Task Force 4 Refuelling Growth: Clean Energy and Green Transitions

Abstract

The unrelenting impact of climate change poses an existential crisis for our planet. Immediate and substantial climate action to address this planetary crisis is only possible if the Global South and North countries partner together. To that end, the Global Climate Alliance (GCA) Collaborative[a] is an independent research effort to evaluate how the Global South can best ally with the Global North to accelerate climate action.

Over the past two years, several academic institutions and think tanks have collaborated on these issues. This effort has resulted in the outline of a framework for a GCA. The GCA initiative builds on existing climate agreements and multiple modelling studies that indicate that net zero is net positive. The overall goal of the GCA is to facilitate mutually-beneficial decarbonisation pathways between Global North and Global South countries jointly with necessary financial and technology partnerships. This policy brief discusses the key challenges in coordinating and accelerating ambitious climate action in the Global South, particularly the problem of scaling up private-sector climate finance. It also provides a brief description of the key principles for the proposed GCA, and discusses the major initiatives that can be undertaken by the G20 countries.

The brief also presents five actionable recommendations for the G20 Leader’s Summit: (1) announcing and endorsing the principles of a GCA as part of a dialogue with the G7 Climate Club process, aimed at creating a common structure that better reflects the interests of the Global South; (2) mobilising multilateral development banks to immediately launch novel climate financing mechanisms, such as long-term currency hedging; (3) establishing sectoral working groups that will formulate Paris-aligned decarbonisation targets, pathways, and financing requirements; (4) setting up a GCA secretariat under the aegis of the G20 as a bridging measure to help develop an integrated G20/G7 structure; and (5) designating nodal climate financing institutions in participating Global South countries to act as hubs to accelerate private sector climate financing.

The Challenge

-

The Climate Coordination Challenge

The 2015 Paris Agreement set an ambitious target of restricting the increase in average global temperatures to 2.0°C by 2100, preferably 1.5°C. Unfortunately, while countries have reiterated their decarbonisation targets, greenhouse gas emissions have continued to rise. Consequently, the United Nations Environment Programme is now projecting a significant rise in average global temperatures—2.8°C by the end of the century—under current policies.[1]

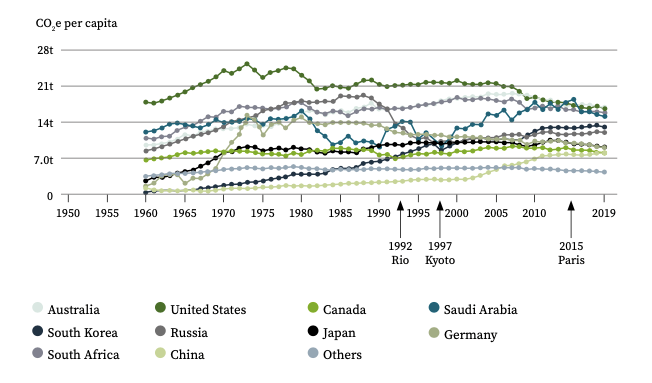

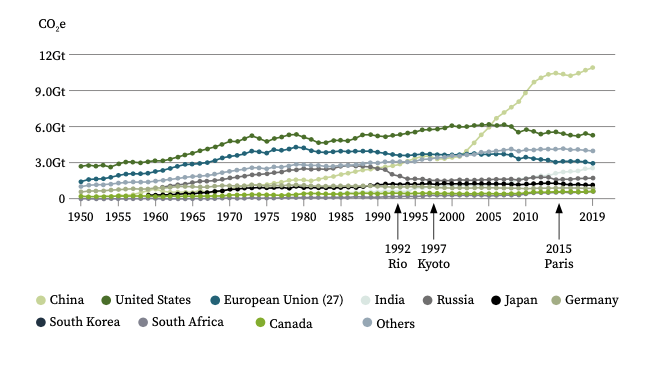

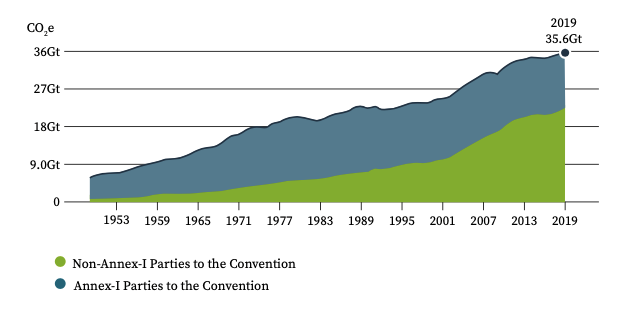

Coordinated global climate action is required to achieve the critical target of 2°C by 2100. To facilitate this, international organisations, such as the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), have been a forum for multiple climate discussions, resulting in the landmark agreements of Rio (1992), Kyoto (1997), and Paris (2015). However, emissions reductions in developed countries were negligible following Rio and Kyoto, and were negative in developing countries, which continued emitting. For developed countries, emissions reduction following Paris has marginally improved but remains slow. Figures 1, 2 and 3 that show the per capita and absolute CO2 emissions over the past seven decades clearly illustrates this point.

Figure 1: Historical Per-Capita CO2 Emissions

Source: Authors’ reconstruction[2]

Source: Authors reconstruction[3]

Source: Authors’ reconstruction[4]

-

The Climate Financing Challenge

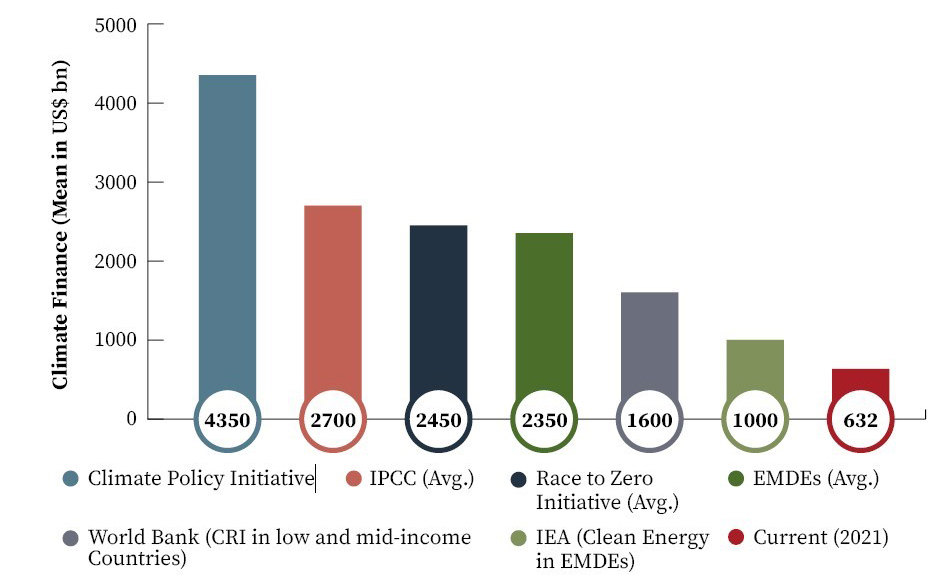

The Global South requires massive technological and financial resources to adapt to climate change and reach net zero by mid-century. As illustrated in Figure 4, several studies across private and public institutions have pegged these financial requirements in the range of trillions of dollars. This is in stark contrast to the US$100-billion pledge made in Paris.

At current levels, climate investments and climate finance in the Global South are thoroughly inadequate. They need to be dramatically scaled up to effectively tackle climate change. In 2021, the Global South invested only around US$380 billion in energy transition sectors. Of this, about 75 percent was in China, while Africa accounted for just 5.5 percent of global climate investments.[6] Moreover, the annual US$100-billion pledge by the Global North to support the Global South has not been met in any single year.

Figure 4: Climate Finance Requirements in 2030

Source: Compiled by the authors based on dataClimate Policy Initiative,[7] IPCC,[8] Race to Zero Initiative,[9] World Bank,[10] and IEA.[11]

Multilateral financial institutions such as IMF, the World Bank, and other multilateral development banks (MDBs) have not been able to bridge this vast financing gap in the Global South. Private sector capital mobilised by MDBs was around US$17 billion and US$31 billion in 2019 and 2020, respectively.[14] Further, the bulk of development finance revolves around public sector concessional loans. For example, private sector guarantees, and risk-management products represent only around 4 percent of the IFC’s total portfolio at US$475 million and US$40 million, respectively.

There is sufficient investible capital in the North to meet this large climate financing gap, housed in different institutional sources such as pension funds, sovereign wealth funds, and private insurance companies. But this money has not found its way to the South owing to numerous systemic risks. Some key risks pertinent to the Global South are currency risk, counter-party risk, and policy risk. These systemic risks are in addition to the usual business risks that investors must evaluate. Compounded by fragmented financial systems in the Global South countries, these risks make it almost impossible to mobilise trillions of dollars for climate finance.

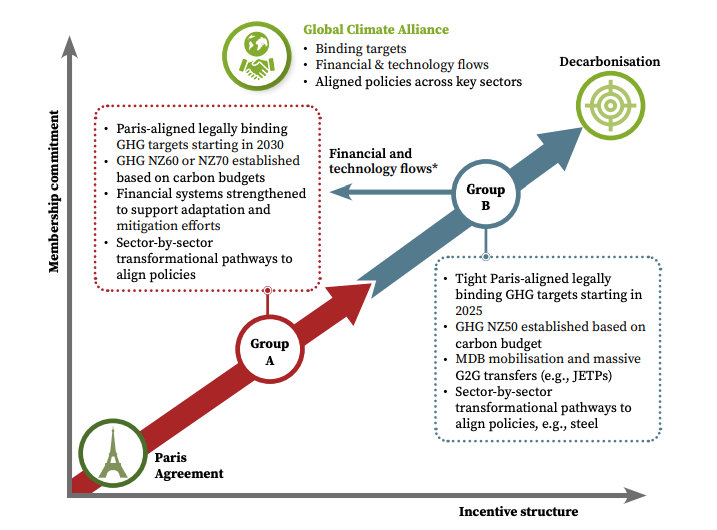

The G20’s Role in Accelerating Climate Action

The proposed Global Climate Alliance (GCA) aims to address these climate coordination and climate financing challenges by facilitating mutually-beneficial decarbonisation pathways between Global North and Global South countries jointly with the necessary financial and technology partnerships. Together, this partnership will dramatically accelerate climate action for resilience, adaptation, and mitigation measures (see Figure 5).

The proposed GCA comprises two groups. Group A members commit to following net zero pathways that lead to major greenhouse gas (GHG) emission reductions starting in 2030, and to net zero emissions by 2060 or 2070. Group B members commit to following net zero pathways that lead to quantifiable and transformative results in key sectors guided by a longer-term net zero target by 2045/2050. Following the CBDR principle, Global North countries are expected to join Group B and Global South countries to join Group A. However, all countries can pursue transformative action based on sectoral cooperation, and both member groups will obtain and provide mutual support for such transformative activities.

Figure 5: Proposed CBDR-Based Global Climate Alliance Framework

Note: Developing countries in Group B will also be entitled to financial flows as Group A developing countries/least-developed countries. NZ stands for net zero.

Source: Authors’ own

The GCA is guided by the following core principles:

- The GCA is primarily an economic programme to deliver on global investment and technology needs for inclusive and sustainable growth. It recognises that the overriding priority for the Global South is to improve living standards and achieve sustainable prosperity. Net zero is net positive for growth and development, particularly when compared to the damaging consequences of a rapidly warming world.

- The GCA must help unlock substantial amounts (‘trillions of dollars’) of public and private financing. It facilitates country platforms, enabling the tailoring of support to country-specific circumstances (for instance, JETPs), funding for industry transformation pathways, scaling up of MDB capacity, and improved regulatory infrastructure and de-risking tools for private finance. This recognises that both the volume and the cost of capital are critical constraints, while at the same time the capacity for budgetary forms of support post-COVID-19 is limited.

- The GCA will advocate lifestyle changes that India has articulated through Mission LiFE. The GCA will emphasise interventions intended to encourage responsible and sustainable consumption. Policy measures to encourage circular economy initiatives, reuse, and recycling will be developed.

- By participating in the GCA framework, the Global South gains access to substantially more climate finance for high-emission sectors. The GCA can deliver tangible outcomes within this decade—in terms of mitigation, investments, and jobs—in key industries such as renewables, steel, cement, and green hydrogen through:

- Joint development of transition pathways to climate neutrality for selected industries including decarbonisation compliance via sectoral working groups.

- Identification of financing and policy needs for private and public actors to realise such transitions at the national and regional levels.

- Cooperating on the implementation of suitable policies to prevent carbon leakage.

- Collaborative financing and support of selected green technologies for various industries.

Previous G20 presidencies and associated working groups have undertaken several high-impact initiatives to accelerate climate action, most notably in green financial regulations and MDB reform issues. A GCA that integrates these workstreams and develops an enduring partnership within the G20 framework will be an appropriate culmination of these efforts.

- Sustainable Finance Reporting and Disclosure Frameworks

The Green Finance Study Group was launched as early as in 2016 under the Chinese presidency. Its core mandate was “to identify institutional and market barriers to green finance.”[15] Under the German presidency, the industry-led Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures, established by the Financial Stability Board, outlined out its recommendations for voluntary disclosures of climate-related financial risks by corporates.[b]The Italian presidency in 2021 revamped the Sustainable Finance Study Group into a full-fledged working group with a clear roadmap. Around the same time the International Sustainability Standards Board was also launched to “develop a baseline global sustainability reporting standard while allowing flexibility for interoperability with national and regional requirements.” This group submitted its report to the Indonesian presidency.

- Private Climate Finance and MDB Reform

The Argentinian presidency clearly recognised the role of private capital in financing sustainability projects. It emphasised capital markets and developing sustainable private equity and venture capital sources. The Italian presidency urged the MDBs to “scale up their de-risking facilities for crowding in private sector finance.” The IMF also launched the SDR-rechannelling programme, a novel financial instrument, to scale financial transfers to developing and least developed countries. The G20 countries contributed around US$45 billion worth of SDRs. Currently, the Indian G20 presidency has constituted an expert group on Strengthening Multilateral Development Banks. Its two main objectives are creating a roadmap for the MDB ecosystem, and an evaluation of various financing estimates required to meet SDG and transboundary challenges.Additionally, the Energy Transition Working Group under the Sherpa track has continually dealt with energy transition issues associated with acquiring more sustainable sources of energy. The working group deliberates on energy security, accessibility and affordability, energy efficiency, renewable energy, innovation, technology, and financing in the energy sector.

Recommendations to the G20

The India G20 presidency could endorse the principles of the GCA. India can take several significant activities on this front over the next few months:

- Constructing and giving shape to the GCA;

- Playing a key role as the voice of the Global South in the climate club task force process initiated by the G7; and

- Crafting specific initiatives through the participation of experts, building a common structure (alliance/club) that reflects the interests of the Global South.

At the Delhi Leader’s Summit, the G20 can make the following key announcements:

- Global Climate Alliance for Accelerated Climate Action

The G20 Leader’s Summit could announce and endorse the principles of a GCA as part of a dialogue with the G7 Climate Club process aimed at creating a common structure that better reflects the interests of the Global South. The GCA would build on and support all existing global processes, such as G7, G20, COP, and UNFCCC. The declaration could be co-sponsored by the Indian presidency (representing lower-income and Asian countries) along with two other co-chairs (one representing OECD countries, and the other representing middle-income countries and South America).The co-chairs must set up the GCA’s governance, importantly the secretariat, that can take forward the principles of the alliance in an inclusive dialogue with the G7 task force aimed at creating common structures. To this end, the declaration must delineate the scope and objectives of such a common approach, espousing the goal of accelerated climate ambition through increased cooperation, improved coordination, and potential collective financing.

- Novel Financial Instruments to Accelerate Climate Finance

Along with the recommendations from the G20 Expert Group on MDB Reform, there are at least four financial products/structures that can be aggressively scaled up by MDBs to help reduce investment risks in transformational activities:

- Long-term currency hedging via currency swap lines;

- Credit guarantees via identified payment guarantee institutions;

- Climate insurance via a global risk pool; and

- Climate fund-of-funds to anchor venture capital funds.

- The Summit could immediately announce the launch of bilateral swap lines between central banks to protect climate investments from unexpected currency risk. Subsequent bilateral/multilateral deliberations or task forces could help set up a global risk pool and create a climate fund-of-funds.The GCA’s scope must include adaptation and loss and damage support. This will require binding annual commitments from the Global North. In any case, delivery of adaptation and loss and damage support will be through existing, agreed-upon mechanisms under the UNFCCC and other processes to ensure that no one is left behind.

- Sectoral Working Groups for Industrial Decarbonisation

Financial commitments from the Global North must be coupled with sectoral decarbonisation pathways in the Global South. While countries should chart their own transformation pathways, the focus will be on identifying sectoral targets for transformational activities for 2025 and 2030 and working sector-by-sector to achieve GHG neutrality. Decarbonisation initiatives in these targeted sectors serve as readily available avenues for investment flows.At the Summit, the G20 can set up sectoral working groups for charting decarbonisation pathways in specific industries/sectors. To complement the efforts of these working groups, the G20 could create an Industrial Decarbonisation Hub, on the lines of the Global Infrastructure Hub. The sectoral working groups must chart financial proposals to support these decarbonisation pathways. As an initial pilot, the GCA Collaborative had conducted a steel sector decarbonisation workshop, drawing in policymakers, associations, businesses, and analysts from the sector.[16]The SWGs must collaborate with a host of stakeholders, including businesses, governments, regulators, and civil society organisations among others. Countries can work on their sectors of choice—those where they can maximise emissions reductions, given their capabilities and commitments. Through these sectoral working groups, countries motivated to reach climate neutrality in their core sectors—for instance, steel, aluminium, cement, fertilisers and automotive—can cooperate closely, including aligning decarbonisation pathways.

- G20 GCA Secretariat

These early initiatives can be expedited through a GCA Secretariat under the aegis of the G20 as a bridging measure to help develop an integrated G20/G7 structure. The key functions of this secretariat will be to: help countries chart their decarbonisation pathways based on rigorous modelling studies and ensure their compliance; facilitate forums for aligning decarbonisation pathways of member countries along with support on capacity-building issues; and ensure compliance of financial commitments.

- Designated Local Green Investment Agencies

A key recommendation of the proposed GCA is the setting up of multiple Green Investment Agencies (GIAs) across Global South countries. These agencies will help identify green bankable projects and deploy blended finance. They will mobilise in-country financial expertise and engage diverse stakeholders within a climate transformation ecosystem. In addition, the GIAs can play a key role in sharing best practices, business models, and financing approaches.The Indian presidency could identify a GIA in India, which could then serve as a model for other Global South countries to emulate. The National Investment and Infrastructure Fund in India is a viable option to serve as a GIA.

Attribution: Jayant Sinha et al., “A Global Climate Alliance to Accelerate Climate Action: Proposals to the G20,” T20 Policy Brief, May 2023.

Endnotes

[a] The authors are part of the Global Climate Alliance Collaborative.

[b] A portion of the GCA Alliance design also borrows the TCFD’s principles and recommendations. For more, see GCA Collaborative, A Global Climate Alliance for Accelerated Climate Action, pp. 38-39.

[1] UNEP, Emissions Gap Report 2022: The Closing Window — Climate crisis calls for rapid transformation of societies, (Nairobi: United Nations Environment Programme, 2016).

[2] J. Gütschow, A. Günther, and M. Pflüger, The PRIMAP-hist national historical emissions time series v2.3.1 (1750-2019), (Zenodo, 2021).

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Scott Barrett, “Credible Commitments, Focal Points, and Tipping: The Strategy of Climate Treaty Design,” in Climate Change and Common Sense: Essays in Honour of Tom Schelling, eds. Robert W. Hahn and Alistair Ulph (New York: Oxford University Press, 2012), pp. 34-47. The chapter discusses the role of credible commitments under different climate treaties and why earlier Agreements failed to garner the right incentives.

[6] Analysis of data from BloombergNEF Portal.

[7] Climate Policy Initiative, Global Landscape of Climate Finance 2021, pp. 5.

[8] J. Rogelj et.al., “Mitigation Pathways Compatible with 1.5°C in the Context of Sustainable Development,” in Global Warming of 1.5°C. An IPCC Special Report on the impacts of global warming, eds. Masson-Delmotte et.al. (Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA: Cambridge University Press, 2018), pp. 93-17

[9] “What’s the cost of net zero?” Climate Champions, last modified November 3, 2021.

[10] Julie Rozenberg and Marianne Fay, Beyond the Gap : How Countries Can Afford the Infrastructure They Need while Protecting the Planet, (Washington, D.C.: World Bank Group, 2019). CRI stands for Critical Resilient Infrastructure.

[11] IEA, Net Zero by 2050: A Roadmap for the Global Energy Sector, (France: International Energy Agency, 2021).

[12] Current capex investment data sourced from Capitaline databases; GCA Collaborative, A Global Climate Alliance for Accelerated Climate Action, (New Delhi: Observer Research Foundation; Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung; German Institute for Economic Research (DIW Berlin), 2023), pp. 56.

[13] McKinsey & Company, Decarbonising India: Charting a pathway for sustainable growth, (McKinsey & Company, October 2022), pp. 114. Estimates are as per their accelerated decarbonisation scenario.

[14] Group of Multilateral Development Banks, Joint Report on Multilateral Development Banks’ Climate Finance, (London: European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, 2021).

[15] Communiqué, G20 Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors Meeting, 26-27 February 2016, Shanghai, China.

[16] GCA Collaborative, A Global Climate Alliance for Accelerated Climate Action, 2023, pp. 28.