Task Force 5: Purpose & Performance: Reassessing the Global Financial Order

‘Green financing’ is a structural financial activity that seeks to improve environmental outcomes of projects. It can be in the form of loans, debt mechanisms or investments that are channelled to those projects which limit carbon emissions into the economy (mitigation) or minimise the negative impacts of existing projects (adaptation). One such emerging green financing tool is ‘green bonds.’ Green bonds represent, by far, the largest and most mature segment of the sustainable debt market. This Policy Brief provides a summary of the global green bonds market, and discusses the role that G20 economies can play in improving it. It suggests measures to mitigate the risks associated with green financing and scale up the green bonds market across the G20 economies.

1. The Challenge

In 2009, at the Conference of the Parties (COP) 15 in Copenhagen, nations agreed to bring down the global temperature by significantly reducing carbon emissions and addressing climate change. Tackling the challenges and risks associated with climate change presents an investment opportunity. It is encouraging that there has been a significant increase in investment related to climate resilience financing, especially in developing economies. A robust nexus between the private and public sectors can unlock new investment opportunities, reduce the cost of capital, and mobilise the necessary financing on a larger scale.

One mechanism by which private finance can complement public sector financing is bond financing. Bond financing is a natural fit for climate infrastructure projects. Governments around the world are resorting to municipal bonds to finance infrastructure; these have become an important financial innovation in sustainable finance. The difference between green bonds and other ‘vanilla’ bonds is the ‘use of proceeds’ clause in the former, which specifies that the proceeds need to be used to finance only clean and green infrastructure such as electric transportation and renewable energy.

The green bonds market comes with its challenges. Infrastructure financing includes manifold risks such as uncertainty of the tenure of the project, and lower returns than other comparable financial assets. For green bonds in particular, the lack of transparency with regard to usage of the proceeds, coupled with greenwashing, creates an additional barrier for adoption and scaling up.

The market for green bonds

A green bond is a fixed-income debt instrument, wherein the proceeds of the bond are used strictly to finance or refinance sustainable and green projects. These bonds attract socially responsible investors. The World Bank, in cooperation with the Swedish bank SEB, issued the first green bond in 2008,[1] and the demand for green bonds has been on the rise since then. Globally, issuance of green bonds crossed the half-trillion mark in 2021, with Europe the largest issuer.[2] In 2021, the United States was the biggest individual issuer of green bonds, amounting to US$81.9 billion. Among emerging market and developing economies, China led with US$59 billion, followed by India with approximately US$6 billion.[3]

Green bonds are considered effective financing instruments for climate action. Bonds with a thematic label totalled US$3.5 trillion in September 2022, with green bonds representing the largest portion (64 percent).[4] Globally, issuers sold US$443.72 billion worth of green bonds in 2022, down from US$596.30 billion in 2021, according to data from the Climate Bonds Initiative.[5] This decline was partially due to economic uncertainty, compounded by the interest rate hikes of the US Federal Reserve. As of 2021, green corporate bonds accounted for nearly 6 percent of global corporate bonds outstanding, up from less than 1 percent in 2014 (Carmichael and Rapp, 2022).

Green bonds are a subset of sustainable bonds and come under the umbrella of Green, Social and Sustainable (GSS) Bonds. The Green Bond Principle (GBP) provides a set of voluntary process guidelines that support issuers. Green bonds are issued by sovereign entities, sub-sovereign entities or supranational entities (such as multinational development banks).

Table 1: Types of Green Bonds

| Type of Bonds | Description |

| Sovereign Bonds | Bonds issued by a sovereign government |

| Project Bonds | Bonds backed by a single or multiple projects bearing project risk |

| Asset Backed Securities | Collateralised by one or more projects that usually provide lean on assets |

| Municipal Bonds | Bonds issued by a municipal government, region or city |

| Financial Sector Bonds | Corporate bonds that are raised by financial institutions with the sole objective of obtaining capital. |

| Corporate Bonds | A “use of proceeds” bond issued by a corporate entity with recourse to the issuer in case of default on interest payments or on return of principal |

Source: Author’s own, compiled from the World Bank database

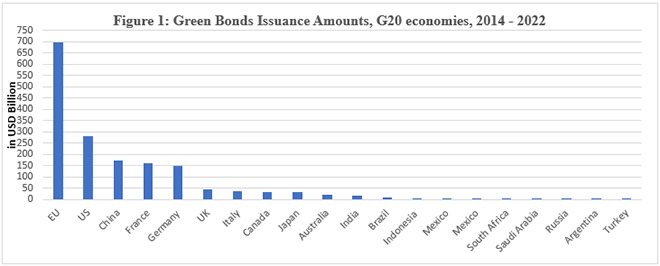

The first sovereign green bonds were issued by Poland and France as recently as in early 2017.[6] At the end of 2019, the share of sovereign issuers in total outstanding GSS bonds was 4.2 percent, increasing to 7.5 percent by end-June 2022.[7] Thus, green sovereign bonds have been growing steadily over the last few years. Globally, the United States has issued the most, totalling US$282.2 billion, followed by China with US$172.5 billion and France with US$159.8 billion. Germany comes fourth with US$148.5 billion (Figure 1).[a]

Source: Author’s own, using data from Climate Bonds Initiative

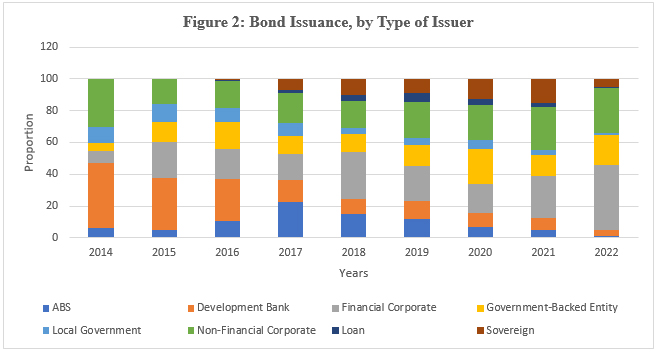

Among entities issuing green bonds, the share of development banks has reduced from 40 percent in 2014 to under 4 percent in 2022. Meanwhile, that of financial corporates has increased from 7 percent in 2014 to 40 percent in 2022. The proportion issued by non-financial corporates has remained constant at around 30 percent (Figure 2).

Source: Author’s own, using data from Climate Bonds Initiative

Challenges associated with green bonds

Green bonds are effective in targeted financing for climate change initiatives. However, they come with their own set of challenges. Some of them are listed below:

First, green bonds are customarily structured to align with the Green Bond Principles published by the International Capital Markets Association (ICMA).[8] However, since the alignment with the principles is voluntary, corporations may not always use the proceeds of the bonds for green projects. This is called greenwashing, a term coined by environmentalist Jay Westerveld in 1986, to denote corporate propensity to make extravagant claims of caring for the environment while in fact contributing to its degradation. Proceeds from green bonds are sometimes channelled towards projects or activities having negligible or negative environmental benefits. The rapid expansion of green bond issues could make both investors and regulators sceptical about them, fearing greenwashing. Instances of greenwashing could discourage potential investors from investing. It is the joint responsibility of the government, bond issuers, and independent rating agencies to check against greenwashing in the green bonds market. A coordinated effort among all stakeholders is needed; regulatory bodies should also provide stricter guidelines to maintain transparency in the use of green bonds’ proceeds.

Greenwashing can be tackled in many ways. Impact reports can be sought, which measure the ‘impact’ of the proceeds of a thematic bond. However, while increased expenditure on a particular green project is easily verified, its impact—positive or otherwise—can only be gauged by on-ground testing. Even so, providing impact reports could be a way for companies to differentiate themselves in the eyes of investors. Governments could also stipulate tax cuts/subsidies for green bond issuers who provide impact reports. Further, regulatory frameworks can reduce greenwashing. In February 2023, for instance, in India, the Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI) announced regulations related to green debt securities aimed at preventing greenwashing.[9] So too, did the United Kingdom’s Competition and Market Authority (CMA) publish a Green Claims Code to check greenwashing.[10] Enforcing the ICMA’s principles can help solve the problem of greenwashing.

Second, the transaction costs associated with issuing green bonds are relatively high. They include obtaining ‘green level certification’ from an independent agency and the need to provide documents detailing the use of green bond proceeds throughout a project’s life cycle. These costs can be as high as US$100,000.[11] Costs escalate from issuers having to track, monitor, and report the use of proceeds.

Third, awareness of green bonds is very low. The key to green bonds market development is to increase awareness of its benefits. Promotional efforts should be arranged by regulators, financial institutions and governments to educate the broader public.

Fourth, the World Bank has estimated that low- and middle-income countries will need investments of US$1.5-2.7 trillion per year (4.5–8.2 percent of their combined gross domestic product (GDP)) between 2015 and 2030 to meet their infrastructure related sustainable development goals (SDGs), depending on policy choices (Rozenberg and Fay 2019).[12] With the onset of the pandemic, followed by the economic downturn, developing economies are left with scarce financial resources to do so. It is imperative that the private sector also mobilises financing for green infrastructure projects; the public sector may not have the resources to fill the financing gap. However, it has been pointed out that, given the associated risks, private sector incentives do not align with the tenure of green projects, which are very long-term, with low interest rates (Yoshino and Taghizadeh-Hesary 2018).

Fifth, there is scepticism about green bonds because of their extensive ‘self-labelling’. At the start, when the initial bonds were issued by multilateral development banks or highly trusted entities, this was acceptable. However, with the rampant increase in green bonds, appointing an external review mechanism to assess them has become necessary. External reviews can be either pre-issuance or post-issuance. Pre-issuance review can be through third party assurance (TPA) or second party opinion (SPO). Assurance reports assess whether the green issuance is aligned with a reputable international framework, such as the Green Bond Principles (GBP) or Green Loan Principles (GLP). SPOs examine the issuer’s green bond framework, analysing the ‘greenness’ of eligible projects/assets. Not many of them provide a sustainability ‘rating’ – a qualitative indication of the issuer’s framework and planned allocation of proceeds. Post-issuance review is mostly through impact reporting. Having a robust bond framework which lays down the underlying principles will greatly help increase the credibility and transparency of the green bonds market.

Sixth, there should be emphasis on enlarging institutional capacity for the green bonds market. There are many steps involved in sovereign thematic bond issuance—identifying the projects, implementing, monitoring, and evaluation. It is thus immensely important to have coordination between multiple agents and institutions within a government, as well as technical expertise, which is often lacking in emerging markets. India released its sovereign bond framework in 2022, wherein it constituted a Green Finance Working Committee (GFWC) responsible for selecting eligible green projects.

2. The G20’s Role

The G20 economies represent 85 percent of global GDP and 75 percent of global trade.[13] They also contribute 75-80 percent of total greenhouse gas emissions.[14] Climate finance can accelerate their transition to a low-carbon economy. The 2015 Paris Agreement set a goal of limiting temperature rise to 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels by 2030. To reach the target, it is imperative that finance is mobilised for developing economies. Green bonds can attract a larger and more diversified investor group (Berensmann, Dafe, & Lindenberg, 2017).

Green bonds have been issued in many countries. European countries taken together have been the most active, followed by the US, China, and supranational issuers. They are a popular financial instrument across other G20 economies as well. In 2016, when China was G20 president, the grouping published the Green Finance Synthesis Report, which analysed the barriers to green financing and suggested solutions. The key suggestions were to mobilise private financing, support the development of local green bonds markets, promote voluntary principles, and encourage and facilitate knowledge sharing on environmental risk for green finance.[15] The G20 also discussed closely the 2017 Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) report Investing in Climate, Investing in Growth,[16] which provides evidence-based analysis of how fiscal and structural reforms, combined with coherent climate policy, can generate sustainable growth that significantly reduces climate risks.

The G20 can bolster the growth of green bonds by harmonising green bonds standards. This would help diversify the investor base.

3. Recommendations to the G20

The future of green bonds depends on good governance and political stability, developed capital markets, and investor demand. A Sustainable Banking and Finance Network (SBFN) score computed by the International Finance Corporation (IFC) measures countries based on various indicators such as governance, capital market development, and momentum of green bond issuance.[17] Among the G20 economies, China ranks the highest, while India and Saudi Arabia are at the bottom. Thus, countries should focus on improving their governance to attract more investors into their green bonds markets.

G20 countries also need to channel funds into adaptation financing, a segment which lags compared to mitigation financing. While adaptation financing has its limitations including the difficulty of defining the boundaries of adaptation, it is critical that governments focus on improving their scope.

The main recommendations are as follows:

- Reassess national policies: National policies should be reassessed to structurally transform the economy towards low-emission and climate resilience, and eventually net-zero emissions. Policies could include subsidies to manufacturers, incentives to consumers, and benefits to investors making an effort to de-carbonise the economy.

- Grow local currency debt: There is growing interest among emerging economies for local currency issuances. India can lead this initiative under G20 priority. This will help countries avoid an external debt trap.

- Increase awareness: Listing a green bond on one or more exchanges creates greater awareness and expands access for potential investors, increasing the likelihood of reducing borrowing costs. For instance, Fiji listed its sovereign green bond on the London Stock Exchange, which has helped it gain pricing transparency as well as access to international investors. A G20 Green Finance Study Group survey found 74 percent of respondents citing lack of awareness as a crucial barrier in the green bonds market.[18]

Attribution: Cledwyn Fernandez, “Challenges and Opportunities of Green Bonds for Infrastructure Financing,” T20 Policy Brief, July 2023.

Bibliography

Caramichael, John, and Andreas C. Rapp. “The green corporate bond issuance premium,” International Finance Discussion Paper 1346 (June 2022): 1-45.

Fay, Marianne and Julie Rozenberg. “Making Infrastructure Needs Assessments Useful and Relevant.” In Beyond the Gap: How Countries can Afford the Infrastructure they need while Protecting the Planet, edited by Julie Rozenberg and Marianne Fay, 29-43. Washington DC: World Bank Group, 2019.

Kathrin, Berensmann, Florence Dafe, Miriam Kautz, and Nannette Lindenberg. “Demystifying Green Bonds”. In Research Handbook of Investing in The Triple Bottom Line, edited by Sabri Boubaker, Douglas Cumming, and Duc Khuong Nguyen, 333-352. Edward Elgar Publishing, 2018.

Yoshino, Naoyuki, and Farhad Taghizadeh-Hesary. “Alternatives to private finance: Role of fiscal policy reforms and energy taxation in development of renewable energy projects.” In Financing for Low-carbon Energy Transition: Unlocking the Potential of Private Capital, edited by Venkatachalam Anbumozhi, Kaliappa Kalirajan, and Fukinari Kimura, 335-357. Springer, 2018.

Endnotes

[a] Data accessed on March 2023

[1] “10 Years of Green Bonds: Creating the Blueprint for Sustainability across Capital Markets”, World Bank, accessed on July 6, 2023.

[2] “Sustainable Debt Tops $1 Trillion in Record Breaking 2021, with Green Growth at 75%,” Climate Bonds Initiative, last modified April 25, 2022.

[3] International Finance Corporation, Emerging Market Green Bonds Report 2021 (Washington DC: International Finance Corporation, 2021)

[4] Farah Hussain, Helena Dill, and Banu Kayaalp, “Sovereign Green, Social, and Sustainability Bonds: Mobilizing Private Sector Capital for Emerging Markets,” World Bank Blogs, November 8, 2022.

[5] Mutua David, “Global ESG Bond Issuance Headed for First Full-Year Decline Ever,” Bloomberg, December 7, 2022.

[6] Moore Elaine, “Poland issues world’s first green bond,” Financial Times, December 12, 2016.

[7] Gong Chen, Torsten Ehlers and Frank Packer, “Sovereigns and Sustainable Bonds: Challenges and new options,” Bank for International Settlements, September 19, 2022.

[8] International Capital Markets Association, Green Bond Principles: Voluntary Process Guidelines for Issuing Green Bonds (Zurich: ICMA, 2021).

[9] “Disclosure requirements for issuance and listing green bonds,” Securities and Exchange Board of India, accessed 2023.

[10] “Greenwashing: CMA puts businesses on notice,” GOV.UK, last modified September 20, 2021.

[11] Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), Green Bonds: Country Experiences, Barriers and Options (Paris: OECD, 2015).

[12] Vorisek Dana and Yu Shu, Understanding the cost of achieving the sustainable development goals (World Bank, 2020).

[13] Press Information Bureau, “100th G20 Meeting during India’s 20 Presidency”.

[14] “G20 economies are pricing more carbon emissions but stronger globally more coherent policy action is needed to meet climate goals, says OECD,” OECD, last modified October 27, 2021.

[15] G20 Green Finance Study Group, G20 Green Finance Synthesis Report, (Toronto: University of Toronto, 2016). (utoronto.ca)

[16] Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, Investing in Climate, Investing in Growth (Paris: OECD, 2017).

[17] “Sustainable Banking and Finance Network (SBFN),” International Finance Corporation, accessed 2023.

[18] Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), Green Bonds: Country Experiences, Barriers and Options