Abstract

The transmission of external shocks via trade and financial channels from advanced economies to emerging and developing economies has occurred during several turbulent episodes. This policy brief documents factors that may help build resilience to such shocks. It emphasises that G20 nations must resort to policy coordination, renew the emphasis on trade ties, strengthen the financial architecture, and enhance global supply chains to cope with the impact of external shocks.

- The Challenge

The global economy has been in flux as it is reeling under the influence of geo-political events such as the Russia-Ukraine war, leading to a sluggish pace of growth, a dip in business confidence, tighter financial conditions, and increasing policy uncertainty. The last two decades have been marked by several notable events, such as the recession of 2008-09, the Eurozone sovereign debt crisis of 2011-12, and the economic predicament of the COVID-19 pandemic[1][a] that have been sources of turbulence for advanced economies (AEs) and emerging and developing economies (EMDEs) alike. The first two resulted from economic and financial disruptions in major AEs. However, the COVID-19 pandemic was a health crisis unlike any seen before and led to a severe contraction in economic activity. These external shocks impacted economies worldwide by severely constraining growth and fracturing financial markets. Additionally, such external shocks have led to slow pick-ups in economic activity, low investment, sluggish aggregate demand, increasing uncertainty, low business and consumer confidence, supply-side disruptions, poor financial market sentiment, volatility in commodity prices, and changes in the behaviour of economic agents.

It is well known that economic and financial crises are recurrent and persistent phenomena. Global integration in the form of pronounced trade and financial links has been a catalyst for the spread of external shocks and has made economies vulnerable. Both AEs and EMDEs have witnessed systemic failure in financial markets, exposing fragilities in the global financial system. EMDEs, however, are more susceptible to external shocks, since they are affected by shocks originating within their economy and those transmitted from AEs.

External shocks, magnified by globalisation and reinforced by economic linkages, lead to greater synchronisation in economic activity. Examination[2] of the synchronisation of recessions in major AEs and EMDEs during the Great Recession shows that EMDEs[b] did not undergo recessions but only milder slowdowns. However, later work finds that the recession accompanying the COVID-19 pandemic has been the most synchronised, surpassing even the one caused by the global financial crisis of 2008-09.[3][4] As a result, the fastest-growing EMDEs, such as China and India, also experienced recessions[c] during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Therefore, the challenges presented by external shocks are critical, particularly for EMDEs, which are more prone to external shocks from AEs and volatile global financial markets. It is critical that the G20 economies build resilience to these external shocks. What, then, are the channels of transmission of external shocks to EMDEs? What factors could potentially shield the economies from external shocks? What role could be played by the G20 nations in creating a systemic response to external shocks? This policy brief discusses external shocks from AEs to EMDEs and presents a few resilience indicators in the next two sub-sections.

Resilience to external shocks

External shocks, largely affecting EMDEs, may be classified into those arising from trade and financial linkages, supply shocks, natural calamities, and common shocks due to a pandemic or rise in the price of crude oil. Climate change has made the task of achieving economic growth even more arduous due to increasing instances of natural calamities, which along with pandemics, severely impact global supply chain networks and have a profound impact on growth.

Transmission of economic disturbances from AEs to EMDEs occurs via the current account and capital account (i.e., from the balance of payments or BoP). Stronger trade linkages lead to the amplification of shocks which are transmitted across trading partners via the Current Account of the BoP. One outcome of financial globalisation has been the rapid spread of negative financial shocks across the globe, resulting in cascading downturns in financial markets worldwide. This is due to the simultaneous sale of stocks by foreign institutional investors (FIIs), who hold internationally diversified portfolios and operate via the Capital Account. In this case, a steep fall in capital flows to EMDEs is expected, owing to increased uncertainty and a dampening of global investment.

Therefore, a negative global demand shock can be transmitted to EMDEs through trade shocks due to a lowering of the export demand for domestic goods and services, and/or via financial shocks resulting from a slump in the demand for domestic EMDE assets. As a result, the central banks of EMDEs must contend with a deterioration in foreign exchange reserves and lower import cover attributable to pressure on the Current and Capital accounts.

It is notable that common shocks, such as the COVID-19 pandemic,[d] have a more widespread negative influence on global growth as they derail trade links and disrupt global supply chains[5]. The pandemic was an unforeseen health shock to the global economy that had a direct impact on employment and standards of living due to its unprecedented nature, significant output loss, uncertainty regarding its duration and intensity, and the need for innovative medical and economic policy to combat the crisis’ effects. It was marked by a push-pull between expansionary economic policies on the one hand and public health initiatives on the other. This is because common shocks, such as government-mandated lockdowns to stop the spread of a virus, significantly impacted growth by reducing economic activity. These effects have multiplied and spread around the globe through trading partners, financial borrowers, and lenders connected by global value chains.

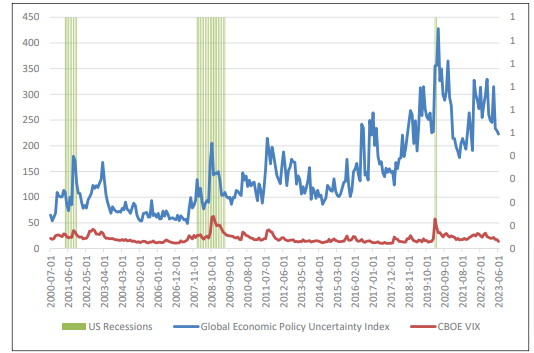

This policy brief analyses the relationship between financial market volatility, recessions, and policy uncertainty by depicting periods of heightened global economic policy uncertainty,[6] volatility in financial markets captured by the Chicago Board Options Exchange Volatility Index (VIX), and US recessions (see Figure 1). Periods of high financial market volatility and economic policy uncertainty potentially overlap with recession dates in the US,

Figure 1: Global Economic Policy Uncertainty, Volatility (VIX), and US Recessions

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis and NBER

A critical aspect of policy design Plugging economic risks that arise due to policy uncertainty is a critical aspect of policy design. Further, policy options available to EMDEs may be restricted due to several constraints, including that of resources, finances, access to R&D, technology, and skilled labour.

Resilience indicators

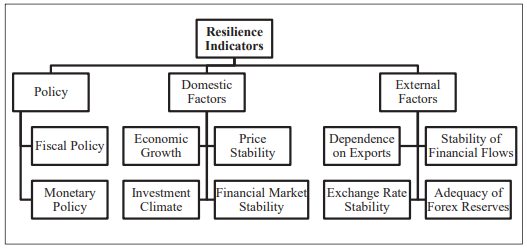

This policy brief will formulate resilience indicators[7] that suggest the ability of an economy to withstand the effects of an external shock (see Figure 2).[8],[9]

Figure 2: Resilience Indicators for G20 Economies

Source: Authors’ Contribution

Policy Headroom: The first among these shows the policy headroom available to the economy to mitigate the effects of any external shock. These are captured by the policy space on the fiscal as well as the monetary sides.[e],[10] In response to an external crisis, policymakers may need to resort to policy expansions. Therefore, these are key variables that capture the ability of the nation to endure external shocks.

Domestic Factors: The second category consists of indicators which capture the momentum of growth in the economy. These include economic growth rate, investment climate, stability of prices, and the financial system. An external shock is likely to slow down growth in the economy. However, with strong fundamentals, such as thriving domestic demand and stable financials, the economy can withstand the crisis and bounce back to its growth trajectory faster.

External Factors: The last category focuses on those aspects of the economy that are directly affected by the shocks and are grounded in the factors discussed earlier. The ability of an economy to withstand external shocks relates to its dependence on exports as a channel of growth, the stability of its exchange rate and that of Foreign Direct Investment flows to the economy vis-à-vis the FII flows, and adequacy of its existing foreign exchange reserves.

The G20 includes 20 member nations which are divided into AEs viz. Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the UK, the US, the European Union, the Republic of Korea, and Australia and EMDEs including Indonesia, Argentina, Mexico, Türkiye, Saudi Arabia, and BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) economies. Some of the resilience indicators for the AEs and EMDEs are as follows:

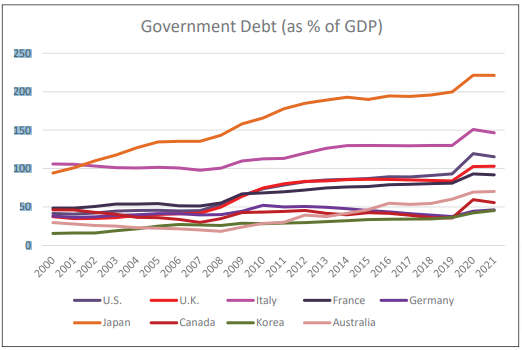

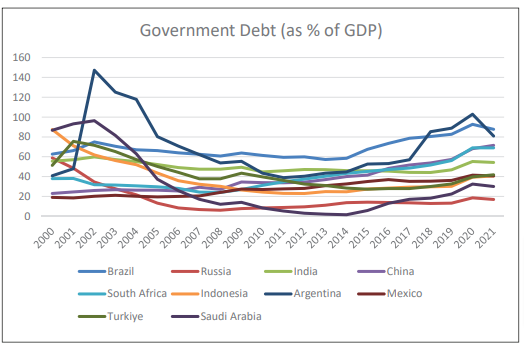

The government debt levels of Japan and Italy are more than 100 percent of the GDP (see Figure 3, Panel A), and those of EMDEs are inching towards the 100 percent figure, except for Argentina (see Figure 3, Panel B).

Figure 3: Fiscal Debt

Panel A: AEs

Panel B: EMDEs

Source: IMF (Data is as per availability)

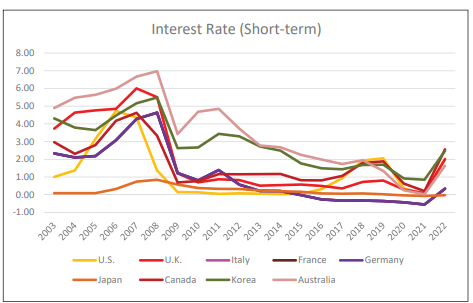

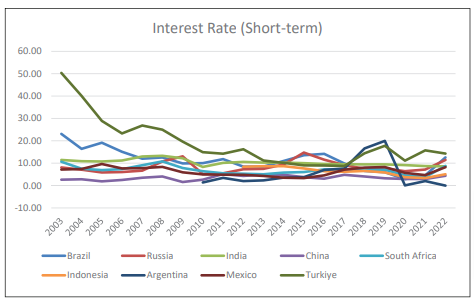

Several AEs have hit the zero lower bound on interest rates and are increasingly resorting to unconventional monetary policy measures (see Figure 4, Panel A). However, EMDEs have utilised a combination of conventional and unconventional monetary policies to tackle external shocks, such as the COVID-19 pandemic (see Figure 4, Panel B).

Figure 4: Interest Rate (Short-term)

Panel A: AEs

Panel B: EMDEs

Source: OECD Stat (Data is as per availability)

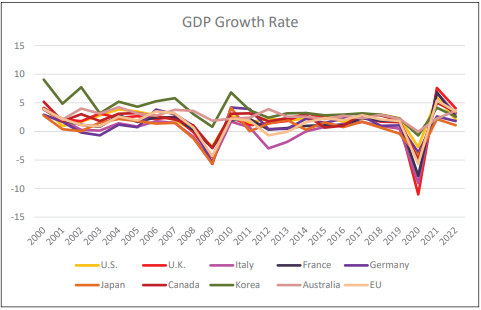

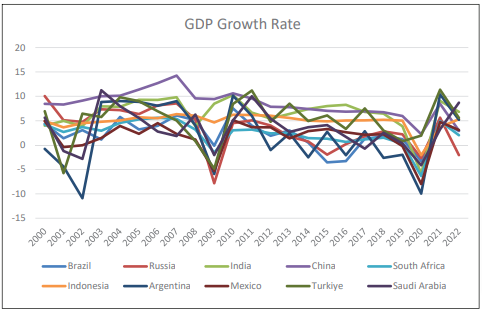

External shocks in the form of the global financial crisis, the Eurozone Sovereign debt crisis, and the COVID-19 pandemic severely affected GDP growth rates across the board (see Figure 5).

Figure 5 GDP Growth Rate

Panel A: AEs

Panel B: EMDEs

Source: World Bank

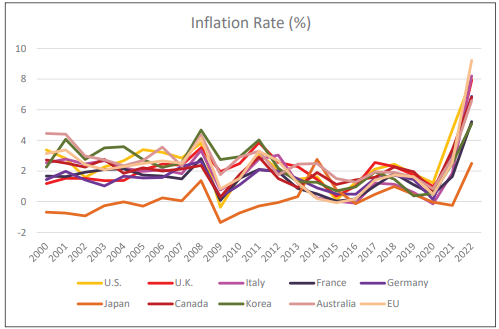

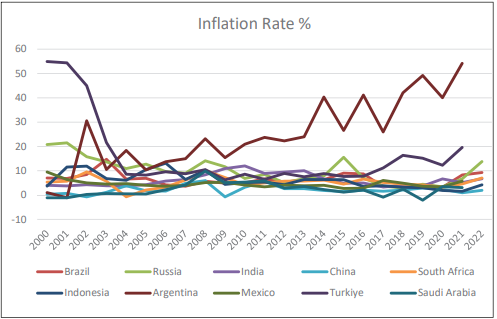

Figure 6 suggests the recent pandemic has renewed inflationary pressures globally, across both AEs and EMDEs.

Figure 6: Inflation Rate

Panel A: AEs

Panel B: EMDEs

Source: IMF and World Bank

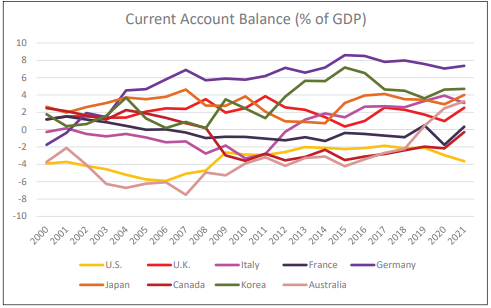

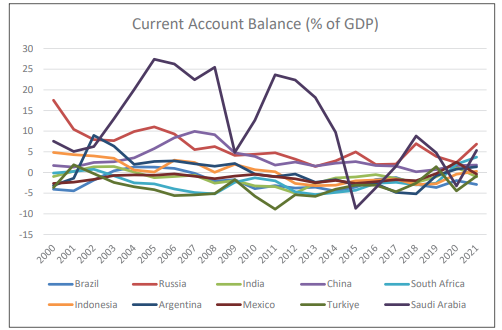

Figure 7 indicates that the developed economies of the US, Canada, and France, along with several EMDEs, have negative current account balances.

Figure 7: Current Account Balance

Panel A: AEs

Panel B: EMDEs

Source: World Bank

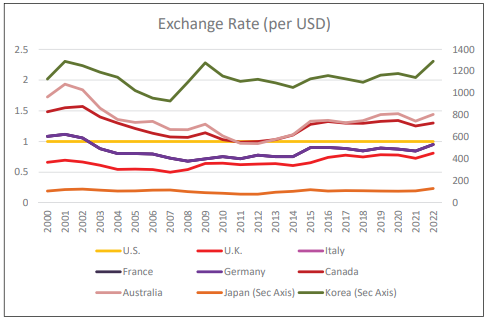

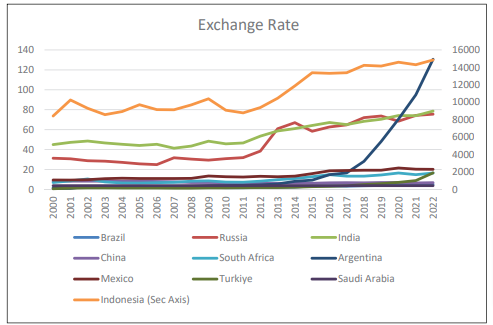

The developed economy currencies are stable, but the EMDE exchange rates are volatile (see Figure 8, Panel A).

Figure 8: Exchange Rate

Panel A: AEs

Panel B: EMDEs

Source: World Bank

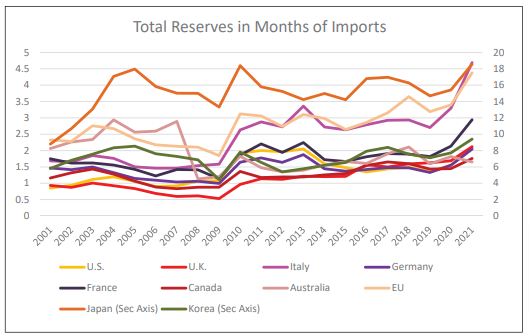

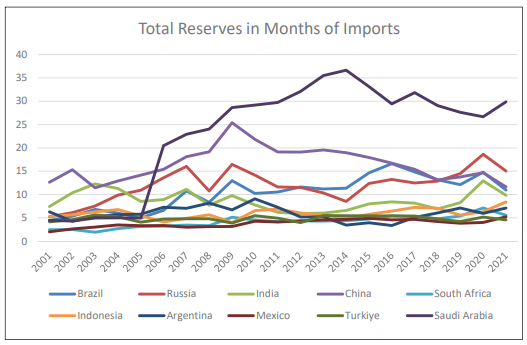

Finally, Figure 9, Panel A shows that among the AEs, Japan and South Korea, have been keeping a buffer in foreign exchange reserves. However, due to the stability of their currencies, the remaining AEs have not accumulated stocks of foreign exchange reserves. On the other hand, EMDE central banks have been piling up a few months of foreign exchange reserves to deal with exigencies.

Figure 9: Foreign Exchange Reserves

Panel A: AEs

Panel B: EMDEs

Source: World Bank

On the one hand, AEs deal with a very different set of fundamentals, such as low interest rates and growth but stable exchange rates. On the other hand, EMDEs have experienced more volatility but higher growth, and are susceptible to currency fluctuations. To circumvent the zero bound interest rate and a liquidity trap kind of situation, AEs cannot utilise traditional monetary expansion as it is ineffective and resort to unconventional measures like Quantitative Easing.

- The G20’s Role

The G20 accounts for 85 percent of global GDP, 75 percent of global trade, and two-thirds of the world’s population. One of the focal points of the G20 is to ensure international cooperation on economic and financial issues. Given that the G20 was created in the aftermath of the Asian Financial crisis of 1997-98, crisis resolution remains at the heart of the forum. It has a major role in creating a consensus on critical areas of macroeconomic cooperation, which includes swift response to global shocks. Last year, when the forum met in Bali, Indonesia, it reiterated its commitment towards tackling global challenges and engendering sustainable global growth.

The Bali Declaration of G20 nations (2022) stated that the economies would “stay agile and flexible in (our) macro-economic policy responses and cooperation.” The Declaration renewed the G20’s commitment towards using available tools to mitigate downside risks in the aftermath of the Great Recession of 2007-09, in addition to making the required public investment and taking up structural reforms to strengthen trade and global supply chains, which will support sustainable global growth. It was agreed that fiscal and monetary policy tools may be utilised by central banks to ensure price stability.

It is clear that the G20 countries need to develop a common strategy, using the forum to tackle the recurrent economic slowdowns and, more specifically, global recessions caused by external shocks emanating from the AEs. One such avenue is policy coordination among the G20 member countries, which, in terms of fiscal or monetary expansion, can shield economies from disproportionate impact via the BoP.

International cooperation on macroeconomic policies and creating a conducive environment for the same is key to finding timely resolution and reaction to global economic, financial, and health shocks. Therefore, the G20 has a significant role in containing the economic impact of external shocks. Multilateral cooperation is vital for addressing issues of international macroeconomic relevance.

- Recommendations to the G20

The following recommendations to the G20 are related to policy headroom, domestic aspects, and external factors, viz., trade ties, financial linkages, and supply-side disruptions due to common shocks. Notably, macroeconomic policy coordination is particularly important in the context of common shocks.

- Policy space and partnerships:

The G20 must continue its strong commitment towards tackling severe crises by emphasising strong macroeconomic fundamentals and by encouraging swift policy actions by governments and central banks. Periods of high volatility in financial markets, policy uncertainty, and negative economic activity are clustered together. Therefore, it is critical to reduce policy uncertainty by improving central bank communication.

AEs and EMDEs may engage in ‘triangular cooperation’ to leverage complementary strengths to co-create innovative solutions which help achieve economic growth. AEs must participate in transferring technology and know-how to EMDEs, as the latter are more susceptible to external shocks.

An important avenue to address emerging downside risks and future crises is macroeconomic policy coordination, both fiscal and monetary, among the members. Given that several countries may be working with limited policy space, timely coordination of both monetary and fiscal policies is needed to abate the impact of common shocks. The role of multilateral development banks cannot be emphasised enough in this context.

- Domestic aspects:

It is important to safeguard the recovery of investment and ensure the renewal of employment opportunities in EMDEs to revive global growth. Supplementation of monetary policy with expansionary fiscal policy was utilised by many economies during the COVID-19 crisis. Fiscal expansion, along with public investment, is urgently required to salvage growth at this stage. Addressing the issue of climate change is also paramount as its mitigation requires investment and coordinated policies to translate into sustainable growth and development.

- External factors:

- Strengthen trade ties:

Trade agreements may help renew trade ties, which were disrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic. Trade is likely to play a crucial role in the mitigation of the impact of climate change since it ensures the availability of environment-friendly technology along with the movement of goods and services across borders.

- Initiative on policy design to tackle financial risks:

Strong macroprudential regulations, such as Basel III, that emerged after the global financial crisis of 2008-09, must be coupled with accounting practices to ensure that international standards are met without falling into the trap of a one-size fits policy design.

The G20 members must continue to support the evolution of financial architecture that reduces risks of collapse and prevents future financial turmoil. It may also be useful to consider the development of an early-warning system to ensure quick and adequate policy response to prevent future systemic collapse. In particular, the EMDEs are at the receiving end due to the transmission of financial shocks internationally, as they are subject to higher volatility. This is because EMDEs have less diversified financial products with lower market capitalisation than developed countries.

- Supply-side disruptions strengthening global supply chains:

The COVID-19 pandemic exposed various weaknesses in global supply chains, including logistics disruptions that affected the flow of goods, production delays due to staffing shortages, breakdown of raw material supply chains, and rising procurement prices. Investment in innovative technology that makes production processes flexible and resilient, and reduces cost, is the need of the hour. The ripple effect of global shocks may be absorbed in the future if seamless integration across global value chains is made possible. Global peace is a tall order, and we must strive to find solutions to supply-side bottlenecks, despite geopolitical conflicts in various parts of the world.

Therefore, it is crucial to build resilience and a swift response strategy to tackle the impact of severe recessions and financial turbulence resulting from external shocks. This can be created by focusing on early-warning systems and policies that mitigate vulnerabilities and augment resilience. Growth for the sake of growth is not good enough, as humanity must balance the inter-temporal and inter-generational costs of polluting and damaging the environment. The use of innovative and inclusive technology can bridge gaps on the supply side due to climate change-related disruptions in the growth and development process. Finally, policy responses must be tailored to the type of external shock and, in particular, macroeconomic policy responses to common shocks need to be coordinated.

Attribution: Pami Dua and Divya Tuteja, “Building Resilience to External Shocks in G20 Economies,” T20 Policy Brief, September 2023.

[a] The pandemic led to a recession in the US between February and April 2020.

[b] Such as China and India.

[c] According to the Economic Cycle Research Institute, China and India’s recession dates are December 2019 to March 2020 and February 2020 to April 2020, respectively. For more, see: Anirvan Banerji and Pami Dua, “The Increasing Synchronization of International Recessions,” in Macroeconometric Methods: Applications to the Indian Economy (Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore, 2023), 377–90.

[d] COVID-19 has led to the sharpest recession since the Great Depression of 1929.

[e] Macroeconomic trilemma states that it is not possible to have an independent monetary policy, stable exchange rate, and perfect capital mobility.

[1] Anirvan Banerji and Pami Dua, “The Increasing Synchronization of International Recessions,” in Macroeconometric Methods: Applications to the Indian Economy (Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore, 2023), 377–90.

[2] Anirvan Banerji and Pami Dua, “Synchronisation of Recessions in Major Developed and Emerging Economies,” Margin: The Journal of Applied Economic Research 4, no. 2 (2010): 197-223.

[3] Banerji and Dua, “The Increasing Synchronization of International Recessions”; Pami Dua and Divya Tuteja, “Synchronization in Cycles of China and India During Recent Crises: A Markov Switching Analysis,” Journal of Quantitative Economics 21, no. 2 (2023): 317–37.

[4] Dua and Tuteja, “Synchronization in Cycles of China and India During Recent Crises: A Markov Switching Analysis”.

[5] David C. Wheelock, “Comparing the COVID-19 Recession with the Great Depression,” Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, 2020, https://research.stlouisfed.org/publications/economic-synopses/2020/08/12/comparing-the-covid-19-recession-with-the-great-depression

[6] Scott R. Baker, Nicholas Bloom, and Steven J. Davis, “Measuring Economic Policy Uncertainty,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 131, no. 4 (2016): 1593-1636.

[7] Pami Dua and Divya Tuteja, “Global Recession and the Eurozone Debt Crisis,” Sustaining High Growth in India (2017): 177–214; Pami Dua and Divya Tuteja, “Impact of Eurozone Sovereign Debt Crisis on China and India,” The Singapore Economic Review 62, no. 05 (2017): 1137–64.

[8] Dua and Tuteja, “Global Recession and the Eurozone Debt Crisis”.

[9] Dua and Tuteja, “Impact of Eurozone Sovereign Debt Crisis on China and India”.