Task Force 6: Accelerating SDGs: Exploring New Pathways to the 2030 Agenda

Gender equality is both a global goal in its own right and a required input to remedy the current ‘pluri-crises’ and accelerate progress towards the 2030 Agenda. Advancing gender equality, however, necessitates not only addressing gender gaps but also underlying systemic and deeply embedded drivers. There are five potential pathways of action for the G20 that do so: equitable livelihoods and economic empowerment; equitable decision-making; integrated data systems and informed policy; secure and operationalised rights; and transformative change. More broadly, to ‘leave no one behind’ and be effective in building on the G20’s important commitments to date, policy and investments should include targeted consideration of how gender and social inequities interact and must keep pace with how the concept of gender is evolving in societies.

1. The Challenge

Gender and the SDGs

Gender[a] equality is embodied by Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 5, which aims to achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls. Equality is both an end and a means. It is “not only a fundamental human right, but a necessary foundation for a peaceful, prosperous and sustainable world.”[1]

Persistent gender inequalities hamper the progress of SDGs. For example, discrimination in land rights and property ownership negatively affects land and water resources management (SDG-14, SDG-15)[2] and undermines climate resilience (SDG-13).[3] Conversely, gender equality in economic opportunities reduces poverty (SDG-1)[4] and contributes to growth and food security (SDG-2);[5] gender-responsiveness in social protection contributes to these as well as educational outcomes (SDG-4).[6] Moreover, progress towards the SDGs is clearly gendered, including in terms of poverty (SDG-1),[7] food (SDG-2),[8] water, sanitation, and hygiene (SDG-6),[9] energy (SDG-7),[10] and climate (SDG-13).[11] Given this interdependence, if G20 nations do not effectively address gender inequities, the risk is not only to SDG-5 but to the entire 2030 Agenda.

G20 2023 is a critical moment to leverage recommitment to the 2030 Agenda’s core mission to ‘leave no one behind’. Based on learning from the COVID-19 pandemic and ongoing ‘pluri-crises’, policy dialogue and commitments need to be bolder and more nuanced than previous G20 events. This can be achieved through more consistent operationalisation of the G20’s commitments to equality and through addressing the underlying, interconnected gender, social, and historical drivers that underpin who is ‘left behind’.

Where things stand

Gender equality has been unravelling “in the face of ‘cascading’ global crises—such as the COVID-19 pandemic, conflict, and climate change—coupled with the backlash against women’s sexual and reproductive rights.”[12] While progress was already slow, the world is now further from equality than it was pre-pandemic.[13] On the current path, it will take 140 years to achieve gender equal representation in leadership positions in the workplace and 286 years to close gender gaps in legal protection and remove discriminatory laws against women.[14]

Moreover, gender and socioeconomic discriminations, barriers and exclusions intersect and compound (known as ‘intersectionality’). This leads to intensified marginalisation of women (and gender minorities) from indigenous or ethnic minority, migrant, or other groups, or those who are living with disabilities.

The urgency to address gender inequality is paramount in G20 countries; none of the 20 nations are on track to achieve SDG-5 by 2030.[15] Despite extensive commitments, gender- and interrelated social inequalities continue or have worsened, reflecting the persistence of historical, systemic power imbalances, and underlying challenges that need specific recognition and action.

Unpacking the challenges: Manifestations and drivers

Gender inequalities and inequities in and across G20 nations manifest in a multitude of ways. These include:

- the disproportionate amount of unpaid domestic and care work performed by women compared to men (which ranges from 1.5 times more in Canada, Germany, and US to nine times more in India[16]);

- exclusions from equitable livelihoods and incomes (women’s labour force participation for instance, is lower in every G20 country with data[17]);

- gendered gaps in financial access and information and communication technology (for instance, in G20 countries, women are less likely than men to have bank accounts, credit, or savings for a farm or business[18]);

- stereotypes regarding decision-making capacities (for example, 72 percent of the population in one G20 country indicated that “on the whole men make better political leaders than women”[19]); and

- persistently high rates of gender-based violence (GBV) in G20 countries (where more than one in four women have experienced intimate partner violence[20]), which undermines all areas of life, wellbeing, and economic prosperity, with intergenerational consequences.

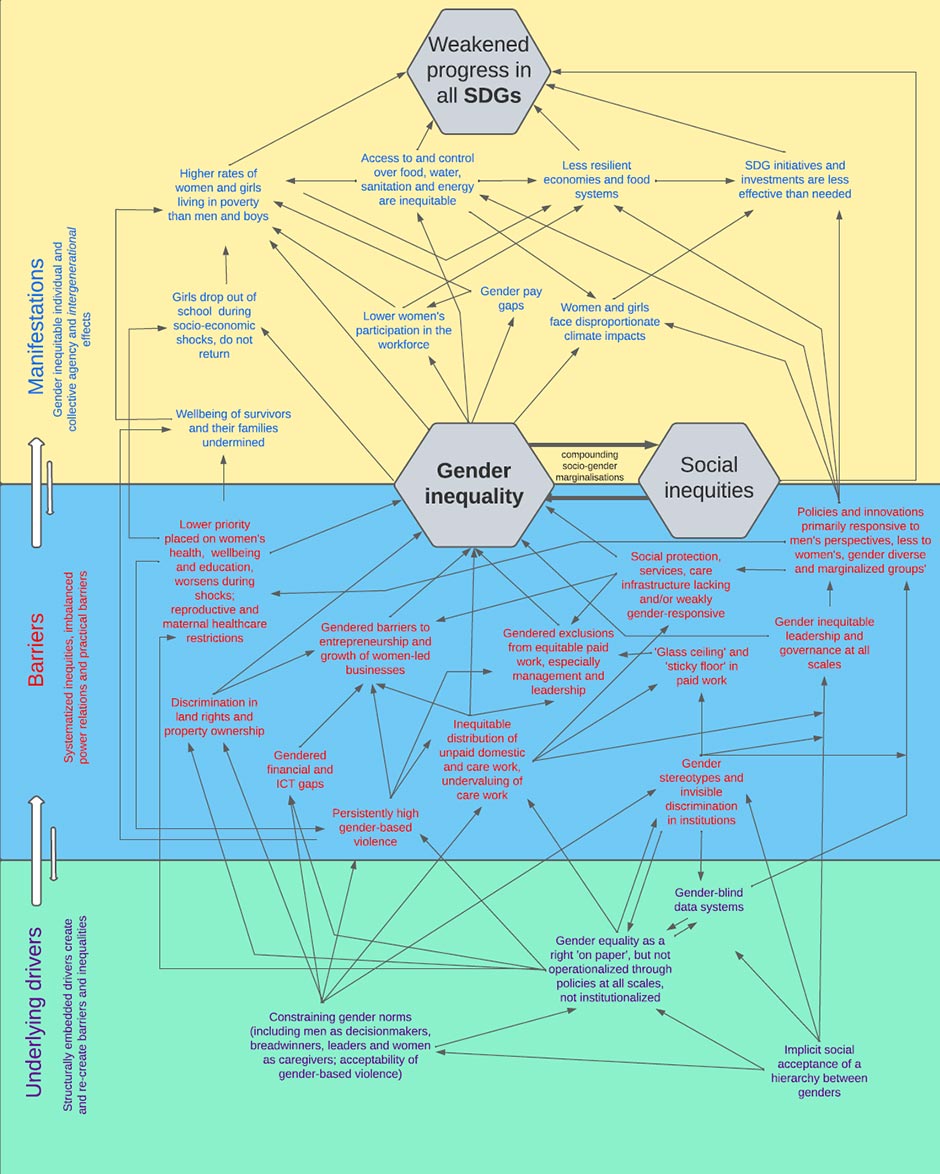

The evidence demonstrates that manifestations of inequality are perpetuated and entrenched by systematised barriers and deep, underlying drivers. These include formal (policy) and informal (gender norms and beliefs) drivers. Even when legal frameworks exist, these are often not effectively operationalised, reflecting the largely unnoticed informal ‘rules’ shaping society. Restrictive gender norms (social expectations regarding how women, girls, men, and boys should behave and roles they should play in society) and implicit assumptions regarding the value of different genders in society have profound effects. These reinforce an implicit hierarchy in which women and nonbinary people are less important or ‘correct’ than men—translating into them being less represented and served by institutions and systems[21]. These norms also rationalise GBV and entrench unhealthy patterns for men, and are so deeply embedded in daily life that they go unseen, appearing to be ‘the natural order’. This normalises who are seen as ‘real’ leaders, decisionmakers, and breadwinners versus who are made responsible for unpaid domestic and care work. Figure 1 visualises the layered nature of inequalities and deeper systemic and structural drivers.

Figure 1: Drivers, barriers, and manifestations of gender inequalities

Source: Authors’ own

2. The G20’s Role

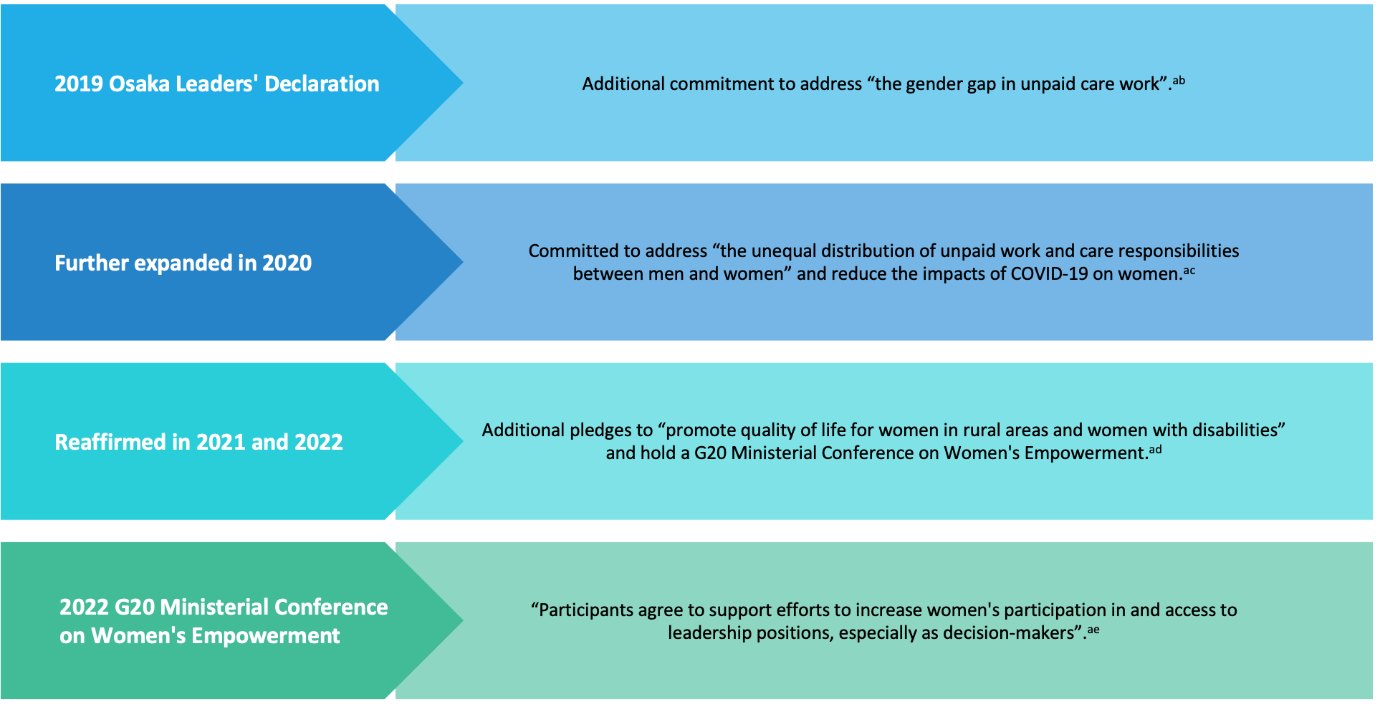

The G20 significantly influences economic and associated policies of member countries—notably those driving (or failing) SDGs. The G20 also sets the SDG ‘pace’ for non-G20 middle and low-income countries, including those which tend to progress even more slowly towards SDG-5 and gender equality. As such, it is significant to note that G20 2023 stands on a decade-strong foundation of commitments to gender justice (see Figure 2).

However, the G20 track record on implementing these commitments is weak, contributing to the slow progress and declines in equality; compared to 71 percent compliance for all issues, compliance for gender commitments averaged at only 62 percent.[22] Moreover, follow-through is inconsistent among G20 nations, which reduces the coherence and integrity of the G20 and weakens overall influence on advancing the SDGs.

Figure 2: G20 gender equality commitments (2012 to 2023)

Source: Authors’ own

3. Recommendations to the G20

To accelerate the SDGs, G20 policies and programmes need to address the manifestations of gender inequality. More fundamentally, G20 nations need to transform the underlying systemic causes and structural drivers of gender inequality. Outlined here are five evidence-based pathways for G20 action, each with specific recommendations.

Pathway 1: Equitable livelihoods and economic empowerment

Explicitly value unpaid care and domestic labour within G20 economies and set up incentives and systems to reduce inequitable unpaid work: Develop or enhance national/subnational accounting systems that better take into account the contribution of care and domestic work. Additionally, consistent investment in the care economy is required across all G20 nations. This includes affordable and quality childcare,[23] targeting single-parent households for social benefits (following Germany and Japan),[24] paid paternity leave (following Italy, Turkey),[25] and strengthened labour laws incentivising men’s participation in care work.[26]

Double down on the G20’s ‘25×25’ goal to reduce the gender gap in labour force participation by 25 percent by 2025 and its principles to improve the quality of women’s employment across all G20 nations: Address the substantial gender pay gap that continues in most G20 countries[27]. Invest consistently in policies and practices that break the ‘glass ceiling’ and ‘unstick’ the ‘sticky floor’ keeping women in lower-paid work such as removing identifiers in hiring processes,[28] consistently enforce non-discrimination and anti-harassment laws, continue investing in girls in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics,[29] fund and capacitate collective entry points, including women’s cooperatives and self-help groups,[30] and, mandate an equitable balance of women-owned businesses in public and corporate procurement.[31]

Leverage legal and programmatic options to end GBV[32]: Policy and programming that engage men and boys in breaking the GBV cycle are essential in investments for economic justice.[33] More broadly, public planning for safe, inclusive public transport and spaces is required for equitable labour force engagement, and to be effective, planning requires inputs from those it is meant to serve.[34],[35]

Engage with the informal sector and capitalise on pandemic innovations: Take immediate policy action based on lessons about ‘what works’ to support desirable aspects of informal work (e.g., flexibility), while reducing risks. This is especially important in relation to indigenous and young women who are disproportionately exposed to risks and inequities of informal work. Such policy actions would include protections for vulnerable workers (e.g., domestic workers in Argentina and the self‐employed in Italy), provisions to counter false subcontractors (e.g., in Türkiye), and insurance provisions for home‐workers (e.g., Indonesia).[36] Moreover, there is a need to capitalise on pandemic-inspired innovations, especially continuing to “strengthen, adapt and extend social protection systems to informal employment.”[37]

Protect rights and wellbeing of migrant workers of all genders both in transit and at their destinations: To advance justice and support economic outcomes, G20 leaders need to prioritise cooperation and enforcement to prevent illegal human trafficking and ensure full transparency and thus safety and wellbeing along migration routes. Dedicated national and cross-national task forces to identify and address gender-blind aspects of migration policies and programmes are important to address the distinct risks for women, girls, boys, men, and gender minorities who migrate.[38]

Pathway 2: Equitable decision-making

Secure gender-balanced representation in decision-making, including for climate policy and land and resource rights: Accelerate follow-through on representation targets within G20 nations, such as gender balance in elected and appointed positions. However, representation is not sufficient, as the relationship between numbers and substantive equity in decision-making is complex.[39] Complementary measures, including strengthening of processes, are essential to avoid backlash and move past token engagement.

Invest in capacity development for groups working to advance gender equality: Prioritise support for women’s and gender minorities’ opportunities and capacities to engage in local to national decision-making processes. Invest in multifaceted capacity development of civil society that is working to advance gender equality and rights, including in relation to climate and financing. Build capacities of public sector actors of all genders—specifically, convenors and facilitators of policy processes at all scales—to (co)design, support and act on inclusive processes.

Address underlying constraints and unrecognised hinderances in decision-making systems and processes: SDGs will accelerate when G20 nations can strengthen policy processes such that they enable fuller and more meaningful engagement with and of civil society organisations. Beyond better representation and capacities of marginalised groups to voice their needs and interests (above), success relies on policy actors and implementors more pro-actively and effectively recognising these groups as rights holders, adapting systems for equitable voice, and effectively incorporating and responding to inputs.[40],[41]

Pathway 3: Integrated data systems and informed policy

Break the ‘cycle of invisibility’ via data systems: G20 nations can demonstrate global leadership by accelerating the closing of pernicious gender data gaps. Global, national, and subnational statistical systems need to be assessed and updated to break the ‘cycle of invisibility’ (see Figure 3). Ensure that sex- or gender-disaggregated data are consistently generated—otherwise inequalities are masked.[42]

Figure 3: Cycle of invisibility

Source: Adapted from McDougall et al. 2021, 4.[43]

Review and upgrade sectoral and social policies to be more effectively and consistently gender-integrated: National and subnational G20 agencies can redress gender weaknesses in social protection systems, and climate and sectoral policies and programming. Nationally determined contributions are moving in the right direction, but more is needed in terms of gender capacity, clear targets, gender-disaggregated data, and routine engagement between environment, climate, and gender ministries and civil society.[44] Significantly more is needed for consistent, quality gender integration in sectoral and climate policies, moving from ‘add women and stir’ to ‘transformative’ (address underlying barriers) action.[45]

Catalyse more systematic national and subnational gender budgeting across the G20: Gender budgeting “recognizes that government budgets impact men and women differently.…[It] uses fiscal policies and public financial management tools to promote gender equality. It incorporates a gender lens into the budget process to ensure that governments are acutely aware of the impact of their choices on gender outcomes.”[46] This essential strategy needs to be consistently institutionalised and applied in G20 nations (see Figure 4).

Figure 4: Gaps in gender budgeting practice in G20 nations

Source: Adapted from Alonso-Albarran et al., 2021, 17

Pathway 4: Secure and operationalised rights

Build on the momentum of feminist foreign policy: Feminist policies are human-centred, based in respect for rights, and seek equality for all people. Sustainability as well as peace may depend on furthering these across G20 nations, as “trade and economic policies that are not feminist and not striving to pro-actively eradicate inequalities are likely to perpetuate injustice and consequently fuel conflict.”[47] Canada, Mexico, France, Germany, and Sweden have paved the way by being the first to adopt feminist foreign policy agendas. More broadly, the G20 can demonstrate leadership through evidence-based dialogue around the risks of conflating economic growth and social progress.[48]

Operationalise international commitments, including implementation of land rights and eradication of GBV: Immediate action is needed to consistently secure the rights of women and marginalised genders. This includes G20 nations evenly operationalising existing international commitments, such as the Convention on Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW). Focusing on GBV, the G20 should consider integrating its ‘25×25’ goal with collective strategies translating CEDAW commitment into action. G20 policy narratives recognising all SDGs as fundamentally intertwined with women’s rights—and more broadly human and environmental rights—will add needed fuel to SDG acceleration. Accordingly, governance, access to and control over services, food, water, and education can immediately be made more accountable (regarding rights) and gender equitable, to balance historic prioritisation of growth.[49]

Pathway 5: Transformative change

Complement but go beyond ‘business as usual’ mainstreaming and women’s empowerment; invest in a gender-transformative approach: Since gender inequalities persist in G20 nations due to systemic factors and underlying drivers, progress relies on operationalising a gender-transformative approach at all scales. Build on the evidence-based success of the United Nations and non-governmental organisations through investing in gender-transformative programming and strategies from local to national scales. Systematically address norm-related constraints (and unconscious bias, gender hierarchy) within government, private sector, and other organisations.[50]

Figure 5: Gender approaches

Note: Rather than working around barriers and focusing on empowering women, a transformative approach addresses underlying formal and informal drivers of inequality. As well as policy- and systems-change, it engages men and boys in shifting harmful norms, such as masculinities that drive GBV and underpin inequitable labour and decision-making.

Source: McDougall et al., 2021

To accelerate progress towards SDG-5—thus all SDGs—model men and boys as co-owners of the gender equality agenda: Include people of all genders, including men and boys as stakeholders of gender equality. This requires direct role modelling and accountability by men in leadership, as well as investing in programming to support this as a wider shift. G20 leaders’ role modelling this in G20 2023 is critical. The G20 should follow this through by inspiring and requiring co-ownership from national to local levels.

Attribution: Cynthia McDougall et al., “Beyond Gender Inequality: How the G20 can Support a Gender Equitable-Future and Accelerate the SDGs,” T20 Policy Brief, July 2023.

Endnotes

[a] Gender is broadly understood as socially constructed identities, roles, and power relations associated with being a man or woman. While gender identity was previously understood as binary in some contexts, it is now recognised in most G20 countries that gender identity is a multidimensional spectrum, including women, men, and an array of gender-diverse, nonbinary or ‘third’ identities. In Germany, Argentina, Mexico, Brazil, and Australia, up to 4 percent of individuals identify as neither women nor men, but as transgender, non-binary, gender-fluid, or non-conforming. Gender minorities face multiple additional barriers and discrimination, from legal identity to harassment and safety issues.

[1] “Goal 5: Achieve Gender Equality and Empower All Women and Girls,” Sustainable Development Goals, United Nations Sustainable Development, accessed January 15, 2023.

[2] Landesa, Women Gaining Ground: Securing Land Rights as a Critical Pillar of Climate Change Strategy, (Seattle: Landesa, 2017), 1.

[3] UN Women, “Why Gender Equality Matters across All SDGs,” in Turning Promises into Action: Gender Equality in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (New York: UN Women, 2018), 51–52.

[4] UN Women, “Why Gender Equality Matters, ” 8-10.

[5] UN Women, “Why Gender Equality Matters,” 11–12.

[6] UNICEF, Social Protection & Gender Equality Outcomes Across the Life-Course: A Synthesis of Recent Findings, (New York: UNICEF, 2021), 1-35.

[7] Ginette Azcona and Antra Bhatt, “Poverty Deepens for Women and Girls, According to Latest Projections,” UN Women/Women Count, February 1, 2022.

[8] FAO et al., The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2022, (Rome: FAO, 2022), 11.

[9] WHO and UNICEF, Progress on Drinking Water, Sanitation and Hygiene: 2017 Update and SDG Baselines, (Geneva: WHO, July 2017), 11.

[10] “Energy and Gender: A critical issue in energy sector employment and access to energy,” IEA, accessed March 31, 2023.

[11] Daisy Dunne, “Mapped: How Climate Change Disproportionately Affects Women’s Health,” Carbon Brief, October 29, 2020.

[12] UN,“Without investment, gender equality will take nearly 300 years: UN report,” UN News, September 7, 2022.

[13] World Economic Forum, Global Gender Gap Report 2022, (Cologny/Geneva: World Economic Forum, 2022), 5.

[14] UN, “Without investment,”.

[15] Kusum Kali Pal, “Gender Equality by 2030? Those Countries Making Most Progress Offer Lessons on What to Change,” World Economic Forum, September 21, 2022.

[16] OECD Development Centre, Ending Gender-Based Discrimination in G20 Countries: A Frame for Action, (Paris: OECD Development Centre, 2021), 13.

[17] OECD Development Centre, Ending Gender-Based Discrimination, 10.

[18] OECD Development Centre, Ending Gender-Based Discrimination, 20.

[19] OECD Development Centre, Ending Gender-Based Discrimination, 18.

[20] OECD Development Centre, Ending Gender-Based Discrimination , 28.

[21] Caroline Criado Perez, Invisible Women: Data Bias in a World Designed for Men, (New York: Abrams Press, 2019), 1-28.

[22] Julia Kulik, “G20 Performance on Gender Equality,” The Global Governance Project, n.d..

[23] OECD Development Centre, Ending Gender-Based Discrimination, 16.

[24] OECD Development Centre, Ending Gender-Based Discrimination, 17.

[25] OECD, “A Good Start for Equal Parenting: Paid Parental Leave,” in The Pursuit of Gender Equality: An Uphill Battle, (Paris: OECD, 2017), 199-206.

[26] OECD, “A Good Start,” 204.

[27] ILO and OECD, Women at Work in G20 countries: Progress and policy action, (Geneva: ILO, 2019), 3.

[28] WGEA, “Gender equitable recruitment and promotion,” Workplace Gender Equality Agency—Australian Government, 6 August, 2019.

[29] EIGE, “Economic Benefits of Gender Equality in the European Union,” EIGE Newroom, 2023.

[30] Thomas de Hoop et al., “Learning about Women’s Groups: The evidence from South Asia,” The World Bank, March 16, 2023.

[31] Barbara Orser et al., “Gender-Responsive Public Procurement: Strategies to Support Women-Owned Enterprises,” Journal of Public Procurement 21, no. 3 (January 1, 2021): 261.

[32] Mabel Bejarano Cobo, “Equitable Partnerships to Support Women’s Economic Empowerment & Combat Gender-Based Violence,” Global Communities, June 30, 2022.

[33] “Focusing on Prevention: Ending Violence against Women,” UN Women, accessed April 4, 2023.

[34] Criado Perez, Invisible Women, 1-28.

[35] Cassilde Muhoza, Anna Wikman, and Rocio Diaz-Chavez, Mainstreaming Gender in Urban Public Transport: Lessons from Nairobi, Kampala and Dar Es Salaam, (Nairobi: Stockholm Environment Institute, 2021), 4-29.

[36] ILO and OECD, Women at Work, 17.

[37] ILO, Building Back Better for Women: Women’s Dire Position in the Informal Economy, (Geneva: ILO, 2020), 9.

[38] UN Women, Policy Brief 4: Making Gender-Responsive Migration Laws, (New York: UN Women, 2017), 1.

[39] Sarah Childs, “The Complicated Relationship between Sex, Gender and the Substantive Representation of Women,” European Journal of Women’s Studies 13, no. 1 (February 1, 2006): 7.

[40] Valeria Esquivel and Caroline Sweetman, “Gender and the Sustainable Development Goals,” Gender and Development 24, no. 1 (January 2, 2016): 1-8.

[41] Suneeta Dhar, “Gender and Sustainable Development Goals,” Indian Journal of Gender Studies 25, no. 1 (February 1, 2018): 47-78.

[42] FAO, Towards gender-equitable small-scale fisheries governance and development, (Rome: FAO, 2017), 5.

[43] Cynthia McDougall et al., Gender Integration and Intersectionality in Food Systems Research for Development: A Guidance Note, (Penang, Malaysia: WorldFish, 2021), 4.

[44] “Advancing gender equality in NDCs: progress and higher ambitions,” UNDP Data Futures Platform, accessed May 24, 2023.

[45] Sarah Lawless et al., “Tinker, tailor or transform: Gender equality amidst social-ecological change,” Global Environmental Change 72, (January 2022),9-13.

[46] Virginia Alonso-Albarran et al., Gender Budgeting in G20 Countries: Working Paper 2021/269, (Washington, DC: IMF, 2021), 5.

[47] Nina Bernarding and Kristina Lunz, Feminist Foreign Policy for the European Union, (London: Centre for Feminist Foreign Policy, June 2020), 13.

[48] Valeria Esquivel, “Power and the Sustainable Development Goals: A Feminist Analysis,” Gender & Development 24, no. 1 (January 2, 2016): 9–23.

[49] Gabriele Koehler, “Tapping the Sustainable Development Goals for Progressive Gender Equity and Equality Policy?,” Gender & Development 24, no. 1 (January 2, 2016): 53–68.

[50] Cynthia McDougall et al., Fostering gender-transformative change for equality in food systems: a review of methods and strategies at multiple levels, (Nairobi, Kenya: CGIAR GENDER Impact Platform, In press), 67.