Task Force 1: Macroeconomics, Trade, and Livelihoods: Policy Coherence and International Coordination

Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted global supply chains and highlighted the need for policy coordination to boost economic prosperity and well-being for all. Despite the inclusion of COVID-19 recovery and economic and social security in G20 action plans, significant developmental gaps preventing the equitable and affordable access to quality healthcare still need to be addressed among the grouping’s members. While COVID-19 has disrupted healthcare supply chains, balancing inclusive access to health and social services with sectoral modernisation is an ongoing challenge. In response to these challenges, this brief proposes three policy strategies: (i) promoting further trade liberalisation of health-related and social services, (ii) counterbalancing the adverse impacts of the liberalisation and deregulation of the sector, and (iii) enhancing supply chain resilience in the healthcare industry through depoliticisation and international cooperation.

The Challenge

The COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted global supply chains for both goods and services, particularly in healthcare systems. With many states imposing restrictions on the export of medical supplies during the pandemic, there has been a tumultuous effect on health systems in the Global South due to their higher dependence on such supplies. Vaccine shortages in the Global South highlight the need to build production capacity for domestic usage. Notably, other manufacturing nations opposed an effort by India and South Africa to diversify vaccine production in the Global South by proposing a waiver of the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS). This is an indication of the globalised world prioritising commercial interests over equitable development.

Unlike traditional supply chain systems, the healthcare supply chain employs sophisticated and comprehensive mechanisms. Due to the volatile geopolitical and geoeconomic climate, the supply chains developed based on political rationale may not account for economic rationales. Ensuring the systems’ independence from political imperatives with global implications, ranging from political divergences and conflicts to protectionist policies, is crucial to enhance their functioning. The imperatives of influences in near-shoring[a] and friend-shoring[b] have divided the world into two poles, wideningconomic and social gaps.[1] With developed economies preferring[2] alternate shores due to political divergences with traditional suppliers, orchestrating a newer supply chain has created an excessive burden on new suppliers breaching their capacity.

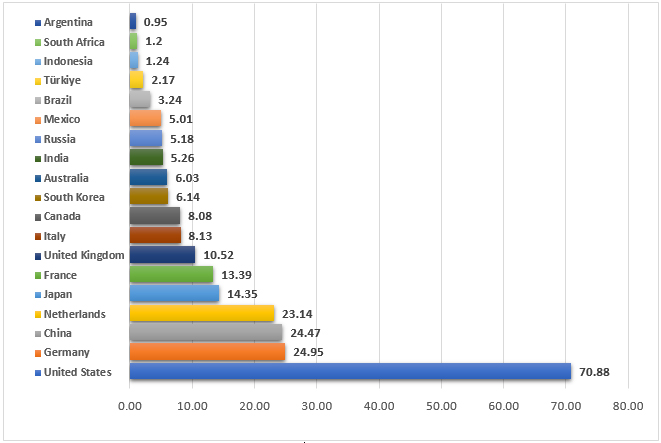

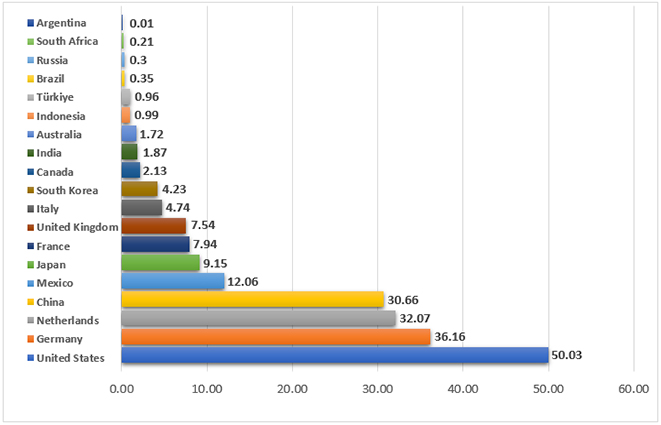

Figure 1 shows definite convergences among the G20 countries via healthcare trade data, i.e. pharmaceuticals and medical consumables to medical equipment and allied services. The advanced economies overshadow the Global South irrespective of scarcity in their health systems.[3] The polarisation of healthcare supply chains in North-North trade is evident.

Figure 1: Import and Export Data on Healthcare in 2021 (in US$ billions)

a. Import

b. Export

Source: Global Edge[4]

Simultaneously, varying levels of human development across the G20 cause unequal availability and accessibility to quality health-related and social services (HSS). Coordinated policy efforts and comprehensive strategies are required to eliminate such obstacles to human development. However, the lack of advanced technology, funding, human resources, and medical facilities, particularly in developing nations, hinders the implementation of such strategies.

Despite the effort to achieve Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 3.8[c] by 2030, no G20 country has achieved universal health coverage (UHC). Half of the G20 countries’ UHC Service Coverage Index (SCI) is less than 80, particularly those from emerging economies—India (61.2), Indonesia (58.7), and South Africa (67.5) (see Table 1).

Moreover, in response to the demographic challenge, trade liberalisation in the healthcare sector can improve policy balance in the advanced G20.[d] However, policymakers must consider the potential risks from the liberalisation and deregulation of HSS. Policymakers need help to divide resources between providing basic HSS and promoting the use of cutting-edge technologies in these services, i.e. balancing between (i) promoting equitable and affordable access to basic HSS, and (ii) modernising the HSS with recent technologies.[5]

Table 1: Key Indicators of Health-related and Social Services in the G20

| Population

(millions)

|

Population ages 65 and above (% of total population) | Current health expenditure (% of GDP) | Universal Health Coverage Service Coverage Index | Physicians (per 1,000 people) | Nurses and midwives (per 1,000 people) | Hospital beds (per 1,000 people) | ||||||

| 2021 | 2021 | 2019 | 2019 | 2020 | 2020 | 2019 | ||||||

| Argentina | 45.8 | 12 | Ageing | 9.51 | 73.4 | 4.1 | 2.6 | d | 5.0 | d | ||

| Australia | 25.7 | 17 | Aged | 9.91 | 87.2 | 4.1 | 13.1 | b | 3.8 | e | ||

| Brazil | 214.3 | 10 | Ageing | 9.59 | 75.0 | 2.3 | b | 7.4 | b | 2.1 | d | |

| Canada | 38.2 | 19 | Aged | 10.84 | 89.4 | 2.4 | b | 11.1 | 2.5 | |||

| China | 1,412.4 | 13 | Ageing | 5.35 | 82.2 | 2.2 | b | 3.1 | b | 4.3 | d | |

| France | 67.7 | 21 | Super-aged | 11.06 | 83.9 | 3.3 | b | 11.8 | b | 5.9 | c | |

| Germany | 83.2 | 22 | Super-aged | 11.70 | 85.8 | 4.4 | 14.2 | b | 8.0 | d | ||

| India | 1,407.6 | 7 | Ageing | 3.01 | 61.2 | 0.7 | 1.7 | 0.5 | d | |||

| Indonesia | 273.8 | 7 | Ageing | 2.90 | 58.7 | 0.6 | 4.0 | 1.0 | d | |||

| Italy | 59.1 | 24 | Super-aged | 8.67 | 83.4 | 3.9 | 6.3 | 3.1 | c | |||

| Japan | 125.7 | 30 | Super-aged | 10.74 | 84.9 | 2.5 | c | 11.9 | c | 13.0 | c | |

| Mexico | 126.7 | 8 | Ageing | 5.43 | 73.9 | 2.4 | b | 2.8 | b | 1.0 | c | |

| South Korea | 51.7 | 17 | Aged | 8.16 | 87.1 | 2.5 | b | 8.2 | b | 12.4 | c | |

| Russia | 143.4 | 16 | Aged | 5.65 | 75.4 | 3.8 | 8.5 | b | 7.1 | c | ||

| Saudi Arabia | 36.0 | 3 | Young | 5.69 | 72.9 | 2.7 | 5.8 | b | 2.2 | d | ||

| South Africa | 59.4 | 6 | Young | 9.11 | 67.5 | 0.8 | b | 5.0 | c | 2.3 | f | |

| Türkiye | 84.8 | 8 | Ageing | 4.34 | 78.7 | 1.9 | b | 3.0 | b | 2.9 | c | |

| UK | 67.3 | 19 | Aged | 10.15 | 87.7 | 3.0 | 8.9 | 2.5 | ||||

| US | 331.9 | 17 | Aged | 16.77 | 82.6 | 2.6 | c | 15.7 | c | 2.9 | d | |

| European Union | 447.2 | 21 | Super-aged | 9.92 | 79.2 | a | 3.9 | c | 9.5 | c | 4.6 | c |

Notes: a = Europe and Central Asia; b = 2019; c = 2018; d = 2017; e = 2016; f = 2010

Source: World Bank[6]

Table 2 shows the G20’s relatively low volumes and shares of HSS trade, implying the trivialisation of HSS significance in the ex-ante services trade liberalisation. In 2017, the G20’s HSS exports were US$25.8 billion, while the total imports were US$34 billion, accounting for only 0.5 percent of the total HSS trade values. The share of HSS trade becomes even smaller in the emerging G20, approximately ten times smaller than that of the advanced G20. The G20 economies experienced underutilised Mode 1 (supply through cross-border trade) and limited labour movement (Mode 4).[e] Despite facing similar challenges, the advanced and emerging G20 reveal different advantages in the HSS trade. The advanced G20 demonstrate their strength in Mode 3, showing the highest trade volume (US$27.0 billion of imports and US$22.2 billion of exports) and share (89 percent of imports and 93.9 percent of exports) among the HSS trade. However, the strength of the emerging G20 relies on Mode 2, with the largest import volume of US$2 billion (55.1 percent of the HHS trade) and export volume of US$1.8 billion (85.6 percent of the HSS trade). Thus, underutilised Mode 2 (consumption abroad) poses a challenge to the advanced G20, while difficulties in attracting foreign direct investment (Mode 3) pose a challenge to the emerging G20, shown via their lowest Mode 3 import volume (US$32 million or 1.5 percent of the emerging G20’s HSS trade).

Table 2. Estimated Value and Share of Health-related and Social Services Trade in the G20 (2017, in US$ millions and percent)

| Receipts from the world (imports) | Supply to the world (exports) | |||||||

| Health-related and

social services |

Total services | Health-related and

social services |

Total services | |||||

| G20 | Value | Share | Value | Share | Value | Share | Value | Share |

| Mode 1 ** | 925.5 | 2.7 | 1,994,703.2 | 26.8 | 522.2 | 2.0 | 1,521,417.3 | 28.2 |

| Mode 2 ** | 4,761.0 | 14.0 | 748,187.2 | 10.0 | 2,858.4 | 11.1 | 414,895.6 | 7.7 |

| Mode 3 ** | 27,970.5 | 82.3 | 4,509,635.9 | 60.6 | 22,203.7 | 86.2 | 3,272,680.9 | 60.6 |

| Mode 4 ** | 308.5 | 0.9 | 192,159.7 | 2.6 | 174.2 | 0.7 | 192,554.2 | 3.6 |

| Total | 33,965.4 | 100.0 | 7,444,686.0 | 100.0 | 25,758.4 | 100.0 | 5,401,548.0 | 100.0 |

| Advanced G20 * | Value | Share | Value | Share | Value | Share | Value | Share |

| Mode 1 | 434.0 | 1.4 | 1,391,720.1 | 26.1 | 314.7 | 1.3 | 1,067,639.4 | 27.0 |

| Mode 2 | 2,754.0 | 9.1 | 448,487.5 | 8.4 | 1,017.1 | 4.3 | 257,818.7 | 6.5 |

| Mode 3 | 26,987.6 | 89.0 | 3,346,753.0 | 62.8 | 22,171.7 | 93.9 | 2,492,696.9 | 63.1 |

| Mode 4 | 144.7 | 0.5 | 140,863.6 | 2.6 | 104.9 | 0.4 | 134,918.2 | 3.4 |

| Total | 30,320.3 | 100.0 | 5,327,824.2 | 100.0 | 23,608.3 | 100.0 | 3,953,073.3 | 100.0 |

| Emerging G20 * | Value | Share | Value | Share | Value | Share | Value | Share |

| Mode 1 | 491.5 | 13.5 | 602,983.0 | 28.5 | 207.5 | 9.7 | 453,777.9 | 31.3 |

| Mode 2 | 2,006.9 | 55.1 | 299,699.7 | 14.2 | 1,841.3 | 85.6 | 157,076.8 | 10.8 |

| Mode 3 | 982.8 | 27.0 | 1,162,882.9 | 54.9 | 32.0 | 1.5 | 779,984.0 | 53.8 |

| Mode 4 | 163.8 | 4.5 | 51,296.1 | 2.4 | 69.3 | 3.2 | 57,636.0 | 4.0 |

| Total | 3,645.2 | 100.0 | 2,116,861.8 | 100.0 | 2,150.1 | 100.0 | 1,448,474.7 | 100.0 |

Notes: for * refer to footnote d; for ** refer to footnote d

Source: World Trade Organization[7]

The G20’s Role

To ensure equal access to quality health, the G20’s roles should focus on (i) playing an intermediary role in ensuring the system’s independence from political outrages, and (ii) driving the commitment toward inclusiveness and resilience of the health system.

To eradicate the political interest-induced diversifications in the healthcare supply chain system, it is first necessary to apprehend the need for depoliticising, and to underline the international norms that declared the right to health a fundamental right[8].The G20 must comply with its commitment to long-term growth and sustainable development highlighted in the G20 Bali Leaders’ Declaration[9] through reformations to ensure resilient global supply chain networks and equitable multilateral trade. To achieve this vision, the G20 should warrant the system’s independence from political outrages and formulate actions to strengthen supply chains.

Second, the G20’s political will to achieve SDG 3.8 is critical. Continuity of the G20’s recommendations and interventions for ‘quality healthcare for all’ must be realised, while the purposeful commitment by the G20 governments should be reflected in policy actions translated into each jurisdiction’s regulatory and legal frameworks to facilitate health inclusiveness and resilience. To implement the following policy proposals, the G20 must explore various resources that help boost the healthcare industry toward UHC. This can be done by strengthening collaboration among the G20 members and between the G20 and the related international organisations (such as the World Trade Organization), and major multilateral development banks that can offer technical assistance programmes.

Recommendations to the G20

This policy brief proposes three main policy ideas to improve access to quality health for all.

-

Promote further ex-ante liberalisation of trade in health-related and social services (ex-ante liberalisation)

(1) Reforms with the implication of liberalisation

The G20 must undertake reforms customised to domestic characteristics in the HSS. Trade in HSS, based on comparative advantage through international cooperation, contributes to a sustained quality of services among the member countries. For instance, the advanced G20 may share more innovative clinical and medical services with the emerging G20, while the emerging economies can provide mid-skilled health workers to the advanced G20. Build-operate-transfer schemes by foreign players in constructing and managing HSS infrastructure are essential.[10] Such schemes require (i) financial reviewing for national basic healthcare systems and healthcare maintenance institutions, and (ii) establishing a monitoring, evaluation, and reporting system with up-to-date and more comprehensive HSS data, which is still lacking among the G20.[f] Periodical and disaggregated data collection and predictive analysis will improve the determination of capacities and demand for HSS, healthcare essentials, pharmaceuticals, and medical devices.

(2) Promoting public-private partnerships

Given government budget constraints, especially in the emerging G20, the comprehensive provision of HSS and quality improvement of universal healthcare warrants support from the advanced G20 and domestic and foreign investments through further trade liberalisation in healthcare goods and four modes of services.

The promotion of public-private partnerships in the Global South for healthcare products can help the emerging G20 to stipulate a cost-efficient model and modernise business strategies for healthcare supply chain management. The G20 can learn from the success of the Compact with Africa[g] in attracting foreign direct investments (FDI) and adopt a similar concept to boost healthcare investments in the emerging G20.

- Mode 1 – Raising domestic capacity in digital medical technology: Under the Indonesian and Indian G20 presidencies, digital health innovations were identified as key to health equity and sustainability. Emerging countries should allocate more public funding to research and develop digital medical technology in partnership with the private sector and the advanced G20.

- Mode 2 – Strengthening health-related and social services value chains among the advanced G20: The Health Working Group (HWG) under India’s presidency emphasises the significance of medical value travel (health or medical tourism) of the emerging G20 in eliminating healthcare disparities across regions. Leading global medical hubs established in Indonesia, India, and Mexico offer quality and cost-effective medical treatments and affordable social services, including foreign-specialised nursing or retirement homes. As the growing ageing population pushed the advanced G20 toward the burdens of rising expenditures of social security, pension systems, and healthcare,[11],[12] strengthening and leveraging HHS value chains among the G20 provides medical options to citizens, alleviating the fiscal burdens in the advanced G20 while improving income distribution among the emerging G20.

- Mode 3 – Reinforcing investment promotion policies and building investment ties with advanced economies: A mix of investment promotion policies will help attract FDI with medical innovation. Given the advanced G20’s strength, investment ties between the emerging G20 and the advanced G20 can be built by formulating a clear and transparent HSS policy and regulatory framework in the emerging G20. The focus should be quality assurance and removing the entry and operational restrictions on international branches of HSS businesses in the host countries. Moreover, the host countries can enable an investment environment for multinational enterprises (MNEs) and start-ups, such as promoting training programmes and relevant skill development.

- Mode 4 – Implementing the Mutual Recognition Agreements on the movement of natural persons in the health-related and social services sector: The underdeveloped Mutual Recognition Agreements (MRAs) in the HSS sector, including the poor documentation of cross-border natural person movement, the lack of accreditation and certification system, and language and communication barriers hamper the progress of the HSS trade in Mode 4. A lack of institutional capacity in the regulatory bodies among the G20 members, particularly in terms of funding and adequate legislative frameworks inhibits collaboration between professional organisations and relevant government entities.[13] Thus, the G20 must promote negotiations and coordination for the MRAs among the members based on international standards and regulations and health-related accreditation and certification to expand the HSS trade in this mode.

-

Counterbalance the negative impacts of the liberalisation and deregulation of health-related and social services (ex-post liberalisation)

- Quality assurance

The G20 must streamline institutional procedures, regulatory harmonisation, standardisation, and accreditation in HSS trade among the members for adequate quality assurance of healthcare workers and other HSS providers. Quality assurance not only guarantees UHC’s quality but also strengthens the ecosystem for MVT as emphasised by the HWG.

(2) Promoting universal health coverage for equal access to high-quality social and health services

The G20 must push forward the commitment toward UHC, including age-inclusive coverage, long-term care, national insurance coverage, and large-scale primary care[14]to counterbalance possible negative impacts of HSS-trade liberalisation. Furthermore, the G20 must determine the extent of private-sector engagement in healthcare provision. A clear and transparent HSS policy and regulatory framework derived from the sectoral consultation must be formulated to decide an optimal privatisation level that facilitates equal access to the services. Counterbalancing these factors in policy formation would promote the quality supply of and equality in HSS.

-

Enhance supply chain resilience in the healthcare industry through depoliticisation, trade liberalisation, and international cooperation

The depoliticisation of the healthcare supply chain can be achieved by strengthening the capabilities of the healthcare system in the Global South while expediting support from the advanced G20 and exploring technical assistances through international cooperation.

(1) Developing regional entities

Despite a massive scale of investment benefits delivered by its scheme, the G20 CwA gave rise to a market monopoly in the pharmaceutical sector among MNEs resulting in an absence of local manufacturers. Involving local manufacturers and non-governmental organisations in trade from end-to-end of the system and establishing regional entities will ensure a resilient supply chain and equal access in the emerging G20. Moreover, establishing state-owned enterprises and further liberalising trade in medical products can facilitate better resource allocation and utilisation by leveraging better regulatory implementations.

(2) Founding an incubation centre for capacity building on supply chain management

Replicating the Empretec, an incubation centre for developing countries with support from the advanced G20 and the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, can promote supply chain management and related trade knowledge to enhance the capacity of micro, small, and medium-sized enterprises in the global healthcare industry. The support can include advanced knowledge-sharing platforms, funding, and other assistance to entrepreneurs, particularly vulnerable groups.[15]

Attribution: Upalat Korwatanasakul et al., “Achieving Quality Health for All by Enhancing Healthcare Supply Chain Resilience and Trade Liberalisation,” T20 Policy Brief, May 2023.

[a] Near-shoring is the cross-border transfer of commercial operations or enterprises taking advantage of regional connectivity to ensure non-disrupted smooth supply and profitable trade.

[b] Friend-shoring is the practice of relocating supply chains and commercial operations to politically and economically friendly countries to extend their market access and avoid supply disruptions.

[c] SDG 3.8 aims to“achieve universal health coverage, including financial risk protection, access to quality essential health care services, and access to safe, effective, quality, and affordable essential medicines and vaccines for all.”

[d] The advanced G20 include Australia, Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the Republic of Korea, the UK, and the US, as well as the European Union, whereas the emerging G20 cover Argentina, Brazil, China, India, Indonesia, Mexico, Russia, Saudi Arabia, South Africa, and Türkiye.

[e] The four modes of trade in services are: Mode 1: Cross-border trade (telemedicine, including diagnostics and radiology); Mode 2: Consumption abroad (medical tourism, medically-assisted residence for retirees, foreign nationals seeking medical care in their nation of residence, and emergency situations, such as an accident while abroad); Mode 3: Commercial presence (foreign entities participating in or owning hospital/clinic or medical facilities, for example financial investments, technology alliances, and joint ventures); Mode 4: The movement of natural persons (medical professionals moving to work in commercial medical practice).

[f] The most updated data regarding key indicators of HSS in the G20 varies among the member countries from 2006 to 2021 (see Table 1), while the most updated HSS trade data is in 2017 (see Table 2).

[g] Compact with Africa (CwA) was introduced at the G20 in 2017 to promote investment and development in Africa through private-sector-led initiatives. The initiative is under collaboration with other international organisations and is deemed to improve investment conditions, increase employment, and foster sustainable growth in the region.

[1] Günther Maihold, “A New Geopolitics of Supply Chains: The Rise of Friend-Shoring,” SWP Comment 2022/C, no. 45 (July 2022): 2, doi:10.18449/2022C45.

[2] Juliette Rowsell, “What Happens When Politics Ensnares Supply Chains?,” Analysis, Supply Management, June 1, 2022.

[3] Lieve Fransen, John Nkengason, Smita Srinivas, and Stefano Vella. Boosting Equitable Access and Production of Diagnostics, Therapeutics and Vaccines to Confront Covid-19 on a Global Footing (Italy: Think20, 2021).

[4] GlobalEDGE. Healthcare: Trade Statistics, (March 16, 2023), distributed by Michigan State University.

[5] Upalat Korwatanasakul, Kaliappa Kalirajan, Hikari Ishido, and Martha Primanthi, Trade in Services: Health Related and Social Services (Promoting Services Trade in ASEAN: Second Phase (Social Services Paper 1) (Tokyo: ASEAN-Japan Centre, 2020).

[6] World Bank, World Bank Open Data, (March 16, 2023), distributed by the World Bank.

[7] World Trade Organization, Trade in Services data by mode of supply (TISMOS), (March 16, 2023), distributed by the World Trade Organization.

[8] Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, “Health Is a Fundamental Human Right,” Newsroom, World Health Organization, December 10, 2017.

[9] “G20 Bali Leaders’ Declaration,” G20, November 15-16, 2022.

[10] Fauziah Zen, “Capital Market Development and Financial Market Integration,” in Mid-Term Review of ASEAN Economic Community Blueprint, (Jakarta: Economic Research Institute for ASEAN and East Asia, 2012).

[11] Upalat Korwatanasakul, Pitchaya Sirivunnabood, and Adam Majoe, “Demographic Transition and its Impacts on Fiscal Sustainability in East and Southeast Asia” in Demographic Transition and Its Impacts in Asia and Europe, eds. Sang-Chul Park, Naohiro Ogawa, Chul-Ju Kim, Pitchaya Sirivunnabood, and Thai-Ha Le (Tokyo: Asian Development Bank Institute, 2021), 9-39.

[12] Pitchaya Sirivunnabood and Upalat Korwatanasakul, “Achieving Resilient and Inclusive Social Welfare Systems for Aging Societies against the Pandemic,” Think20 (T20): 1-2.

[13] Dovelyn Rannveig Mendoza and Guntur Sugiyarto, The Long Road Ahead: Status Report on the Implementation of the ASEAN Mutual Recognition Arrangements on Professional Services (Manila: Asian Development Bank, 2012).

[14] Pitchaya Sirivunnabood and Upalat Korwatanasakul, “Achieving Resilient and Inclusive Social Welfare Systems for Aging Societies against the Pandemic,” (Indonesia: Think20, 2022).

[15] “UNCTAD Empretec – Inspiring entrepreneurship,” United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, May 3, 2019.