Task Force 2 Our Common Digital Future: Affordable, Accessible and Inclusive Digital Public Infrastructure

Abstract

Digital trade, including the cross-border supply of services, can be a game changer for developing G20 economies, which have yet to seize the full momentum of fast digitalisation. As different governance approaches to cross-border data flows (CBDF) co-exist, the significant information gap and the growing divergence in regulatory frameworks remain important obstacles to digital trade.

This policy brief examines existing national and international regulatory frameworks and recommends that G20 economies work on the design and establishment of a centralised Digital Regulation and Information Repository (DRIR) comprising information on regulatory arrangements and institutional frameworks governing CBDF in different jurisdictions. A DRIR will not only enhance transparency and information sharing, but serve as an avenue to build consensus towards a successful and inclusive regulatory framework. Further, it can be a valuable tool for future trade, digital agreements negotiations, and to inform economies of necessary policy and regulatory reforms.

1. The Challenge

In recent years, digital trade has emerged as a critical driver of economic growth and development worldwide, and Asia and the Pacific regions are no exception. The growth of digital trade has been fuelled by the widespread use of digital technologies, such as e-commerce platforms, social media, and cloud computing. These technologies have enabled firms to reach a global audience and have facilitated the exchange of digital products and services across borders.[1]

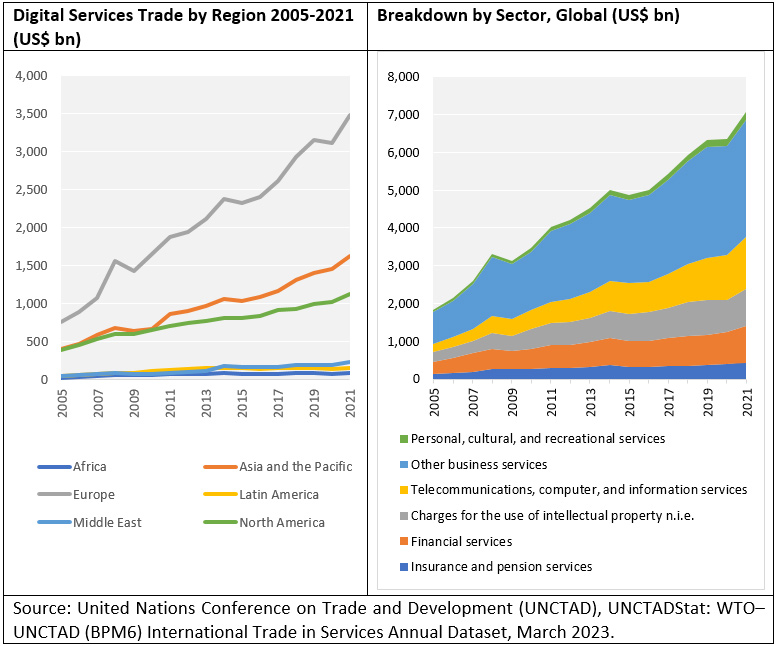

Figure 1: Trends in digital services trade (2005-2021)

Digital services trade, which encompasses all internationally traded services that are digitally ordered or delivered, is growing significantly.[a],[2] Between 2005 and 2021, trade in digital services globally almost quadrupled, rising from US$1.8 trillion to US$7.0 trillion (see Figure 1). Despite the pandemic, digital services trade demonstrated resilience, with a robust 11.4 percent global rebound in 2021. Europe, Asia, and the Pacific account for nearly 80 percent of the global digital services trade.

The ability to move data seamlessly across borders is critical for digital trade, particularly digital services trade,[3],[4] such as online education, telemedicine, and software development. Data flows enable firms to access global markets, collaborate with partners and suppliers, and offer customised services to customers worldwide.

However, data flow restrictions remain high and more prevalent in Asia. The proportion of data localisation measures by Asian economies is larger than the rest of the world, representing a share of around 70 percent. As for local storage requirements, Asia’s share is relatively small. Conditional flow regimes are a lot more common. Yet, the proportion of conditional flow regimes in Asia remains relatively modest compared to Europe and Latin America. [5]

Another layer of complexity is the heterogeneous nature of governance schemes and legal and regulatory environments across countries. The fragmentation of domestic regulations on data flows, the lack of shared information on national institutional mechanisms (such as the division of labour across line and support ministries and coordination)and uncertainty about practices for the application of digital trade rules constitute major obstacles to the development and adoption of consistent interoperable digital standards.[6]

Currently, data collection efforts by multilateral organisations and academic institutions are geared towards identifying shared interests in digital trade issues (for instance, the Digital Trade Inventory), mapping domestic regulations (such as the Digital Trade Integration Database), and culling digital trade-related legal provisions subsumed in trade agreements (the Trade Agreements Provisions on Electronic-commerce and Data, or TAPED, database).

Current initiatives monitoring cross-border data flow regulations

Several initiatives are now providing more granular information on digital regulations, including cross-border data flow (CBDF), improving to a great extent policymakers’ understanding of the digital regulatory landscape.[b] Three major initiatives in this regard are presented in Table 1.

Table 1: Overview of open-access databases on digital trade measures

| Digital Trade Inventory | Digital Trade Integration Database | Trade Agreements Provisions on Electronic-commerce and Data (TAPED) | |

| Host | Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development | European University Institute | University of Lucerne |

| Release date | Up to date as of October 2020 | October 2022 | July 2021. (Updated November 2022) |

| Coverage | 163 WTO members, 25 WTO observers, and 4 non-observers | 100 countries | Over 370 Preferential Trade Agreements concluded since 2000 |

| Measures | 12 broad policy areas, and 27 specific areas | 12 pillars with a total of 65 indicators | 5 pillars with a total of 114 commitments |

Digital Trade Inventory describes a range of rules, principles, and standards on digital trade for areas complementary to the WTO.[7] On the flow of information, the inventory tracks measures for cross-border transfer of information by electronic means, and local storage requirements, such as location of computing facilities and location of financial computing facilities. It also includes information on plurilateral agreements to foster data flows and ensure data privacy, including regional trade agreements containing provisions on CBDF and local storage requirements.[c]

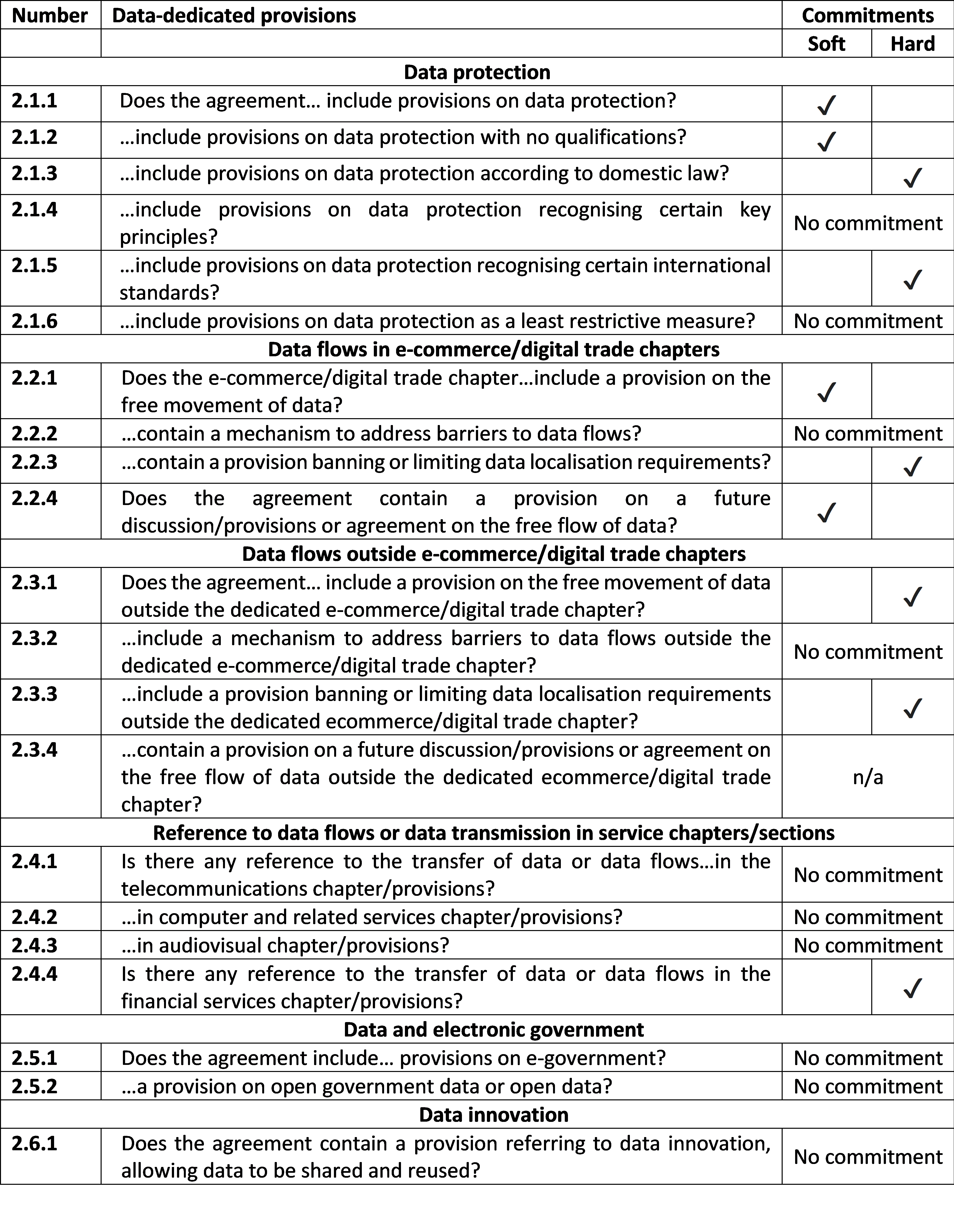

TAPED traces developments in digital trade governance.[8] In the area of data flows, it maps information in the e-commerce/digital trade chapter (and outside dedicated chapters) covering provisions on the free movement of data, mechanisms to address data flows barriers, the banning or limiting of data localisation requirements, and ongoing discussions on the free flow of data. Finally, TAPED maps any reference of data flows in the telecommunications, audiovisual, and financial services chapter/provisions.

The Digital Trade Integration Database is structured into 12 pillars, with a total of 65 indicators observed across 100 countries providing information on policies affecting digital trade integration.[9] Indicators on data flows are grouped into two pillars—cross-border data policies, and domestic data policies. The former includes bans on transfers, and local processing requirements, local storage requirements, infrastructure requirements, conditional flow regimes, and participation in trade agreements committing to open CBDF. Domestic data policies include frameworks for data protection, existence of a minimum period for data retention, requirements to perform impact assessments, requirements to engage data protection officers, and policies that allow the government to access personal data collected.

Key features

In general, small, open, and services-oriented economies show a more favourable policy environment to regional and global integration through freer data flows. In contrast, large economies are more restrictive.[10], [11] Rules on the storage, use, and transfer of data, content access, and domestic data processing show lower levels of integration and higher heterogeneity in large economies. Some of these features, based on information collected by the initiatives discussed above, are described below.

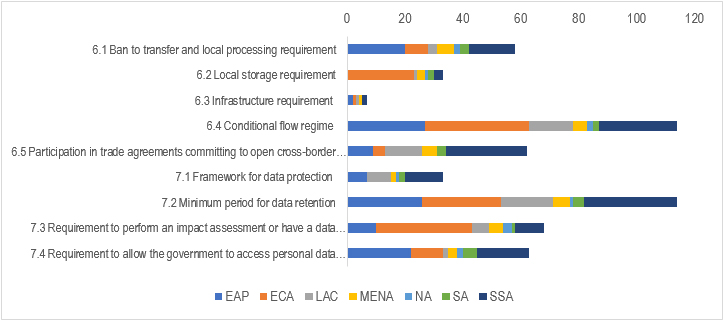

Figure 2. Digital trade measures concerning data flows, by geographical region of implementing country

Note: Geographical categories follow the classifications as identified in the Digital Trade Integration Database. EAP = East Asia and Pacific, ECA = Europe and Central Asia, LAC = Latin America and Caribbean, MENA = Middle East and Northern Africa, NA = North America, SA = South Asia, SSA = Sub-Saharan Africa.

Source: Computed from the Digital Trade Integration Database.

Regionally, economies from Sub-Saharan Africa implement 27 percent of all data flow measures covered in the dataset, closely followed by economies in Europe and Central Asia (26 percent) and East Asia and the Pacific (22 percent) (see Figure 2). Measures pertaining to participation in trade agreements committing to open CBDF (Indicator 6.5), framework for data protection (Indicator 7.1), and minimum period for data retention (Indicator 7.2) are mostly implemented by Sub-Saharan African economies. On the other hand, 70 percent of measures on local storage requirements (Indicator 6.2) and close to 50 percent of measures on requirements to perform an impact assessment or have a data protection officer (Indicator 7.3) are from European and Central Asian economies. East Asian and the Pacific economies have the most registered measures that ban transfers and require local processing (Indicator 6.1). The same economies also show a high number of measures allowing their governments to access personal data collected (Indicator 7.4).

International commitments through agreements and treaties

With the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) taking effect on 1 January 2022, provisions on ecommerce, which aim to promote electronic commerce among member economies, also came into force, aiming to build an ecosystem of trust in the use of e-commerce and enhance cooperation among stakeholders for its development.[12] This includes transmissions of data, information, and digital products over the internet or over private electronic networks. The TAPED database allows for a deeper assessment of digital trade commitments in preferential and regional trade agreements.

Table 2: RCEP commitments concerning data flows

Source: TAPED, November 2022 version.

The RCEP agreement comprises commitments pertaining to data protection, including binding commitments based on domestic laws and international standards (see Table 2).[13] The agreement also features commitments related to limiting data localisation requirements.[14] Annex 8A on ‘Financial Services’ and Article 9 on ‘Transfers of Information and Processing of Information’ enshrine commitments to free movement of data, while Article 12.14 on ‘Location of Computing Facilities’ prohibits any party from requiring a covered person to use or locate computing facilities in that party’s territory.[15] On the other hand, analysis from TAPED reveals the absence of provisions on enabling mechanisms to address barriers to data flows, e-government and open government data, and data innovation.

The Digital Trade Inventory can complement the analysis by providing information on other international instruments tackling digital trade commitments, including regional initiatives concerning data flows. The Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) Privacy Framework enlists cross-border privacy and cross-border transfer mechanisms in Sections III and IV, which recognise the importance of protecting privacy while maintaining the free flow of personal information across borders. In addition, APEC member economies have developed the Cross-Border Privacy Rules System, which provides “a means for organizations to transfer personal information across borders in a manner in which individuals may trust that the privacy of their personal information is protected”.[16] The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) Framework on Personal Data Protection , on the other hand, stipulates obtaining the consent of the individual for the overseas transfer of personal data or taking reasonable steps to ensure that the receiving organisation will protect the personal data consistently.[17] More recently, the ASEAN Agreement on Electronic Commerce, which entered into force in 2021, provides a set of policies, principles, and rules to govern cross-border e-commerce within the ASEAN.[18]

While these initiatives provide invaluable information on different countries’ regulatory stance with regard to their CBDF policy, they do not explore existing institutional arrangements and the adoption and implementation of digital trade policies. Such an effort will require a more coordinated approach to translate progress in regulatory compliance and adherence to international standards into de facto indicators of digital regulatory cooperation. CBDF regimes are having a clear impact on global economic activity and regulatory cooperation can bring multiple benefits. However, challenges to a common approach to CBDF continue to exist: domestic regulations are often non-coordinated, monitoring data protection measures is increasingly challenging, and comparability among domestic regulations cannot always be ensured. In addition, ensuring interoperability of domestic data regulations through international mechanisms, such as trade agreements, remains complex.[19] The need of the hour, therefore, is to build an adequate platform where problems of digital regulatory fragmentation can be addressed and finally overcome.

2. The G20’s Role

While freer flow of data fosters business activities and helps generate economic benefits, the emergence of giant digital platforms that are monopolising the collection, use, and sharing of personal data poses growing challenges to privacy and data security. The G20 is well-positioned to take a leadership role in promoting the free flow of data while balancing the need for privacy and security. In 2019, the G20 adopted a set of principles, the Data Free Flow with Trust (DFFT), to encourage the free flow of data across borders.[20] In 2022, the G20 Bali’s Declaration emphasised the members’ commitment to further enable data free flow with trust and promote CBDF.[21]

In 2023, the G20 Digital Economy Working Group will emphasise the development of open solutions, protocols, standards, and principles that are safe and accessible. The group will work towards the production of a Global Digital Public Infrastructure Repository, a toolkit for cyber education and awareness, and a resource for upskilling and reskilling programmes pertaining to digital skills.

Further, the G20 can create viable opportunities for promoting greater transparency and convergence of regulatory frameworks on CBDF. This could be achieved by creating coordinated mechanisms for the adoption and monitoring of domestic data regulations, as detailed further in the next section. The G20 can also play a vital role in providing technical and financial assistance to developing and emerging economies to help them identify and address gaps in the domestic regulatory framework and institutional arrangements.

3. Recommendations to the G20

While the DFFT principles represent a step forward in promoting the free flow of data, they lack concrete implementation mechanisms and are not legally binding. A comprehensive data system that links all areas of digital-economy participation, including information on institutional arrangements and implementation of digital trade regulations, will substantially help in formulating and evaluating different economies’ digital trade strategies. Additionally, it will help in identifying the technical assistance needed to narrow the digital divide among developing and emerging economies. As economies seek regulatory convergence to facilitate CBDF while securing national priorities, outlining how international commitments are translated into domestic laws or regulations (and vice versa) is important.

To help reconcile domestic regulations with international commitments on CBDF, the authors recommend the G20 economies work on the design and establishment of a centralised Digital Regulation and Information Repository (DRIR) comprising information on practices, degree of implementation, and institutional arrangements governing CBDF in different jurisdictions.

The DRIR will be a valuable tool to provide a common ground for future trade and digital agreements negotiations, informing economies of the necessary policy and regulatory reforms to be undertaken domestically to meet international commitments. It will also be able to offer institutional options for implementation practices, while fostering mutual recognition of different systems.

More specifically, G20 economies could consider the following steps:

Establish comprehensive mapping and collection of data on national legislation, regulations, and international commitments

- Review, consolidate, and complete existing mappings of national and international regulations on CBDF in G20 economies. This entails conducting a comparative analysis to harmonise existing methodologies and ensure comparability among reporting economies; designing and reviewing a consolidated ‘checklist’ of commitments and identifying potential missing dimensions (for example, enforcement mechanisms) or needs for refinements.

- Review and/or propose possible enforcement mechanisms: Enforcement mechanisms may involve different mechanisms at the domestic level (laws, statutes, rules, and administrative regulations) and at the international level (decisions and recommendations). Information on the binding or non-binding nature of the commitments and associated enforcement mechanisms (for example, through a dispute settlement system) could provide insights on the depth, credibility, and implementation of the commitments. Specific information about safeguards (or exceptions) from specific economies should be included to gauge the scope and timeline to adopt international commitments.

- Design a standardised and user-friendly template (based on the consolidated ‘checklist’ of commitments) for data collection on CBDF regulations, policies, and international commitments.

Analyse the degree of implementation, gaps, and constraints to the institutional framework faced by G20 economies

- Establish a measurement criterion to evaluate the degree of implementation of exiting national policies, and the gap between domestic practices and international commitments.

- Based on the criteria defined to evaluate the degree of implementation of exiting national policies, support the G20 economies in conducting surveys and consultations with stakeholders, such as businesses, government officials, and civil society organisations. Surveys can be used to gather quantitative data, while consultations can provide qualitative information on specific implementation challenges and opportunities.

- Collect quantitative and qualitative information on regulatory reform regarding CBDF based on: Input indicators (factors such as budget for regulatory policy and oversight, staff involved in regulatory policy, and training), and output indicators (such as of regulatory performance like laws and subordinate regulations and administrative burdens).

- Design a standardised reporting template on the degree of implementation, practices, and institutional framework of cross-border data flows. Organise intergovernmental and multistakeholder consultations with policymakers, regulatory agencies, and private sector agents to discuss the key entries to be reported to the DRIR based on initial findings from previous steps. This includes sector of activities, leading regulatory agencies’ names, mandate, size, organisational structure, focal point for implementation of CBDF policies, and regulations; and concrete steps to be undertaken to align domestic policies with international commitments, including timeline, leading agency, national stakeholder, and external development partners involved (if any).

- Raising awareness and providing technical and financial assistance to G20 economies to understand the template, collect relevant information, and report the data to the DRIR.

- Conduct research on data collected to identify best practices and needs for technical assistance in priority areas[d] for the implementation of cross-border data flow regulations. Possible areas include impact of domestic regulations and international standards in prompting digital (services) trade, digital regulatory convergence, and economic spillovers.

Attribution: Pramila Crivelli, Rolando Avendano, and Jong Woo Kang, “Building an Information-Sharing Mechanism to Boost Regulatory Frameworks on Cross-Border Data Flows,” T20 Policy Brief, May 2023.

Endnotes

[a] For more details on the definition of digital services trade see ADB’s Unlocking the Potential of Digital Services Trade in Asia and the Pacific (endnote 1) and OECD-WTO-IMF’s Handbook on Measuring Digital Trade (endnote 2).

[b] Previous initiatives have developed similar inventories on regulatory developments on digital trade. See, for example, the Digital Policy Alert by the St. Gallen Endowment, and Digital Trade Estimates Project by ECIPE.

[c] Examples include the OECD Guidelines on the Protection of Privacy and Transborder Flows of Personal Data, APEC Cross-border Privacy Rules, ASEAN PDP framework.

[d] Priority areas could be identified and classified based on the expected time needed to implement the regulations and the associated needs for technical assistance, learning lessons from the Trade Facilitation Agreement categories A, B, and C.

[1]. Asian Development Bank, Unlocking the Potential of Digital Services Trade in Asia and the Pacific, November 2022 (Manila: Asian Development Bank, 2022).

[2]. OECD-WTO-IMF, Handbook on Measuring Digital Trade, Version 1 (Paris: OECD Publishing, 2020).

[3]. Asian Development Bank, Asian Economic Integration Report 2022: Advancing Digital Services Trade in Asia and the Pacific, February 2022 (Manila: Asian Development Bank, 2022).

[4]. United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, Digital Economy Report 2021: Cross-border data flows and development: For whom the data flow, September 2021 (New Yok: United Nations Publications 2021).

[5]. Asian Development Bank, Asian Economic Integration Report 2022: Advancing Digital Services Trade in Asia and the Pacific, February 2022 (Manila: Asian Development Bank, 2022).

[6]. International Telecommunication Union, Global Cybersecurity Index 2020: Measuring commitment to cybersecurity, June 2021 (Geneva: 2021).

[7]. Taku Nemoto and Javier López González, Digital trade inventory: Rules, standards and principles, June 2021 (Paris: OECD Publishing, 2021).

[8]. Mira Burri, Maria Vasquez Callo-Müller, and Kholofelo Kugler. TAPED: Trade Agreement Provisions on Electronic Commerce and Data, November 30, 2022, published by University of Lucerne.

[9]. Martina Ferracane, Digital Trade Integration Database, 2022, European University Institute.

[10]. Simon Evenett and Johannes Fritz, Emergent Digital Fragmentation: The Perils of Unilateralism, June 2022 (London: Centre for Economic Policy Research, 2022).

[11]. Martina Ferracane, Digital Trade Integration: Global Trends, September 2022 (Brussels: Trans European Policy Studies Association, 2022).

[12]. Asian Development Bank, The Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement: A New Paradigm in Asian Regional Cooperation?, May 2022, (Manila: Asian Development Bank, 2022).

[13]. “Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement”.

[14]. Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement.

[15]. Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement.

[16]. “Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation Privacy Framework”.

[17]. “Association of Southeast Asian Nations Framework on Personal Data Protection” .

[18]. “Association of Southeast Asian Nations Agreement on Electronic Commerce”.

[19]. World Economic Forum, From Fragmentation to Coordination: The Case for an Institutional Mechanism for Cross-Border Data Flows, April 2023 (Geneva: World Economic Forum, 2023).

[20]. G20, “G20 Ministerial Statement on Trade and Digital Economy,” June 9, 2019.

[21]. G20, “G20 Bali Leaders’ Declaration,” November 16, 2022.