Task Force 5: Purpose & Performance: Reassessing the Global Financial Order

Abstract

The global economy today faces a spectre of three expanding crises: huge burden of debt (public and private); repeated extreme weather events and other tragedies caused by climate change (which the world can now only adapt to, and not reduce); and the lingering public health and economic effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. These crises have become full-blown emergencies, particularly for the Least Developed Countries (LDCs). It is clear that concerted effort at the global level is required to address these challenges. Funding for such effort is in short supply as most developed economies have themselves accumulated huge debt burdens in recent years. This Policy Brief discusses international sources that could be used to provide the required financing and the resource mobilisation and disbursal mechanisms that could facilitate the effort.

1. The Challenge

Well before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic crisis, levels of debt (both public and private) were building up across the world. This was partly the consequence of the recovery effort from the Global Financial Crisis (2008-09) which had involved the massive provision of fiscal and monetary stimuli. Yet, in response to the low inflation during this period, interest rates were low and the debt appeared manageable. Beginning in 2020, however, the pandemic represented a dual public health and economic crisis, with each feeding on the other. Measures to control the pandemic (e.g. lockdowns) would exacerbate the economic crisis and permitting economic activity would lead to rapid spread of the novel coronavirus.[1] Policymakers the world over responded, at least in part, by providing massive fiscal and monetary stimuli. Much of the fiscal stimulus was debt-financed since the sharp downturn in economic activity reduced tax revenue. Depressed economic activity meant that interest rates could remain abnormally low. With the pandemic coming to an end, the built-up monetary and fiscal stimuli led to excessive liquidity in the economy and thus, high and sustained inflation. Sluggish supply conditions, largely the result of disruptions of global supply chains, meant that output could respond only with considerable lag to the rise in prices. Inflation targeting has meant that interest rates rose and are still rising sharply and the debt crisis is getting exacerbated.

Recent World Bank data[2] shows that external debt alone of low- and middle-income countries totalled US$ 9 trillion at the end of 2021. Rising interest rates increase the risk to global growth and induce debt distress. About 60 percent of the poorest countries are at high risk of debt distress or already in distress.[3] These countries therefore need urgent debt relief if they are to tide over the immense challenges thrown at them by the COVID-19 pandemic.

A second crucial demand on the global economy comes from the need to address climate change. It has become clear that avoiding or mitigating climate change is difficult now and adaptation is the only realistic option available for humanity. Such adaptation requires huge amounts of funds in the next few years to build the financial and technological capacity to combat perilous consequences of extreme weather events and other natural disasters as well as implications for soil productivity, among other impacts of climate change. Increased annual funding requirement aimed at helping vulnerable nations adapt to the climate emergency is estimated to be between US$160 billion and US$340 billion by the end of the decade, and up to US$565 billion by 2050.[4] The urgency of concerted and coordinated climate action is increasing over time and any further delays will only exacerbate the human and environmental cost of delayed and insufficient action.

Third, the COVID-19 pandemic has underscored the dire necessity of creating a separate fund to tackle issues of health security[5] to deal with the current COVID-19 pandemic crisis and prepare for the next one.[6] This would help prepare the world for pre-emptive action. There is heightened interest in creating a separate institution dedicated to health security, as a way of both addressing the current pandemic and preparing for the next disease outbreaks.[7]

Clearly, although all three challenges are pressing, they are not of equal importance nor do they have similar time dimensions. The debt challenge is most immediate and an endemic or pandemic challenge would become most pressing as and when it arises. The climate challenge is ongoing but more medium-term in nature for most countries. When resources are devoted to addressing these challenges, their nature and time dimensionality should be kept in mind.

2. The G20’s Role

The G20 can act as a galvanising force for addressing these key challenges. While several inputs would go into the design of policy responses, a critical one would be raising financial resources. This Policy Brief discusses possible sources of revenue to help ameliorate the difficulties mentioned above. It advocates the formation of a World Development Organisation (WDO) that would address the twin challenges of collecting and distributing this revenue. It also discusses some means to help address the challenges associated with the operations of the WDO.

The G20 as a grouping of the world’s 20 largest economies should take the initiative in this area. If it can make progress in addressing these issues, it will reveal itself as one of the most meaningful international organisations in the world.

3. Recommendations to the G20

In view of the debt crisis in many traditional donor countries,[8] international (supra-national) sources of development finance are urgently needed. Some literature discusses this point,[9] and a number of possible international sources of development finance have been suggested. Each of these policy measures has the additional advantage of correcting some external diseconomy. When opting for a particular set of financial resources, the revenue potential of these resources as well as the impact of such resource raising on external effects should be kept in mind. Twenty-one of these are noted in Table 1.

Table 1: Recent Suggestions for Global Revenue for International Development

| Measure | Comment |

| A tax on part or all of international financial transaction. This is often known as a Currency Transaction Tax (CTT). In some cases, a tax on bond turnover or derivatives is added. | Also called a ‘Tobin tax’ after the Nobel Prize winning economist James Tobin who first proposed it. |

| A variant of (1) cross-border capital tax. | Additional advantage: reducing excessive speculative capital flows. |

| Tax on fossil fuels or, more generally, a carbon tax. | Can discourage the use of fossil fuels. |

| Taxation of international arms trade. | By raising the price of armaments it could have the effect of discouraging international arms trade. |

| Surcharge on post and telecommunications revenue | The new price could better reflect the true social cost of these services. |

| A globally administered international lottery with the sale price going for international aid. | Depending on the size of the prize money and the frequency of the lottery, this could raise considerable amounts of revenue. |

| A surcharge on the highest income tax bracket within the country. | This would have the advantage of lowering inequalities both within and across countries. |

| Surcharges on domestic taxation of luxuries. | This would raise revenue by raising the price of luxury items. |

| Parking charges for international satellites. | This will have the additional advantage of pricing a global public good – i.e., outer space. |

| Royalties on minerals mined in international waters. | These minerals are currently being over-exploited because they have the characteristic of a “free good”. |

| A charge on the value of fishing/marine products caught in international waters. | This will have the additional advantage of reducing offtake of marine products from international waters. |

| Charges for exploration or exploitation of Antarctica. | Will reduce the over exploitation of a supposedly “free resource”. |

| Charges for the use of the electromagnetic spectrum. | Will reduce the over exploitation of a supposedly “free resource”. |

| A tax on aviation fuel. | Could help discourage the use of fossil fuels. |

| A tax on kerosene. | This has the advantage of discouraging the use of fossil fuels. |

| A tax or charge on international shipping and a charge for dumping at sea. | This would have the advantage of pricing the use of shipping lanes and of reducing ocean pollution. |

| A tax on traded pollution permits. | This has the advantage of discouraging the use of fossil fuels. |

| Voluntary taxes paid to a global agency | Will appeal to people’s altruistic motives. |

| A fresh stock of Special Drawing Rights (SDR) from the IMF distributed largely to LDCs. | This would increase liquid resources with the LDCs. |

| Sale of part of the IMF gold stock with the proceeds going to LDCs. | This would increase liquid resources with the LDCs. |

| A tax on the internet, social media usage and some other forms of communication. | This would raise considerable amounts of resources as these resources are in wide use. |

Source: Author’s compilation based on Jha (2004) and other sources.

A full but dated discussion of these potential sources of revenue is available in Atkinson (2004) and Jha (2004). This Policy Brief provides a summary discussion and update of the revenue potential of two such sources of revenue: the currency transaction tax and global carbon tax. Although all these policy measures could be tried, among others, the CTT and the carbon tax are perhaps most promising both in terms of revenue potential as well as amelioration of bad externalities. The most significant obstacle to pursuing these tax measures is the reluctance of many countries to cede some taxation authority to a supra-national body. In view of the pressing problems facing the world economy, it is for the G20 countries to initiate forward-looking policies that will serve the interests of global welfare.

The Currency Transaction Tax or the Tobin Tax would be imposed on all foreign currency transactions and other assets such as derivatives and T-bills. An EU document[10] estimates that a CTT of just 0.1 percent would raise over US$50 billion a year in revenue—even assuming that the number of current foreign exchange transactions fell by half, that 20 percent were exempt and that another 20 percent of the tax was evaded. This is more than double the total now spent on stabilisation programmes, development and humanitarian aid, peacekeeping operations and other activities by the United Nations (UN) and its agencies.[11] When Tobin originally proposed this tax he was largely interested in reducing volatility in financial markets “throwing sand in the wheels of finance” so as to reduce the impact of this volatility on speculation in the real world.[12] In the current context, it has the potential of being a major source of development finance. The pros and cons of a CTT have been extensively reviewed in the literature. There seems to be widespread support for this tax from a number of eminent economists including Nobel Laureates.[13] On the minus side, this tax would be disruptive of financial markets. However, it would have advantages in terms of revenue raised and lowering excessive speculation in financial markets.[14]

That carbon emissions have already created a climate emergency across the world is merely stating the obvious. Carbon taxation has now been adopted by several countries as a means of slowing down the global economy’s march towards higher temperatures and attendant problems. Two versions of the carbon tax have been discussed.[15] One is a so-called Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS), which caps the total level of greenhouse gas emissions and allows those industries with low emissions to sell their extra allowances to large emitters. By creating supply and demand for emission allowances, an ETS establishes a market price for greenhouse gas emissions. The second option is a global carbon tax whereby a price on carbon is directly set on greenhouse gas emissions or the carbon content of the fossil fuel. This is different from an ETS because with a carbon tax, the reduction in emissions is not pre-determined whereas with an ETS, it is. A country would choose one or the other depending on its circumstances. Revenue for international aid can only be collected from a global carbon tax. The global total carbon tax revenue potential is projected to be at US$ 436 billion by 2030.[16] Some of it could be used for international aid to LDCs.

G20 countries being the largest 20 economies in the world could have a significant role in the provision of such international aid to LDCs. This Policy Brief proposes that the G20 countries agree to form a WDO, whose primary purpose would be to collect revenue from one or more of the sources listed above (and others not listed in this brief, too). The express purpose is to provide funds to LDCs to help them meet the three critical exigencies that confront them. The setting up of the WDO would require agreement on several building blocks: (i) a mechanism for voting/taking decisions by the G-20 countries within the WDO has to be worked out; (ii) a formula for distribution of funds among LDCs needs to be devised; (iii) agreement on the split up of this aid between tied and untied aid would need to be reached; and (iv) arrangements for protecting the LDCs from some of the counter-effects of such large aid flows would need to devised.

A prior question to be addressed is why these revenues cannot be distributed by the World Bank or IMF and why a new institution needs to be created. The World Bank and IMF are operated by almost all nation states acting collectively through well-defined procedures. Their quota and voting structures are pre-determined and subject to periodic reviews. The WDO, on the other hand, would be operated by participating states and their modus operandi of engagement needs to be articulated. This would include, inter alia, the voting structure within the WDO and the disbursal of aid money so collected. All this needs to be done with a minimum of bureaucracy for efficient operation. At the very least, two elements would be necessary—a voting mechanism for decisions within the WDO, and a formula for distributing funds collected from international taxation.

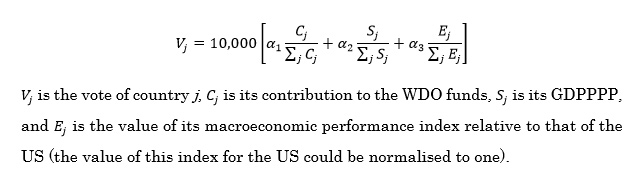

The votes for any country would be a critical determinant of its power to influence the operations of the WDO. Voting within the WDO would take place among the contributing G-20 countries.[17] This voting structure could have the following arguments: (i) amount of contribution to the WDO relative to total contribution; (ii) some measure of the size of the country – say its GDPPPP (GDP in PPP terms) or population; and (iii) rewarding of good macroeconomic management. Suppose the total votes within the WDO are 10,000. We distribute these votes among the members of the G20 countries as per:

For any particular year, this index is defined as the five-year moving average of macroeconomic performance consisting of (a) government deficit as a percentage of GDP; (b) current account (surplus or deficit) as a percentage of GDP; (c) inflation; and (d) rate of growth of real GDP per capita. Fiscal deficit, current account deficit and inflation are undesirables and could carry a negative value with equal weight for each. Growth of real per capita GDP is desirable and could be given a positive weight equal to the sum of the weights on government deficits, inflation and current account deficit. The weights are each positive fractions, their sum is equal to one and typically α1>α2>α3>. Details of the operation of the WDO can be worked out once it is set up.[18]

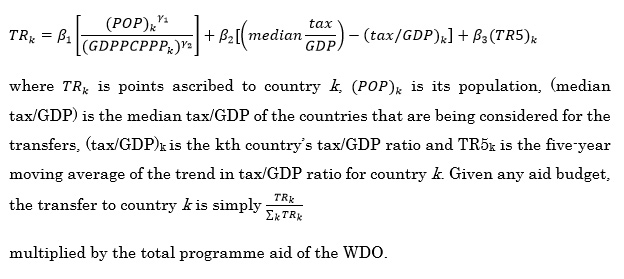

The disbursal of aid among the LDCs could take place according to a formula that determines the point ascribed to the particular LDC.

Disbursal of aid:

A third important consideration is the mix of tied and untied aid that would flow from the WDO. Most commentators have considered untied aid to be superior.[19] In any case, since the source of the funds would be international, tying of such aid would not be a serious point of contention. Nevertheless, some amount of tying should be considered to ensure that LDCs spend these funds largely on the three key areas mentioned above, i.e., (i) debt reduction and restructuring; (ii) climate change adaptation and mitigation policies; and (iii) public health preparations for combating current and future pandemics.

A final point to be considered is that the flow of such massive amounts of funds to LDCs could have ‘Dutch Disease’ effects on developing economies and lead to sharp appreciations in the currencies of the LDCs. A consequent slump in their exports, particularly manufacturing exports, is almost inevitable.[20] This could result in serious deindustrialisation of these countries. Therefore, corrective action to address these effects will be called for. Some economists have argued for keeping these funds in safe financial centres overseas and bringing them in only gradually[21] so as to moderate these Dutch Disease effects along with other judiciously chosen fiscal policy.

The current G20 President, India, with its impressive performance in the three areas of GDPPPP, macroeconomic stability and economic growth as well as in international institutions, is well-equipped to take the lead.[22] Prime Minister Narendra Modi has often emphasised the necessity of reorienting the G20 to the Global South.[23]

Attribution: Raghbendra Jha, “A Proposal for a World Development Organisation (WDO) to Address Emerging Global Economic Challenges,” T20 Policy Brief, May 2023.

(Author’s note: I am grateful to two anonymous reviewers for helpful comments on an earlier draft. The usual caveat applies.)

[1] Raghbendra Jha, Macroeconomics for Development: Prognosis and Prospects, (Cheltenham and Nottingham: Edward Elgar, 2023), 124-141.

[2] World Bank, “International Debt Report 2022,” accessed March 16, 2023.

[3] World Bank, “International Debt Report 2022”

[4] United Nations, “More funding needed for climate adaptation, as risks mount,” November 3, 2022.

[5] National Library of Medicine, “New Funds proposed to prevent pandemics,” July 16, 2020.

[6] Council on Foreign Relations, “1899-2023 Major Epidemics of the Modern Era,” accessed March 20, 2023.

[7] Garrett Wallace Brown et al., “Global Health Financing after COVID-19 and the new Pandemic Fund,” December 7, 2022.

[8] Trading Economics, “United States Gross Federal Debt to GDP,” March 17, 2023.

[9] Raghbendra Jha, “Innovative Sources of Development Finance: Global Cooperation in the 21st Century,” World Economy, 27, no.2 (February 2004): 193-214; Anthony, Atkinson, ed., New Sources of Development Finance. New York: Oxford University Press. 2004.

[10] European Parliament, “The Feasibility of an International ‘Tobin Tax’,” March 1999.

[11] Jha, “Innovative Sources of Development Finance: Global Cooperation in the 21st Century”

[12] Barry Eichengreen, James Tobin and Charles Wyplosz, “Two Cases for Sand in the Wheels of International Finance”. Economic Journal, 105, no.428 (January 1995):162-172.

[13] Paul Krugman, “Taxing the Speculators,” New York Times, November 27, 2009.

[14] Amy Youngblood Avitable, “Saving the World One Currency at a Time: Implementing the Tobin Tax,” Washington University Law Quarterly Review, 80, no.1, (January 2002): 391-417.

[15] World Bank, “Carbon Pricing,” accessed May 9, 2023.

[16] Shinichiro Fujimori, Tomoko Hasegawa and Ken Oshiro, “An assessment of the potential of using carbon tax revenue to tackle poverty,” Environmental Research Letters, 15, no. 114063, (Spring 2020): 1-8, DOI 10.1088/1748-9326/abb55d

[17] The following discussion follows some results in Raghbendra Jha (2004).

[18] The voting structure within the WDO would appear similar to those in the World Bank and IMF with one crucial difference- the World Bank and IMF are funded from contributions of member states, whereas revenue collected for the WDO would come from international activity and the voting formula should reflect the geographical origins of such resources. See: Raghbendra Jha and Mridul Saggar, “Towards a More Rational IMF Quota Structure Suggestions for the Creation of a New International Financial Architecture,” Development and Change, 31 no.3, (December 2002): 579-604.

[19] Arthur Johnson, Hirushi Muthukumarana and Anuk Kariyawasam, “Tied vs. Untied Aid: What is the best for of Foreign aid?” October 1, 2022.

[20] James Chen, “What is the Dutch Disease? Origins of Term and Examples,” October 31, 2021.

[21] Joseph Stiglitz, “We can now cure Dutch Disease,” Guardian, August 18, 2004.

[22] Australian Government Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, “The G-20,” accessed 21 March 2023.

[23] Sanjaya Baru, “India Can Still be a Bridge to the Global South,” accessed 21 March 2023, As G-20 President, India Can Still Be a Bridge to the Global South (foreignpolicy.com).