Task Force 1 Macroeconomics, Trade, and Livelihoods: Policy Coherence and International Coordination

Abstract

The G20 has promoted trade and cross-border investments since its inception. To improve the trade environment within the grouping’s diverse member countries, there is a need to address the higher costs incurred by the various trading communities by encouraging the use of data-driven digital trade measures. Certain common challenges must be redressed, including compliance issues, enabling hard and soft infrastructure, using automated technologies for behind-the-border facilities and procedures, and using advanced trading and logistical applications.

This policy brief proposes a strategic trade facilitation framework to help medium and small exporters engage more meaningfully in trade by becoming more competitive in international markets. The framework adopts a holistic approach, whereby trade facilitation is concentrated on the time, cost, and reliability of processing trade movements on behalf of stakeholders.

The Challenge

The benefits of international trade are better realised when goods and services are delivered to customers within the committed time and at a competitive price. High trade costs, delayed product delivery, and in-transit product damages lead to distorted prices, expiry of products, consumer dissatisfaction, unfair market competition, and a decline in international trade revenues and welfare gains.

Many trade facilitation initiatives have already been undertaken at different levels—some initiatives are under the Ease of Doing Business platform at the domestic levels, others are under free trade agreements, including at the regional or multilateral level. World Trade Organization (WTO) estimates show that trade costs may decline by 14.3 percent and global trade may increase by US$1 trillion per year with the full implementation of the multilateral Trade Facilitation Agreement (TFA).[1] A key challenge is that the G20 member states are at differing stages in ratifying and implementing the TFA’s measures. Progress on the TFA is slow, with some measures expected to be fully adopted only by 2050. For faster implementation, there is a need to introduce a TFA+ framework with more focus on automation and digitalisation.

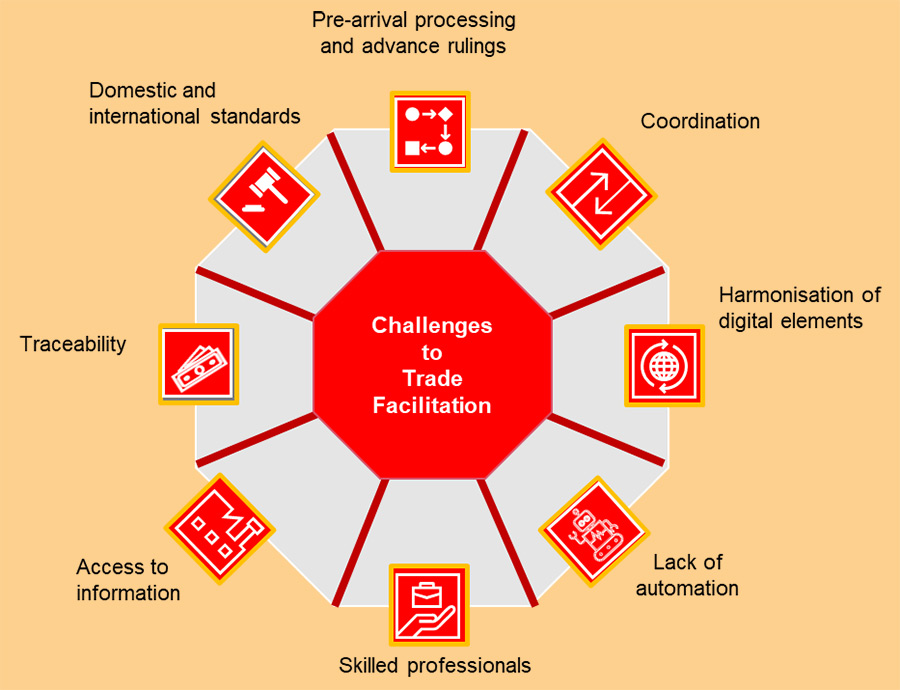

Some trade facilitation challenges are common across countries, while others are limited to a region, stage of development, or trade architecture. This policy brief identifies the challenges to trade facilitation[a] in the G20 countries (see Figure 1) and proposes recommendations to establish a digitally-enabled framework that can eventually reduce time delays and trade costs.

Figure 1: Challenges of trade facilitation in the G20 countries

Source: Authors’ analysis

Limited focus on harmonising digital elements in regional trade agreements

There is a limited focus on digitalising the trade process at the multilateral, bilateral, and regional levels. There is no mention of digital trade in the TFA, and very few regional trade agreements (RTAs) have a chapter or section on digital trade. As per the Trade Agreements Provisions on Electronic Commerce and Data, of the 239 RTAs in which at least one of the G20 countries is a party, only 88 contain a digital trade element and only 65 have an electronic transactions framework.[2] RTAs are great enabling platforms for trade facilitation measures, but in the case of G20 members, there are very few bilateral or multilateral RTAs where it has achieved some success.

The implementation of trade facilitation-related agreements require collaboration between customs administrations, customs brokers, and other stakeholders. Some of the challenges in the implementation of digitalisation in customs include the lack of know-how, insufficient management support, insufficient network, and lack of access to technologies. The G20 member countries’ integration in different RTAs are highlighted in Figure 2.

Figure 2: The G20’s integration through regional trade agreements* (as of 17 March 2023)

Source: Authors’ analysis based on the WTO’s Regional Trade Agreements Database

Note: Regional Trade Agreements include Free Trade Agreements, Customs Union, Economic Integration Agreement, Partial Scope Agreement

Non-alignment of domestic and international standards

Standardisation is a key pillar of trade facilitation. The alignment of domestic and international standards for documents, certificates, formalities, product codes, data, and information are very important for smooth trade. Under Article 10.3, the TFA encourages members to use international standards as a basis for trade-related formalities and procedures. It also encourages members to participate and contribute to the preparation and periodic review of international standards, which is mainly undertaken by international organisations. However, as per the TFA database, the full implementation of this measure is projected to be completed by 2040.[3] According to the UN Global Survey on Digital and Sustainable Trade Facilitation-2021, less than half of all G20 members have fully implemented the measure for ‘national standards and accreditation bodies to facilitate compliance with Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures’.[4]

· Easy access to information and coordination

Accurate and timely information is a prerequisite for companies to decide about sales contract, procurement, production, export, import, and international marketing. With the introduction of a wide range of compliances and the differentiated treatment of items at the customs points (based on their country of origin, type of consignment, and mode of transport), easy access to information is even more important. For example, in many countries, tariff rates change frequently, impacting the overall trade cost and creating a risk of uncertainty among traders.

The TFA’s ‘information availability’ measure covers enquiry points and the publication of trade related information, including on the Internet. Article 1 of the TFA elaborates on the ‘publication and availability of information’, providing a list of information that a TFA member should promptly publish in a manner that it is easily accessible to all without discrimination. The full implementation of these measures is not expected before 2035.

Besides information availability, there is a need for strong coordination among the border agencies, and between customs, businesses, and other related domestic and international authorities. While the TFA addresses the issue of border agency cooperation,[5] only 62.3 percent of WTO countries have implemented this provision (as of 17 March 2023), and full implementation is only expected by 2040.[6]

· Traceability

Traceability or product tracing is defined as “the ability to follow the movement of an item through specified stage(s) of production, processing and distribution.”[7] Traceability is used as a measure to control hazards, record and share product information, and authenticate a product’s lifecycle.[8] It is a key factor of trade and supply chains, especially for food items, but will continue to become more important with the adoption of sustainable practices across global value chains. The TFA does not include traceability in its list of measures.

Participants in modern supply chains expect to have complete information of a product that will allows for quick identification, location, and withdrawal of a product during a suspected or confirmed problem. This requires the adoption of measures that enable stakeholders to easily track and trace a product in the entire supply chain.[9]

· Lack of skilled professionals

Many ports, and border and customs points face the problem of a lack of skilled professionals who can undertake the process in an efficient and risk-free manner. According to a World Customs Organization report, there are several issues related to compliances and integrity of brokers. The presence of informal brokers who operate without a license is not only unfavourable to professional brokers and traders, but it also raises concerns from the compliance point of view. As per the study, 42 members (or 47 percent of respondents) cited this as a problem area, with 13 members (15 percent of respondents) terming it a very serious problem.[10]

· Lack of automation

Automation is one of the most important parameters of trade facilitation and cuts across almost all of the trade facilitation measures. It saves both time and cost, makes the customs process much faster and smoother, and provides transparency. Although it was envisaged to be implemented by 2020, imports and exports remain largely governed by a mass of physical paper.[11]

The Trade Facilitation Index (TFI) includes automation in its list of evaluation parameters. G20 countries’ average score on this parameter stands at 1.7 (on a scale of 0 to 2), with some G20 countries having a very low score.[12] A key challenge related to automation as a trade facilitation practice is the duplication of process through the automated system and manual paperwork.

· Lack of pre-arrival processing and advance rulings

The pre-arrival processing of documents and information, and advance rulings saves time and cost in transit, and protects traders from a sudden change of rules that could result in consignment rejection, delayed delivery, or unexpected additional documentation and charges. As per Article 7.1 of the TFA, each member is required to submit the required documents in the electronic format for pre-arrival processing so that arrivals can be expedited.[13] However, as per the TFI, the G20 countries have an average score of 1.8 on a scale of 0 to 2 for the measure. The best practice set by the TFI is 1.9, which indicates that there is a scope for improvement on this front.[14] As per the TFA database, the implementation of this measure is expected to be completed by 2040.[15]

· Issues related to risk management system

Even if the customs clearance is carried out in an effective manner, the relative inefficiency of the clearances related to participating government agencies (PGAs) causes delays and increases transaction costs. This calls for a strong risk management system (RMS). However, the RMS cannot be limited to customs alone; PGAs should have their own RMS and a digital system for capturing data relevant to their specific risk factors to make trade facilitation more effective.

Many countries’ PGAs fall short of standards because of their inability to utilise a comprehensive set of risk factors and suitable risk principles. The PGAs do not have relevant data for identifying risks as they do not manage a digital database and do not have a sophisticated digital clearance system.

The G20’s Role

The G20 had committed to ratifying the TFA by the end of 2016 and called on all WTO members to do the same. The G20 has been committed to support a rules-based and inclusive multilateral trading system, and has proved its determination to play its role in lowering global trade costs. The G20 also supports mechanisms such as ‘aid for trade’ and providing capacity building assistance to developing countries. [16]

The G20 is seen as a trend-setting bloc at the WTO. According to the 28th WTO Trade Monitoring Report on G20 trade measures, during May-October 2022, G20 economies introduced more trade-facilitating (66) than trade-restrictive (47) measures on goods (these numbers exclude measures related to the pandemic).[17] Based on the report, the G20 countries were called on to refrain from adopting new trade-restrictive measures and to promote multilateral trade enhance a positive global economic outlook.

The G20 countries represent 80 percent of global trade, and most member countries are at a comparatively advanced stage of development and technology usage. A robust G20-specific trade facilitation framework that utilises global best practices and uses digital tools will help the member countries and those that trade with the G20. The framework can thus also be proposed at global platforms such as the WTO and World Customs Organization for wider utilisation.

Some of the G20 countries perform well in trade facilitation and their best practices may be leveraged by other countries for the overall improvement of global trade facilitation performance. According to TFI, South Korea ranks first with a score of 1.87, followed by the Netherlands (1.87), Japan (1.85), the US and Sweden (both at 1.84) on a scale of 0 to 2.[18] The G20 countries perform well in the areas of advance rulings, fees and charges, and governance and impartiality.[19] Similarly, many of the G20 countries are among the best performers in the global indices like Average Trade Cost Index[20] and Logistics Performance Index.[21]

Recommendations to the G20

· A TFA+ framework

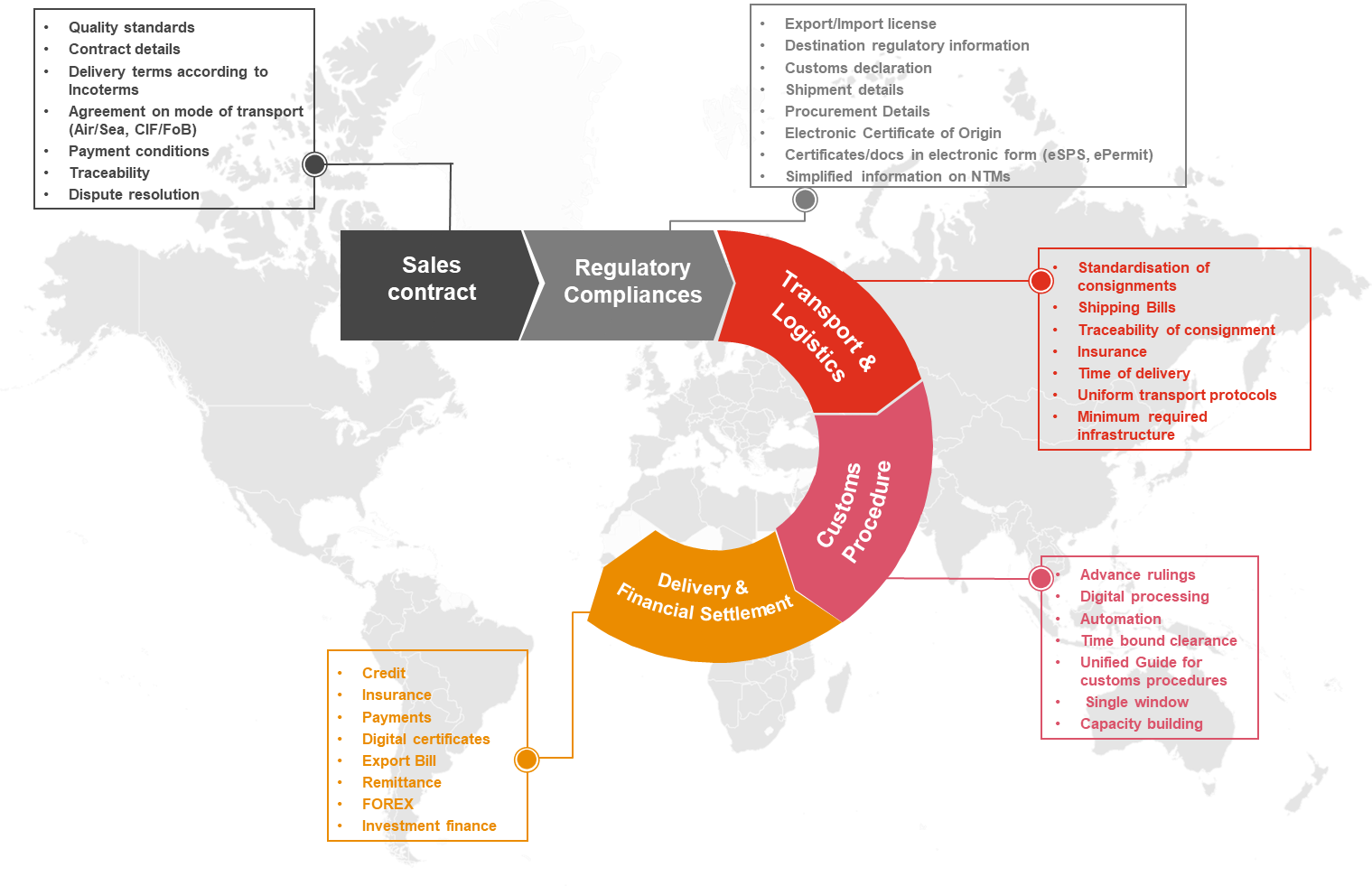

There is a need for a TFA+ framework that would cover every aspect of the trade lifecycle, from when two parties enter a discussion on a contract until the product is delivered and payments are settled. The framework will guide traders in the entire trading process— sales contracts, regulatory compliances, transport formalities, customs clearance and procedures related to credit, finance, and transactions. Digital transformation and adaptability are required to achieve effective integration in global supply chains, and a TFA+ approach will be helpful in achieving this. The COVID-19 pandemic has spurred trade processes to shift to digital practices. Digital practices are being undertaken at every step of the export/import lifecycle (see Figure 3). A TFA+ approach will help to push trade facilitation by bringing in a digital cross-border trading system, which will also help countries negotiate their RTAs. Some countries have already included the digital aspect in their foreign trade policy. For example, India’s new foreign trade policy[22] focuses on reducing trade costs through the implementation of integrated digital initiatives that would simplify trade facilitation processes and reduce processing time and costs.

Figure 3: The export/import lifecycle

Source: Authors’ own analysis

· Standardised information and codes in international trade data exchange

Data that shares the same identification may have distinct meanings based on the parties using it and, as a result, the context of the exchange might become ambiguous. When more and more data transmission mechanisms are developed, it becomes important to ensure that the information is understood in the same way.

Benefits

- Ensures identical comprehension of data by all parties

- Saves time, cost, and effort needed for data mapping

- Enables software developers and implementers to build the right data sets

- Eliminates the need for bilateral negotiations and agreements to define each business case

Action Points

- The G20 countries can ensure that all public- and private-sector supply chain participants consider standardised data for electronic data exchange, maintain a transparent record, give codified data precedence over textual inputs, and use openly-accessible international code lists

- The G20 can form a committee of experts to identify gaps between its members’ standards and international standards and recommend changes to align them

For instance, Singapore’s public and private sectors came together to create the Singapore Trade Data Exchange, a public digital infrastructure that facilitates trusted and secure data sharing and aims to allow data connections for a wide range of data contributors and data users.

· Single submission portals

A single submission portal (SSP) is a common access point that enables all trade stakeholders to share information in a standardised manner for an activity related to trade. SSPs cover information required for enabling business-to-business activities (such as dealing with transport, logistics and financial services), and facilitate regulatory processes through information exchanges between businesses and a government.

Benefits

- Easier clearance

- Better financial and regulatory support

- Saves time, cost, and efforts of different private and government agencies

Action Points

- The G20 members can consider implementing an SSP by making provisions for a legally enabling environment for these facilities

- The G20 members can explore interoperability options that would help until the SSP is completely implemented.

For instance, by bringing together trade and transport stakeholders (such as customs brokers, freight forwarders, logistics companies, warehouses, export agencies, banks, and insurance companies), the Integrated Services for MSMEs in International Trade platform aims to offer small and medium enterprises professional international trade services. Another example is the ASEAN Single Window, a regional electronic platform to promote economic integration and connectivity through the expedited electronic exchanges of trade-related documents among ASEAN member states.

· Trade information portals

A trade information portal (TIP) is an online facility that compiles and makes all regulatory and procedural information related to trade available through a user-friendly Internet site. It enables easy access to searchable, precise, thorough, and up-to-date information at a single source. It makes it easier for the private sector to access, comprehend, and abide by trade agreements and laws.

Benefits

- Provides easily accessible information necessary for traders to plan their processes and resources for cross-border operations

- Supports cross-agency cooperation. Agencies can align their requirements and standards by using the information provided on the portal.

Action Points

The G20 members can establish a TIP to improve the dependability, transparency, and predictability of trade information. It must appoint a collaborative governance body with all key stakeholders for strategic direction and oversight of the creation, implementation, and functioning of the TIP. The G20 countries can have a common TIP, and must be responsible for the information relation to their jurisdiction.

· Integration of new technologies in risk management

It is nearly impossible to examine and inspect each shipment that crosses international borders. This calls for the development of a robust RMS. Technologies like artificial intelligence can be utilised in the customs clearance system as it has the capability to manage risks efficiently with minimum error.

Benefits

- Increased efficiency, transparency, and predictability of customs clearances

- An RMS also aids in the strategic and efficient assignment of personnel

Action Points

- The G20 can mediate prompting improvement and procedural efficiency through the digitalisation of procedures. The following elements can be developed for an advanced RMS:

- a digital framework for gathering comprehensive and relevant information about the risk factors, in addition to what is contained in the customs declaration

- a database for risk management-related historical data

- a method for thoroughly defining the risk principles and an IT solution (i.e., artificial intelligence, machine learning solutions) for applying those principles

For instance, the UK’s Food Standards Agency (FSA) has developed an early warning system and smart surveillance by analysing data from different sources, including Trade Control and Expert System, Rapid Alert System for Food and Feed, and the Procedure for Electronic Application for Certificates. This includes looking at the degree of risk or any safeguards that are associated with the products, the history of the importer, previous records of measures taken against the country of origin, and other factors. The FSA analyses (open) data using data science methods to identify emerging risks before they become a threat to public health. For instance, the FSA uses data on global climate change to estimate crop patterns and disease outbreaks.

· Effective implementation of trade and transport facilitation monitoring mechanism

To understand and improve different facets related to trade facilitation, the G20 countries may set up sustainable trade and transport facilitation monitoring mechanisms (TTFMMs) to and evaluate the development of trade and transportation facilitation.

Benefits

- Cost-effective and sustainable monitoring of trade and transport facilitation

- Accurate, structured, consistent, and harmonised data available for modernisation and policymaking

- Improved capacity of human resources for trade and transport facilitation

- Simplified trade and transport processes, enhanced trade efficiency, and increased trade competitiveness.

Action Points

- The G20 can encourage the implementation of TTFMMs under the supervision of national trade facilitation bodies, and then establish a G20 bloc-level mechanism.

- Member countries can gather information on trade and transportation facilitation for effective monitoring

Some existing automated systems, such as the Automated System for Customs Data, may be used to collect data. However, there are certain issues, including the absence of provisions to accept e-documentation and e-payments, that needs to be resolved on priority.

· Improving transparency and traceability of sustainable value chains

There is a growing demand for policy actions to promote ethical business practices by improving transparency and traceability in global value chains.

Benefits

Such an effort will help to find authenticated sustainability claims and make it cost-efficient by simplifying and improving organisational processes, particularly for small and medium enterprises. It will also make the sustainability claims reliable in areas such as human rights and environment.

Action Points

- The G20 members can define the minimum required data and level of traceability for different value chains in support of sustainability claims

- To ensure circularity in the value chains, there is a need to harmonise policies that would help to achieve higher environmental and social standards.

- Encourage businesses to adopt greater transparency in the operations of the value chain, and provide financial and non-monetary incentives for the same.

The ‘Blockchain for Made in Italy Traceability’ pilot project aims to evaluate the use of blockchain technology in the implementation of traceability. Similarly, the UNECE blockchain traceability pilot project for organically-farmed Egyptian cotton aims to demonstrate the potential use of blockchain technology with the objective of increasing connectivity and cost-efficiency. However, to use blockchain technology, data and its exchange across countries requires standardisation. Moreover, the absence of interoperability creates compatibility problems as different types of traceability techniques are used by several actors in the entire supply chain.

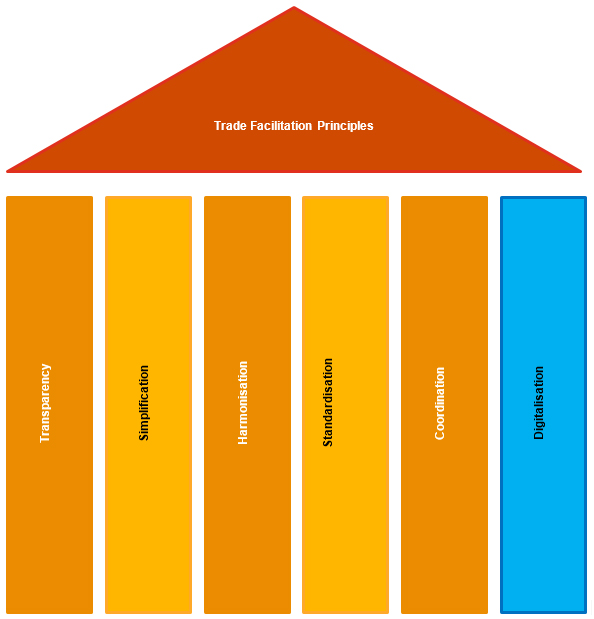

· Including ‘digitalisation’ as a sixth pillar of trade facilitation

The trade facilitation system was originally built on four pillars—transparency, simplification, harmonisation, and standardisation. A fifth pillar, ‘coordination’, was added to the trade facilitation system by the WTO in 2017. Considering the role and potential of modern technologies in addressing the challenges and improving trade facilitation, it is recommended to include digitalisation as a sixth pillar in the G20 digital trade facilitation strategic framework (see Figures 4 and 5).

Figure 4: The G20 Trade Facilitation Framework

Source: Authors’ own

The sixth pillar will involve the latest technologies—this may include digital skills training, facilitating information access, and the submission of appropriate information. By focusing on digitalisation as a solution to most challenges faced by exporters in the G20 member countries, the framework strives to integrate modern technologies into the trade process systems to make it simpler, transparent, standardised, harmonised, and factual. The digitalisation of the trade facilitation system will help parties within and among countries to coordinate better.

Figure 5: Defining the G20 Trade Facilitation Framework

The framework provides a lot of focus on infrastructure development, making it compatible with the digital systems in terms of hard infrastructure and soft infrastructure, and addresses the skill gaps through building capacity of digitally-enabled human resources.

[a] Based on the five principles of trade facilitation—transparency, simplification, harmonisation, standardisation, and coordination—as mandated by the WTO.

[1] “Trade Facilitation,” World Trade Organisation, accessed April 10, 2023.

[2] “TAPED,” University of Lucerne, accessed March 20, 2023.

[3] “Trade Facilitation Agreement Database,” World Trade Organisation, accessed on April 10, 2023.

[4] “UN Global Survey on Digital and Sustainable Trade Facilitation,” United Nations, accessed April 12, 2023.

[5] “Customs Cooperation,” World Trade Organisation, accessed March 25, 2023.

[6] “Implementation progress by measure,” World Trade Organisation, accessed April 30, 2023.

[7] “Codex Alimentarius Commission (CAC),” Food and Agriculture Organisation of India, accessed April 14, 2023.

[8] “Food Safety and Quality,” Food and Agriculture Organisation of India, accessed April 14, 2023.

[9] “Food Safety and Quality”

[10] “WCO Study Report on Customs Brokers,” World Customs Organisation, accessed March 16, 2023.

[11] “Tackling the Big Customs Skills Shortage,” EU Business News, Last modified September 2, 2021.

[12] “Trade Facilitation Indicators 2022 edition,” OECD, accessed March 15, 2023.

[13] “Trade Facilitation Indicators 2022 edition”

[14] “Trade Facilitation Indicators 2022 edition”

[15] “Trade Facilitation Indicators 2022 edition”

[16]“G20 Action Plan on the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development,” G20 Germany, accessed April 12, 2023.

[17] “WTO report shows G20 trade restrictions increasing amidst economic challenges,” World Trade Organisation, last modified November 14, 2022.

[18] “Trade Facilitation Indicators 2022 edition,” OECD, accessed March 15, 2023.

[19] “Trade Facilitation Indicators 2022 edition”

[20] “Trade Cost Index,” World Trade Organisation, accessed March 10, 2023.

[21] “Logistics Performance Index,” World Bank, accessed March 10, 2023.

[22] “Foreign Trade Policy 2023,” DGFT, accessed April 13, 2023.