Taskforce 6: Accelerating SDGs: Exploring New Pathways to the 2030 Agenda

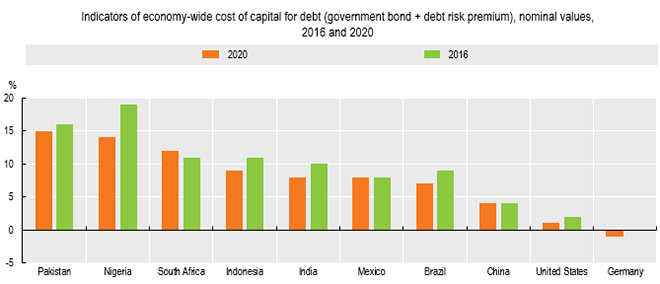

African countries suffer from higher costs of capital and the resulting constraints on governments’ abilities to respond to contracting global economic growth, major supply chain disruptions, and climate adaptation challenges. Schemes like official development assistance have left some countries with higher borrowing costs, leading to rapid increases in debt burden. As international asymmetries in development financing persist, and with the recent calls by African leaders for improved global governance rules, this policy brief considers changes in international cooperation and partnerships that could support Africa’s efforts towards building strong avenues to self-resiliency and sustainability. In this context, the brief will highlight practices in financing that can facilitate macroeconomic resilience in developing countries and offer some concrete proposals on: (i) modalities of international cooperation and partnerships that can strengthen Africa’s capacities to leverage existing financing tools; and (ii) the specific role the G20 could play in addressing global governance issues related to the reduction of the risk perception, the role of credit rating agencies, the rules related to exports credits, debt, and special drawing rights.

1. The Challenge

The global development and financing agenda has changed profoundly since the 2002 Monterrey Consensus.[1] The year 2015 was a key landmark in the evolution of the global framework for financing sustainable development, with the inking of the Addis Ababa Action Agenda (AAAA), the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), and the Paris Climate Agreement. During this evolution, traditional international cooperation mechanisms have coexisted with new ones, with the aim of adapting the financing to a multiplicity of global challenges and the rise of new actors, which increased due to COVID-19.[2]

Globally, the SDGs’ financing gap has widened from US$ 2.5 trillion to at least US$ 3.9 trillion per year since the outbreak of the pandemic, and is estimated to increase by US$ 400 billion per year between 2020 and 2025.[3] For Africa alone,[4] the annual financing gap for SDGs averaged US$$ 192.4 billion per year between 2020 and 2021, compared to US$ 200 billion in 2015. Such vast amounts of money cannot come solely from Official Development Assistance (ODA) or domestic public finance.[5],[6]

The adoption of the AAAA has led to many innovative financing instruments, such as the Integrated National Financing Frameworks (INFFs), the advancement of implementation guidance for the G20 Principles to Scale up Blended Finance, and the Addis Tax Initiative (ATI), which intended to support the domestic resource mobilisation (DRM) agenda in developing countries. However, the ambition to ensure adequate financing for sustainable development in the poorest and most vulnerable countries is still far from sight.

Developing countries are continuing to face multiples issues in accessing finance for ensuring sustainable development. Responses to the 2018 Global Outlook Survey on Financing for Sustainable Development by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)demonstrate that finance providers’ preferences rather than borrowers’ needs are still driving the choice of instrument in the financing market for sustainable development.[7] This is in addition to the inadequate or inexistent approaches for the increasing number of vulnerable middle-income countries. Moreover, the mechanics and channels for accessing support are at the centre of the debate on finance for development and existing asymmetries, impeding a more balanced and fair access to finance, and options for improving risks assessment are not considered enough. At least, three of these challenges are particularly pressing for most African countries.

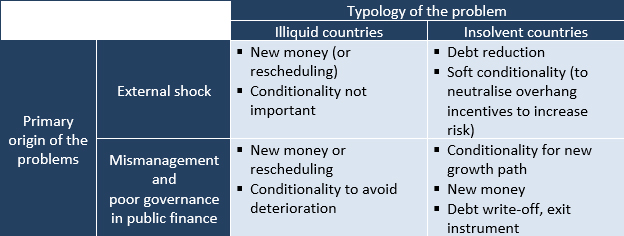

Challenge 1: Most African governments are confronted with limited fiscal space and insufficient access to international liquidity. Although debt-to-GDP ratios are still lower than before the heavily indebted poor countries (HIPC) initiative of the mid-1990s, the number of countries in debt stress is still significant and the trend is worrying. Average debt-to-GDP in African countries was 72 percent in 2020, but it was a lot higher in some middle-income countries such as Zambia (140 percent), Cabo Verde (158 percent) or Angola (136 percent). As of April 2023, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) considered eight African countries in debt distress (out of nine globally), plus 13 at a high risk of debt distress (out of 27 globally). Experts concur to say that Africa’s ongoing rising debt (see Figure 1) is a liquidity problem primarily due to multiple external shocks—from COVID-19 to the current rise in food prices and interest rates[8]. For example, Africa still needs up to US$ 130–170 billion annually to fill its infrastructure funding gap. Priority actions required are therefore quite different from those in 1990s debt crisis (see Table 1).

Despite some noticeable effort made, ongoing international initiatives have so far proved to be insufficient to address Africa’s needs for immediate liquidity. In an effort to support developing countries to cope with the Covid-19 pandemic financial burden, the G20 and the Paris Club launched a temporary Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI) in May 2020, which suspended US$ 12.9 billion in debt-service payments between May 2020 and December 2021 for 48 participating countries.[9] The total amount mobilised by the G20’s DSSI remains rather modest compared to the countries’ needs for liquidity, and only 48 out of 73 eligible countries participated in the initiative before it expired at the end of December 2021. Furthermore, progress on the other action plans so far is too weak to avert another possible major crisis:[10]

- The US$100 billion pledge in green finance has not been delivered. By 2020, climate finance reached only US$83.3 billion once counting all sources of funding—bilateral, multilateral, exports credit, and private.[11]

- The prospect of US$100 billion of Special Drawing Rights (SDRs) reallocation remains unfulfilled.[12]

- International financial institutes continue to lend at a business-as-usual rate, whereas Zambia, Ethiopia, and Chad have already been in a state of default for two years, without the G20-initiated Common Framework managing to find a resolution.

Figure 1. Evolution of Africa’s debt profile and level of public revenues over the past decades

Source: Authors’ own calculations based on the IMF’s World Economic Outlook Database and the World Bank’s International Debt Statistics Database.

Note: GNI – Gross National Income.

Table 1. Action required depending on typology and primary origin of debt problems

Source: Authors’ own analysis, adapted from Sokpoh, Kessler, and Floyd[13]

Figure 2. The cost of capital in clean energy projects in select countries

Source: International Energy Agency data.[17]

This is becoming a big issue for development because global shocks are more and more frequent. Broadly speaking, any global shocks on international markets (in terms of economic activity, financial flows, commodity prices, and the instability of the exchange rates of major currencies) automatically expose many developing countries to disproportionate transmission channels.

2. The G20’s Role

As countries face multiple overlapping crises, the amount of low-interest money available to countries should keep growing over the years to come. Despite the various efforts made, the world is far short of the amount needed to meet commitments to sustainable development and funding global public goods, including climate change and pandemic preparedness. Beyond that, we argue that efforts in international finance have been, so far, focused on the design of innovative financial tools and channels.

There is a strong need to refocus the discussion on developing countries’ needs for development finance and to consider a holistic approach, tackling asymmetries in the international financial architecture, finding options for reducing high risks perceptions in Africa, finding new providers of finance for development, and advancing the DRM agenda.

Risk mitigation tools to reduce the cost of capital

The conventional breakdown of financial products distinguishes loans, guarantees, and equity, but there are several possible variants on these, as well as scope to combine measures to meet the needs of both the funder and the final recipient.

Guarantees are the most straightforward financial product to design, implement, and recalibrate as economic development needs change. They have the most potential for impact where collateral-based lending is the norm, and the business ecosystem is not asset-rich. Leveraging a fraction of ODA to provide guarantee mechanisms for blended-project finance and currency hedging could catalyse more private investment for impactful sectors such as infrastructures and mezzanine finance for entrepreneurship.

- Investment in infrastructures is a case in point. Infrastructure-linked debts already account for a large share of commercial debt in Africa.[21] But Africa still needs some US$130-170 billion annually to bridge its infrastructure gap, and private funding for infrastructure development remains low: on average, the private sector committed only US$6.4 billion annually (7.5 percent of the total commitment for Africa’s infrastructure) between 2015 and 2018, compared to US$33.3 billion in East Asia.

- Similarly, guarantee mechanisms can unlock equity financing for Africa’s small and medium enterprises and talented entrepreneurs. The reach of guarantees can be significant when they are used as publicly- backed packages for start-ups and young firms.[22] In the digital economy, young and talented entrepreneurial Africans are combining digital technologies and their knowledge of regional markets to create fast-growing business models.

Since approximately US$30 billion per year of total ODA to Africa consists of pure grants, leveraging a small portion of this money through financial guarantees instruments can unleash much greater amount of additional financial resources for Africa’s infrastructure-related investment, and high-potential regional value-chain development. For instance, securitising just over US$ 5 billion would enable donor countries to raise US$100 billion of private capital funds for major infrastructure projects in Africa.[23]

Further changes to address current asymmetries in international financial architecture: Improving access to capital for developing countries

The first key point in the search for a better capital adequacy is the multilateral development banks (MDBs) reform agenda. Thanks to the G20’s active push since 2017, 2023 could be a landmark year for this specific aspect of the global Financing for Sustainable Development architecture reform agenda. The G20’s 2018 Global Financial Governance report has laid out the many ways in which such cooperation could be achieved.[24] In 2022, the G20 also commissioned an independent expert panel to review and propose an action plan to reform the MDBs’ Capital Adequacy Frameworks. If implemented, this action plan could collectively help to free up capital in the range of US$500 billion to US$1 trillion.[25]

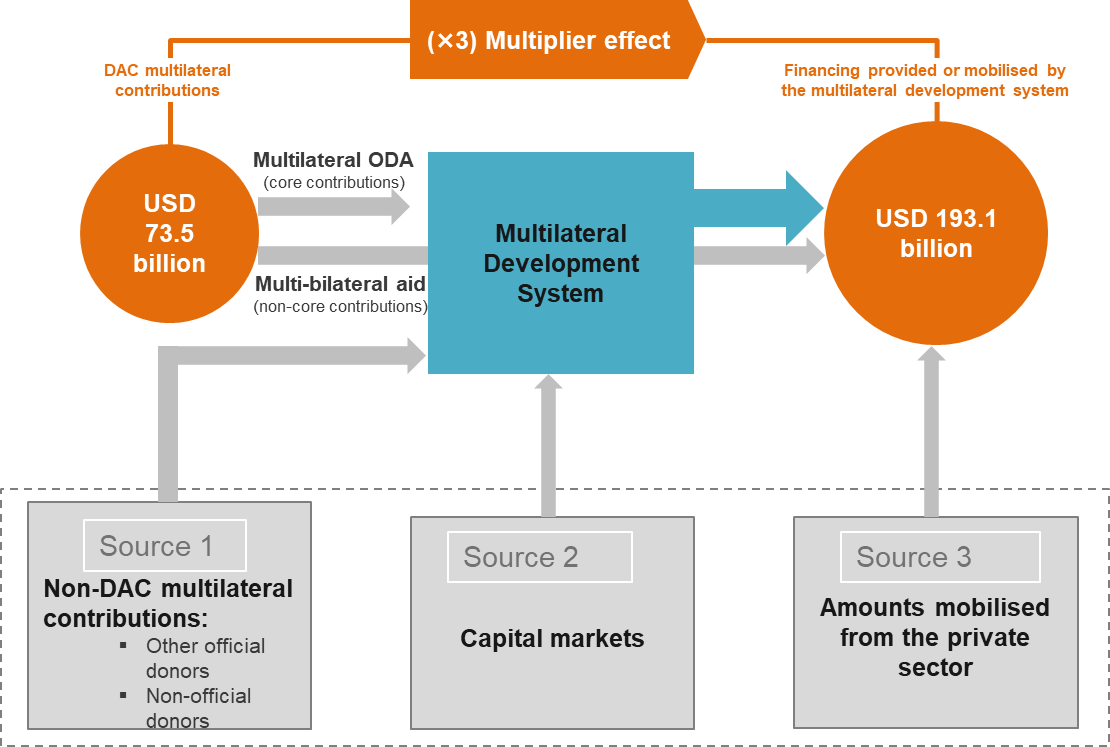

This MDBs reform agenda can make a difference in mobilising additional amounts for concessional financing through the MDBs’ capacity to leverage financing from multiple sources. The 2022 OECD report highlights that the volume of financing provided or mobilised by multilateral development organisations (US$193.1 billion on average between 2019 and 2020) far exceeded the volume of multilateral contributions provided by OECD Development Assistance Committee (DAC) members (US$73.5 billion over the same period).[26] This means that, each dollar of ODA channelled via the multilateral development organisations has delivered almost three dollars for sustainable development (see Figure 3). Under the proposed hybrid-capital framework for rechannelling SDRs, the African Development Bank’s lending capacity could also increase three to four times the number of SDRs invested, as compared to lending SDRs through the IMF at less than one-to-one value.[27]

Figure 3. The multilateral development system plays a significant multiplier role for DAC members’ multilateral contributions

Source: OECD data[28]

In the current international financial architecture, countries’ access to international concessional finance is heavily determined by their income category. For instance, access to concessional finance from the World Bank, as well as from several other multilateral financial institutions (the Asian Development Fund, the African Development Bank, the Asian Development Bank, and the IMF) is determined by the International Development Association eligibility thresholds, which are solely based on gross national income level – e.g. low- to middle-income statuses. Also, the OECD DAC’s list of ODA recipients is updated every three years, based on the income groups.[31]

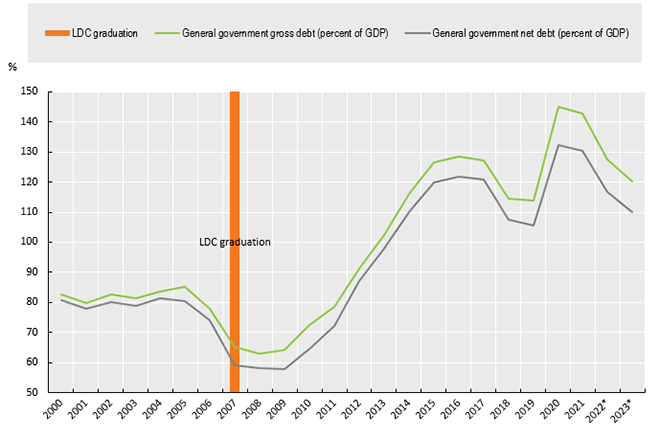

Accessibility of concessional finance based on the sole national income category is not the most appropriate. Average national income level does not fully reflect the real development of countries, since it does not take into account inequalities within the country, or other relevant dimensions of human well-being.[32] It is also ‘penalising’ countries that, by being graduated from ODA, saw that their traditional lines of communication were closing alongside the ODA programmes along with declining technical assistance and the learning and capacity development opportunities that accompany ODA projects and programmes.[33]Although graduation from the least developed countries (LDCs) status considers broader indicators than solely those related to the gross national income, the consequences are similar as those described above. For example, Cabo Verde’s[34] external debt steadily increased after its graduation from the LDC category in 2007 (see Figure 4); and for the first time in 2016, the country was classified by the IMF as being at “high risk” of debt distress.[35]

Figure 4. Government debt increased quickly after LDC graduation in Cabo Verde

Source: Author’s own elaboration based on data from the IMF World Economic Outlook Database and the World Economic Outlook Database, April 2023.

Notes: Estimates start after 2021

More support for countries to build capacities for additional resources mobilisation, including institutional investors

Direct budget support remains essential for governments in developing countries to improve DRM and public assets management and avoid the fiscal and credit crunch. Between 2015 and 2020, the OECD DAC members mobilised approximately US$ 310 million per year in ODA for DRM,[36] but still far from the target set by the ATI to double ODA to DRM in the period between 2015 and 2020 to US$ 441.1million.

In addition, the growing need for long-term financing calls for a growing role for domestic capital markets, including investment from the diaspora and institutional investors. To mobilise such resources, it is particularly crucial to produce more consistent, granular, and publicly available information on all types of investment opportunities, expected socio-economic impact, and financial returns, so that impact investors get timely information across countries. This would also have several advantages for the efficiency of public investment in general. First, public balance sheet management will be easier if quality data and the right methodology to assess the value of public asset are available. For instance, governments could easily use a broader variety of asset-class to improve their public finance management strategies. Second, countries with stronger balance sheets would enjoy lower borrowing costs[37] or benefits from new investment facilities. Some institutional investors are changing their modus operandi from an intermediary to a collaborative model. For instance, India’s National Investment and Infrastructure Fund (NIF) has been successful in mobilising capital from institutional investors.[38]

3. Recommendations to the G20

For risk mitigation tools

- The G20 countries can provide direct contribution or leverage a fraction of their SDRs as guarantee to mobilise additional resources for large continental projects. Such contributions can take the form of a ‘G20 Feasibility study fund’ or ‘G20 project preparation facility’ for the most transformative development projects. In the case of Africa, this support can be channelled through the Service Delivery Mechanism (SDM) of the African Union Development Agency ( and the related ‘5% Agenda’ campaign that aims to mobilise 5 percent of African private financial assets for African infrastructure projects development, up from its low base of approximately of 1.5 percent[39],[40]. Alternatively, G20 contributions can go through the AUDA-NEPAD Development Fund which is a flagship financing instrument aiming to expand resource mobilisation efforts through flexible fund models and innovative financing mechanisms for Africa’s most pressing priorities.

- Such facility can increase African countries’ access to risk mitigation guarantees and finance for infrastructure development through the AUDA-NEPAD which has several dedicated instruments. These include the African Infrastructure Guarantee Mechanism (AIGM) and Africa Co-Guarantee Platform (CGP). AUDA-NEPAD is allocated the critical role of leveraging the political will needed to improve enabling environments. These two instruments, if fully supported, will unlock specific projects: by providing access to a one-stop-shop of risk mitigation, AIGM and CGP can help unlock a wide spectrum of underutilised investment sources internationally and in Africa, such as Pension Funds (US$ 380 billion), Sovereign Wealth Funds (US$ 120 billion), and diaspora remittances (US$ 60 billion).

To improve access to capital for developing countries

- The G20 should continue to advocate for SDRs reallocation through multiple channels (it could be through those such as MDBs), because countries do not have the same needs. The 2021 allocation of SDRs by the IMF provided a vital lifeline for the global economy during the COVID-19 pandemic.[41] To speed up the process for putting the SDRs to use, it would be useful for the Indian or forthcoming South African G20 presidencies to launch a joint session of the development and finance working groups to rethink SDRs systems.

- In addition to the SDRs reallocation and the MDBs capital adequacy framework, the G20’s role should include institutional governance aspects. During the Senegalese Presidency of the African Union in 2022, President among others, had called for the African Union to have a permanent seat in the G20. This would be important to solve the lack of representation of Africa in key global decision-making institutions and processes. The India’s G20 presidency should strongly push for a more adequate representation of developing countries within the international financial institutions’ governance structure, and for their active role in regional financial arrangements.

- Access to development finance should be rethought beyond the national income, considering alternative indicators that better reflect the development of a country. Processes of ‘gradation’ from ODA might be discussed in the G20 context allowing for establishing smooth ODA graduation that would enable better adaptation to countries’ needs and challenges.

To support countries to build capacities for additional resources mobilisation

- The G20 should support the production of more granular and comparable data on non-financial public assets. The G20 should commission an expert panel group to elaborate a common definition and delineation of infrastructure assets in the national accounts’ framework. For instance, there is a strong need for international collaboration to exchange best practices on assumptions needed in the process (for example, life length of asset, depreciation pattern, and price developments).

- Another option would be to leverage part of the SDRs or ODA to set up a specific mechanism that will provide African countries with support to fast-track the development of Africa’s local currency bond markets. Local currency bonds would give countries a way to borrow that is protected from risks such as inflation, exchange rate shocks, or currency depreciations. Local currency bonds can also improve capital adequacy for the borrowers.

- Finally, the G20 can also mandate an international organisation to take stock of good practices and design a specific G20 facility for accelerating mobilisation of institutional investors for SDGs financing.

Attribution: Bakary Traoré, Rita Da Costa, and Daphine Muzawazi, “Rethinking International Cooperation and Partnerships for Improved Development Impact and Self-Sustainability in Africa,” T20 Policy Briefs, July 2023.

Endnotes

[a] UNDP summarises that “The research literature on credit ratings highlights several issues: a bias in favour of the home country of the ratings agencies or its economic allies, a bias against most forms of government intervention, a tendency for ratings to fluctuate with the business-cycle, and a conflict of interest (since the bond issuer pays the rating agency).”

[b] To recall the background: Between 2007 and 2020, 21 African countries took the opportunity to access foreign currency in international markets, many for the first time. The financial instrument used is commonly known as Eurobonds, although they can be denominated in US dollars or other currencies.

“The stock of African Eurobonds reached US$ 140 billion in 2021, having provided governments with a financial boost to their investment in infrastructure, technology, and skills” (Gregory Smith, “Africa’s hard-won market access”, in Finance & Development Special Feature: Africa at a Crossroads: Learning from the Past and Looking to the Future, December 2021).

[1] United Nation Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Monterrey Consensus of the International Conference on Financing for Development, Monterrey, Mexico, UN ECOSOC, March 18-22, 2002.

[2] Philippe Orliange and Ana Flávia Granja Barros-Platiau, “From Monterrey to Addis Ababa and Beyond,” Carta Internacional 15, no. 3 (November 2020): pp 5-28.

[3] Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Global Outlook on Financing for Sustainable Development 2023, Paris, OECD, November 10, 2022.

[4] African Union Commission and Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Africa’s Development Dynamics 2023: Investing in Sustainable Development, AUC and OECD, July 2023.

[5] United Nations Economic Commission for Africa, Long-term Financing for Sustainable Development in Africa, Economic Report on Africa, Addis Ababa, UNECA, 2020, pp 97-119.

[6] Thomas Mélonio, Jean-David Naudet, and Rémy Rioux, Official Development Assistance at the Age of Consequences, AFD Policy Paper, October 2022.

[7] Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Global Outlook on Financing for Sustainable Development 2019: Time to Face the Challenge (Summary), Paris, OECD, November 2018, pp1-2.

[8] AUC and OECD, Africa’s Development Dynamics 2023: Investing in Sustainable Development

[9] “Debt Service Suspension Initiative,” World Bank, March 10, 2022.

[10] Sokpoh Aurore, Ishac Diwan, and Martin Kessler, “The Development Finance Agenda Must Adapt to Africa’s Reality,” FinDevLab, November 24, 2022.

[11] Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Climate Finance and the US$ 100 Billion Goal, Paris, OECD, 2022.

[12] Barry Eichengreen and Poonam Gupta, “Priorities for the G20 Finance Track,” Working Paper No.: WP 145, National Growth and Macroeconomic Centre, February 2023.

[13] Aurore Sokpo, Martin Kessler, and Rob Floyd, “African Perspectives on the Current Debt Situation and Ways to Move Forward”, ACET, March 28, 2023.

[14] “The Cost of Capital in Clean Energy Transitions,” IEA, December 17, 2021.

[15] José Antonio Ocampo, “International Asymmetries and the Design of the International Financial System,” ECLAC, April 2001.

[16] United Nations Development Programme, “Lowering the Cost of Borrowing in Africa: The Role of Sovereign Credit Ratings”, UNDP Policy Brief, April 2023.

[17] IEA, “The Cost of Capital in Clean Energy Transitions”

[18] Ocampo, “International Asymmetries and the design of the international financial system”

[19] Ocampo, “International Asymmetries and the design of the international financial system”

[20] Daniela Gabor, “The Liquidity and Sustainability Facility for African Sovereign Bonds: Who Benefits?”, EURODAD, March 12, 2021.

[21] African Union Commission and Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Africa’s Development Dynamics 2021: Digital Transformation for Quality Jobs, Paris, AUC and OECD, January 2021.

[22] Fiona Wishlade and Rona Michie, “Financial Instruments in Practice: Uptake and Limitations,” Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development and European Commission, June 2017.

[23] Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala and Nancy Birdsall, “A Big Bond for Africa,” Project Syndicate, April 17, 2017.

[24] Global Financial Governance, “Making the Global Financial System Work for All: Report of the G20 Eminent Persons Group on Global Financial Governance,” Global Financial Governance, 2018.

[25] Independent Expert Panel convened by the G20, Boosting MDBs’ Investing Capacity: An Independent Review of Multilateral Development Banks’ Capital Adequacy Framework, Capital Adequacy Framework, G20, 2022.

[26] Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Multilateral Development Finance 2022, Paris, OECD, November 2022.

[27] Mark Plant, “Funding Hybrid Capital at the AfDB is the Best Deal for SDR Donors,” Centre for Global Development, March 9, 2023.

[28] OECD, Multilateral Development Finance 2022

[29] Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, How’s Life in Latin America? Measuring Well-being for Policy Making, Paris, OECD, October 2021.

[30] Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean and Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Emerging Challenges and Shifting Paradigms: New Perspectives on International Cooperation for Development, Santiago, ECLAC and OECD, September 2018.

[31] “DAC List of ODA Recipients,” Organisation for Economic Co-operation.

[32] “What is Development in Transition? A Blog Compilation,” OECD Development Matters, June 10, 2021.

[33] Rachel Calleja and Annalisa Prizzon, Moving Away from Aid: Lessons from Country Studies, London, Overseas Development Institute, December 2019.

[34] Cécilia Piemonte et al., “Transition Finance: Introduction a New Concept,” OECD Development Co-operation Working Papers, no. 54 (OECD Publishing, March 2019).

[35] ECLAC and OECD, Emerging Challenges and Shifting Paradigms

[36] OECD, Global Outlook on Financing for Sustainable Development 2023

[37] AUC and OECD, Africa’s Development Dynamics 2021

[38] Håvard Halland et al., “Mobilising Institutional Investor Capital for Climate-Aligned Development,” OECD Development Policy Papers, no. 35 (OECD Publishing, January 2021).

[39] “5% Agenda for an African Infrastructure Guarantee Scheme,” AUDA-NEPAD, October 4, 2018.

[40] Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development and African Center for Economic Transformation, Quality Infrastructure in 21st Century Africa: Prioritizing, Accelerating and Scaling up in the Context of Pida (2021-30), OECD and ACET, 2020.

[41] Kristalina Georgieva, “The Time Is Now: We Must Step Up Support For the Poorest Countries,” IMF Blogs, March 31, 2023.

[42] Nardos Bekele-Thomas, “In my view: Rethinking development to support Africa’s capacity and access to finance for development“, in Development Co-operation Report 2023: Debating the Aid System, Paris, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, February 2023.