Task Force 6: Accelerating SDGs: Exploring New Pathways to the 2030 Agenda

Abstract

International agencies have expressed concerns about the welfare of youth not in employment, education, or training (NEET) considering unprotected work in the formal sector, informal employment in the informal sector, and skill gaps, among others. Alternatives to inclusively harness the demographic advantage are required for a better transition to decent work security. This Policy Brief recommends harnessing the strategy of Development and Entrepreneurship for Sustainable Habitats (DESH). It can be modelled for the G20 with reference to India’s Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA), designed for resource-poor rural populations in need of employment. DESH will aim to give employment to skilled NEET youth for guaranteed job days a year against a country’s prioritised shelf of sustainable habitat work.

1. The Challenge

The recent Future of Work report by the World Economic Forum (WEF) calls for the wider inclusion of educated young people in decent work and social security.[a] Other earlier reports by organisations such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the World Bank, the International Labour Organisation (ILO), and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) have found that unemployment and underemployment rates are on the rise because of disruptions caused by technology, pandemics, and other vicissitudes in the economy at large. This Policy Brief attempts to draw on the mandates of Agenda 2030 and the Addis Ababa Action Agenda (AAAA) to provide decent work to post-secondary educated young people and youth who are not in employment, education, or training (NEET) because of multiple vulnerabilities.

The aim is to accelerate the SDGs, particularly in habitats with social, economic, and environmental vulnerabilities. The proposal is framed in a new policy construct, namely, Development and Entrepreneurship for Sustainable Habitats (DESH), for harmonious habitat outcomes in terrestrial and marine settings. Outcome indicators will be evident in the balanced development of habitats, together with the protection of the environment, shelter, equity in employment, basic services, climate action, and social infrastructure.

2. The G20’s Role

Building on a succession of G20 declarations (Table 1), the G20’s DESH policy can be backed by a contributory alliance of sorts, comprising governments, businesses, non-government organisations, and international development and funding agencies.

Table 1: G20 Meetings (2013–2023) in Support of the DESH Rationale

| Year | Summit | Key Declaration | Challenge Context |

| 2013 | Saint Petersburg, Russia, 5-6 September | Job creation to counter unemployment and underemployment among young people | Continued global financial crisis since the first G20 summit (1999) and domestic resource mobilisation |

| 2014 | Brisbane, Australia, 15-16 November | Add more than US$2 trillion to the global economy and create millions of jobs by 2018 | Gap mitigation of Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) in developing countries |

| 2015 | Antalya, Turkiye, 15-16 November | Support better integration of young people into the labour market through the promotion of entrepreneurship | Transitioning from MDGs to SDGs and reducing at-risk young people left behind in the labour market by 15 percent by 2025 |

| 2016 | Hangzhou, China, 5 September | Income opportunities for women, youth, and disadvantaged groups through policy integration, open economy, and inclusion | Taking into account the 2030 agenda, the Addis Ababa Action Agenda, and the Paris Agreement |

| 2017 | Hamburg, Germany, 7-8 July | Quality apprenticeship in integrating young people into the labour market | Digital economy, governments, business communities, and partners |

| 2018 | Buenos Aires, Argentina, 30 November-1 December | Work delivered through digital platforms and effectively tackling inequalities | Technological transformation and a menu of policy options for the future of work |

| 2019 | Osaka, Japan, 28-29 June | Data flow and electronic commerce | Trade and investment, environment and energy, development, and health |

| 2020 | Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 21-22 November | Decent jobs for youth, including those in the informal economy and the G20 Youth Roadmap 2025 | Inclusive recovery from the adverse impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic |

| 2021 | Rome, Italy, 30-31 October | SDG localisation, sustainable production, responsible consumption, and affordable access to clean and modern energy | Special drawing rights for improving sustainability, as underlined by the Habitat III New Urban Agenda |

| 2022 | Bali, Indonesia, 15-16 November | Opening up the potential of start-ups by involving the youth, women, the business sector, audit institutions, parliaments, scientists, and labour | Global Biodiversity Framework “Living in Harmony with Nature” under the G20 Financial Inclusion Framework |

Source: Compiled from previous G20 presidencies reports.[b]

In turn, productive assets are expected to not be limited to the following areas:

– Water: installation of water pumps, construction of wells, maintenance of water systems, water harvesting, clean and safe water for all;

– Waste: construction of waste treatment facilities, circular approaches, and wealth generation;

– Energy: installation of renewable energy systems and promotion of energy efficiency;

– Infrastructure: construction of roads and bridges, housing, common facilities, and utilities;

– Transport: intelligent multi-modal public transportation systems and emission control;

– Agriculture: improvement of agricultural systems, such as through precision and climate-smart agriculture

– Environment: protection of green and blue natural habitats, flora and fauna diversity, implementation of conservation measures, and promotion of sustainable practices.

The above measures will have a positive impact on people, the planet, and profit. Besides, human-nature harmony in the growth of sustainable tourism would be more achievable with improvements in the conditions and carrying capacity of habitats under sustainable development for the growth of a sustainable tourism economy, which would provide new opportunities for decent employment of NEET youth.

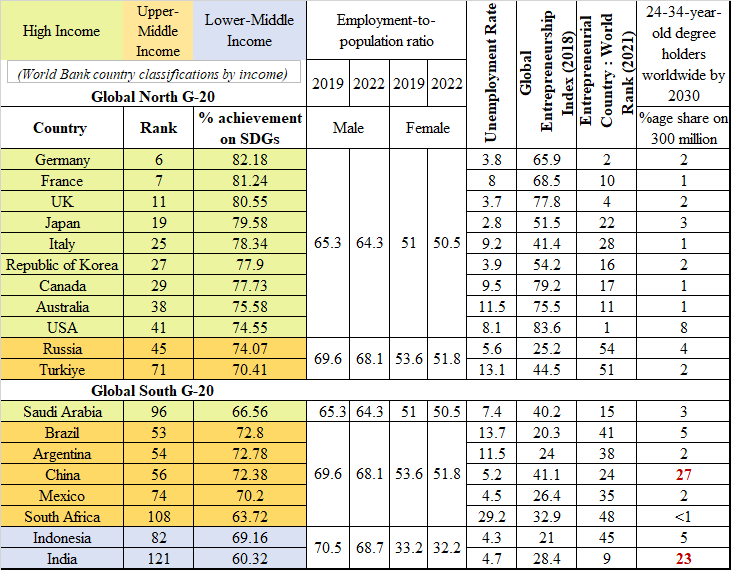

Figure 1: Scope of Inclusion of Young People in Decent Work

Sources: World Bank (blogs.worldbank.org); Sustainable Development Report 2022 (dashboards.sdgindex.org); ILO World Employment and Social Outlook; OECD; World Bank; Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM 2022.2023); Global Entrepreneurship and Development Institute; CEO World Magazine.

Keeping the NEET youth in mind, there needs to be a renewed collaborative thrust in the G20’s convergent role, along with a sustainable financing framework for the adoption of country-relevant DESH policy through the inclusive process of leveraging the demographic advantage for accelerating SDGs.

The G20 Demographic Advantage. The G20 region has a unique demographic advantage, with a large and growing youth population, which provides a huge opportunity to promote sustainable development and entrepreneurship. Both the Global North and Global South G20 countries stand to benefit from a DESH policy. Most importantly, young NEET people can be productively included in local development through new jobs and entrepreneurial opportunities in sustainable habitat development, which can be supported through multilateral cooperation, partnerships, and improved economic growth drivers. For instance, the World Bank (2018) endorsed that investing in youth employment programs is essential to reducing poverty and promoting economic growth. In addition, the ILO (2017) stated that providing financial support for apprenticeships can help reduce unemployment and create more inclusive labour markets. For its part, the OECD (2019) has been in favour of introducing measures for employers to adjust their workforce in response to changing economic conditions, which can help create more job opportunities and stimulate economic growth.

3. Recommendations to the G20

DESH Policy Model. This model is inspired by India’s Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act of India (MGNREGA 2005) and has the following objectives:

- Education, training, and employment-generation for NEET youth, without the regular or contractual labour legalities.

- Asset creation by way of guaranteed 100 days of employment in a financial year for eligible people in the age group of 24–34 years seeking apprenticeship and on-job entrepreneurship opportunities for transitioning to decent work security.

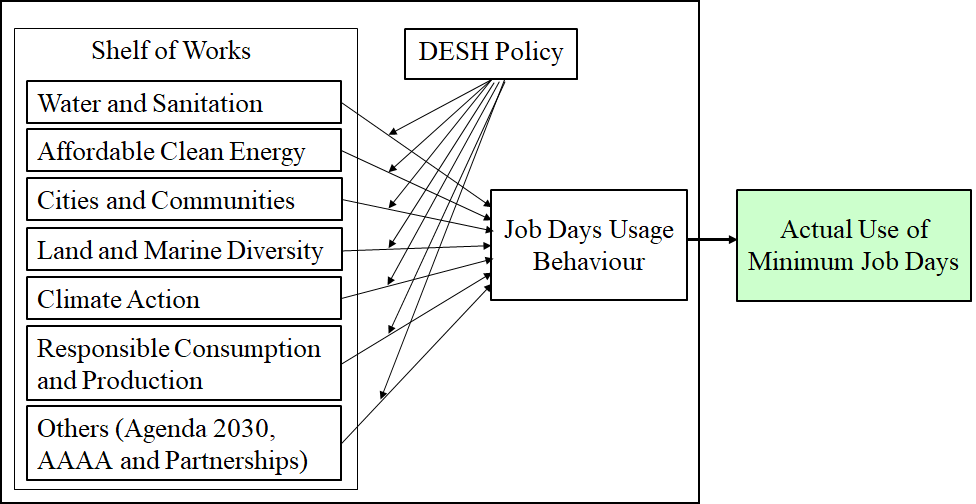

- Local habitat development under the notified shelf of work (Figure 3) in accordance with the SDGs.

- Socio-economic inclusion of diverse groups comprising women, youth, and the disadvantaged.

The DESH Technology Acceptance Model (TAM). The model (see Figure 3) requires the DESH policy (plans, schemes, programs) to significantly mediate the relationship between the dynamic shelf of work and the DESH system usage behaviour of participants in order to strengthen the actual use for effective outcomes. Therefore, a robust and conducive policy system would significantly strengthen TAM relationships, which will facilitate the successful pilot implementation of DESH for the NEET youth and help their transition to decent work and secure labour benefits.

Figure 3: DESH Technology Acceptance Model

Source: Authors’ own

Overall, the model posits addressing youth unemployment and helping young people achieve their economic goals (Petrucci, 2021). At the same time, the strategy can help promote social bonding and increased growth in sustainable tourism by reviving ecologically vulnerable spots that are also preferred destinations for tourists and visitors (Sarkar 2022).

Funding. G20 countries can leverage their transition finance framework of 2022 to fund the DESH policy by considering the local priorities, common G20 North-South DESH goals, country-income categories, and US$ parity, which can roughly be considered as the country-average allocation of approximately US$550 for education, training, certification, technology systems, governance, and support services, and US$2,450 as salary per NEET beneficiary for a total of 100 days of guaranteed employment a year. The scope of employment under DESH can be estimated more realistically based on the present and projected need analyses of countries for SDG mandates and data from credible agencies, such as the ILO (2022) and the percentage realisation of SDGs (Figure 2) and various other country reports (Appendices). However, a preliminary appraisal of several such reports indicates the total NEET youth in G20 to fall within the lower and upper limits of 30 and 50 percent of the total number of post-secondary young people a year (Figure 2). Therefore, with a target of 100 million NEET youth over a five-year period under DESH, the yearly average outlay would amount to US$60 billion.

In addition to funding mobilisation through governmental and multilateral channels, the G20 can look at inviting private participation, such as introducing tax incentives to encourage businesses to support and hire youth in DESH for transitioning to decent employment and job security with dignity. Furthermore, countries can consider introducing grants and subsidies and allow corporate social responsibility funds to help young people start their own businesses during and after the completion of 100 job days by offering lucrative pathways for inviting more private capital in ventures of DESH participants.

Limitations. DESH must overcome three constraints—financial, political, and administrative. Some G20 countries may lack substantial financial resources. Most likely the political opposition to policy can be because of vested interests, or some may view it as a form of government intervention in the market. Furthermore, some G20 countries may lack the necessary infrastructure to effectively implement the policy.

Specific Recommendations

- G20 countries, along with multilateral agencies, should establish a five-year DESH fund as a pilot mission to ensure an outlay of US$60 billion a year to include a total of 100 million NEET beneficiaries in employment to deliver targeted productive assets under the respective country’s Shelf of Work for sustainable habitat outcomes.

- Individual G20 countries should engage with stakeholders, such as businesses, civil society organisations, and local communities, in order to build support for the policy.

- Strengthen the administrative and e-governance capacity from local government levels and upward to effectively implement the policy.

- Strategically build a country-wide Shelf of Work with continuous updates and fixation of outcome priorities against available Shelf of Work.

- Establish an effective monitoring and evaluation system of DESH that involves all stakeholders’ participation, from the local government unit upward.

- Install a robust technology system. There have been favourable G20 declarations since 2017 for digital transformation employing appropriate and modern technology systems (Table 1). However, there must be technology acceptance by DESH stakeholders as well as beneficiaries (Figure 3).

- The DESH Learning Management System (LMS), as an aggregator of relevant education and training credentials in blended modes, multiple language options, graphical interfaces, augmented and virtual reality for an immersive experience of habitats, satellite imaging, and geographical information, among other features, for mobile and self-paced learning, should be able to prepare demanding NEET youth for DESH employment.

- The induction of NEET youth necessarily has to comply with the requisite credentials from DESH LMS and comply with the associated eligibility and employment criteria.

- Overall, the DESH technology system, such as DESHSoft, should enable participating governments with just-in-time decision-making on the following: (a) priority works at local governmental levels; (b) education, training, and certifications; (c) local-to-wide area management of work and operations; (d) public-private and multilateral partnerships for resources mobilisation; (e) allocation and utilisation of funds; (f) critical assets development; (g) job days grants and absorption; (h) intra- and inter-governmental reporting and communications among other things, which would be essential to uphold the inclusive process in the enrolment of beneficiaries as well as to monitor and evaluate the quality of outputs and outcomes. It would also aid in stopping resource leakages, time delays, and cost overruns.

- Transition DESH beneficiaries to decent and secured income generation activities.

Recommended Country Practices for DESH. The G20 countries’ best practices (see Table 2) can be utilised by individual countries in the DESH system.

Table 2: Recommended Best Practices for DESH

| Relevant DESH Area | Countries | Source |

| Environmental performance | Germany, the United Kingdom, France, South Korea, and Japan | 2019 Environmental Performance Index |

| Rural infrastructure | Japan, Germany, France, the United Kingdom, and Canada | World Bank’s 2018 Rural Infrastructure Development Index |

| Urban infrastructure | The United States, Japan, Germany, the United Kingdom, and France | 2017 Global Urban Competitiveness Index |

| Renewable energy | China, the United States, Germany, India, and Japan | 2019 Renewable Energy Country Attractiveness Index |

| Waste management | Japan, South Korea, Germany, France, and the United Kingdom | 2018 World Waste Index |

| Clean and safe water and water management systems | France, Japan, the United Kingdom, Germany, and South Korea | 2018 Water Resources Performance Index |

Source: Authors’ own

Development of Social Enterprises. A social enterprise[c] can be any not-for-profit private activity for producing goods and services in public interest and with an entrepreneurial mindset for the fulfilment of strategic economic and social goals, thereby devising innovative solutions to the problems of social exclusion and unemployment. The above recommendations shall pave the way for the cultivation of social entrepreneurs and newer jobs. That gives a distinct entrepreneurial advantage to societies with younger populations in the 18-34 age group (Global Entrepreneurship Monitor 2023).

Finally, through DESH, the favourable deliberations held under previous G20 presidencies can be carried forward through an inclusive process to reap the demographic dividends with NEET youth in decent employment and entrepreneurship.

Appendix. Labour and Employment: G20 Overview

| Country | Document | URL |

| Germany | The German Labour Market in 2022, Federal Employment Agency | https://statistik.arbeitsagentur.de/DE/Statischer-Content/Service/English-Site/Generische-Publikationen/German-labour-market-2022.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=2 |

| France | 2017-2027. Boosting Employment in France, France Strategie | https://www.strategie.gouv.fr/sites/strategie.gouv.fr/files/atoms/files/17-27_boosting_employment.pdf |

| UK | Plan for Jobs, HM Government | https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1016764/Plan_for_Jobs_FINAL.pdf |

| Japan | Shinya Kotera and Jochen M Schmittmann, “The Japanese Labor Market During the COVID-19 Pandemic,” International Monetary Fund, 2022. | https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WP/Issues/2022/05/13/The-Japanese-Labor-Market-During-the-COVID-19-Pandemic-517840 |

| Asia and Pacific Department, “Japan Economic Outlook and Policy Priorities” June 9, 2022. | https://www.imf.org/-/media/Files/OAP/oap-home/2022/imf-asia-pacific-regional-seminar-on-japan-2022-june.ashx | |

| Italy | Arianna Tassinari, “Labour Market Policy in Italy’s Recovery and Resilience Plan. Same Old or a New Departure?” Contemporary Italian Politics 14, no. 4 (2022): 441-457, doi: 10.1080/23248823.2022.2127647 | https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/23248823.2022.2127647?scroll=top&needAccess=true&role=tab |

| Republic of Korea | Byung-Suk Chung, “Reforms of the Employment Insurance System of the Republic of Korea to Cope with the COVID-19 Crisis,” International Labour Organization, 2021. | https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—asia/—ro-bangkok/—ilo-jakarta/documents/publication/wcms_829877.pdf |

| Canada | Tiff Macklem, “Restoring Labour Market Balance and

Price Stability,” Public Policy Forum, November 10, 2022. |

https://www.bis.org/review/r221111e.pdf |

| Australia | Australian Council of Social Service, “Restoring Full Employment: Policies for the Jobs and Skills Summit,” 2022. | https://www.acoss.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/ACOSS_Restoring-full-employment_Policies-for-the-Jobs-and-Skills-Summit_2022.pdf |

| USA | Economic Report of the President, White House, 2023. | https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/ERP-2023.pdf |

| Russia | International Labour Organization, “Employment and Labour Market Strategies in Russia in the Context of Innovations Economy,” 2012. | https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—europe/—ro-geneva/—sro-moscow/documents/publication/wcms_306607.pdf |

| Turkiye | Youth Deal Cooperative / Genç İşi Kooperatif, “Youth Employment in Turkey: Structural Challenges and Impact of the Pandemic on Turkish and Syrian Youth,” International Labour Organization, 2022. | https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—europe/—ro-geneva/—ilo-ankara/documents/publication/wcms_849561.pdf |

| Saudi Arabia | Harvard Kennedy School, “The Labor Market in Saudi Arabia: Background, Areas of Progress, & Insights for the Future,” 2019. | https://epod.cid.harvard.edu/sites/default/files/2019-08/EPD_Report_Digital.pdf |

| Brazil | Abdulelah Alrasheedy, “The Cost of Unemployment in Saudi Arabia,” International Journal of Economics and Finance 11 (2019): 30, 10.5539/ijef.v11n11p30. | https://www.researchgate.net/publication/336433983_ The Cost_of_Unemployment_in_Saudi_Arabia |

| Rodrigo Martins Soares, “Reducing the Youth Unemployment in Brazil: A Practical Approach,” ILO, 2020. | https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—dgreports/—inst/documents/publication/wcms_776390.pdf | |

| Argentina | National Directorate for Economy, Equality & Gender and UNICEF. “Public Policy Changes in Light of the Care Crisis,” May 2021. | https://www.argentina.gob.ar/sites/default/files/2022/09/care_crisis_public_policy_challenges.pdf |

| China | World Bank, “Navigating Uncertainity-China’s Economy in 2023,” 2022. | https://thedocs.worldbank.org/en/doc/b8644c8a79ee3376b2cd3c16a9f90cc7-0070012022/original/CEU-December-2022-ENG.pdf |

| Mexico

|

Gabriela Siller Pagaza et al., “Mexico’s Economic Outlook,” Grupo Financiero Base, 2022. | https://www.bancobase.com/sites/default/files/2023-01/Mexico%20Economic%20Outlook%202022%20Q4.pdf |

| South Africa | Lorainne Ferreira, “South Africa’s Economic Policies on Unemployment: A Historical Analysis of Two Decades of Transition,” Journal of Economic and Financial Sciences 9 (2016): 807-832, 10.4102/jef.v9i3.72. | https://www.researchgate.net/publication/317143804_South_Africa’s_economic_policies_on_unemployment_A_historical_analysis_of_two_decades_of_transition |

| Indonesia | MCPS for the Republic of Indonesia (2022-2025), “Supporting Economic Transformation & Inclusive Human Capital Development for Indonesians,” July 2022. | https://www.isdb.org/sites/default/files/media/documents/2022-07/Indonesia%20MCPS_Final_Printing%20Version_MCPS%20Launch%20Event_compressed.pdf |

| India | “Labour & Employment Statistics,” Government of India, 2022. | https://dge.gov.in/dge/sites/default/files/2022-08/Labour_and_Employment_Statistics_2022_2com.pdf |

Attribution: Krishnendu Sarkar et al., “Development and Entrepreneurship for Sustainable Habitats,” T20 Policy Brief, June 2023.

References

“The World’s Most Entrepreneurial Countries 2021.” CEO World Magazine. ceoworld.biz/2021/01/03/worlds-most-entrepreneurial-countries-2021/.

Global Entrepreneurship Monitor 2022/2023 Global Report: Adapting to a “New Normal”. GEM. gemconsortium.org/report/20222023-global-entrepreneurship-monitor-global-report-adapting-to-a-new-normal-2.

Global Entrepreneurship and Development Institute. “2018 Global Entrepreneurship Index Ranking.” thegedi.org/global-entrepreneurship-and-development-index/.

ILO. “World Employment and Social Outlook 2022.” ilo.org/global/research/global-reports/weso/trends2022/lang–en/index.htm.

ILO. “Global Employment Trends for Youth 2022. Investing in Transforming Futures for Young People”.

IMF. Global Finance Stability Report. 2023. imf.org/en/Publications/GFSR.

OECD. “Unemployment Rate.” data.oecd.org/unemp/unemployment-rate.htm.

Petrucci, A.L., and N. Trasi. “Involving Higher Education (SDG 4) in Achieving Sustainable Cities and Communities (SDG 11) through Problem-Solving and Learning-by-Doing Practices Towards the 2030 Agenda.” G20 Italy. 2021. t20italy.org/2021/09/21/involving-higher-education-sdg4-in-achieving-sustainable-cities-and-communities-sdg11-through-problem-solving-and-learning-by-doing-practices-towards-the-2030-agenda/.

Sarkar, K. “A Sustainable Model of Social Bonding for Development of Tourism Destinations: Prospecting a Case for the Indian Himalayan Region.” 2022. DOI:10.18843/rwjasc/v13i1/02.

United Nations, “The 17 Goals.” sdgs.un.org/goals.

United Nations. Sustainable Development Report 2022. dashboards.sdgindex.org

United Nations. UN-Habitat. unhabitat.org.

UNDESA. Public-Private Partnerships and the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development: Fit for Purpose? 2016. sdgs.un.org/publications/public-private-partnerships-and-2030-agenda-sustainable-development-fit-purpose-18018.

University of Toronto. “G20 Research Group.” www.g20.utoronto.ca/.

WEF. The Future of Jobs Report. October 2020. www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Future_of_Jobs_2020.pdf.

World Bank. “New World Bank Country Classifications by Income Level: 2022-23.” blogs.worldbank.org.

World Bank. “World Bank 2020 Data on the Unemployment Rate.” data.worldbank.org.

[a] Details available in WEF, “The Future of Jobs Report 2020”. The Addis Ababa Agenda for Action (AAAA) highlights the importance of a holistic approach and circular economy management for the recipients of public funds, including public-private partnerships (https://sdgs.un.org/publications/public-private-partnerships-and-2030-agenda-sustainable-development-fit-purpose-18018). Furthermore, the inclusion of different categories of the beneficiary within the same project, at different levels of education and/or professional experience can build consistent human capital in developing countries. This Policy Brief aims to target SDG-6: Clean water and sanitation; SDG-7: Affordable and modern energy; SDG-8: Decent work; SDG-11: Sustainable cities and communities; SDG-12: Responsible consumption and production; SDG-13: Climate action; SDG-14/15: Conservation of land and marine diversity; and SDG-17: Partnerships (https://www.un.org), and UN-Habitat (unhabitat.org).

[b] Supported by the University of Toronto’s G20 Research Group, which provides insightful information pertaining to meetings and declarations.

[c] According to the OECD and the European Commission’s definitions of social enterprise