Task Force 6: Accelerating SDGs: Exploring New Pathways to the 2030 Agenda

Reckless expansion of unsustainable land use, largely induced by supply chains, has led to deforestation, ecosystem conversion and environmental degradation, which in turn have caused an unprecedented decline in biodiversity and disruption of ecosystem services. There is growing awareness of the need for global policy, for regulatory, private and financial sector action, to reverse this trend. However, solutions are being developed with little regard, if at all, to local actors and their capacities, interests and crucial role in protecting natural resources. Active involvement and empowerment of local actors is critical. The G20 is uniquely positioned to foster local governance and leadership in sustainable natural resource management as part of national and global supply chains. Policies, regulations, and instruments aiming at the conservation of natural resources, forests and biodiversity must involve and invest in local actors to a greater extent.

1. The Challenge

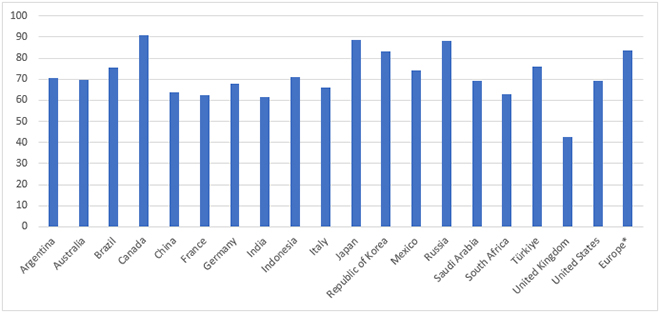

Around US$ 44 trillion, more than half of the world’s gross domestic product (GDP), depends on natural resources such as water, forests, and minerals.[1] Uncontrolled exploitation of forests, ecosystems, and natural resources has resulted in unprecedented biodiversity decline and ecosystem services disruption,[2] and this is true for many G20 countries (Figure 1). Logging, land conversion, and land use for agriculture linked to food, fibre, feed, and wood supply chains account for 22 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions.[3] Climate change adversely affects natural resources and biodiversity conservation efforts. Biodiversity loss and climate change are twin crises and must be addressed together, including their combined social impacts.[4]

Figure 1. Biodiversity Intactness Index of G20 countries in 2020 (%)

Source: Biodiversity Intactness Index database, under the projected scenario ‘Middle of the Road’ development (SSP2).[5],[a]

For decades now, governments and civil society organisations have been working on generating local income on the basis of sustainable natural resource management. Various environmental and social programmes and initiatives of development cooperation have been launched. Community empowerment to decide on the use of natural resources started at the end of the 1980s,[9] and local actors’ key role in forest governance has been increasingly recognised since. (No doubt, the results are not yet fully satisfactory in terms of local benefit generation and empowerment of local stakeholders.[10]) Approaches with local actors’ participation include joint forest management,[11] community forestry[12] and community management of further natural resources,[13] agro-forestry,[14] bio-economy,[15] participatory organic certification,[16] collaborative monitoring of natural resources,[17] payments for environmental/ecosystem services,[18] and other initiatives.[19]

The Nagoya Protocol on Access and Benefit Sharing (ABS)[b],[20] and the Free Prior and Informed Consent (FPICs) are two outstanding global mechanisms[c],[21] that are shifting ownership and benefits towards local actors. At the Effective Development Cooperation Summit in Geneva in December 2022, several donors[d] contributing to biodiversity conservation endorsed a statement supporting locally-led development.[22] Through its Bhopal declaration in January 2023, the T20 also emphasised the importance of local stakeholders for G20 countries to achieve the SDGs.[23] This growing awareness for locally-led development is remarkable, but still mostly limited to the environmental and development cooperation communities.

Crucial economic and finance policies targeting corporate actors and financial institutions, are also increasingly recognising and addressing climate change and biodiversity loss as key threats. These include voluntary frameworks as well as mandatory legislation relating to supply chains and sustainable finance.[e] A key goal is to shift from unsustainable to sustainable economic activities, facilitating the transformation to a climate-resilient economy in alignment with the Paris Agreement. By de-risking sustainable activities, direct investment can be facilitated.[24]

However, these legislations are mainly developed by finance experts and economists with little knowledge of the realities of local actors in developing countries and upstream supply chains. Local actors come into play only as “workers in the value chain” or “affected communities” (see for instance, the European draft disclosure standards).[25] Relevant economic and finance legislations do not yet enable the enormous potential of local actors to take a leading role in climate, biodiversity and natural resource governance. This gap was also identified in the roundtable discussion of the G20 SFWG, involving the private sector, in April 2022.[26]

Empowered local actors are vital to mitigating the global climate and biodiversity crises, and to the success of the global sustainability transition. It is of utmost importance to structurally empower local actors through improved access to finance and business opportunities as well as capacity-building. Policies and legislations need to emphasise the role of local actors and prepare the ground for formalised and financially beneficial roles for local organisations (see Box 1).

2. The G20’s Role

The G20 is in a unique position to foster a just sustainability transition that includes the conservation and sustainable management of biodiversity and natural resources along entire supply chains. It can facilitate increased investments in local governance, empowerment and leadership, especially in developing and emerging economies upstream. The first G20 Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors Meeting in February 2023 released a statement that said in part: “We are committed to advancing financial inclusion and ensuring that no one is left behind.”[27] Also, seven G20 countries have endorsed the Donor Statement on Supporting Locally Led Development.[28] In various other contexts, the G20 has also made references and commitments towards a just transition, and is therefore ideally positioned to promote local actors as active agents in this transition.

The Indian G20 presidency is set to foster collaboration on sustainable global value chains that meet common social, environmental and economic objectives, including the reduction of natural resource depletion and social inequalities.[29] Brazil and South Africa, whose presidencies are to follow India’s, are also likely to prioritise these objectives. Alignment across the three presidencies is essential to substantially shift attention towards local actors for a just and sustainable transition.

3. Recommendations to the G20

- Put local governance and empowerment of local stakeholders at the top of the agenda to effectively address climate change and biodiversity loss. Finance flows urgently need to trickle down to stakeholders at the local level, especially in the emerging economies of the G20 and developing countries across the world;

- Endorse all relevant international commitments that call for strengthening local actors, such as the Donor Statement on Supporting Locally Led Development and the Principles for Locally Led Adaption;,[30]

- Promote strong participation of the private and financial sectors in just sustainability transition, as was discussed at the private sector roundtable discussion of the SFWG;[31]

- Design a just transition framework, with key standards and impact measurement criteria that are applicable across multiple jurisdictions and helpful to financial sector decision-makers;[32]

- Promote mandatory supply chain and sustainable finance legislations to facilitate the shift to sustainable economic activities and call for the structural integration of local actors as key agents (see Box 1);

- Increase access to funding and compensation for local actors protecting biodiversity and natural resources. Mechanisms such as the REDD+[f],[33] need to be further developed and simplified for financial flows to facilitate better and faster support for stakeholders at the local level. Support the further development of new tools and mechanisms to channel compensational funding.[g],[34] In general, efforts to structurally implement payments for ecosystem services[h] should be renewed.[35]

- Foster carbon finance instruments that require local organisations to participate in projects, benefit from and even co-lead them.[i] Implementation and scaling of biodiversity offsets[36] could be further explored to support locally-led biodiversity conservation. (Offsets, or compensatory efforts following inevitable biodiversity loss from developmental activity, should be limited to unavoidable impacts and should be an addition to prevention and mitigation measures.)

- Foster action to collect and make public data on scattered and little supported local initiatives, especially those that specifically target marginalised groups or women.

| BOX 1: Sustainable Finance Regulations, Transparency and Local Verification Schemes

Policymakers and financial actors are increasingly developing mandatory sustainable finance instruments to redirect private and public capital flows towards more sustainable activities. Such instruments include disclosure (transparency) on environmental, social and governance (ESG) factors as a key element. The global market for transparency and information is thus growing. Transparency is essential for certified organic, environmentally friendly, fair-trade, and sustainable products and voluntary carbon markets.[37] It is a persisting challenge for certifiers and data providers to uncover green-washing and fraud.[38] More knowledge of specific local environmental impacts and socio-economic dynamics is needed.[39] Local organisations geographically close[j] to areas where ecosystem conversion is occurring have a unique understanding of the economics of the process. Local actors could be granted formalised roles as verifiers of disclosed information on ecosystem conversion or degradation within disclosure frameworks. They would thereby be empowered, could create new business opportunities and thus better drive local sustainable development at, for example, forest frontiers. At the same time, they could support the push for more transparency on deforestation and ecosystem conversion and degradation by improving upon the reliability of disclosed information. This would help companies in the supply chain to establish their compliance. Local knowledge can make data more reliable and less prone to wrongful reporting, especially in remote areas and where land tenure schemes are still weak. Verification could combine remote sensing data and tools, that as stand-alone measures, do not yet cover all transparency needs, such as tracing products of international supply chains back to the farm.[k],[40] A framework for local verification of information should be created within the application guidelines for auditors in all globally relevant disclosure frameworks in development.[l] Development cooperation could help transform such services into income opportunities for local actor organisations in developing countries and emerging economies. |

Attribution: Sukanya Das et al., “Enabling Local Governance to Mitigate the Climate and Biodiversity Crises,” T20 Policy Brief, July 2023.

Endnotes

[a] Biodiversity Intactness Index measures biodiversity change, with 100 percent indicating a pristine ecosystem. The figure for Europe indicates all of Europe, not just those countries in the EU which are G20 members.

[b]The Nagoya Protocol on Access and Benefit Sharing (ABS)—or the ‘Nagoya Protocol on Access to Genetic Resources and the Fair and Equitable Sharing of Benefits Arising from their Utilization to the Convention on Biological Diversity’—is an international agreement that aims to share the benefits from the utilisation of genetic resources in a fair and equitable way. It entered into force on 12 October 2014.

[c] The Free Prior and Informed Consent – An Indigenous Peoples’ Right and a Good Practice for Local Communities is a principle protected by international human rights standards that state, ‘all peoples have the right to self-determination’ and ‘all peoples have the right to freely pursue their economic, social and cultural development’.

[d] These comprised Australia, Canada, Denmark, Estonia, France, Iceland, Ireland, Japan, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Korea, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Lithuania; the Netherlands; Norway; the Spanish Cooperation for Development; the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation; the United Kingdom’s Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office; and the United States Agency for International Development.

[e]In the EU, for example, supply chain and sustainable finance regulatory measures are being developed under the Green New Deal to reduce the carbon and biodiversity footprint of the EU. At the global level, examples include the International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB), Target 15 of the Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF), and the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI).

[f] REDD+ (Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and forest Degradation – the ‘+’ refers to other forest activities) is a framework created by the UN Framework Convention for Climate Change (UNFCCC) Conference of the Parties (COP) to guide activities in the forest sector that reduce such emissions and support sustainable management of forests and conservation and enhancement of forest carbon stocks in developing countries.

[g]An example of this is the GainForestTM initiative, a decentralised fund using artificial intelligence to measure and reward sustainable nature stewardship.

[h] Payments for Ecosystem Services (PES) are incentives provided to local actors for managing natural resources in a way that ecosystem or environmental services are protected. The mechanism can help generate investments for integrated natural resource management and contribute to the well-being of poor and marginalised groups.

[i]The carbon credit market is growing among farming communities, and monetisation of carbon credit can be the nudge to incentivise or scale climate-smart agriculture among smallholder farmers in developing countries.

[j] ‘Local organisations’ can be defined as representative organisations based in, or having geographical proximity to, specific (sub-national) jurisdictions. From a downstream point of view these are areas typically upstream supply chains, where ecological and social impact of economic activities takes place. Examples are municipalities or social movements, smallholder and community associations.

[k]Traders often source more than 40 percent of commodities “indirectly” via local intermediaries – a major blind spot for sustainable sourcing initiatives.

[l] Examples of such disclosure frameworks would be the Global Reporting Initiatives (GRI), the International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB), the task force on Nature-related Financial Disclosures, the task force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures (TCFD), the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and the European Sustainability Reporting Standards (ESRS).

[1] “Half of World’s GDP Moderately or Highly Dependent on Nature, Says New Report,” News Releases, WEF, January 19, 2020, https://www.weforum.org/press/2020/01/half-of-world-s-gdp-moderately-or-highly-dependent-on-nature-says-new-report/

[2] Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services, Global assessment report on biodiversity and ecosystem services, 2019, IPBES, https://zenodo.org/record/6417333; Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Mitigation of Climate Change Working Group III, Contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report of the IPCC, 2022, IPCC, https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg3/; Hannah Ritchie and Max Roser, “Forests and Deforestation,” Deforestation – Forests, Our World in Data, 2021, https://ourworldindata.org/deforestation#how-much-deforestation-occurs-each-year; Pia Sethi, Vidhu Kapur, Sukanya Das, Balwant Singh, “Losing the benefits of forests to degradation?,” Forest and Biodiversity, TERI, July 12, 2018, https://www.teriin.org/casestudies/losing-benefits-forests-degradation; Genevieve Lim, Thiam Hee Ng and Dulce Zara, “Implementing a Green Recovery in Southeast Asia,” ADB Briefs, March 2021, https://www.adb.org/publications/green-recovery-southeast-asia

[3] United Nations Climate Change High-Level Climate Champions et al, Why Net Zero Needs Zero Deforestation Now, June, 2022, UN Climate Change High-Level Climate Champions, Global Canopy, The Accountability Framework initiative, WWF and the Science Based Targets initiative, https://climatechampions.unfccc.int/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Why-net-zero-needs-zero-deforestation-now-June-2022.pdf

[4] Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services, Tackling Biodiversity & Climate Crises Together and Their Combined Social Impacts, Press release, 2021, https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/blog/2021/06/tackling-biodiversity-climate-crises-together-and-their-combined-social-impacts/

[5] Helen Phillips et al., The Biodiversity Intactness Index – country, region and global-level summaries for the year 1970 to 2050 under various scenarios, 2021, Natural History Museum Data Portal, https://data.nhm.ac.uk/dataset/bii-bte

[6] United Nations Development Programme, G20 Sustainable Finance Working Group Private Sector Roundtable, April 27-28, 2022, UNDP, https://g20sfwg.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/Final.-G20-Sustainable-Finance-PSR-2022-summary.pdf

[7] Benno Pokorny, Pablo Pacheco, Wil de Jong & Steffen Karl Entenmann, “Forest frontiers out of control: The long-term effects of discourses, policies, and markets on conservation and development of the Brazilian Amazon,” Ambio, 2199–2223, (October 12, 2021), https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s13280-021-01637-4; Gabriel Medina and Claudio Barbosa, “The Neglected Solutions: Local Farming Systems for Sustainable Development in the Amazon,” Research Gate, (March 2023), https://www.researchgate.net/publication/369255403_The_Neglected_Solutions_Local_Farming_Systems_for_Sustainable_Development_in_the_Amazon; Benno Pokorny et al., “Market-based conservation of the Amazonian forests: Revisiting win–win expectations,” Geoforum, Volume 43, Issue 3, (May, 2012): 387-401, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0016718510000928?via%3Dihub

[8] Walter V. Reid et al., Millenium Ecoysystem Assessment, Ecosystems and human well-being: synthesis, Island Press, January 2005, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/297563785_Millennium_Ecosystem_Assessment_Ecosystems_and_human_well-being_synthesis

[9] Ruchi Badola, Syed Ainul Hussain, Pariva Dobriyal and Shivani Barthwal, “Assessing the effectiveness of policies in sustaining and promoting ecosystem services in the Indian Himalayas,” International Journal of Biodiversity Science, Ecosystem Services & Management, Vol. 11, No. 3, (2015): 216–224, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/21513732.2015.1030694

[10] Gabriel Medina, Benno Pokorny and Bruce Campbell, “Forest governance in the Amazon: Favoring the emergence of local management systems,” World Development, Volume 149, (2022), https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0305750X21003119?via%3Dihub

[11]Masahiko Ota, Misa Masuda and Kaori Shiga, “Payment for What? The Realities of Forestry Benefit Sharing Under Joint Forest Management in a Major Teak Plantation Region of Java, Indonesia,” Small-scale Forestry, 19, 439-460, (June 4, 2020), https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11842-020-09446-5; Masahiko Ota, “From joint forest management to more smallholder-based community forestry: prospects and challenges in Java, Indonesia,” Journal of Forest Research, Volume 24, Issue 6, (2019), https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/13416979.2019.1685063?journalCode=tjfr20

[12] K.F.Wiersum, Encyclopedia of Forest Sciences, Community Forestry, ScienceDirect, 2004, https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/earth-and-planetary-sciences/community-forestry

[13] Diang-Tao Wu et al.,“Cordyceps collected from Bhutan, an appropriate alternative of Cordyceps sinensis,” Scientific Reports 6, 2016, https://www.nature.com/articles/srep37668

[14] “World Agroforestry”, Center for International Forestry Research, Agroforestry, CIFOR-ICRAF, accessed May 22, 2023, https://www.cifor-icraf.org/research/topic/agroforestry/

[15] Thomas Vogelpohl and Annette Toeller,“Perspectives on the bioeconomy as an emerging policy field,” Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 23:2, 143-151, (2021), https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/1523908X.2021.1901394

[16] Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations, Organic Agriculture, FAO, last modified 2023, https://www.fao.org/organicag/oa-faq/oa-faq5/en/; Apoorve Khandelwal et al., “Scaling up sustainability through new product categories and certification: Two cases from India,” Sec. Land, Livelihoods and Food Security, Volume no. 6, (December 1, 2022), https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fsufs.2022.1014691/full

[17] Moabi Democratic Republic of the Congo Initiative, accessed April 1, 2023, https://rdc.moabi.org/en/

[18] “Markets and payments for environmental services”, Natural Resource Management, International Institute for Environment and Development-IIED, accessed May 22, 2023, https://www.iied.org/markets-payments-for-environmental-services

[19] Gabriel Medina et al., “Searching for Novel Sustainability Initiatives in Amazonia,” Sustainability, 14(16), (2022), https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/14/16/10299

[20] “About the Nagoya Protocol,” Convention on Biological Diversity-CBD, 2015, https://www.cbd.int/abs/about/default.shtml/

[21] “Free Prior and Informed Consent – An Indigenous Peoples’ right and a good practice for local communities – FAO,” United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Indigenous Peoples, UN, October 2016, https://www.un.org/development/desa/indigenouspeoples/publications/2016/10/free-prior-and-informed-consent-an-indigenous-peoples-right-and-a-good-practice-for-local-communities-fao/

[22] “Donor Statement on Supporting Locally Led Development, ”United States Agency for International Development-USAID, Washington DC, December 13, 2022, https://www.usaid.gov/localization/donor-statement-on-supporting-locally-led-development

[23] TNPSC Thervu Pettagam,“Bhopal Declaration,” News photo, January 21, 2023, https://www.tnpscthervupettagam.com/currentaffairs-detail/bhopal-declaration

[24] Neha Khanna and Dhruba Purkayastha, “Mobilizing Green Finance while Managing Climate Finance Risk in India,” Climate Policy Initiative, 2022, https://www.climatepolicyinitiative.org/publication/mobilizing-green-finance-while-managing-climate-finance-risk-in-india/

[25] European Commission, European sustainability reporting standards – first set, 2023, https://ec.europa.eu/info/law/better-regulation/have-your-say/initiatives/13765-European-sustainability-reporting-standards-first-set_en

[26] UNDP, G20 Sustainable Finance Private Sector Roundtable, April 27-28, 2022, UNDP, https://www.undp.org/geneva/events/g20-sustainable-finance-private-sector-roundtable-27/28-april-2022

[27] G20, Chair’s Summary and Outcome Document, First G20 Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors Meeting, Bengaluru, February 24-25, 2023, www.g20.org/content/dam/gtwenty/gtwenty_new/document/1st%20FMCBG%20Chair%20Summary.pdf

[28] USAID, Donor Statement on Supporting Locally Led Development, December 13, 2022, USAID, https://www.usaid.gov/localization/donor-statement-on-supporting-locally-led-development

[29] Rijit Sengupta,“View: India G20 for a collaborative initiative on sustainable global value chains,” The Economic Times, January 10, 2023, https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/india/view-india-g20-for-a-collaborative-initiative-on-sustainable-global-value-chains/articleshow/96881881.cms?from=mdr

[30] USAID, Donor Statement on Supporting Locally Led Development, December 13, 2022, USAID, https://www.usaid.gov/localization/donor-statement-on-supporting-locally-led-development; “Principles for locally led adaptation,” IIED, accessed 2021, https://www.iied.org/principles-for-locally-led-adaptation

[31] UNDP, G20 Sustainable Finance Private Sector Roundtable, April 27-28, 2022, UNDP, https://www.undp.org/geneva/events/g20-sustainable-finance-private-sector-roundtable-27/28-april-2022

[32] Promit Mookherjee, Ed., Bridging the Climate Finance Gap: Catalysing Private Capital for Developing and Emerging Economies, Observer Research Foundation, March 4, 2023, https://www.orfonline.org/research/bridging-the-climate-finance-gap/

[33] “What is REDD,” UNCC, accessed May 20 2023, https://unfccc.int/topics/land-use/workstreams/redd/what-is-redd

[34] “Transparent Monitoring for a Greener Future,” Gainforest, accessed May 20 2023, https://gainforest.app/

[35] Esteban Brenes, Francisco Alpizar and Róger Madrigal-Ballestero, Bridging the Policy and Investment Gap for Payment for Ecosystem Services: Learning from Costa Rican Experience and Roads Ahead, Technical Report, 2016, The Green Growth Institute, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/311535670_Bridging_the_Policy_and_Investment_Gap_for_Payment_for_Ecosystem_Services_Learning_from_the_Costa_Rican_Experience_and_Roads_Ahead

[36] International Union for Conservation of Nature, Biodiversity offsets, IUCN Issues Brief, 2021, https://www.iucn.org/resources/issues-brief/biodiversity-offsets

[37] European Commission, Report: Study on Certification and Verification Schemes in the Forest Sector and for Wood-based Products, 2021, EU, https://www.atibt.org/files/upload/news/Certification/etude_certification.pdf

[38] Patrick Greenfield, Revealed: more than 90% of rainforest carbon offsets by biggest certifier are worthless, analysis shows, The Guardian, January 18, 2023, https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2023/jan/18/revealed-forest-carbon-offsets-biggest-provider-worthless-verra-aoe; “Verra Fact Check of Die Zeit Article,” Verra, January 27, 2023.

[39] Hoch et al., Key actions to safeguard against deforestation in the EU Taxonomy, Policy Recommendations, Climate & Company, 2022. Raphael Tietmeyer et., Comparative Analysis of Upcoming Disclosure Standards: Key Steps to Raise Ambition (and the case of deforestation), Policy Recommendations, Climate & Company, 2023.

[40] Erasmus Ermgassen et al.,“Addressing indirect sourcing in zero-deforestation commodity supply chains,” Science Advances, Vol.8, (April 29, 2022):17.