Task Force 6: Accelerating SDGs—Exploring New Pathways to the 2030 Agenda

By taking a gender-transformative and a rights-based entitlement approach, this Policy Brief stresses the importance of investing in the care economy within the context of COVID-19 recovery plans, the G20 agenda of striving for just and equitable growth, and India’s Vision 2047. Ensuring greater gender equality in the distribution of paid and unpaid work can be socially transformative and enhance gross domestic product. This Brief explores inequality within the care economy in India, specifically focusing on the unpaid care work, paid work, and paid care work circles, and their negative impacts. It further describes the challenges and importance of investing in care, with a particular focus on childcare provision. This Brief recommends positioning care as a fundamental pillar of a lifecycle social protection system and economic growth trajectories, with investment in the provision of care services as a public good provided by the state.

1. The Challenge

The COVID-19 pandemic brought to light the importance of care work as a fundamental pillar of an inclusive society and a growing economy. However, most care work is unpaid,[1] and women spend two to ten times more time on unpaid care work than men.[2] Time spent on these unpaid activities is closely linked with gender inequality in labour force participation, social protection (SP) access, wages, job quality, and overall wellbeing and empowerment.

Unpaid care work by women and girls results in them providing a public good without being compensated for it.[3] Unpaid work undertaken by women amounts to as much as US$10 trillion of output per year, which is roughly 13 percent of global GDP.[4] Care work “is what sustains individuals and families from day to day, and from one generation to the next,” and it also “sets the foundation for all other economic activities.”[5]

Not only is it necessary for the state to provide care but also recognise the value of and legislate unpaid care work in the economy. This can be done through a political and normative framework. The state has a responsibility to ensure proper investment in an inclusive lifecycle SP system that includes care as a fundamental pillar of wellbeing.

Care pillar within an inclusive and lifecycle social protection system

Care is a central requirement for a society’s wellbeing. It is a transversal activity that has an impact at the private, public, and community levels, but it is currently organised in an unfair manner, which reproduces inequalities across society.

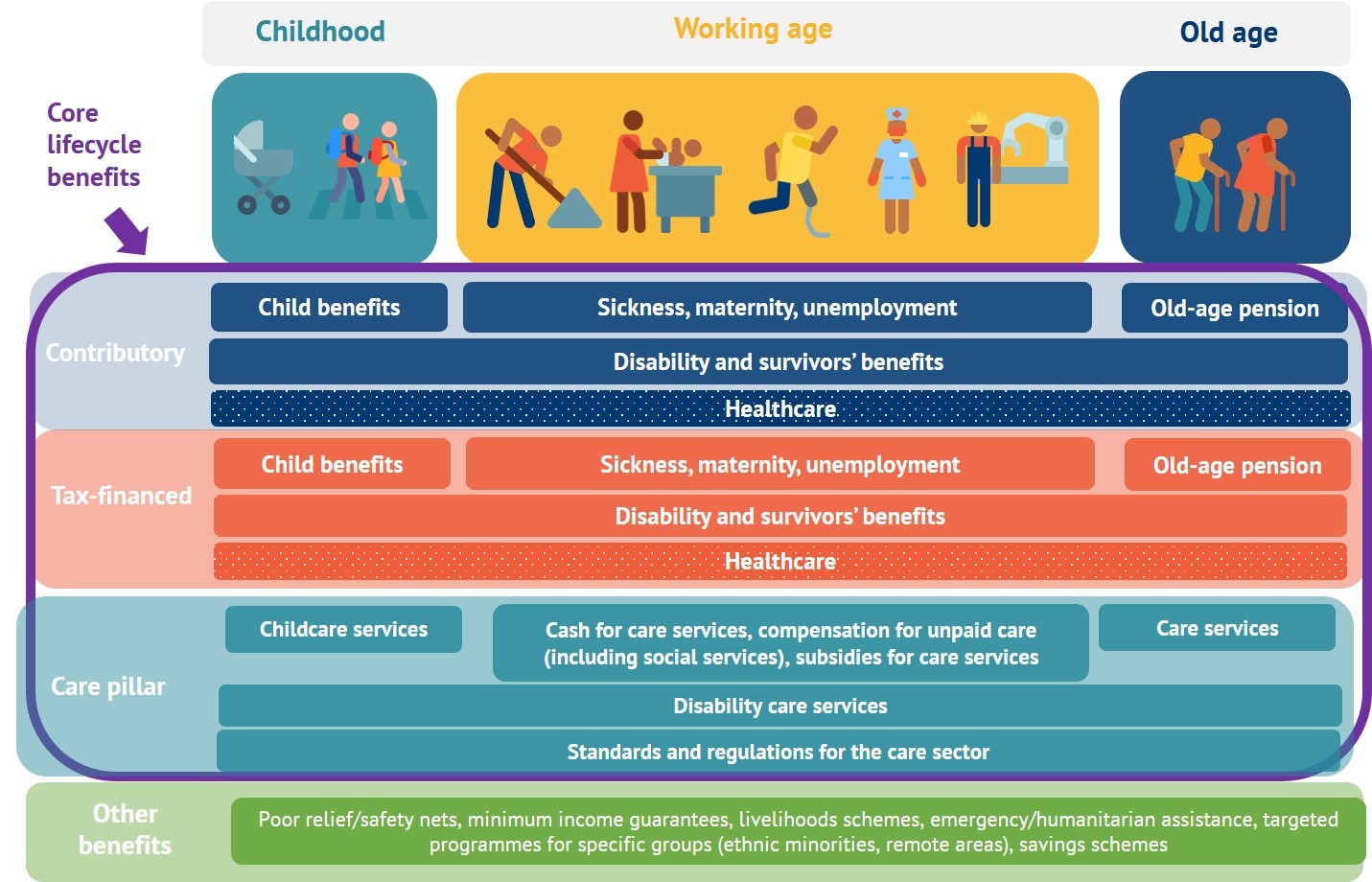

The care pillar is central to any inclusive and lifecycle SP system and should be conceived as a public good (see Figure 1). The state therefore has a responsibility to provide adequate, accessible, and affordable care services to individuals throughout their lifecycle. Unfortunately, privatised services in other sectors—for the provision of other social and economic rights, such as education and health—have resulted in lower-quality services, unequal access, inequities, segregation, and the reinforcement of unbalanced power relations.[6]

Figure 1: Lifecycle Social Protection Schemes and Care Pillar

Source: Development Pathways for UNICEF India

For SP to be transformative, it must assist countries in redistributing unpaid care work.[7] Inclusive and transformative SP necessitates public investment in care services, as shown in Figure 2. This approach is crucial for establishing a new social contract amidst structural inequalities and fostering a new gender contract based on justice.[8]

Figure 2: Public Expenditure on Selected Care Policies as a Percentage of GDP and Employment-to-Population Ratio

Source: ILO (2018), UNESCO (2018), ILO (2017), and OECD (2017)

The International Labour Organization (ILO) Recommendation 202[9] establishes the basic social security guarantees needed for a SP floor, including children’s access to care, maternity care, and maternity benefits. Thus, a care policy package should “include a combination of time (leave), benefits (income security), rights and services to enable the right to care and be cared for and to promote gender equality and decent work.”[10] Care policies also need to be designed from lifecycle and rights-based approaches.[11]

Access to quality and affordable care services—childcare, elderly care, and care for people with disabilities—is a global challenge. It is important to design an ecosystem of transformative care policies and linkages to changing demographics. Given that unpaid domestic work compensates for the state[12] not providing adequate childcare services,[13] there has been a widespread international call for the valuation of care work, which has resulted in the Triple R Framework—recognising, reducing, and redistributing unpaid care work.[14] It urges policymakers to recognise and challenge the assumption that care work is a domestic and private issue; reduce the time devoted to unpaid care work; and redistribute the burden of care work, both between men and women and, more importantly, among households, society, and the state. The ILO has proposed two additional Rs—rewarding care workers with more and decent work and enabling their representation in social dialogue and collective bargaining.[15]

To achieve gender-transformative SP, countries need to invest in the care economy. As shown in Figure 2, most countries with higher rates of investment in care policies have high rates of working women with care responsibilities. The Nordic model of subsidised, affordable, and quality childcare services and generous shared parental leave has allowed them to have a larger share of their women in paid employment.[16] Figure 2 also shows low levels of investment in care for India, and a relatively low rate of working women with care responsibilities.

Extending quality childcare provisions can improve health, education, and development outcomes for children, improve women’s participation in the labour force, and create decent work in the paid care sector that can help regularise informal sectors of the economy.[17] Improving childcare and women’s opportunities to work can also improve business productivity, bring benefits associated with diversity, and contribute to economic growth by increasing income from a higher female labour-force participation rate (FLFPR).[18] Empowering communities and care service providers is a fundamental aspect of ensuring that SP policy solutions are transformative and inclusive.

2. The G20’s Role

This section outlines the need for priority investments in the G20 countries, using India as an example.

Overview of India’s care economy

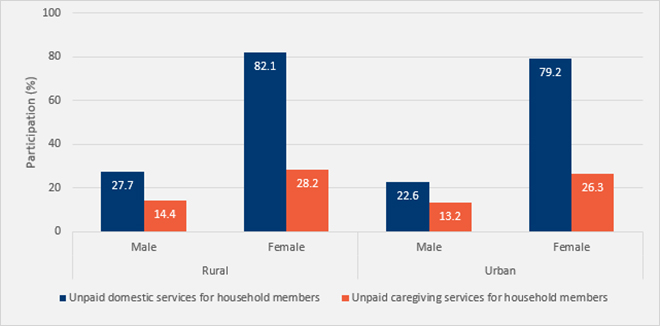

The Indian economy is characterised by high levels of informality for both men and women, but women also generally carry out most of the unpaid care work within their households and extended families. The last Time Use Survey (TUS) in India highlighted how unpaid domestic and caregiving work is mostly a woman’s activity (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: Participation in Unpaid Domestic and Caregiving Services by Sex and Location

Source: India Time Use Survey (2019)

Men’s involvement in unpaid caregiving and domestic work is significantly lower compared to women. On average, women spend 433 minutes a day (approximately 7.2 hours), whereas men spend only 173 minutes (approximately 2.8 hours) on these tasks.[19] This has a stark impact on time poverty, whereby women do not have much choice on how to allocate their scarce time.[20] The unbalanced burden on unpaid care also translates into foregone earnings from paid labour.[21]

According to the ILO, the value of unpaid care work (monetary value equivalent to the minimum wage) would be 0.4 percent of the GDP for men and 3.1 percent of the GDP for the unpaid work done by women.[22] Considering that women represent 99.4 percent of the workforce performing care or domestic work, the ILO estimated that if this unpaid care work was recognised and there was a direct public investment of 2 percent of GDP in this sector, India would create around 11 million new jobs.[23]

India also has one of the lowest FLFPR, with only 19 percent of all women of working age engaging in formal employment.[24] India has witnessed a significant drop in FLFPR in the past 20 years, even in a context of rising incomes, improved literacy levels for women, and economic growth. The low FLFPR reflects the undervaluation of women’s employment and ‘invisibilisation’ of the care economy. Figure 4 shows the female-to-male ratio of labour force participation versus female-to-male ratio of time spent in unpaid care work, thus highlighting a huge potential for India in developing a paid care sector.

Figure 4: Female-to-Male Ratio of Labour Force Participation Versus Female-to-Male Ratio of Time Spent in Unpaid Care Work

Source: McKinsey Global Institute (2015) using OECD and ILO data

Progress in social protection and childcare

The disproportionate burden of unpaid care work on women means that even when they engage in paid employment, the weight of unpaid care work remains on them, creating a double burden. It impacts women’s wellbeing as they are not able to access SP, particularly social insurance for when they are old. It is important to note that SP and employment policies that aim at empowering women and strengthening female labour force participation are designed with a concern for the unpaid care work that women are expected to perform in addition to other types of work. While the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA) has been praised for increasing FLFPR in rural areas, it is essential not to conflate increased work participation with women’s empowerment if unpaid care responsibilities are not alleviated.[25] The dynamics and processes of unpaid care work, in both the making and the implementation of the act, should be addressed in order to achieve the goal of women’s empowerment.[26]

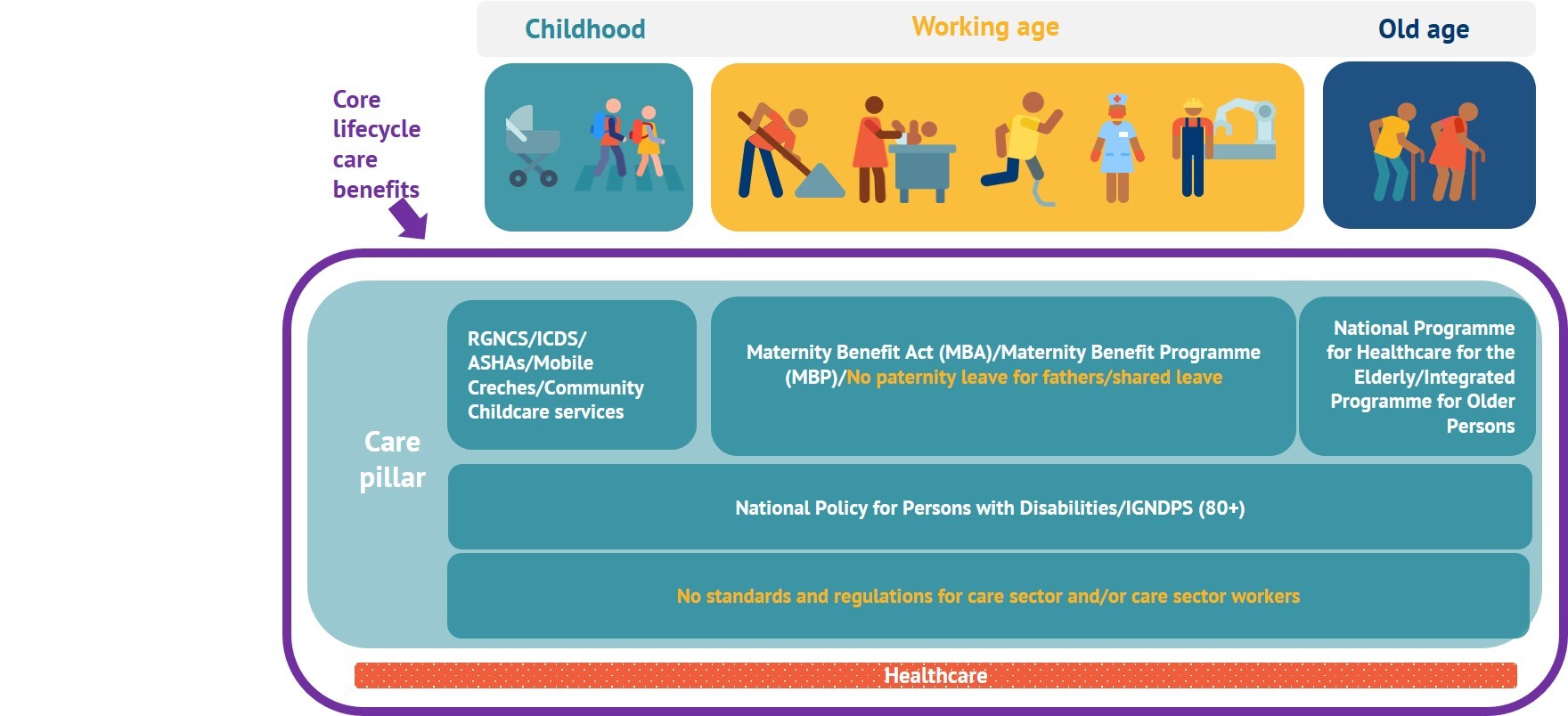

The Government of India ensures care service provision through multiple schemes that address lifecycle gaps. However, like in many G20 countries, these schemes are implemented in silos and fall short of full coverage. Figure 5 shows some of the main care services, which are further described in the following paragraphs.

Figure 5: Core Lifecycle Care Benefits in India

Source: Development Pathways for UNICEF India

Maternity, paternity, and special care leave: The Maternity Benefit Act (MBA) provides women employed in organisations of ten or more employees with 26 weeks of maternity leave—up from 14 weeks. The Maternity Benefit Programme (MBP) provides cash transfers to pregnant and lactating women not receiving maternity benefits from any other source.[27] However, there is no paternity leave for fathers, nor shared leave,[28] and both the MBA and the MBP place childcare duties entirely on women.[29]

Disability care: The Indira Gandhi National Disability Pension Scheme (IGNDPS) is for those aged 18–79 years with 80 percent and above or multiple disabilities and belonging to a Below Poverty Line (BPL) household.[30] In 2014–2015, it had roughly one million beneficiaries, which is significantly below the 2011 census-estimated 26.8 million persons with disabilities in the country.[31]

Long-term care and elder care: Older persons currently receive national-level support from the National Policy on Older Persons, the National Programme for Health Care for the Elderly, and the Integrated Programme for Older Persons.[32]

Childcare: Schemes include the Rajiv Gandhi National Crèche Scheme (RGNCS), mobile crèches, the Integrated Child Development Scheme (ICDS), Self-Employed Women’s Association (SEWA), and Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHAs). Some of these are based on workers who are classified as volunteers. Currently, the fragmented childcare initiatives that are available to families in India are largely informal and fall short of empowering mothers, caregivers, and children, for whom early-age interventions are crucial for improving performance and development levels.[33]

Gaps in care provision

India, like other G20 countries, may not have an explicit policy to support care services. However, progressive efforts are being made to strengthen the care sector, especially with a focus on the early years, which includes provisions for caregivers or childcare workers.[34] Given that a majority of persons engaged in care work operate in an informal capacity, it is essential for the labour laws and regulations governing the Indian economy to offer them with coverage or protection as well as a standardised level of training or formal guidance.[35]

Domestic workers, who are largely female, face significant challenges in being recognised as workers, even when paid, and lack access to workers’ rights and entitlements. The gaps in the care systems in place for them became apparent during the pandemic, as they were left without adequate social or health protection measures while serving as ad-hoc care workers for many dependent households.[36]

The lack of standards and regulations for the care economy leave service providers free to establish services as they best deem fit, leaving care workers unprotected. This can pose dangers in private care service delivery, as there are no standards or principles guiding these services.

Throughout the lifecycle of Indians and in many low and middle-income countries, several gaps exist in the provision of care. Childcare, disability, and old-age care are provided in a somewhat fragmented way, and benefits provided to working-age adults employed in the formal economy (such as maternity benefits) are mostly directed towards women (instead of being equally directed to men in the form of paternity benefits, for example), which reinforces the reliance on women to provide care work within households. The existing childcare services leave unattended gaps, particularly for migrants, unemployed women, and others. This situation negatively impacts the welfare of those requiring care services as well as those providing the unpaid care, primarily women.

Evidence shows that women without children are more likely to work full time, whereas women with children are more likely to work part time or not work at all. As such, providing opportunities for part-time work would encourage female labour force participation.[37]

3. Recommendations to the G20

Given the critical role of child wellbeing in ensuring sustainable development in countries, leaving the level of care received by children up to chance is not an option. Investing in the care economy is investing in child development. As mentioned previously, countries with higher rates of investment, such as the Nordic countries, have subsidised childcare and high rates of working women with care responsibilities. Inaccessible childcare not only has negative impacts for FLFPR but also for school enrolment and drop-out rates. As children grow older, teenagers (especially girls) in the household might be pulled from school to provide house care and childcare support to mothers, particularly if there are young children in need of care.[38] A study looking at South Africa and Turkey estimated that an investment of 3.2 percent and 3.7 percent, respectively, of GDP in childcare would increase employment rates by 6.3 percent (10.1 percent among women) and 4.1 percent (5.7 percent among women), respectively.[39]

Recommendation 1: Care as a core pillar

To strengthen the care pillar in the G20 countries and India, governments should work towards placing care as a core pillar of their lifecycle SP system and economic growth trajectories. This involves investing in the provision of care services as a public good provided by the state. Childcare services could serve as the initial building block for further integrating a public care system, benefiting not only children by providing them with “an equal start in life”[40] but also their primary caregivers (women), the economy, and society as a whole. Universalising access to public childcare institutions and regulating the sector properly would also be a significant advance in gender equity.

Recommendation 2: Gender-inclusive childcare policies

Childcare policies need to be conceived at the national level, from the perspective of women’s unpaid work dynamics and gender equity.[41] Inclusive childcare services that account for the unpaid care burden is a crucial component of achieving greater gender equality and accelerating economic growth by 2047 in India. This should be done with a nuanced understanding of the complex interactions between formal and informal institutions, paid and unpaid work, and ensuring that care policies are gender-sensitive from the onset. As such, childcare provision should have universal access, regardless of employment status or location, and address the key constraints that families face in accessing these services. Likewise, childcare policies should advocate and encourage greater participation of men, including the provision of paternity leave, to promote shared caring responsibilities.

Recommendation 3: Quality care sector in G20 countries

The care sector in G20 countries must be built upon sound standards and regulations, ensuring high-quality service provision aligned with human rights principles. These guidelines should be applicable to both public and private care service providers, formalising the job of care workers, particularly those under volunteer-based schemes who are paid incentives rather than proper salaries. It is essential to professionalise care services without compromising community care work service delivery or the contribution of workers engaged in unpaid or underpaid care work. Moreover, privatising care work services should be avoided, as it is a public good and integral to an inclusive lifecycle SP system. Finally, childcare services should be seen as an equalising opportunity by offering affordable, subsidised, and high-quality services while respecting the rights of users and care workers.

Attribution: Hyun Hee Ban et al., “Care Economy and Gender Transformative Social Protection in India and the G20 Countries,” T20 Policy Brief, August 2023.

Endnotes

[1] Diya Dutta, “No Work is Easy! Notes from the Field on Unpaid Care Work for Women,” in Mind the Gap: The State of Employment in India 2019 (Oxfam India, 2019), 102.

[2] Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Development Centre, Unpaid Care Work: The Missing Link in the Analysis of Gender Gaps in Labour Outcomes (OECD, 2014).

[3] Francis Kuriakose and Deepa Iyer, “India in Transition: ‘Care’ Economy Uncharitable to Women,” The Hindu Business Line, December 6, 2021.

[4] McKinsey Global Institute, The Power of Parity: How Advancing Women’s Equality Can Add $12 Trillion to Global Growth (McKinsey & Company, 2015).

[5] Kristina Lanz, “Interview with Shahra Razavi: Global Trends, Challenges and Controversies in the Areas of Care, Work and Family Relations,” in Transitioning to Gender Equality, ed. Christina Binswanger and Andrea Zimmermann (MDPI, 2021), 163.

[6] Sarah. K. Jameson and Sylvain Aubry, State’s Human Rights Obligations Regarding Public Services (The Global Initiative for Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, 2020).

[7] United Nations Research Institute for Social Development (UNRISD), Crises of Inequality: Shifting Power for a New Eco-Social Contract, UNRISD Flagship Report (UNRISD, 2022).

[8] UNRISD, “Crises of Inequality”

[9] International Labour Organisation (ILO), R202: Social Protection Floors Recommendation (ILO, 2012).

[10] ILO, Care Work and Care Jobs for the Future of Decent Work (Geneva: ILO, 2018).

[11] ILO, “Care Work and Care Jobs”

[12] Indira Hirway, “Unpaid Work and the Economy: Linkages and Their Implications,” Working Paper No. 838 (Levy Economics Institute of Bard College, 2015).

[13] Oxfam, Mind the Gap: The State of Employment in India in 2019, Oxfam Working Paper Series: India Inequality Report (Oxfam, 2019).

[14] ILO, “Care Work and Care Jobs”

[15] ILO, “Care Work and Care Jobs”

[16] Nordic Council of Ministers, Subsidised Childcare for All: The Nordic Gender Effect at Work (Nordic Council of Ministers, 2019).

[17] International Trade Union Confederation, Investing in the Care Economy: A Pathway to Growth (Brussels: ITUC, 2016).

[18] Amanda. E. Devercelli and Frances Beaton-Day, Better Jobs and Brighter Futures: Investing in Childcare to Build Human Capital (The World Bank, 2020), http://hdl.handle.net/10986/35062.

[19] Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation, India Time Use Survey 2019 (Government of India, 2019).

[20] Sanchari Ghosh, “Maternity Leave in India: Past, Present and Future,” Journal of Social Sciences 7–8, no. 1 (2019): 35–41.

[21] Ghosh, “Maternity Leave in India”

[22] ILO, “Care Work and Care Jobs” 50.

[23] Dutta, “No Work is Easy!”

[24] World Bank, Labour Force, Female (% of Total Labour Force), India, World Development Indicators Database, 2022.

[25] Deepta Chopra, Taking Care into Account: Leveraging India’s MGNREGA for Women’s Empowerment (The Hague: International Institute of Social Studies, 2019).

[26] Chopra, “Taking Care into Account”

[27] Ritu Dewan, Invisible Work, Invisible Workers: The Sub-Economies of Unpaid Work and Paid Work. Action Research on Women’s Unpaid Labour (ActionAid, 2017).

[28] Ghosh, “Maternity Leave in India”

[29] Dewan, “Invisible Work, Invisible Workers”

[30] Government of Odisha, Dhenkanal District, Indira Gandhi National Disability Pension Scheme (IGNDPS).

[31] Lorraine Wappling, Rasmus Schjoedt, and Daisy Sibun, “Social Protection and Disability in India,” Development Pathways Working Paper (Development Pathways, 2021).

[32] Wappling, Schjoedt, and Sibun, “Social Protection and Disability”

[33]i TD Economics, Special Report Early Childhood Education Has Widespread and Long Lasting Benefits (TD Economics, 2012).

[34] Dagmar Walter, “Getting Serious About Supporting the Care Economy,” ILO, April 29, 2022.

[35] International Trade Union Confederation, ITUC Report on Care: Putting the Care Economy in Place (ITUC, 2022).

[36] Walter, “Getting Serious”

[37] Shamindra N. Roy and Partha Mukhopadhyay, “What Matters for Urban Women’s Work: A Deep Dive into Female Labour Force Participation,” in Mind the Gap: The State of Employment in India 2019 (Oxfam India, 2019).

[38] Roy and Mukhopadhyay, “What Matters”

[39] Jerome De Henau et al., “Investing in Free Universal Childcare in South Africa, Turkey and Uruguay,” UN Women Discussion Paper Series No. 28 (UN Women, 2019).

[40] Nordic Council of Ministers, “Subsidised Childcare for All” 41 Dewan, “Invisible Work, Invisible Workers”