Task Force 6: Accelerating SDGs: Exploring New Pathways to the 2030 Agenda

The G20 has for two decades played a leading role addressing risks and challenges to the global financial architecture and in innovating new structures in response. Today the world suffers from a series of interlinked crises. To address these challenges, this Policy Brief recommends that, at its India summit, the G20 leverage its track record of geo-economic leadership by taking concrete, initial steps to develop Global Public Investment: a new paradigm of international public finance that has the potential to meet 21st-century needs in climate, health, and other global, common challenges. Global Public Investment is a parallel arrangement to Official Development Assistance (ODA) in which all countries, not just donor countries, contribute and participate in priority setting and governance and in which all countries stand to benefit. This brief outlines how such a system could work and the G20’s potential role in initiating such an arrangement.

1. The Challenge

The world today confronts ever more complex international challenges—from climate adaptation to pandemic preparedness and social protection. Yet these challenges have, at present, no formal or coordinated financing arrangement to ensure that they are adequately addressed. The resulting undersupply of critical global public goods, leaves the world unprepared for the challenges of the current era, and the global commons under-protected. The narrow base of finance that is being made available via traditional means is not just wholly inadequate but also skews decision-making and priorities, as a small number of wealthy countries that contribute to global commons also demand a dominating influence over how this money is invested. Nor have private sector investments, efforts to “de-risk” private investments, or existing innovative finance mechanisms (such as the use of social impact bonds) proven effective or sufficient in financing basic and internationally agreed upon priorities.

Without an adequate mechanism to resolve them, these financing challenges often quickly become geopolitical flashpoints as well, with countries competing over the limited supply of global public goods on a highly uneven footing. This was apparent with respect to vaccine supply during the COVID-19 pandemic. It is apparent today with respect to the debt crisis that the pandemic has left in its wake (World Bank, 2022a and 2022b).

The economic gains of avoiding repeated crises by investing in essential commons and services is well-documented (McKinsey, 2021). Domestically, this is why citizens accept to pay taxes to their governments—to provide essential health systems, infrastructure, a social safety net, and public services.

Through the interconnectedness of the physical and economic worlds, these same needs now exist globally (Kaul et al., 2003, Reid-Henry 2015). However, there is so far no global public revenue structure or appropriate authority that can provide the investments and the compliance needed to meet the challenges that increasingly span national boundaries (Bird, 2014). In the absence of such a structure, governments of all income levels struggle to find ways of justifying expenditure on international agendas and affairs. OECD-DAC countries sometimes allocate some funds for global commons by drawing them away from already-pressed ODA budgets. Yet most countries do not have ODA budgets to draw upon, and even many high-income countries do not contribute to agreed international priorities, such as the Access to Covid-19 Tools Accelerator (ACT-A), because, for political or historical reasons, they do not see themselves as traditional “donor” countries.

At the same time, many middle-income countries in particular do have significant potential resources and interest to contribute to international public policy goals. However, they will not contemplate sizable contributions until they are part of a fair and representative governance structure.

The basic problem confronting rich and poor countries alike, therefore, is the absence of a commonly agreed financing arrangement in which all countries could contribute to the extent of their ability, and would get to decide over the uses of that funding. As a result, climate commitments, while agreed, are far from fulfilled, and the world remains unprepared for the next pandemic despite a consensus of “never again” in the aftermath of COVID-19.

In response to these challenges, influential voices have begun calling for a paradigm shift in financing global common needs (IMF, 2020; G7 Panel on Economic Resilience, 2021). Over the past 12 months, calls have been issued, among others by the G20 High-Level Independent Panel, on financing the Global Commons for Pandemic Preparedness and Response: “First, nations must commit to a new base of multilateral funding for global health security based on pre-agreed and equitable contribution shares by advanced and developing countries. We must recognize above all that international support for pandemic preparedness and response is fundamentally not about aid, but about investment in global public goods from which all nations benefit.” (G20 – High Level Panel on Financing the Global Commons for Pandemic Preparedness and Response). Yet, despite the urgency of these appeals, which extend beyond the global health sphere to encompass all the critical global public good arenas, and despite the huge economic costs for all countries of ignoring them, the international community has not been able to agree on an implementation plan.

2. The G20’s Role

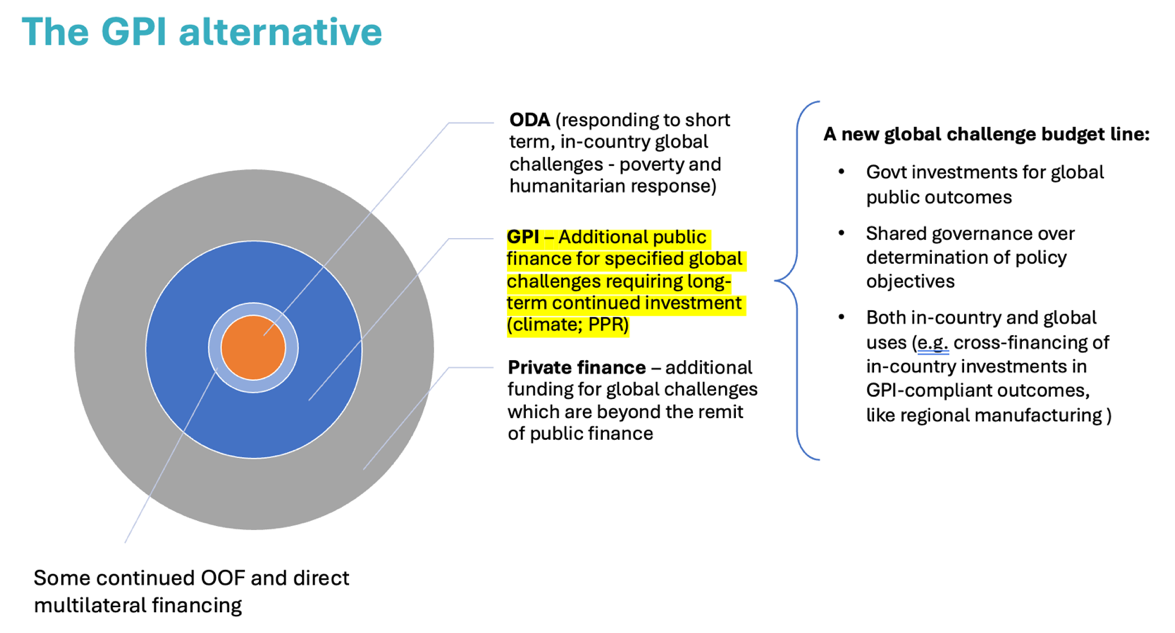

G20 nations have the capacity to address these challenges by pushing for the adoption of a new paradigm of international public finance—i.e., Global Public Investment (GPI) (Reid-Henry, 2019; Glennie, 2020). Global Public Investment calls for a “global challenges budget line” tied to a representative international governance structure overseeing priority-setting. The budget line would channel its funding through existing multilateral and government actors and agencies (including the World Bank system and multilateral development banks) as implanting entities. The Global Public Investment budget line could support both grant funding and concessional loan financing in expectation of a shared public return on those investments.

In a Global Public Investment arrangement, countries would come together to agree on global public policy priorities, with all contributing to those ends on a costed, fair, and ongoing basis, and with all having a say in how the money is allocated. By bringing more countries to the table as contributors and decision-makers alike, Global Public Investment could potentially raise more money than is presently secured for these purposes and in a way that is more resistant to geopolitical shocks. Through a fairer and more transparent governance structure, Global Public Investment could also ensure that countries are incentivised to actively participate in the resolution of global challenges, and that funds go to where they make the most difference, including marked “within country”, spent where appropriate.

How Global Public Investment Would Work

Global Public Investment builds upon the lessons on international financing that have emerged in recent decades, including South-South forms of cooperation; it also takes inspiration from long established practices of fiscal federalism (e.g. Boadway, 2003). In a Global Public Investment arrangement, funding would flow via dedicated agencies within the World Bank/Multilateral Development Bank (WB/MDB) system into appropriate national, regional and multilateral entities best placed to deliver on the policy objectives at hand. Global Public Investment thus proposes a radical evolution of the existing global financial architecture. GPI does not require a new, singular fund; rather its principles are meant to improve on existing funding mechanisms.

Embedding a Global Public Investment framework into the existing multilateral system would:

- Provide the necessary framework and mission-orientation to ensure that countries can meet their own share of the global needs that go under-supplied by the present ODA-dominated (and constrained) approach to international public finance.

- Fill a niche that today’s predominantly in-country lending cannot adequately meet, while raising substantial new and additional funding for cross-border challenges and market-shaping investments for public returns.

- Establish a new governance standard, answering years of calls for reform of the multilateral financial system so that itmore inclusively determined and allocated on the basis of unmet needs, which would incentivise a wider range of countries to participate.

- Leverage additional lending by more impactful banks, that can meet the growing global public needs more fairly.

- Better include middle-income countries in the global financial architecture.

These reforms would help establish four basic principles that define Global Public Investment as it extends the unique role of public money to the international arena:

- Universal Contributions. Global Public Investment shifts the burden from the current international structure of “donor” and “recipient” countries: instead, all countries contribute, according to their ability, and all countries are able to By expanding the geography of contributing countries, Global Public Investment can raise substantially more money.

- Ongoing Commitments. Global Public Investment moves us away from the idea that countries “graduate” after achieving a relatively low level of income per capita, as they do in ODA flows, or that three- to five-year replenishment windows represent the largest available planning windows. Global Public Investment would leverage ongoing but fractional commitments to investing in public returns, including in-kind domestic spending (Mazzucato and Donnelly, 2022). If the global community is to address today’s global challenges, countries must be able to plan for the longer

- Co-Responsibility. To ensure Universal Contributions (1) and Ongoing Commitments (2), Global Public Investment proposes a more democratic and accountable approach to the way that international public finance is Governance would not be weighted according to contribution (favouring rich countries) or by one-country-one-vote (favouring smaller, poorer countries and power blocs) but by a constituency system that gives all countries, including middle-income countries, a fair share in decision-making.

- Co-Creation. Global Public Investment moves from a one-size fits all financing arrangement to a more inclusive and devolved set of flows, where rich and poor countries co-design, consult and co-produce impactful solutions relevant to their needs locally as well as globally in dialogue also with civil society.

Immediate priority areas for a Global Public Investment arrangement would include (with others to be added as the mechanism evolves):

- Global Health needs, such as Pandemic Preparedness, Prevention and Response

- Climate Mitigation and Adaptation

- Disaster Risk Reduction

- Digital Transformation in health and other sectors

The difference Global Public Investment would make

To date, a great many reform proposals for the global financial architecture have struggled with what is elsewhere called the ‘participation trilemma’, which blocks different countries from cooperating effectively with one another.[a] Solving this trilemma requires countries themselves participating in the design of a Global Public Investment financing arrangement. This, in turn, requires a more coordinated arrangement, in which all countries share in the design and participate equitably in the prioritisation and production of global common needs. Such coordination would in many cases need to be regionalised, conforming to current geopolitical realities, while creating a platform for progressively enhanced global coordination over time.

In this arrangement, countries would determine overarching mission priorities, at a high level, with the technical and project-based work of implementation taking place through a combination of in-country spending, coordinating agencies, and implementing entities drawn from existing institutions within the global financial architecture, including existing issue-specific funds and parts of the WB/MDB architecture. This would enable a range of connected and resourced stakeholders to deliver on Global Public Investment by responding to programmatic proposals, impact analyses, and costings as required for mission prioritisation and objectives.

By doing so, Global Public Investment fills a gap between existing (narrow and fragmented) forms of international public finance, such as ODA, and often unrealised ambitions for larger quantities of private finance where public commitments and de-risking are prerequisites (Benn & Silborn, 2023).

Such a proposal would require the following institutional lifts:

- New principles. In the first instance, existing funds and multilateral agencies would need to adopt the principles of Global Public Investment and become Global Public Investment compliant.

- Internal systems would be required to enable project assessment, monitoring, working with mission-relevant coordinating partners (e.g. UN agencies) and financial intermediary funds (e.g. Global Fund, Green Climate Fund) as partners where appropriate.

- As investors, all countries would contribute a fair share of a defined and costed need over multi-year windows with equal voting, in a constituency arrangement, dependent on fulfilment of their contribution. They would need to be willing to work with approved coordinating and implementing partners in each mission area.

- New governance. Some parts of the global financial architecture (including some issue-specific funds and some of the multilateral development banks) are closer to a representative and globally legitimate decision-making structure than others, and the lessons of these entities should be built on as they evolve towards a Global Public Investment mandate.

- As members of decision-making constituencies overseeing Global Public Investment financing for prioritised mission areas, countries would be joined in such a Global Public Investment governance arrangement by Civil Society representatives (with votes) and would also receive technical advisory input.

- New investment lines. Such an approach would need countries to agree on high-level Global Public Investment mission financing objectives or prioritised “global challenges” where addressing these would involve either:

- National investments linked to regional/global strategies of sustainable development and that generate global externalities.

- Global investments linked to regional/global strategies of sustainable development and that generate national-level public returns.

The above ideas involve reforms rather than wholesale change of the current global financial architecture. Yet their effect would be to profoundly alter how the current system of international public finance operates (see Figure 1): making its governance radically more representative and enabling grant-based and market-shaping financing in priority issue areas that could, in turn, leverage much greater and coordinated public and private finance. Any fund or institution operating according to the principles of Global Public Investment could potentially be receiving and disbursing not only country contributions but eventually also pooled proceeds from international levies such as a financial transactions tax (a 0.1 percent tax on global transactions, at 2019 prices, would have raised US$237-418bn/yr).[b]

Figure 1. The GPI Alternative

Source: Authors’ own

3. Recommendations to the G20

The G20 should lead the development of a concrete and implementable framework for Global Public Investment, including considering how its core principles could be adopted within already existing multilateral funding settings. In doing so, it would be capitalising on its experience and legitimacy in fiscal governance and the fact that its membership includes leading economies across all regions.

The following specific actions are recommended:

- Provide leadership and ongoing commitment to a robust, crisis-resistant multilateralism.G20 members should commit to working as lead nations in the development and co-creation of Global Public Investment as a new paradigm in international public finance. Discussions within the G20 should connect to parallel high-level political processes (such as the United Nations Secretary General’s High-Level Panel on Effective Multilateralism, which also acknowledges the growing importance of a global public investment approach) and to current reform agendas addressing the WB/MDB system (such as the Bridgetown Agenda). It is the G20, however, which possesses the capacity to convene heads of state and finance ministers and the necessary experience in matters of fiscal governance to oversee the actual implementation of such a new approach to international public finance.

- Act as pathfinder for implementation of a Global Public Investment arrangement.Structural transformations, even ones considerably more modest than “Bretton Woods”-type moments, take time and careful negotiation to implement. The 2023 and 2024 G20 host nations should use their combined multilateral reach to take the lead in identifying domestic opportunities (e.g. NORAD, 2021) for how to implement a global challenges budget line, and to cooperate with global funds, the World Bank and the MDBs to explore modifications to governance and pay-out arrangements.

- Engage regionally for global solutions.The G20 should support initiatives within regional organisations (such as the Association of Southeast Asian Nations and the African Union), where G20 finance ministers are also engaged and that can contribute to the widespread acceptance of the principles of Global Public Investment, particularly with respect to establishing working regional solutions to the challenges of global fiscal governance.

Attribution: Simon Reid-Henry and Christoph Benn, “Global Public Investment for Global Challenges,” T20 Policy Brief, July 2023.

Bibliography

Bird, RM. “Global Taxes and International Taxation: Mirage and Reality.” Paper 31. Working Paper Series. International Center for Public Policy, 2014.

Boadway, Robin. “National Taxation, Fiscal Federalism, and Global Taxation.” Working Paper no. 2003/87. UNU-WIDER Discussion, December 2003.

G7 United Kingdom. “The Cornwall Consensus and Policy Recommendations.” G7 United Kingdom, 2021.

Ghatak, M., Jaravel, X., and Wiegel, J. “The World Has a $2.5 Trillion Problem. Here’s How to Solve It.” The New York Times, April 20, 2020.

Glennie, J. “The Future of Aid: Global Public Investment.” London: Routledge, November 30, 2020.

Henry, Reid-Simon. The Political Origins of Inequality: Why a more equal world is better for us all. University of Chicago Press, 2015.

Henry, Reid-Simon. “Global Public Investment: Redesigning International Public Finance for Social Cohesion – A Preliminary Sketch.” Revue d’économie du développement, Vol. 27/2 (2019): 169-201. DOI: 10.3917/edd.332.0169.

Johnson, Z., and Dwye, S. “Beyond ODA: Opportunities and challenges for new and additional funding for global health.” Donor Tracker Insights, February 25, 2022.

“Joint Statement: The Heads of the World Bank Group, IMF, WFP, and WTO Call for Urgent Coordinated Action on Food Security.” World Bank, April 13, 2022.

Kaul, I., Conceicao, P., Goulven, K.L., and Mendoza. “Providing Global Public Goods, Managing Globalization.” Published for the United Nations Development Project. Oxford University Press, 2003.

Kaul, I. “Enhancing the Provision of Global Public Goods: Ready for more realism?” UNDP Policy Brief, January 14, 2022.

Kuriansky, Judy, and Kakkattil, Pradeep (eds.). “Resilient Health: Leveraging Technology and Social Innovations to Transform Healthcare for COVID-19 Recovery and Beyond.” Elsevier, 2023.

Lakner, K., Özler, B., and Weide. “How would you distribute Covid-response funds to poor countries?” World Bank. Let’s Talk Development Blog, April 13, 2020.

Mazzucato, M., and Donnelly, A. “How do Design a Pandemic Preparedness and Response Fund.” Project Syndicate, April 20, 2022.

McKinsey & Company. “Not the Last Pandemic: investing now to reimagine public-health systems,” 2021.

NORAD. “Development Cooperation and Global Investments: What’s next for development cooperation.” Norwegian Church Aid. AID Under Pressure, October 2021.

Nordhau, W. “Climate Clubs: Overcoming free-riding in international climate policy.” American Economic Review, 2015: 1339–1370. http://dx.doi.org/10.1257/aer.15000001.

“Pandemic, Prices, and Poverty.” Data Blog. World Bank, April 13, 2022.

Thomas et al. “Reaffirming the significance of global public goods for health: Global solidarity in response to Covid-19 and future shocks.” Task Force 11. T20 Policy Brief, November 26, 2020.

Tooze, Adam. Shutdown: How Covid Shook the World’s Economy. London: Penguin, March 3, 2023.

United Nations. “Our Common Agenda: Report of the Secretary General.” New York: United Nations, 2021.

Weiser, Thomas. “Global Economic Resilience: Building Forward Better.” G7 Panel on Economic Resilience, October 14, 2021.

[a] Contra the binary assumption of “fiscal sovereignty”, the assumption that no nation will commit its resources to the disposition of others elsewhere, the “participation trilemma” identifies that countries at different income levels are locked into non-cooperation by a flawed system from which none can exit without penalty.

- Traditional donors increasingly want to share the burden of global fiscal allocation but do not want to give up the extensive influence they have accrued historically regarding how monies are spent.

- Non-traditional donors want greater rights to decide on global fiscal allocations but do not want to increase their contributions until such authority is granted.

- Beneficiary countries, who neither contribute nor have much voice in how the monies are allocated, cannot be brought to fully participate as decision-makers or contributors, and yet nor can they exit the system entirely.

From the point of view of multilateral cooperation each group faces a distinct problem of weak incentivization to cooperate and blocked exit to protest (in Hirschman’s terms). This trilemma locks the current system of under provision in place.

[b] Atanas Pekanov and Margit Schratzenstaller, “A Global Financial Transaction Tax: Theory, Practice, and Potential Revenue”, WIFO Working Paper No. 582 (May, 2019).