Task Force 4 – Refuelling Growth: Clean Energy and Green Transitions

There is an urgent need to simultaneously fulfil the targets of the Paris Agreement and Sustainable Development Goals. Various synergies exist between these agendas, and many energy transition policies focus on these co-benefits. There are, however, also difficult trade-offs that need to be managed to maximise the opportunities of transition. Given that many energy transition initiatives will take place in the G20 member countries, managing these trade-offs and ensuring a just transition is relevant for the grouping. Also, the G20, as a political forum and agenda setter, can influence global energy transition in ways that trade-offs are managed, and the climate agenda is optimally pursued. As just transition and sustainability are inherently about reducing inequalities, trade-offs should be looked at from an inequality perspective. The primary recommendation is for the G20 to build just transition partnerships that integrate management of inequality related trade-offs.

1. The Challenge

In 2015, the Paris Agreement and Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) were adopted, and the International Labour Organization produced a definitive model of a just transition.[1] Multiple co-benefits and synergies operate between the SDGs (such as SDG 7, or energy access) and the process of transitioning to a low carbon economy, , which is the basis of many countries’ co-benefits strategy.[2] There also exist, however, difficult trade-offs between energy transition and development, with negative impacts on the poor and the vulnerable.[3] As most studies focus on the quantity of synergies and trade-offs, the dominant argument is that synergies outweigh trade-offs,[4] and that policy instruments are needed to maximise these co-benefits.[5] Therefore, the focus on understanding and managing trade-offs is less. This is a narrow approach since the quality of trade-offs also need to be addressed, especially in developing countries.[6] Taking into consideration the national circumstances of each country and their priorities in adopting climate goals, in a way, helps them avoid conflicts between climate and domestic goals at the national level but these are not integrated at the local level. These trade-offs are not a reason to delay decarbonisation. Moreover, climate action needs to be ‘ratcheted up’. In view of these conditions, it becomes crucial to understand and minimise these trade-offs.

The concept of just transition addresses many of these trade-offs, and developing countries specifically are working towards making the energy transition ‘just’ and ‘inclusive.’ Just transition can be defined as moving towards a post-carbon society in a way that is fair and equitable with respect to registers of socioeconomic justice such as income, gender, and ethnicity.[7] Owing to the efforts of the international trade unions and labour organisations, the concept has evolved over the years and has also been incorporated in the climate negotiations of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). The official text of the Paris Agreement also mentions just transition as: “taking into account the imperatives of a just transition of the workforce and creation of decent work and quality jobs in accordance with nationally defined development priorities.”[8]

Many counties have tried to incorporate just transition in their Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) and energy transition policies. The existing frameworks on just transition consider SDGs to some extent, such as employment and gender targets, but are still limited. [9] Additionally, the engagement with inequality, which is a core dimension of both just transition and sustainability, is also limited. The inequality implications and social impact of any climate mitigation policy should be considered.[10] To ensure a just transition, it is then important to understand the trade-offs from an inequality perspective.

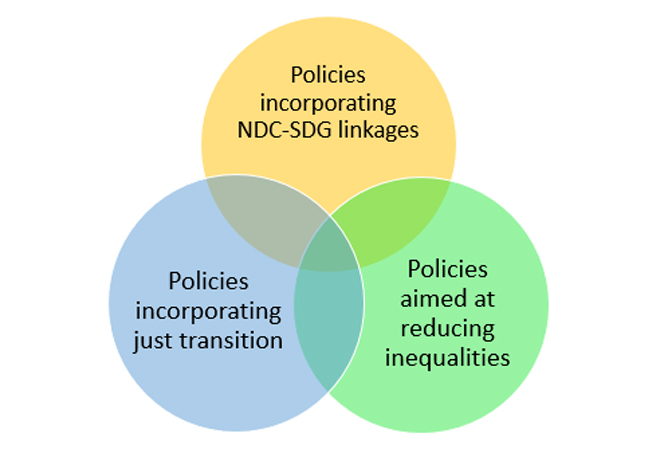

The challenge is that climate mitigation policies, including NDCs and domestic climate policies, incorporating climate-SDG linkages focus primarily on synergies and less on trade-offs. Another set of energy transition policies that incorporate just transition addresses some of these trade-offs but focuses majorly on employment and workforce and does not address other SDGs. Additionally, the policies, including the development policies of countries, aimed at reducing inequalities are treated as separate and isolated entities, focussing on various inequalities associated with education, income, health, and gender. The climate mitigation policies or energy transition policies do not consider the impact of inequality on other SDGs. This is a significant policy challenge that needs to be tackled to minimise the trade-offs and maximise the opportunities of energy transition. Policies aimed at just energy transition, SDGs, and efforts to reduce inequalities, despite interlinkages between them, are often treated as separate and not integrated as one agenda.

Figure 1: Policy challenges to a just transition

Source: Author’s compilation based on Markkanen and Kraavi [11]

2. The G20’s Role

The relevance of the G20 is threefold.

First, G20 countries play a critical role in the implementation of climate and development goals as they account for more than 66 percent of the world’s population, 85 percent of the global GDP, 80 percent of the world’s total primary energy consumption, and 82 percent of global energy-related CO2 emissions.[12] In addition to this, there is a lot of diversity in the G20 region, including developed countries with high energy demand and emissions on the one hand, and countries facing the need for urgent energy transition on the other hand. Energy access however is still a challenge for the developing member countries of the G20 and they will have to ensure energy transition while managing their development challenges. Therefore, it becomes crucial for the G20 countries to manage the trade-offs between energy transition and SDGs and to ensure a just and inclusive energy transition by integrating the climate and development agenda.

Second, the G20 already has just transition on the agenda. For instance, many presidencies have engaged with energy transition, specifically the Italian presidency[13] and the Indonesian presidency[14], where roadmaps for energy transition were also adopted.[15] In addition to this, many G20 countries, such as South Africa have even incorporated the concept in their NDCs. As far as the SDGs are concerned, the G20 has taken many actions to advance the 2030 Agenda.[16] Therefore, it becomes crucial for the G20 to manage the SDG related trade-offs associated with low-carbon transition.

Third, G20 as a forum can act as agenda setters and should govern the energy transition. A global energy transition can be advanced towards clean energy through international cooperation.[17] Since the bulk of the energy transition initiatives will take place in the G20, it can act as a role model and push the agenda for integrating policies on climate action, SDGs, and inequality.

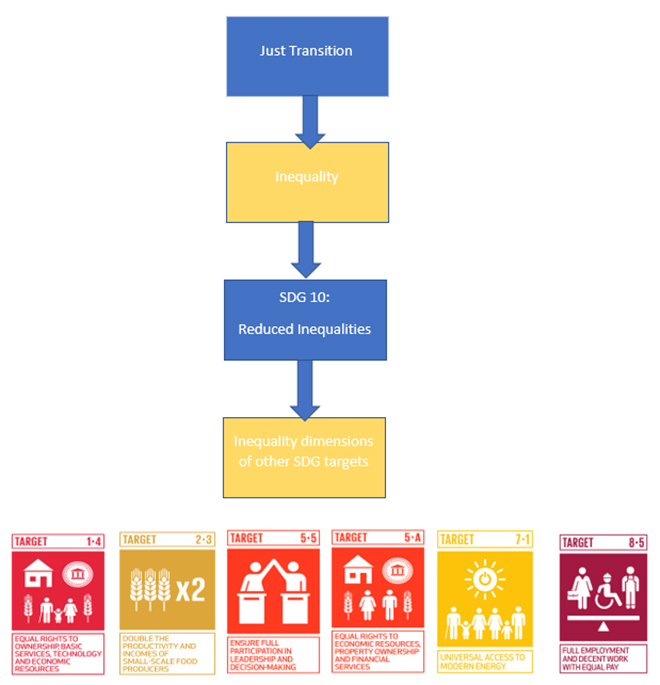

It is crucial for the G20 to undergo energy transition and in that process, there will be some difficult trade-offs with the SDGs which need to be managed. It is also difficult to decide which trade-offs should be given priority to ensure a just transition. Inequality is a core dimension of both just transition and SDGs, and can be taken as an entry point to study trade-offs between the two. This is because a just climate policy should ideally reduce existing inequalities[18]and in turn the lowered inequalities will further increase the effectiveness of the policy.[19] Reducing inequalities will also play an important role in achieving sustainability.[20] The SDG 10 incorporates a specific goal to reduce inequality. Every SDG however aims at addressing some or the other form of inequality.[21] This is because reduced inequalities can help in achieving economic growth and eradicating poverty, which are important sustainability goals.[22] Additionally, a fair and fast transition can also help in the achievement of several SDGs.[23]

Inequality can be used as a filter to select those SDGs whose inequality dimensions are most relevant to the question of low carbon transition and to construct a framework. SDG 10 is the most explicit linkage connecting just transition to SDGs. In the context of energy transition, managing the inequality dimensions of SDG 1 (no poverty), SDG 2 (zero hunger), SDG 5 (gender equality), SDG 7 (affordable and clean energy), and SDG 8 (decent work and economic growth) are the most relevant (see Figure 2). Any transition policy can reduce, reproduce, or exacerbate existing inequalities and a Just Transition-Inequality-SDG Framework can help in understanding these inequality implications. Such a framework can be used to both analyse existing policies as well as design better energy transition policies that are just and also integrate SDGs. Arguably, for any energy transition policy to be considered just should also aim at reducing inequalities.

Figure 2: Illustrative mapping of SDGs through an inequality lens

Source: Author’s compilation based on various sources[24]

3. Recommendations to the G20

Form global partnerships within and outside G20 with a focus on reducing inequalities and enhancing capabilities of developing countries to ensure a just transition

Firstly, the G20, through a pact or convention, should recognise the need for support-based partnerships to raise capacities of developing countries. Further, the developed countries within the G20 should form partnerships with the developing countries to help them with technological and financial resources, aimed at not only energy transition but also to help manage the inequality related trade-offs associated with the transition. The major aim of these partnerships should be to enhance capability of the developing countries by providing them with resources or capabilities needed to reduce inequality implications associated with a low-carbon transition. To make this partnership effective, first, a step wise analysis should be done to identify the trade-offs between energy transition and SDGs, using a Just Transition-Inequality-SDG framework, that are most relevant for the specific country. Further, the resources needed to manage these trade-offs should be identified, which can then be mobilised. The G20 can also use this approach to refine its existing just transition partnerships.

This recommendation is even more relevant in the context of the goals of India’s G20 presidency and the G20 Troika +1 (Indonesia, the 2022 chair, to South Africa, the 2025 chair) as it will provide a greater voice to the developing nations to articulate their concerns and form a consensus to build support-based partnerships.[25]

Enhance interaction within working groups to integrate linkages between just transition and SDGs

The different working groups of the G20 should collaborate and interact to identify the interlinkages between them. Further, the existing working groups should incorporate these interlinkages within their respective agendas. For example, the Energy Transition Working Group (ETWG) is a major entity focussing on energy transition, but it should also take inputs from other relevant working groups. The Employment Working Group (EWG), for instance, addresses many issues that are relevant for just transition but does not incorporate this essential linkage within their specific agenda. Further, the Development Working Group (DWG) and the Climate Sustainability Working Group (CSWG) work towards G20’s sustainable development agenda and climate agenda respectively. Since a major policy challenge is that these agendas are often treated as separate and unrelated, it is strongly recommended for the G20 to address and work on interlinkages between these agendas to manage trade-offs. The cooperation between ETWG, EWG, DWG, and CSWG should increase to identify interconnections, mainly trade-offs. In addition to this, the sherpa working groups should also interact with the finance working groups for a more holistic understanding, which will help in managing difficult trade-offs.

For the first time, the Sustainable Finance Working Group has added finance for SDGs to its agenda, setting up an example of why it is relevant to integrate the linkages between energy transition and SDGs for better mobilisation and utilisation of finance. Further, the G20 Engagement Groups play an important role and different groups should interact with each other and with other working groups. For example, the Labour20 directly addresses just transition concerns and should interact with the working groups for a more holistic understanding. Similarly, the Think20 group should also recognise and present just transition-SDG interlinkages to the relevant working groups.

As a mechanism to enhance these interactions, the G20, in addition to holding specific group meetings, should meet on a specific theme and invite representatives from all the working and engagement groups to present their input.

Integrate the linkages between just transition, inequality, and SDGs in member countries’ NDCs

As NDCs are important documents highlighting countries’ national circumstances and climate commitments, it is important to integrate linkages between just transition, inequality, and SDGs in this official document. As the majority of just energy transition initiatives will be implemented in the G20 countries, it is crucial for the G20 to take the lead and govern this shift.[26] Some G20 countries, like Canada and South Africa, have very well incorporated the concept of just transition but the linkages with SDGs are not established explicitly. Similarly, some of the NDCs have mentioned equity principles and job creation which is essentially just transition but have not made any overt engagement with these linkages. Just transition, inequality, and SDGs therefore are mentioned separately without mention of the linkages between them. As the NDCs need to be ‘ratcheted up’, it is crucial to integrate just transition and SDG linkages in the NDCs itself for an effective implementation of the climate agenda.

Guide financial investments towards a people-centric transition by developing specific guidelines

The G20, as a political forum, should utilise its engagement with the MDBs and other financial institutions to guide investments towards an ‘equitable’, ‘inclusive’, and ‘people-centric’ energy transition. This is in line with the G20’s work to strengthen and evolve the MDBs.[27] The G20 should further guide the MDBs towards investing in energy transition that also integrate the people-centric SDGs, with its main focus on reducing inequalities. This can be done by developing clear criteria and guidelines of investment, which are based on addressing the trade-offs associated with a just transition from an inequality perspective.

Attribution: Bhavya Jyoti Batra, “Addressing Trade-offs Between Energy Transitions and SDGs through G20 Partnerships: An ‘Inequality’ Perspective,” T20 Policy Brief, July 2023.

Endnotes

[1] International Labour Organization (ILO), Guidelines for a just transition towards environmentally sustainable economies and societies for all, February 2016, Geneva, ILO, 2015.

[2] Tara Caetano, Harald Winkler, and Joanna Depledge, “Towards zero carbon and zero poverty: integrating national climate change mitigation and sustainable development goals,” Climate Policy 20, no. 7 (2020): 773-778.

[3] Benjamin K Sovacool, “Who are the victims of low-carbon transitions? Towards a political ecology of climate change mitigation,” Energy Research & Social Science 73 (2021): 101916.

[4] David L McCollum et al.,”Connecting the sustainable development goals by their energy inter-linkages,” Environmental Research Letters 13, no. 3 (2018): 033006, 10.1088/1748-9326/aaafe3

[5] Gabriela Ileana Iacobuţă et al., “Transitioning to low-carbon economies under the 2030 agenda: Minimizing trade-offs and enhancing co-benefits of climate-change action for the sdgs,” Sustainability 13, no. 19 (2021): 10774.

[6] Ying Zhang and Mou Wang, “Climate change actions and just transition,” Chinese Journal of Urban and Environmental Studies 6, no. 4 (2018): 1850024.

[7] Darren McCauley and Raphael Heffron, “Just transition: Integrating climate, energy and environmental justice,” Energy Policy 119 (2018): 1-7.

[8] “Paris Agreement”, United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, United Nations, 2015.

[9] International Labour Organization, Just transition: an essential pathway to achieving gender equality and social justice, April 2022, Geneva, ILO, 2022.

[10] Sanna Markkanen and Annela Anger-Kraavi, “Social impacts of climate change mitigation policies and their implications for inequality,” Climate Policy 19, no. 7 (2019): 827-844.

[11] Markkanen and Kraavi, “Social impacts of climate change mitigation policies and their implications for inequality,” 827-844

[12] International Energy Agency and International Renewable Energy Agency, Perspectives for the energy transition investment needs for a low-carbon energy system, March 2017, Bonn, IEA and IRENA, 2017.

[13] G20 Italia, G20 Rome Leaders’ Declaration, November 2021, Rome, G20, 2021.

[14] G20 Indonesia, G20 Bali Leaders’ Declaration, November 2022, Bali, G20, 2022.

[15] G20 Indonesia, Decade of Actions: Bali Energy Transitions Roadmap, September 2022, Bali, G20, 2022.

[16] Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development and United Nations Development Programme, G20 contribution to the 2030 Agenda: Progress and Way Forward, September 2019, Paris, OECD and UNDP, 2019.

[17] Rainer Quitzow et al., “Advancing a global transition to clean energy–the role of international cooperation,” Economics 13, no. 1 (2019).

[18] Irina Velicu, and Stefania Barca, “The Just Transition and its work of inequality,” Sustainability: Science, Practice and Policy 16, no. 1 (2020): 263-273.

[19] Narasimha D Rao, and Jihoon Min, “Less global inequality can improve climate outcomes,” Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change 9, no. 2 (2018): e513.

[20] Nicholas A Ashford et al., “Addressing inequality: the first step beyond COVID-19 and towards sustainability,” Sustainability 12, no. 13 (2020): 5404.

[21] Katja Freistein, and Bettina Mahlert, “The potential for tackling inequality in the Sustainable Development Goals,” Third World Quarterly 37, no. 12 (2016): 2139-2155.

[22] Chiara Mariotti, The Role of the UK in Tackling Global Inequality: Contributions to achieving SDG 10, June 2019, United Kingdom, Oxfam GB, 2019.

[23] Climate Action Network (CAN), “Just Transition”, G20 Issue Brief, May 2018.

[24] Ramona Haegele, Gabriela I. Iacobuţă, and James Tops, “Addressing climate goals and the SDGs through a just energy transition? Empirical evidence from Germany and South Africa,” Journal of Integrative Environmental Sciences 19, no. 1 (2022): 85-120.; International Labour Organization, Advancing a Just Transition and the Creation of Green Jobs for All for Ambitious Climate Action, Geneva, ILO, 2019.

[26] Andreas Goldthau, “The G20 must govern the shift to low-carbon energy,” Nature 546, no. 7657 (2017): 203-205.

[27] G20 India, G20 Chair’s Summary and Outcome Document: First G20 Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors Meeting, February 2023, Bengaluru, G20, 2023.