TF-6: Accelerating SDGs: Exploring New Pathways to the 2030 Agenda

Road trauma is the largest killer of young people worldwide, and more than 100,000 people are killed or injured on the world’s roads each day. Significantly, road injury prevention has been included in the Sustainable Development Goals. The global mandate to improve road safety is especially critical for the G20 countries, which account for 59 percent of global road traffic fatalities and include some of the world’s best and worst performing countries. A lack of application of minimum safety standards for vehicles and roads contribute greatly to road trauma and many G20 countries are still far from best practice. It is recommended that the G20 countries implement minimum safety regulations for all new and used vehicles and new and existing roads and infrastructure according to the recommendations articulated in the United Nations Global Road Safety Performance Targets and the Global Plan for the Decade of Action for Road Safety 2021-2030.

1. The Challenge

Road trauma is a predictable and preventable humanitarian crisis. Tragically, road traffic injuries are reaching crisis proportions globally and over 1.35 million people die, while many millions more are seriously injured every year.[1] Inequalities can be seen between different world regions with a death rate 3 times higher in low-income countries compared to high income countries. Over the years, road trauma has made its way into 8th place as the leading cause of death globally and is the largest killer of those aged between 10 and 24 years old.[2]

Despite this, road injury prevention has largely been overlooked as an issue important for sustainable development. Thankfully, there is now a global mandate for improving road safety. It is recognised as a major public health and sustainable development issue. Significantly, road injury prevention has been included in the United Nations (UN) 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) for ‘Good Health and Well-Being’ and ‘Sustainable Cities and Communities’ both refer to road safety and have specific targets for road injury prevention (targets 3.6 & 11.2).

More recently, a UN resolution[3] proclaimed the period 2021-2030 as a ‘Decade of Action for Road Safety’ and set a goal for countries to reduce road traffic deaths and injuries by at least 50 percent by the end of the decade. It also released a Global Plan for road safety[4] to guide countries on priority actions for implementation. With representatives of states and governments affirming their commitment to drive the implementation of the Global Plan at a high-level meeting of the UN General Assembly on Global Road Safety,[5] the challenge now is for countries to implement changes to achieve the target.

2. The G20’s Role

G20 countries account for 59 percent of global road traffic fatalities and include some of the world’s best and worst performing countries, with road safety performance differing significantly between high-income and low- and middle-income countries. With close to 800,000 people killed in road crashes (refer to Table 1) in G20 countries each year, the social and financial imperative for action is clear. The non-application of minimum safety standards for vehicles and roads contributes significantly to road trauma. Not only can road trauma lead to a loss of human life, it also causes heavy financial burdens as a result of life-changing injuries. This aspect of road trauma in G20 countries also warrants attention. It is projected that annual road trauma levels in G20 countries alone can reach more than 22,000,000 total deaths and injuries at an estimated cost of US$1.8 trillion.[6] An analysis of the status of G20 countries shows that many are still far from adopting best practices and that for every US$100 that road trauma costs, only US$1-3 is spent on prevention.

The G20 is in an ideal position to help change this rather grim picture of road safety as it stands right now by bringing attention to the issue and encouraging greater action to avoid road trauma. Leading countries have achieved ambitious road safety results with reductions in serious trauma by adopting a ‘Safe System’ approach that manages speed, improves road infrastructure and vehicles, while also supporting legislation, laws, enforcement, and medical care. Some countries are now aiming for zero road trauma by 2050. Many of the solutions to road trauma are known. However, lack of leadership, willingness to invest, and slowness to implement effective measures have had a detrimental effect on road safety. What is required is courageous leadership from within the G20 to implement proven road safety measures.

Table 1: Road safety status in G20 countries (6)

| Country | Estimated fatalities | Estimated rate per 100K population |

| Saudi Arabia | 9,311 | 28.8 |

| South Africa | 14,507 | 25.9 |

| India | 299,091 | 22.6 |

| Brazil | 41,007 | 19.7 |

| China | 256,180 | 18.2 |

| Russia | 25,969 | 18 |

| Argentina | 6,119 | 14 |

| Mexico | 16,725 | 13.1 |

| US | 39,888 | 12.4 |

| Turkey | 9,782 | 12.3 |

| Indonesia | 31,726 | 12.2 |

| South Korea | 4,990 | 9.8 |

| Canada | 2,118 | 5.8 |

| Australia | 1,351 | 5.6 |

| Italy | 3,333 | 5.6 |

| France | 3,585 | 5.5 |

| Germany | 3,327 | 4.1 |

| Japan | 5,224 | 4.1 |

| UK | 2,019 | 3.1 |

| EU (including France, Italy, and Germany) | 25,959 | 5.9 |

| Total | 791,966* |

Source: Global Status for Road Safety, 2018, World Health Organization (WHO)[7]

*Excludes double counting of fatalities in France, Italy and Germany which are also accounted for under the EU

The Safe System Approach to Road Safety

For road safety strategies to be effective, they need to be underpinned by a clear and strong vision, supported by a strong conceptual framework, and aided by responsible financing and associated performance monitoring. In recent years, the Safe System approach to road safety has been widely embraced as the most forward-thinking and effective way to achieve trauma reduction.

At the heart of the Safe System approach is the ethical imperative that one shouldn’t die or be seriously injured while using the road network. This approach reframes the road safety challenge by refraining from putting the blame on road users to considering how we can best protect all road users by designing, building, and managing a forgiving road system. The Safe System approach recognises that road users can make mistakes and our bodies are not designed to withstand the excessive forces of a road crash, exposing us to death and serious injuries. To mitigate these fundamental vulnerabilities of being human, the Safe System has the following guiding principles when addressing road trauma:

- People make mistakes that can lead to road crashes;

- The human body has a limited physical ability to tolerate crash forces before harm occurs;

- A shared responsibility exists among those who design, build, manage, and use roads and vehicles to provide post-crash care to prevent serious injury and death; and

- All parts of the system must be strengthened to multiply their effects; so even if one part fails, road users are still protected.[8]

According to the Safe System approach, road users cannot be expected to stay safe on the road by just following the rules, especially when the system they are operating within is inherently unsafe. Yet, many road safety policies place a heavy emphasis on improving road user behaviour, without concurrently investing in improving the aspects of the system that could change the inherent risks involved – vehicles and roads.

The importance of safer vehicles

Global research has shown that safe vehicles have immense potential for reducing road trauma by preventing crashes and protecting occupants. Safe vehicles are, therefore, one of the most viable road safety intervention available. Once vehicles are designed and manufactured based on a high safety standard and have utilised appropriate technologies, these safety benefits last the entire lifespan. of the vehicles. Given these benefits it is naturally very concerning that several countries have still not applied the minimum safety standards for vehicles recommended by the UN and its proposed Global Plan (see Table 2), and are continuing to allow poor-quality cars to be sold to the public.

Table 2: Priority UN vehicle safety standards

| Seatbelt Anchorages | UN Regulation 14 (R14) |

| Seatbelts | UN Regulation 16 (R16) |

| Child Seats | UN Regulation 44/129 (R44/129) |

| Motorcycle Anti-lock Braking System (MC ABS) | UN Regulation 78 (R78)/Global Technical Regulation 3 (GTR3) |

| Frontal Impact | UN Regulation 94 (R94) |

| Side Impact | UN Regulation 95 (R95) |

| Electronic Stability Control (ESC) | UN Regulation 140 (R140)/Global Technical Regulation 8 (GTR 8) |

| Pedestrian Protection | UN Regulation 127 (R127)/Global Technical Regulation 9 (GTR 9) |

| Autonomous Emergency Braking (AEB) | UN Regulation 150 (R150) |

| Intelligent Speed Assistance (ISA) | – |

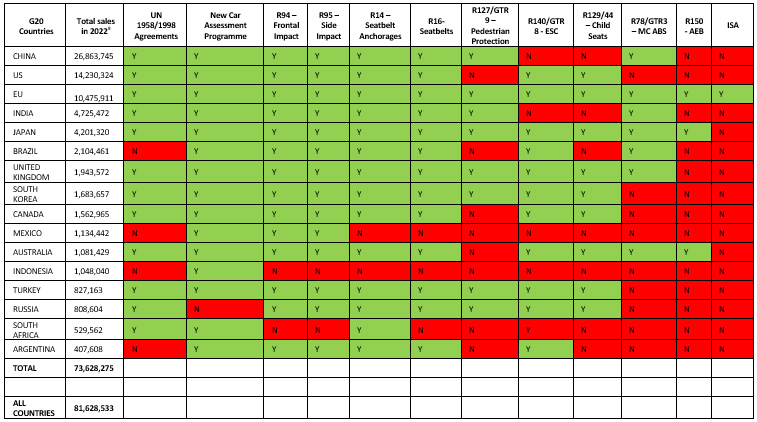

Alarmingly, many countries within the G20 have not fully applied the priority UN vehicle safety regulations. Without a universal adoption of the minimum safety standards, manufacturers are able to produce and sell sub-standard cars in countries that are yet to apply safety standards. Typically, these are low- and middle-income countries. It is, therefore, the need of the hour to make vehicle safety accessible globally through a uniform and universal application of minimum vehicle safety standards so that consumers can be empowered to buy affordable and safe cars.

Table 3: Status of priority UN vehicle safety regulations application in G20 countries

Every year, approximately 90 million new cars are produced and sold globally.[10] Of these, those that do not meet the minimum safety standards for vehicles will pose a threat to road safety in their lifespan and can be considered lost opportunities. Given the long lead time for the penetration of new technologies and a replacement of the existing vehicle fleet, there is an urgent need for swift implementation of appropriate legislations.

In 2017, the World Health Organization also facilitated the adoption of 12 voluntary global performance targets for road safety risk factors,[11] which were then welcomed by the UN General Assembly in April 2018.[12] These are intended to help member states guide action and measure progress during the implementation period in their advance towards meeting the SDGs by 2030. Together, they make up a global framework of safety performance indicators that could substantially reduce road deaths and serious injuries.

In this effort, the UN Global Road Safety Performance Target for vehicles is:

- Target 5 – By 2030, 100 percent of new (defined as produced, sold, or imported) and used vehicles meet high quality safety standards, such as the recommended priority UN Regulations, Global Technical Regulations, or equivalent recognised national performance requirements.[13]

The safety of the global fleet could be improved by meeting these targets, while also significantly reducing the number of people killed and seriously injured on the road. Implementing these standards in conjunction with consumer information partnerships like New Car Assessment Programmes could encourage the development of a market for safer vehicles locally and worldwide. The top ten car companies globally, accounting for 85 percent of global passenger car sales, are all based in G20 countries. These countries have the greatest ability to transform vehicle and environmental safety and the overall transport market.

The importance of safer roads

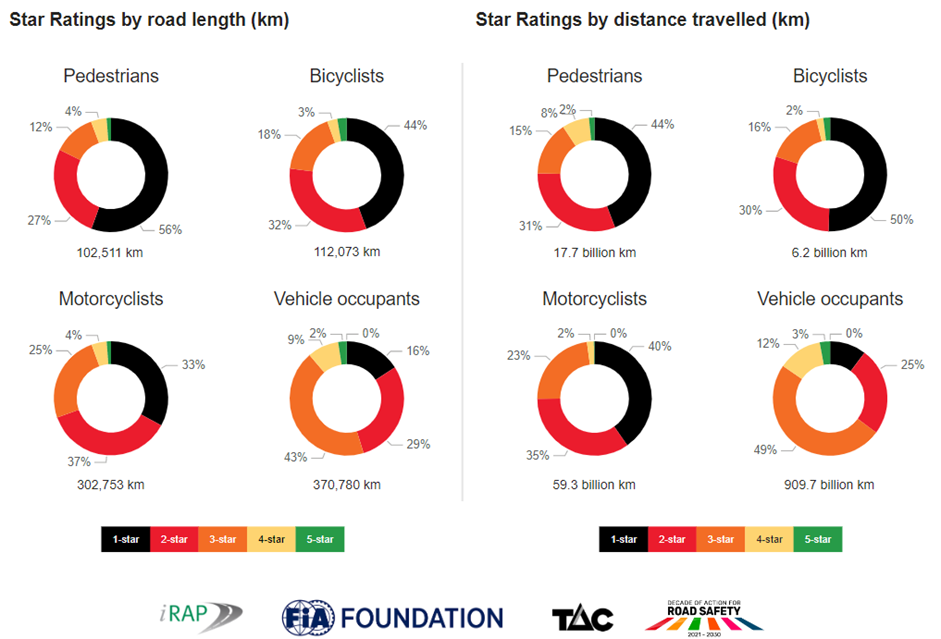

The impact of improved road infrastructure safety levels on road trauma outcomes cannot be overstated. When safety is prioritised during the planning, design, construction, and operation of roads, it can automatically reduce deaths and injuries. Yet, the quality of roads in G20 countries is still very poor, with 36 percent of vehicle travel being undertaken on 1 or 2-star roads (one star is the least safe, 5 star is the safest).[14] This is especially true for vulnerable road users who are even more susceptible to injury, with 75 percent of pedestrian travel, 80 percent of bicyclist travel, and 75 percent of motorcyclist travel being done on 1 or 2-star roads (Figure 1).[15]

Figure 1: Road Safety Star Ratings for a sample of roads in G20 countries**

Source: iRAP Safety Insights Explorer. iRAP[16]

**Sample of 369,000km of roads in 26 countries

- Target 3– By 2030, all new roads achieve technical standards for all road users that take into account road safety, or meet a three-star rating or better

- Target 4– By 2030, more than 75 percent of travel on existing roads is on roads that meet technical standards for all road users that take into account road safety (equivalent to a three-star rating or better)[17]

An estimated US$700 billion of road infrastructure investment is mobilised each year in G20 countries, with additional finance provided for road development and Overseas Development Assistance in emerging economies. The systematic application of the ‘3-star or better’ global standard for all road users as part of this existing investment arrangement represents a significant opportunity to deliver on both road safety and the climate agenda. The provision of safe infrastructure for pedestrians, cyclists, micro-mobility users, motorcyclists, and passenger and freight vehicles is fundamental to meeting many of the SDGs.

The benefits of the ‘3-star or better’ standard were demonstrated in the document G20 Principles for Quality Infrastructure Investment published during the Japanese presidency in 2019.[18] The OECD Safe System report also highlights the fact that crash costs per kilometre travelled are approximately halved for each incremental improvement in infrastructure star rating.6 iRAP estimates that there are US$14 of benefits for every $1 invested in reaching the global target of 75 percent of travel at the 3-star or better standard with an estimated 100 million deaths and serious injuries potentially saved globally over the life of the interventions deployed.[19]

A number of G20 countries are already focussing on policy targets and associated results-based investments. For example, the UK, Australia, India, Croatia, and Brazil have all included objective star rating targets at the national and/or project levels that meet or exceed these goals.

Historically though, these performance standards have not been in place and investment in roads has primarily focussed on providing access and capacity to private vehicles and increasing speeds. As a result, objective safety performance has often been overlooked as road networks have expanded, resulting in a large proportion of 1 and 2-star roads in G20 countries, with unacceptably high death and injury rates. This has an especially detrimental effect on child and adolescent health and well-being, with road crashes remaining the leading cause of death for young people.

The analysis for G20 countries indicates a return of US$6 for every US$1 of infrastructure investment that achieves the target of 75 percent of travel at a 3-star or better standard for all road users. An estimated 250,000 lives will be saved per year with more than 55 million people saved from death or serious injury over the life of the infrastructure interventions deployed.

In summation, with the Safe System approach to policymaking taking centre stage at the global, national, and local levels, the G20 can implement policies that will support investment in 3-star or better road infrastructures and ensure that the minimum UN regulations for all vehicles produced and used are implemented. While strategic implementation and priorities may differ between high income and low- and middle-income countries, safer vehicles and roads can help G20 countries meet the UN’s SDGs by 2030. Through public and private-sector results-based policy and financing the G20 can help save lives, save money, and create employment.

3. Recommendations to the G20

To help achieve the SDG goal for road traffic safety and to support the success of other SDGs, the G20 can consider the following policy interventions:

- Encouraging member countries to adopt the UN Global Road Safety Performance Target 5 for vehicles.

- Encouraging member countries to adopt UN Global Road Safety Performance Targets 3 and 4 for roads.

- Enabling member countries to develop and implement results-based financing mechanisms for safe and sustainable transport through national programs and overseas development assistance.

- Encouraging member countries to invest in road safety to advance adolescent health and well-being.

- Consider how the health benefits of improved road safety can be mobilised through the creation of road safety as an asset class for both private and public investments under the Sustainable Finance Working Group.

- Make road safety a priority issue, one to be addressed during Brazil’s G20 presidency in 2024.

Attribution: Jessica Truong et al., “Achieving the SDGs for Road Safety in G20 countries,” T20 Policy Brief, July 2023.

Endnotes

[1] World Health Organization, Global Status Report on Road Safety 2016, Geneva, WHO, 2018.

[2] WHO, Global Status Report on Road Safety 2016.

[3] “Seventy Fourth Session General Assembly Resolution: Improving Global Road Safety A/RES/74/299“, United Nations, accessed April 6, 2023.

[4] World Health Organization and United Nations Regional Commissions, Global Plan Decade of Action for Road Safety 2021–2030, Geneva: WHO, 2021.

[5] “Political Declaration of the High-Level Meeting on Improving Global Road Safety – The 2030 Horizon for Road Safety: Securing a Decade of Action and Delivery,” United Nations, accessed April 6, 2023.

[6] “iRAP Safety Insights Explorer,” International Road Assessment Program, accessed March 26, 2023.

[7] WHO, Global Status Report on Road Safety 2016.

[8] International Transport Forum, Zero Road Deaths and Serious Injuries: Leading a Paradigm Shift to a Safe System, (Paris: OECD Publishing, 2016).

[9] “Sales Statistics,” International Organisation of Motor Vehicle Manufacturers, accessed April 6, 2023.

[10] International Organisation of Motor Vehicle Manufacturers, “Sales Statistics.”

[11] “Global Road Safety Performance Targets,” World Health Organization, accessed April 6, 2023.

[12] “Seventy Second Session General Assembly Resolution: Improving Global Road Safety A/RES/72/271,” United Nations, accessed April 6, 2023.

[13] World Health Organization, “Global Road Safety Performance Targets.”

[14] “Are our roads 3-star or better?,” International Road Assessment Program, accessed April 6, 2023.

[15] International Road Assessment Program, “Are our roads 3-star or better? ”

[16] International Road Assessment Program, “iRAP Safety Insights Explorer”

[17] World Health Organization, “Global Road Safety Performance Targets”

[18] “Reference Guide on Output Specifications for Quality Infrastructure,” Global Infrastructure Hub, accessed February 8, 2023.

[19] International Road Assessment Program, “iRAP Safety Insights Explorer”

This is the latest available from WHO. The new report with updated data will be available in Nov/Dec 2023