovations such as robotic automation, 3-D printing, and automated quality control have substantially increased the competitiveness of producers. MSMEs, specifically those in developing nations, are under threat due to this changing technological landscape.[10] Even among developed nations, the adoption of Industry 4.0 concepts such as artificial intelligence (AI) and big data analytics is limited among MSMEs (see Figure 1).[a]

Figure 1: Percentage of businesses using AI and Big Data within OECD countries

Source: Authors’ calculation (simple average across nations) using OECD ICT Access and Use by Business dataset.[11]

Poor digital infrastructure

Effective supply chain management is key to the smooth functioning of GVCs. It ensures the agile movement of components and products across borders in the most cost-efficient manner. With increasing costs of storage and warehousing, several industries have adopted ‘just-in-time’ supply chain designs, which substantially reduce the need for warehousing. However, these supply chains require robust logistics connectivity and advanced interoperable digital solutions for real-time optimisation based on evolving circumstances. Thus, MSMEs seeking to be successful and competitive in GVCs will require advanced supply chain management systems and logistics infrastructure, which they often lack. For example, among Organisation of Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) nations, the uptake for digital supply chain management solutions stands at 40 per cent for large businesses, while that for small businesses is only 13 percent.[b] This significant gap in digitisation proves to be a major impediment to MSME participation in GVCs.[12] Further, MSMEs, specifically in least developed countries (LDCs) suffer an additional impediment due to the lack of digital trade facilitation platforms. Developed economies have a cross-border paperless trade implementation score of 57.59 percent, while LDCs score 24.44 percent, as per the United Nations Survey on Digital and Sustainable Trade Facilitation.[13] The lack of interoperable trade facilitation platforms leads to delays and congestions at the border, further delaying timelines.

Insufficient awareness of GVCs and lack of managerial talent

GVCs are being rapidly transformed by the increasing digitisation of the economy, which requires specialised talent—both technical and managerial. All aspects of GVCs, from the production of goods to their last-mile distribution, are being revolutionised by the introduction of digital technologies such as web-based platforms, Internet of Things (IoT), and AI. However, awareness among MSMEs on how to remain competitive in the digital economy is limited,[14] partly due to the lack of specialised managerial talent.

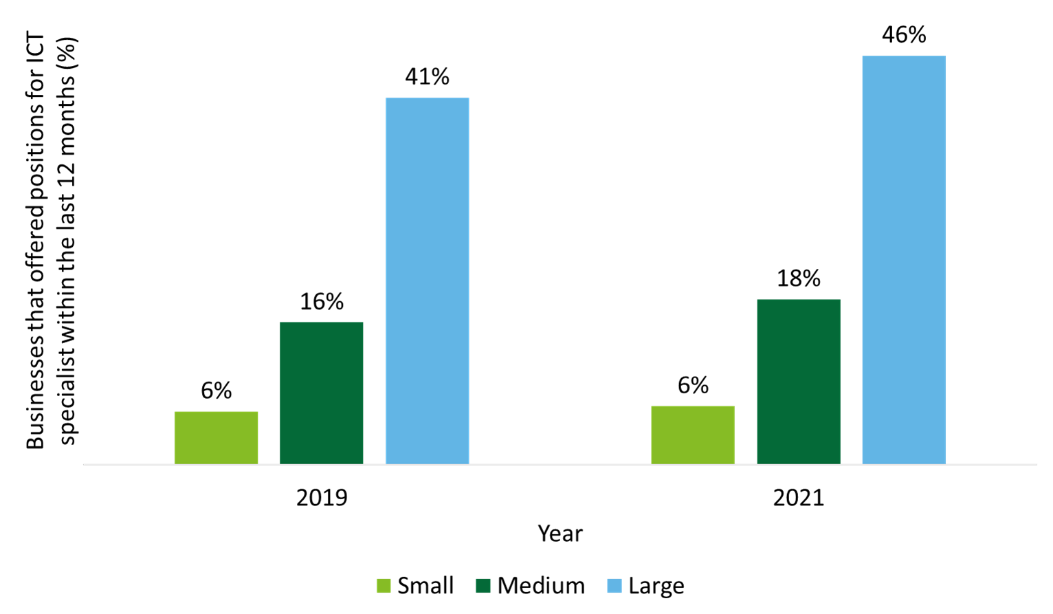

As can be seen in Figure 2, the share of small businesses employing information and communication technology (ICT) specialists is only around one-eighth that of large companies. This deficit in specialised managerial talent poses a hindrance to the ability of MSMEs to identify key sectors where they have a competitive advantage.

Figure 2: Share of businesses that offered positions for ICT specialists in OECD countries

Source: Authors’ calculation (simple average across nations) using OECD ICT Access and Use by Business dataset[15]

Inadequate financial resources

Access to capital is key to ensuring that MSMEs constantly update their production processes with global standards. An estimated 65 million formal MSMEs (about 40 percent of all enterprises) are credit constrained.[c] The potential demand for MSME finance is estimated to be around US$8.9 trillion. Of this, a staggering US$5.2 trillion is unmet.[16] This lack of access to capital inhibits MSMEs from investing in high-quality infrastructure and managerial staff, inhibiting their ability to build on specialisations, identify new markets, and get better integrated into the GVC ecosystem.

The COVID-19 pandemic has further aggravated this financing gap. The volatilities induced by the sudden economic contraction caused due to COVID-19 have resulted in pushing several MSMEs to the brink of bankruptcy. It is important to note that MSMEs were affected more during the pandemic than the larger companies. For example, in the East Asia and Pacific region, the monthly sales of MSMEs fell by 7–23 percentage points more than large firms.[17] This has resulted in reducing labour production and weakening the entire structure of the economy in developing countries.[18] Therefore, access to capital is of key importance for MSMEs to fully revive and integrate with the broader GVC ecosystem.

The Role of the G20

The G20 can play a significant role in formulating policy guidelines for developing economies to help boost MSME participation in GVCs. Home to two-thirds of the world’s population,[19] G20 countries act as a nexus point for both advanced and emerging economies. The grouping can, therefore, help in aligning the policies of nations across the various components of the GVC to promote the increased participation of MSMEs. Further, G20 nations contribute about 83 percent of the GVC and will thus be able to influence a substantial portion of world trade.[d]

While the G20 is best positioned to formulate guiding policies, it is necessary to address the fundamental question of why increased participation of MSMEs in GVCs is desirable for G20 nations, specifically amid the increasing sentiment towards protectionism worldwide.

Despite the increasing protectionism, the weighted average global effectively applied tariff rates have fallen from 1.86 percent to 1.52 percent between 2016 and 2020.[e] This is because GVCs have transformed global production. Approximately 50 percent of the total global output of goods and services are intermediate inputs[20] and around 70 percent of the trade flows involve GVCs.[21] However, during the COVID-19 pandemic, the fault lines of GVCs were exposed, as the free movement of goods was curtailed. This has called for increased resilience of the supply chains via geographic decentralisation. Decentralisation must be taken upon in a sustainable manner, with each region assured of basic self-sufficiency. This will also aid in keeping up with growing regional consumer demands.[22] Regional[f] decentralisation of GVCs will require the support of MSMEs as they are the primary producers in several developing nations. Given the G20 nations’ prominence in GVCs, policy interventions of the G20 will be key in strengthening the MSMEs of developing nations, which will not only increase GVC resilience but also raise the standard of living of the developing nations involved.[23]

In 2021, at the G20 summit in Italy, member nations agreed on a non-binding policy toolkit for promoting sustainable development by supporting the digitalisation of MSMEs and integrating them into the global economy.[24] While broad policy guidelines were highlighted at the 2021 summit, this brief proposes a targeted set of policy recommendations, that can be implemented by the G20 forum to help enhance MSME participation in GVCs. While the policy recommendations apply to all economies, special focus is to be given to MSMEs from LDCs to help improve their integration into the global economy.

Recommendations to the G20

Support for MSMEs to upgrade technology, awareness, and skill

One of the greatest challenges preventing MSME participation in GVCs is the lack of adequate production technologies and digital infrastructure. A dedicated platform could be created under the Business20 (B20) for the benefit of MSMEs. This platform can be used to provide MSMEs with the necessary information on the trends in production technology and digital innovations. The platform could also support research to identify cost-effective adaptations of emerging technological trends, to enable affordability for MSMEs.

Further, under the B20, dedicated sector-specific networking sessions could be held between large companies and MSMEs to help the former identify MSMEs that could support them with the supply of ancillary products and services. This would also enhance the exposure of MSMEs to the needs of large industries, increasing their level of awareness about the key success factors for participating in GVCs. Such sessions would also equip MSMEs with the managerial know-how to identify market trends and increase the depth of their participation in GVCs.

To enhance digital skills, the G20 may also constitute an ‘MSME Digital Skills Fund’ to organise knowledge initiatives to help MSMEs with the basics of key digital technologies such as supply chain management software, IoT-based monitoring of supply chain, data-analytics–driven inventory/cost management and much more. The fund could also support skilling camps to help MSME employees upgrade their digital skills and literacy.

Priority colocation of MSMEs with large manufacturers in industrial clusters

MSMEs could be colocated with large manufacturers investing globally; in particular, MSMEs could be positioned as ancillary component manufacturers to large companies, specifically in advanced sectors such as defence and aerospace manufacturing, semiconductor fabrication, electronics manufacturing, and automobile manufacturing. This would create a mutually beneficial synergy between large anchor investors and MSMEs, enabling the growth of both segments of the manufacturing sector. Specialised sector-specific MSME clusters result in increased knowledge sharing, which in turn leads to greater innovation, fuelling further economic growth.[25]

For example, in the Indian state of Tamil Nadu, major anchor investments by leading Korean, American, and French-Japanese automobile manufacturers have a base of over 395 vendors, employing over 300,000 people. This ecosystem has resulted in an 11.3 percent compounded annual growth rate in value addition in the automobile cluster in 1990-1991 (financial year from April 1990 to March 1991) and 2018-2019 (financial year from April 2018 to March 2019).[g]

Government-backed credit guarantee schemes for MSMEs expanding in foreign markets[26]

MSMEs often face difficulty in exporting to foreign markets, specifically to developed economies. A prime reason for this is the need for a plethora of certifications and high-quality standards. Further, understanding foreign markets and gathering necessary business intelligence is a costly affair for most MSMEs. To help MSMEs secure the necessary certifications by meeting global standards, governments could consider providing collateral-free loans in export-oriented sectors.

Improving access to finance for MSMEs via digital innovations[27]

Digital financial services (DFS) can act as a key enabler to enhance access to finance for MSMEs. In particular, emerging fintech solutions such as big data analytics of credit and cash-flow history of companies will be a great boost to improve the coverage of formal credit to MSMEs. These technologies will enable financial organisations to take calculated risks while lending, without requiring the backing of high-value collaterals.

Apart from uncollateralised loans, DFS solutions, such as digital supply chain finance and digital trade finance, will also provide great impetus to MSME financing. With the digitalisation of the supply chain processes, financial institutions will be able to employ AI–machine learning techniques to analyse the inventory and cash-flow cycles of MSMEs to determine appropriate loan amounts and interest rates. This will greatly simplify the loan application process for MSMEs while taking due consideration of their risk exposures.

Similarly, with the digitalisation of cross-border trade processes, banks will have better visibility on the processes and documentation involved in cross-border transactions between MSMEs and their buyers abroad. This availability of information can reduce the complexity of the trade finance application process and improve financial access to MSMEs.[28]

To enable the success of the aforementioned digital solutions, the G20 could set up a knowledge-sharing platform to support LDCs and emerging economies in building the necessary interoperable technology stack to support the digitalisation of trade processes, tax and accounting records, and other relevant documentation. This should complement a simplified trade/tax documentation process to make the platform more user-friendly.

Developing MSME-GVC participation-enabling index for developing countries

A global MSME-GVC participation index could be inaugurated to track the participation of MSMEs across various nations in GVCs. The index could also take into consideration aspects such as the sector-wise share of domestic value addition that is exported, the sector-wise share of consumption of imported sub-components in the production process, employment generated, access to credit, and the number of export/import linkages with other countries. Such an index will provide a benchmark for countries to understand where they stand globally and areas with potential for improvement.

Creating a pool of funds to generate a greater understanding of MSMEs

A dedicated fund may be set up to harmonise statistics[29] across various nations with regard to MSMEs and compile the annual MSME–GVC participation index. Apart from the index, the fund may be used to conduct an in-depth analysis of the best practices adopted in various countries to enhance the inclusion of MSMEs into GVCs and the broader global digital economy. It may also be used to host networking events on forums such as the G20 on MSMEs and exchange knowledge[30] on country experiences compiled from various funded research studies.

Attribution: Shubham Gupta and Akshay Natteri Mangadu, “Enhancing the Capacity of MSMEs to Participate in Global Value Chains,” T20 Policy Brief, May 2023.

Endnotes

[a] Small companies refer to firms with less than 50 employees, medium companies refer to those with 50 to 250 employees, and large companies refer to those with 250 or more employees.

[b] As of 2017. Authors’ calculation (simple average across nations) using OECD ICT Access and use by Business dataset.

[c] Credit-constrained firms include those with no external funding and whose application for loans have been rejected or that were discouraged from applying for loans. It also includes firms with external funding that were discouraged from applying for loans, or whose loan applications were rejected, or only partially approved.

[d] Authors’ calculation based on Casella, Bruno, Richard Bolwijn, Daniel Moran, and Keiichiro Kanemoto. “Improving the analysis of global value chains: the UNCTAD-Eora Database.” Transnational Corporations 26, no. 3 (2019): 115-142.

[e] Authors’ calculations based on data from World Trade Organization Integrated Database and United Nations COMTRADE. Accessed via World Bank WITS on 22 March 2023 (https://wits.worldbank.org/). In terms of simple average of tariffs within each country, the decline was from 3.24 percent to 2.85 percent between 2016 and 2020.

[f] Region typically refers to well-connected set of countries in the vicinity of each other, such as Southeast Asia or North America.

[g] Authors’ calculation based on the Annual Survey of Industries, Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation, Government of India.

[1] “Global Value Chains,” Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), accessed March 21, 2023.

[2] “Global Value Chains and Trade,” Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, accessed March 21, 2023.

[3] Claire H. Hollweg, “Global Value Chains and Employment in Developing Economies,” in Global Value Chain Development Report 2019: Technological Innovation, Supply Chain Trade, and Workers in a Globalized World, ed. William Shaw (Geneva: World Trade Organisation, 2019), 63.

[4] Hollweg, “GVC and Employment in Developing Economies,” 69.

[5] Sabyasachi Mitra, Abhijit Sen Gupta, and Atul Sanganeria, “Drivers and Benefits of Enhancing Participation in Global Value Chains: Lessons for India,” Asian Development Bank South Asia Working Paper Series, no.79 (December 2020): 5.

[6] Hollweg, “GVC and Employment in Developing Economies,” 76.

[7] James Fox, “As Chinese Lockdowns Continue and Salaries Rise, Footwear Manufacture Shifts to Vietnam,” ASEAN Business News (Dezan Shira & Associates), October 14, 2022.

[8] Fox, “Chinese Lockdowns.”

[9] Yao Wang, “What Are the Biggest Obstacles to Growth of SMEs in Developing Countries? An Empirical Evidence from an Enterprise Survey,” Borsa Istanbul Review 16, no. 3 (September 2016): 172.

[10] Dani Rodrik, “New Technologies, Global Value Chains, and Developing Economies,” National Bureau of Economic Research, No. w25164 (October 2018): 8.

[11] https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=ICT_BUS

[12] Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), Enhancing the Contributions of SMEs in a Global and Digitalised Economy, June 2017, Paris, OECD, 2017.

[13] Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (ESCAP), Digital and Sustainable Trade Facilitation: Global Report 2021, February 2022, Bangkok, United Nations, 2022.

[14] Emmanuelle Ganne and Kathryn Lundquist, “The Digital Economy, GVCs and SMEs,” in Global Value Chain Development Report 2019: Technological Innovation, Supply Chain Trade, and Workers in a Globalized World, ed. William Shaw (Geneva: World Trade Organisation, 2019), 134.

[15] https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=ICT_BUS

[16] International Finance Corporation, MSME Finance Gap: Assessment of the Shortfalls and Opportunities in Financing Micro, Small, and Medium Enterprises in Emerging Markets, January 2017, Washington DC, World Bank Group, 2017.

[17] “NPL Resolution, Insolvency and SMEs in Post-COVID-19 Times,” The World Bank, accessed March 21, 2023.

[18] United Nations Regional Commissions, COVID-19: Towards an Inclusive, Resilient and Green Recovery—Building Back Better Through Regional Cooperation, May 2020, Santiago, United Nations, 2020.

[19] “National Portal of India,” Government of India, accessed May 12, 2023.

[20] Taiji Furusawa and Lili Yan Ing, “G20’s Roles in Improving the Resilience of Supply Chains,” in New Normal, New Technologies, New Financing, eds. Lili Yan Ing and Dani Rodrik (Jakarta: Economic Research Institute for ASEAN and East Asia, 2022), 51.

[22] Willy C Shih, “Global Supply Chains in a Post-Pandemic World,” Harvard Business Review 98, no. 5 (2020): 82–89.

[23] Daria Taglioni, “Towards a G20 Strategy for Promoting Inclusive Global Value Chains,” World Bank, September 6, 2016.

[26] United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), The COVID-19 Pandemic Impact on Micro, Small, and Medium-sized Enterprises: Market Access Challenges and Competition Policy, COVID-19 Response, January 2022, Geneva, United Nations, 2022.

[27] Global Partnership for Financial Inclusion, Promoting Digital and Innovative SME Financing, May 2020, Washington DC, World Bank Group, 2020.

[28] Global Partnership for Financial Inclusion, “SME Financing,” 28.

[29] Amare Abawa Esubalew and A. Raghurama, “Revisiting the Global Definitions of MSMEs: Parametric and Standardization Issues,” Asian Journal of Research in Business Economics and Management 7, no. 8 (2017): 429.

[30] Ayodotun Stephen Ibidunni, Aanuoluwa Ilerioluwa Kolawole, Maxwell Ayodele Olokundun, and Mercy E. Ogbari, “Knowledge Transfer and Innovation Performance of Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs): An Informal Economy Analysis,” Heliyon 6, no. 8 (2020): 1.

Also see, Amitabh Anand, Birgit Muskat, Andrew Creed, Ambika Zutshi, and Anikó Csepregi, “Knowledge Sharing, Knowledge Transfer and SMEs: Evolution, Antecedents, Outcomes and Directions,” Personnel Review 50, no. 9 (2021): 1873.